The Soul of Memphis

Despite setbacks, the Mississippi River city has held onto its rollicking blues joints, smokin’ barbecue and welcoming, can-do spirit

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/DA-Memphis-Beale-Street-Memphis-Tennessee-631.jpg)

Look up almost anywhere in downtown Memphis, and you might spot a small white birdhouse perched atop a tall metal pole—a chalet here, a pagoda there. The little aviaries add a touch of whimsy to a town that has known its share of trouble. “People like them,” says Henry Turley, the real estate developer who erected them. “I’m proud of those birdhouses.”

Turley built them because he has concentrated his business efforts on the older, westernmost part of his hometown, near the Mississippi River—where mosquitoes are thought to swarm. That’s no small matter in a city whose population was once devastated by yellow fever.

“People complained that it’s impossible to live near the river because it breeds mosquitoes,” Turley says in his elegant drawl. “So I put up the birdhouses to attract purple martins, which are supposed to eat thousands of mosquitoes on the wing. But mosquitoes don’t like flowing water. So it’s bullsh-t.” He savors this last word, even singing it slightly. “And it’s bullsh-t about the purple martins killing them,” he adds. “I’m fighting a myth with a myth.”

A man of sly humor and earthy charm, the silvery-haired Turley, 69, joins a long line of colorful characters in local lore—from Gen. Andrew Jackson, who co-founded Memphis in 1819 on what was then known as the fourth Chickasaw bluff, to E. H. “Boss” Crump, the machine politician who ran the city for a good half-century, to W. C. Handy, B.B. King, Elvis Presley and a disproportionate number of other influential and beloved musicians. Turley is a sixth-generation Memphian descended from one of the Bluff City’s earliest white settlers; his great-grandfather was a Confederate rifleman who later served in the U.S. Senate. Birdhouses aside, Henry Turley’s stellar local reputation has more to do with what happened after the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated here in 1968.

That traumatic event and the ensuing riots accelerated an inner-city decay that fed on racial disharmony, tax-advantaged suburban development and the decline of Memphis’ economic mainstays—especially King Cotton. Businesses and homeowners gravitated toward suburban havens to the east, such as Germantown and Collierville. But a hardy few, notably Turley and his oft-times partner Jack Belz, stood firm. And thanks to them and a few others, the city’s heart has steadily regained its beat. Several Turley-Belz developments have earned acclaim, such as Harbor Town, the New Urbanist community on Mud Island, and South Bluffs, a cobblestoned enclave overlooking the Mississippi near the old Lorraine Motel, where King was shot. But closest to Turley’s heart is a project called Uptown, which he undertook with Belz and the city government in 2002. They’ve built or renovated some 1,000 homes, fostered small businesses and carved out green spaces throughout a 100-block section that Turley says was probably the most degraded part of the city. And the new houses don’t all look alike. “We’re trying to make a nice neighborhood to live in, even if you happen to be poor,” he says.

Turley denies that he has any grand visions as an urbanist. He’s more like a blues guitarist who builds a solo gradually, from one chorus to the next. “We set out in a sort of dreamy Memphis way,” he says. “And remember, Memphis has a lot of freedom, Memphis is a place of creativity. I mean a pretty profound freedom, where there aren’t so many social pressures to behave a certain way. In Memphis you can do any goddamned crazy thing you want to do.”

On a broiling summer afternoon, Turley took me for a spin in his BMW and told me about some of the other Memphis mavericks he has known, such as his late buddy Sam Phillips, the white record producer who recorded such black bluesmen as B.B. King and Howlin’ Wolf and in 1952 founded Sun Records; his roster soon included Elvis, Johnny Cash, Jerry Lee Lewis, Carl Perkins and Roy Orbison. Then there is Fred W. Smith, the ex-Marine who created Federal Express, in 1971, and Kemmons Wilson, who came up with Holiday Inns, in 1952. Another local innovator, Clarence Saunders, opened the nation’s first self-service grocery store in Memphis in 1916, featuring such novelties as shopping baskets, aisle displays and checkout lines. He named it Piggly Wiggly.

