The Romneys’ Mexican History

Mitt Romney’s father was born in a small Mormon enclave where family members still live, surrounded by rugged beauty and violent drug cartels

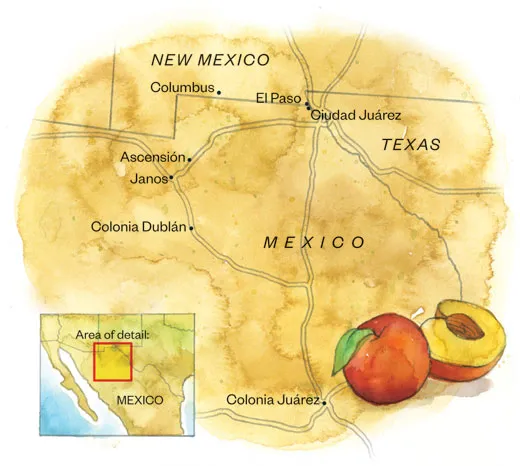

My journey to the Mormon heartland of Mexico began in a gloomy bar in Ciudad Juárez, just a short walk from the bridge over the Rio Grande and the U.S. border.

I ordered a margarita, a decidedly un-Mormon thing to do. But otherwise I was faithfully following in the footsteps of the pioneers of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, many of whom once passed through Ciudad Juárez on their way to build settlements in the remote mountains and foothills of northern Chihuahua.

Back in the late 19th century, the pioneers traveled by wagon or train. Neither conveyance is used much in northern Mexico these days. I arrived in El Paso from Los Angeles via airplane, and would travel by car from the border on a mission to see the Mormon colonies where Mitt Romney’s father, George, was born.

Mitt Romney, who is vying to be the next president of the United States, has family roots in Mexico. And not in just any part of Mexico, but in a place famous for producing true hombres, a rural frontier where thousands of Mormons still live, and where settling differences at the point of a gun has been a tragically resilient tradition.

These days northern Chihuahua is being ravaged by the so-called cartel drug wars, making Ciudad Juárez the most notoriously dangerous city in the Western Hemisphere. “Murder City,” the writer Charles Bowden called it in his most recent book.

I entered Ciudad Juárez just as a gorgeous canopy of lemon and tangerine twilight was settling over the border.

It isn’t advisable to travel through northern Chihuahua after dark, so I was going to have to spend a night in Ciudad Juárez before heading to the Mormon settlements, 170 miles to the south. Thus my visit to the Kentucky Club, where Frank Sinatra, Marilyn Monroe and assorted other stars downed cocktails.

“They say this is where the margarita was invented,” I told the bartender in Spanish.

“Así es,” he answered. I consider myself something of a margarita connoisseur, and this one was unremarkable. So was the bar’s wood décor. Honestly, there are two dozen Mexican-themed bars in Greater Los Angeles with better atmosphere.

Still, one has to give the watering hole credit just for staying open given the general sense of abandonment that has overtaken the old tourist haunts of Ciudad Juárez. Devout Mormons have always avoided the debauchery on offer there. Now everyone else does too.

On a Sunday night, the once vibrant commercial strips by the international bridges presented a forlorn sight. I saw sidewalks empty of pedestrian traffic leading to shuttered nightclubs and crumbling adobe buildings, all patrolled by the occasional squad of body-armored soldiers in pickup trucks toting charcoal-colored automatic weapons.

Beyond the border crossings, in the Ciudad Juárez of big malls and wide avenues, the city did not feel especially menacing to me—until I read the local newspapers, including El Diario: “Juárez Residents Reported Nearly 10 Carjackings a Day in January.” I spent the night in the Camino Real, a sleek example of modernist Mexican architecture, an echo of the Camino Real hotel in Mexico City designed by the late Ricardo Legorreta. I dined in eerily empty spaces, attended by teams of waiters with no one else to serve.