We ended the day at Turley’s South Bluffs home, tearing into some fried chicken with Henry’s wife, Lynne, a musician and teacher. As the sun finally melted into the pristine Arkansas woodland across the river, we sank into some sofas to watch a PBS documentary co-directed by Memphis author and filmmaker Robert Gordon. Called “Respect Yourself: The Stax Records Story,” it’s about the Memphis label that, in the 1960s, rivaled Detroit’s Motown for first-class soul music—think Otis Redding, Carla Thomas, Sam & Dave, Isaac Hayes, the Staple Singers, Booker T. and the MG’s.

The tourist brochures tout Memphis as the home of the blues and the birthplace of rock ’n’ roll, and there are musical shrines, including the original Sun Studios on Union Avenue and Elvis’ monument, Graceland, plus two museums devoted to the city’s musical heritage—the Rock ’n’ Soul Museum (a Smithsonian Affiliate) and the Stax Museum of American Soul Music. Between them, they pay proper homage to the broad streams of influence—Delta blues, spirituals, bluegrass, gospel, hillbilly, Tin Pan Alley, Grand Ole Opry, rhythm & blues, jazz and pop—that converged in Memphis from the late 19th to the mid-20th centuries.

But the assumption that Memphis’ glory lies entirely in the past doesn’t sit well with some of the younger musicians. “There’s a little bit of resentment that when people talk about Memphis, they only talk about the blues and Elvis,” says Benjamin Meadows-Ingram, 31, a native Memphian and former executive editor at Vibe magazine. New music thrives in Memphis—a feisty indie rock scene and a bouncy, bass-driven urban sound that influenced much of Southern hip-hop. Independent record stores, such as Midtown’s Shangri-La and Goner Record, support Memphis artists. Local boy Justin Timberlake has conquered the international pop charts in recent years, and the Memphis rap group Three 6 Mafia won a 2006 Academy Award for the song “It’s Hard Out Here for a Pimp,” from the film Hustle & Flow (set in Memphis and directed by Memphian Craig Brewer). That gritty side of Memphis life doesn’t make the visitor’s guides.

Before I went to Memphis, I visited Kenneth T. Jackson, 70, a proud native son of Memphis and an urban historian at Columbia University. He and his wife, Barbara, a former high-school English teacher, were college sweethearts at Memphis State (now the University of Memphis), and she keeps a Southern magnolia in their Chappaqua, New York, front yard as a reminder of home.

The couple has fond memories of the Memphis they knew in the 1950s, when Boss Crump himself might appear with his entourage at a Friday night football game, passing out candy bars to the cheerleaders. “He had this long white hair, and he’d wear a white hat and a white suit—he was so dapper,” Barbara said. “It was as if the guardian angel of Memphis had come down to mix among the people.”

The Jacksons also remember tuning in to a hopped-up deejay named Dewey Phillips (no relation to Sam), whose nightly WHBQ radio broadcast, “Red Hot & Blue,” attracted a devoted following in both the white and African-American communities. It was Dewey Phillips who catapulted Elvis’ career on the night of July 8, 1954, when he previewed Presley’s debut single, “That’s All Right (Mama),” playing it over and over until teenagers all around town were in a fever, then hauling the astonished young crooner out of a neighborhood movie theater to submit to his first interview ever. “Just don’t say nothin’ dirty,” Phillips instructed him.

Though music people like Dewey and Sam Phillips were playing havoc with the color line, segregation was still the law of the land throughout Dixie. And race, Jackson maintains, is the inescapable starting point for understanding Memphis.

“There’s a famous saying that the Mississippi Delta begins in the lobby of the Peabody Hotel and ends on Catfish Row in Vicksburg,” he said. “It’s a rich agricultural area, drained by the river, that’s part of what is known as the Black Belt. Memphis grew up as a commercial entrepôt, a trading center for cotton, slaves, hardwood lumber and livestock—it was even the world’s largest mule market, right into the 1950s. By the turn of the last century, Memphis had become the unofficial capital of both cotton culture and the Black Belt. Beale Street was arguably the cultural heart of the African-American world.”