John Hatch, my guide to the Mormon colonies, arrived the next morning to pick me up. It was Hatch who had returned my phone call to the Mormon Temple in Colonia Juárez: He volunteers at the temple and also runs an outfit called Gavilán Tours. We were to drive three hours from Ciudad Juárez to Colonia Juárez, where Hatch and his wife, Sandra, run an informal bed-and-breakfast in their home, catering to a dwindling stream of tourists drawn to Chihuahua for its history and natural enchantments.

“I’m fourth generation in the colonies,” Hatch informed me. He can trace his roots to Mormon pioneers who traveled from Utah and Arizona to Mexico in 1890. He and Sandra have six children, all raised in the Mexican colonies and all now U.S. citizens, including one deployed with the Utah National Guard in Afghanistan. Hatch himself, however, has only Mexican citizenship.

His kids, he said, would rather live in Mexico but have been forced to live in the States for work. “No one wants to claim us,” he told me. “We feel enough of a tie to either country that we feel the right to criticize either one—and to get our dander up if we hear someone criticize either one.”

This state of feeling in between, I would soon learn, defines nearly every aspect of Mormon life in the old colonies. The settlers’ descendants, numbering several hundred in all, keep alive a culture that’s always been caught between Mexico and the United States, between the past and the present, between stability and crisis.

Hatch retired ten years ago after a long career as a teacher in Colonia Juárez at a private LDS academy where generations of Mexican Mormons in the colonies have learned in English. Among other subjects, he taught U.S. history. And as we left Ciudad Juárez behind, with a final, few scattered junkyards in our wake, he began to tell me about all the history embedded in the landscape surrounding us.

“See those mountains in the distance?” he asked as we sped past a sandy plain of dunes and mesquite shrubs. “That’s the Sierra Madre.” During the Mexican Revolution, Pancho Villa’s troops followed those hills, Hatch said, on their way to raid Columbus, New Mexico, in 1916.

Villa once rode and hid in those same mountains as a notorious local bandit. He became one of the revolution’s boldest generals, and attacked the United States as an act of vengeance for Woodrow Wilson’s support of his rival, Venustiano Carranza.

The Mexican Revolution played a critical role in the history of the Mormon colonies. Were it not for that 1910 uprising and the years of war that followed, Mitt Romney might have been born in Mexico, and might be living there today raising apples and peaches, as many of his cousins do.

An especially vicious faction of revolutionaries arrived in the colonies in 1912, appropriating the settlers’ cattle and looting their stores. The revolutionaries took one of the community’s leaders to a cottonwood tree outside Colonia Juárez and threatened to execute him if he didn’t deliver cash.

Many English-speaking families fled, never to return, including that of George Romney, then a boy of 5. In the States, George grew up primarily in the Salt Lake City area, attended college nearby, worked for Alcoa and became chairman of American Motors. He was elected governor of Michigan and served in President Richard Nixon’s cabinet. Mitt Romney’s mother, Utah-born Lenore LaFount Romney, was a former actress who ran unsuccessfully for U.S. Senate in Michigan in 1970.

As Hatch and I drove through Ascensión, one of the towns on the route to Colonia Juárez, he recounted the story of a hotel owner who was murdered there a few years back, and of a lynch mob that tracked down a band of three alleged kidnappers and killed them.

I’ll admit to being a bit freaked out hearing these stories: What am I doing here, in this modern-day Wild West? I wondered. But Hatch disabused me of my fears. Most of the worst violence in the region ended three years back, he told me. “We feel very blessed we have escaped the worst of it.”

Hatch would like to get the word out to his old U.S. clients who have been scared off. The Europeans, however, have kept coming, including a group from the Czech Republic that came to see local landmarks related to the history of Geronimo, the Apache fighter.

Geronimo’s wife, mother and three young children were killed by Mexican troops in a massacre in 1858, just outside the next village on our route, Janos. The enraged Geronimo then launched what would become a 30-year guerrilla campaign against the authorities on both sides of the border.