Today, Memphis’ population of 650,100 is 63 percent black. The nation’s 19th largest city is also the eighth poorest, with the sad distinction of having the highest U.S. infant mortality rate—twice the average. Over the past half-century, Memphis has lost ground to Atlanta and other Southern cities, and it pains Jackson to talk about his hometown’s self-inflicted wounds, political corruption and downtown neglect. But he hasn’t given up. “I think cities can change,” he said. “If New York can do it, why the hell can’t Memphis?” At a time when many cities have lost their distinctive character, Jackson thinks the effort is worth it. “Memphis still has soul,” he added.

__________________________

I closed my eyes on the flight from New York, lulled by an all-Memphis iPod playlist heavy on underappreciated jazzmen such as Phineas Newborn Jr., George Coleman and Jimmie Lunceford. When the pilot announced our descent to Memphis International Airport, I flipped up the window shade to find column after column of fiercely billowing thunderheads. We shuddered through them into a vista of flat, lush farmland edging into suburban developments with curlicued street plans, then, near the airport, a series of immense truck terminals and warehouses. On the runway, I glimpsed the vast fleet of purple-tailed FedEx jets that help account for Memphis International’s ranking as the world’s busiest cargo airport.

After checking in to my hotel, I jumped aboard the Main Street trolley at the Union Avenue stop around the corner. Memphis trolleys are restored trams from cities as far-flung as Oporto, Portugal, and Melbourne, Australia, with brass fittings, antique lighting fixtures and hand-carved mahogany corbels. At every turn, our conductor pointed out highlights in a melodious accent that was hard to pin down. Louisiana Cajun, maybe? “No, sir, I’m from Kurdistan,” allowed the conductor, Jafar Banion.

When we passed AutoZone Park, home of baseball’s Triple-A Memphis Redbirds, Banion noted that the new downtown ballpark—the minor leagues’ answer to Baltimore’s Camden Yards—is earthquake-proof. It’s a good thing, too, since Memphis lies at the southern end of the New Madrid seismic fault system; in 1812, a titanic quake temporarily caused a portion of the Mississippi to run backward. Soon we caught sight of the Pyramid—the 32-story stainless steel–clad arena on the banks of the Mississippi—a nod to Memphis’ namesake (and sister city) on the Nile in Egypt. Though eclipsed as a sports and convention venue by the newer FedExForum, the Pyramid remains the most striking feature of the Memphis skyline. “Every time I see it, it reminds me of my uncle and his camels,” Banion said, laughing.

The lower end of the trolley route swings through the South Main Arts District, which is dotted with lofts, galleries and eateries, among them the Arcade Restaurant, Memphis’ oldest, where you can sip a malted in Elvis’ favorite booth or relive a scene from Jim Jarmusch’s 1989 film Mystery Train, some of which was shot there.

The Lorraine Motel is just a short walk from the Arcade and a half-mile south of Beale Street. In its day, it beckoned as a clean, full-service establishment with decent food—one of the few lodgings in Memphis that welcomed African-Americans, Sarah Vaughan and Nat King Cole among them. Even after the Civil Rights Act of 1964 dismantled legal barriers, the Lorraine was that rare place where blacks and whites could mingle comfortably. In hot weather, a mixed group of musicians might drop in from recording sessions at Stax, which had no air conditioning, to cool off in the Lorraine swimming pool. Guitarist Steve Cropper—one of several white artists integral to the Stax sound—co-wrote “In the Midnight Hour” with Wilson Pickett just a few doors down from No. 306, the $13-a-night room where King customarily stayed.

Shortly after 6 p.m. on the evening of April 4, 1968, the civil rights leader stood outside that room, bantering with friends down in the parking lot. One of them was a respected Memphis saxophone player named Ben Branch, who was scheduled to perform at a mass rally that night. “Ben, make sure you play ‘Precious Lord, Take My Hand’ in the meeting tonight,” King called out. “Play it real pretty.” Those were his last words.

Barbara Andrews, 56, has been curator of the adjoining National Civil Rights Museum since 1992. “It is a very emotional place,” she said of the Lorraine. “You see people crying, you see people sitting in silence.” The exhibits trace the painful, determined journey from abolitionism and the Underground Railroad to the breakthroughs of the 1950s and ’60s. You can board an early ’50s-vintage city bus from Montgomery, Alabama, and sit up front near a life-size plaster statue of Rosa Parks, who famously refused to give her seat to a white man; every minute or so, a recording of the driver asks her to move to the back. (“No!” snapped Durand Hines, a teenager in town from St. Louis for a family reunion.) The museum’s narrative moves on to Birmingham and Selma and Dr. King’s work in Chicago and the Memphis sanitation workers’ strike of 1968. As you approach the end—the carefully preserved motel rooms and the balcony itself—you hear a recording of Mahalia Jackson singing “Precious Lord” with a calm, irresistible power, just as she did at King’s funeral: “Precious Lord, take my hand / Lead me on, let me stand.”

Not everyone makes it all the way. Andrews recalls walking the late African-American Congresswoman Barbara Jordan through the museum. “Actually I was pushing her wheelchair—and she did pretty well through most of the exhibits. But by the time we had come around by Chicago—you could hear Mahalia singing—she asked that I turn back. She said she knew how this ends. It was just too much for her to bear.”

__________________________

On April 17, 1973, a Dassault Falcon jet took off from Memphis bearing the first Federal Express overnight delivery. That night, 14 Falcons carried 186 packages to 25 cities. The original plane is on display at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum’s Udvar-Hazy Center.

Fred W. Smith had dreamed of creating such a service as an undergrad at Yale, where he was a flying buddy of John Kerry and a frat brother of George W. Bush. During two tours of duty in Vietnam, where Smith flew on more than 200 combat missions, he gained valuable exposure to complex logistical operations. It paid off. Today, Memphis-headquartered FedEx is a $33 billion company serving 220 countries and handling more than 7.5 million shipments daily. “Memphis without Fred Smith and FedEx is hard to conceive,” says Henry Turley. “FedEx is the economic engine.”

Memphis is also a major river port, rail freight center and trucking corridor, and a key distribution hub for Nike, Pfizer, Medtronic and other companies. At the cavernous FedEx SuperHub at Memphis International, where packages tumble along 300 miles of automated sorting lines, the noise level is deafening. Handlers wear earplugs, back belts and steel-toed shoes. The pace quickens after 11 p.m. “At night, we gang-tackle everything,” said Steve Taylor, a manager of the SuperHub control room, who shepherded me around. “We’re sorting 160,000 packages an hour.”

With a payroll of more than 30,000, FedEx is by far Memphis’ largest employer. Those jobs are a key to undoing the legacies of poverty and racial inequality, said Glenn D. Sessoms, 56, who was then managing daytime sorting operations at the SuperHub. “Think about it—there’s probably about 2,000 or more African-Americans on my 3,500-person shift here,” he said. “Well, a lot of them are managers, team leaders and ramp agents.”

Sessoms, an African-American, came to Memphis in 1994 and became active with the National Civil Rights Museum and the United Way. “This is still fundamentally a racially divided city,” he said. “But I think people are starting to figure out how can we live better together, support one another’s agendas.”

He pointed out his office window to the airport tarmac, where FedEx handlers were ferrying packages to a DC-10. “It’s hard work out here,” Sessoms said. “Especially when it’s 98 degrees out, which means it’s 110 down there. But people who work here have pride. They can say, ‘I’m throwing packages out here in the heat, but I’ve got a good job with good benefits. I’m wearing a uniform.’” And they’re the backbone of FedEx, he said. “I’m an executive vice president. If I don’t come to work, we’re OK. If they don’t come to work, we’re S.O.L.”

“What’s that?” I asked.

“Sh-t outta luck.”

__________________________

There are said to be some excellent high-end restaurants in Memphis. I never found out. I went for the barbecue. The Memphis variety is all about pork—ribs or shoulder meat, prepared “dry” (with a spicy rub) or “wet” (with a basted-on sauce). I’m still dreaming about some of the places where I pigged out. There’s the much-celebrated Rendezvous, tucked away in a downtown passageway called Gen. Washburn Alley (named for a Union general who fled in his nightclothes during a Rebel cavalry raid in 1864). Then there’s Payne’s Bar-B-Q, a converted Exxon service station out on Lamar Avenue. Walk past the gumball machine into a large room with a salmon-colored cinder-block wall. Belly up to the counter and order a “chopped hot”—a pork shoulder sandwich on a soft bun with hot sauce and mustardy slaw. Crunchy on the outside, smoky tender inside. With a Diet Coke, it comes to $4.10—possibly the greatest culinary bargain in these United States. Payne’s was opened in 1972 by the late Horton Payne, whose widow, Flora, carries on the tradition today. I asked her how business was going. “It’s holding its own,” she said. “Damn right!” thundered a customer nearing the counter. “Give me two just like his, all right, baby?” She flashed a smile and turned toward the kitchen.