Finally, we arrived in one of the Mormon colonies, Colonia Dublán. I saw the house where George Romney was born in 1907. The old two-story, American colonial-style brick structure was sold by Romney family members in the early 1960s. Since remodeled, it now has a Mexican colonial-style stone facade.The maple-lined streets surrounding George Romney’s home were a picture of American small-town order circa 1900. There were many homes of brick and stone, some with the occasional Victorian flourish.

“This street is named for my first cousin,” Hatch told me, as we stood beneath a sign announcing “Calle Doctor Lothaire Bluth.” Hatch’s octogenarian uncle and aunt, Gayle and Ora Bluth, live on the same street. Ora was recently granted U.S. citizenship, but not Gayle, though he served on a U.S. Navy submarine (and represented Mexico in basketball at the 1960 Olympics in Rome).

It was a short drive to Colonia Juárez, where the Mormon colonies were founded and which remains the center of church life here. I first glimpsed the town as we descended a curving country road and entered a valley of orchards and swaying grasses. Even from a distance, Colonia Juárez presented an image of pastoral bliss and piety, its gleaming white temple rising from a small hill overlooking the town.

When the first settlers arrived here in the 1870s and ’80s, some were fleeing a U.S. crackdown on polygamy. (The practice ended after a 1904 LDS edict that polygamists would be excommunicated.) They dug canals to channel the flow of the Piedras Verdes River to their crops, though the river’s waters dropped precipitously low afterward. But lore has it that the Lord quickly provided: An earthquake triggered the return of an abundant flow.

There was no museum to which Hatch could direct me to learn this history, most of which I picked up from books written by the colonists’ descendants. Colonia Juárez isn’t really set up for large-scale tourism (in keeping with the Mormon ban on alcohol, it remains a dry town). Still, a stroll through the town is a pleasant experience.

I walked to the Academia Juárez, a stately brick edifice that wouldn’t look out of place on an Ivy League campus. On a gorgeous day of early spring, quiet filled the neighborhoods, and I could hear water flowing alongside most of the streets, inside three-foot-wide channels that irrigate peach and apple orchards and vegetable gardens amid small, well-kept brick homes.

Down in the center of town is the “swinging bridge,” a cable-and-plank span still used by pedestrians to cross the shallow Piedras Verdes. Hatch remembered bouncing on it as a boy.

“The old-timers said that if you had not been kissed on the swinging bridge, you’d never really been kissed,” he said.

This must be a great place to raise kids, I thought, a feeling that was confirmed later that evening when a local family invited me to a community potluck in the home of Lester Johnson. It was a Monday night, a time set aside, according to Mormon tradition, for family gatherings.

Before diving into assorted casseroles and enchilada dishes, we all bowed our heads in prayer. “We are grateful for the blessings we have,” Johnson said to the group, “and for the safety we enjoy.”

There was a toddler, and a woman of 90, and many teens, all of whom assembled in the living room later for the kind of relaxed, multigenerational neighborhood gathering that is all too rare on the other side of the border. They talked about family, school and other mundane or scary aspects of life in this part of Mexico, such as a local restaurant one of the moms stopped frequenting when she saw people with guns at another table.

But the bigger problem facing the English-speaking residents of the Mormon colonies is one common to rural life: keeping sons and daughters home when there isn’t enough work locally. Johnson, 57, has five children, all adopted, all Mexican. And all now live in the United States.

“We need to get some of our young people back here,” Johnson said. Like other members of the community, he said he resented the media coverage that draws ironic comparisons to the Republican Party’s hard-line position on immigration and the ambivalent feelings of Mitt’s bicultural Mexican cousins. “I don’t think anyone down here knows him personally,” Johnson said. Mitt Romney has reportedly not visited the area.

In Colonia Juárez, they might not know Mitt, but they do know the Romneys. Some see similarities between Mitt Romney, the public figure, and his Mexican relatives, some three dozen of whom are said to live in town.