But the heavyweight champ has to be Cozy Corner, at the intersection of North Parkway and Manassas Street. The sign over the front door is hand-lettered. The charcoal cooker is just inside. I ordered ribs. White bread makes a good napkin to sop up what happens next. My sauce-splattered notes from that foray consist of two words: the first is “Holy”; the second is unreadable. Smokes, maybe.

__________________________

The mighty Mississippi has spawned triumph and tragedy, song and legend—and, as I learned one sultry afternoon, a great number of scary-looking catfish. The kind that weigh more than your mama. In Life on the Mississippi, Mark Twain tells of a catfish over six feet long, weighing 250 pounds. Who knows? Today some catfish competitions require anglers to strap on lie detectors to verify they didn’t cheat, say, by submitting the same fish that won last time.

At the Bass Pro Shops Big Cat Quest Tournament, which I attended on Mud Island, actually a peninsula jutting into the Mississippi, the catch must be brought in live (“No catfish on ice,” the rules state). This was all patiently explained to me by one of the judges, Wesley Robertson, from Jackson, Tennessee. “I’m a little-town guy,” he said, glancing warily toward the Memphis skyline.

With a possible $75,000 in cash prizes at stake, a long line of river craft inched toward the official weigh-in, bristling with rods and nets. Robertson told me the world- record catfish was actually 124 pounds. The best bait? “Shad and skipjack,” he said. The best catfishing? “James River, Virginia.” The one he dreams about? “I’ll take three dams on the Tennessee River. There’s a world record in there.” I observed that he wasn’t being very specific. He shot me a sidelong grin that made me feel I just might be catching on.

__________________________

Tad Pierson, 58, a straw-hatted blues aficionado originally from Kansas, is the Zen master of Memphis tour operators, a one-man Google of local knowledge. “I do anthro-tourism,” he told me.

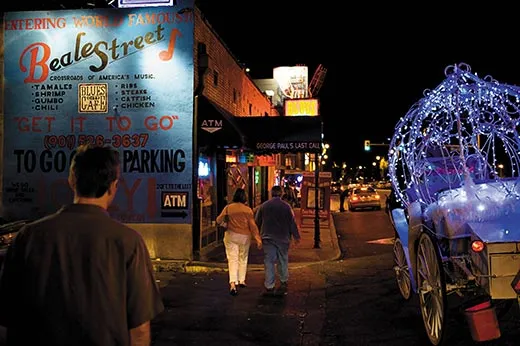

I rode shotgun in his creamy pink 1955 Cadillac for an afternoon ramble. We looped around to the juke joints near Thomas Street, which some people call “the real Beale Street.” The more interest you show, the more Pierson lights up. “I get a sense that people are called to Memphis,” he said. “It’s cool bringing them to the altar of experience.”

The largest number of worshipers go to the slightly eerie theme park that is Graceland. Maybe I was just in a bad mood, but the whole Elvisland experience—the Heartbreak Hotel & RV Park, the “Elvis After Dark” exhibit, Elvis’ private jet and so on—seemed to me a betrayal of what was most appealing about Elvis, early Elvis at any rate: his fresh, even innocent musical sincerity. There’s an undercurrent of cultural tension there, with some visitors reverentially fawning over every scrap of Presleyana, while others snicker, secure in the knowledge that their home-decorating taste is more refined than that of a slick-coifed rocker born in a two-room shotgun shack in Mississippi at the height of the Depression—who, even posthumously, earns $55 million a year. Actually, the white-columned house and grounds he bought for himself and his extended family are quite pretty.