Biographers of the Romney family have pointed to the “indomitable will” of the forebears. But this characteristic, it seems to me, is common to many of the Mormons of the colonies. Their shared determination is one of the things that has allowed a relatively small number of English-speaking people to keep their language and way of life essentially unchanged for more than a century, despite being surrounded by an often hostile Spanish-speaking culture.

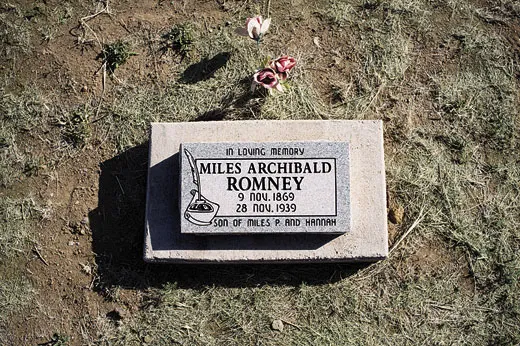

Leighton Romney, Mitt Romney’s second cousin, told me he hasn’t met the former governor of Massachusetts. (They have the same great-grandfather, Miles P. Romney, one of the 1885 pioneers.) I met Leighton the next day, on a visit to the fruit cooperative, packing house and export business he runs.

A 53-year-old dual citizen, Leighton has lived in Mexico all his life. Four of his uncles and one aunt served with the U.S. military in World War II. He knows the words to both country’s national anthems. Like people of Latin American descent living in the States, he hasn’t lost his sense of “kinship” to the country of his roots. “We’ve got a lot of similarities to Mexican-Americans,” he said. “We’re American-Mexicans.”

Leighton is deeply involved in the 2012 presidential campaign—the one to be held in Mexico in July to succeed outgoing President Felipe Calderon. Leighton is backing Enrique Peña Nieto, the candidate of the centrist Institutional Revolutionary Party, and is fundraising for him.

“We’re looking to have a little bit of a say in what the government here does,” Leighton said.

So the Mormon colonies will endure, I thought afterward, thanks to the industriousness and the adaptability of its residents. Like their ancestors, the pioneers still channel the waters of a river to their crops, still have big families and still learn the language and customs of the locals.

I spent my final hours in Mexico’s Mormon heartland playing tourist. I visited an old hacienda, abandoned by its owner during the revolution, and the ruins of the pre-Columbian mud city of Paquimé. I had the old walls and corridors of that ancient site all to myself and was soon enveloped by a soothing, natural quiet. In the distance, flocks of birds moved in flowing clouds over a strand of cottonwood trees.

In the town of Mata Ortiz, famous for its pottery, I was the only customer for the town beggar to bother. Here, too, were vast open vistas of cerulean sky and mud-colored mountains. Standing amid the town’s weather-beaten adobe homes and unpaved streets, I felt as if I had stepped back in time, to the lost epoch of the North American frontier: This, I thought, is what Santa Fe might have looked like a century ago.

Finally, John and Sandra Hatch gave me a ride back to the airport in El Paso. After crossing the border, we stopped in Columbus, New Mexico, where I received a final reminder of the violence that marks the history of this part of the globe. At a shop and informal museum inside the town’s old train depot, I saw a list of the people killed in Pancho Villa’s 1916 raid. Villa’s troops, a few hundred in all, were a ragtag bunch in cowhide sandals and rope belts. They killed eight soldiers and ten civilians, leading to Gen. John Pershing’s largely fruitless “Punitive Expedition” into Mexico days later.

I also saw an artifact from the more recent past: a newspaper clipping detailing the arrest, just last year, of the town’s mayor, police chief and others on charges of conspiring to smuggle guns to Mexican drug cartels.

We left Columbus down a lonely highway where we spotted more than a dozen U.S. Border Patrol vehicles and no other traffic. “Sometimes they follow us for miles,” Hatch said of the Border Patrol. Driving a big van with Chihuahua license plates seems to catch their attention.

Finally, we reached El Paso and I said goodbye to the Hatches, who gave me a parting gift—a copy of the Book of Mormon.

Photographer Eros Hoagland is based in Tijuana.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.