I was struck by the fact that Elvis’ humble birthplace—there’s a scale model of it at Graceland—was almost identical to W. C. Handy’s Memphis home, which now houses the W. C. Handy Museum on Beale Street. The composer’s first published work, 1912’s “Memphis Blues,” began as a jaunty campaign song for Boss Crump, and Handy eventually wrote many popular songs, including “St. Louis Blues” and “Beale Street Blues”: “If Beale Street could talk, if Beale Street could talk / Married men would have to take their beds and walk.”

Late one afternoon, hours before the street ginned up for real, I was leaning into the open-air bar window of B.B. King’s Blues Club at Beale and South Second, checking out a singer named Z’Da, who’s been called the Princess of Beale Street. A tall man with a white T-shirt and salt-and-pepper hair approached me, pulling on a cigarette. “I saw you taking pictures of W. C. Handy’s house a little while ago,” he said, smiling.

We got to talking. He told me his name was Geno Richardson and he did odd jobs for a living. “I bring water for the horses,” he said, pointing over to one of the carriages that take tourists around the area. He had heard stories about Beale Street in its 1920s heyday, when prostitution and gambling flourished and George “Machine Gun” Kelly was a small-time bootlegger here. Talented bluesmen could always find work, but it wasn’t a place for the faint of heart. In the ’50s, “Elvis was about the only white guy who could come here after dark,” Richardson said. “And that was because B.B. King, Howlin’ Wolf and those guys sort of took him under their wing.”

Today’s throbbing two-block entertainment district is well-patrolled by Memphis police; it’s all that’s left of the old Beale Street, which stretched eastward with shops, churches and professional offices before they were razed in misbegotten urban renewal schemes. Across the intersection from the Handy museum, in the basement of the First Baptist Beale Street Church, the famed civil rights advocate and feminist Ida B. Wells edited her newspaper, Free Speech. In 1892, after the lynching of three black grocery store owners—friends of hers who had been targeted for taking business away from whites—Wells urged blacks to pack up and leave Memphis; a mob then ransacked the paper’s office and Wells fled the city herself. Seven years later, on an expanse of land adjoining the same house of worship, Robert R. Church Sr., a former slave who became the South’s first black millionaire, created Church Park and Auditorium—the city’s first such amenities for African-Americans—and later hired W. C. Handy to lead the park’s orchestra. Booker T. Washington spoke there, and President Theodore Roosevelt drew throngs to this now-forgotten patch of turf.

Richardson, 54, asked me where I was from, and when I said New York, he touched the Yankees logo on his baseball cap and smiled again. Then he handed me a copy of the weekly Memphis Flyer, opened to the music listings. “This has everything you need,” he said. I gave him $5 and we wished each other well.

__________________________

Through his films and writings—which include a biography of Muddy Waters and It Came From Memphis, a captivating study of the Bluff City’s racial and musical gestalt during the pivotal Sun-to-Stax era—Robert Gordon, 49, has become a beacon of Memphis culture.

I met Gordon for lunch one day at Willie Moore’s soul food place on South Third Street, which, he pointed out, is the continuation of Highway 61, the fabled blues road that slices through the Mississippi Delta from New Orleans to Memphis. “All roads in the Delta lead to 61, and 61 leads to Memphis,” Gordon said. “The way the moon creates tidal flows, the Delta creates social patterns in Memphis.”

We drove around Soulsville, USA, the predominantly black section where Aretha Franklin and several other important music figures came from. Gordon turned down South Lauderdale to show me the studios of Hi Records, the label best known for recording Al Green, who still performs. The street has been renamed Willie Mitchell Boulevard, after the late musician and producer who was to Hi Records what Sam Phillips was to Sun. There’s common ground there, Gordon suggested. “I think that what runs through much of the stuff in Memphis that has become famed elsewhere is a sense of individuality and of independence, establishing an aesthetic without being concerned about what national or popular trends are,” Gordon said.

Just a few blocks farther along we approached the Stax Museum and the adjoining Stax Music Academy, where teenagers enjoy first-class facilities and instruction. I met some of the students and teachers the next evening; it’s impossible not to be moved by the spirit of optimism they embody and their proud (but also fun-loving) manner. The hope is that the new Stax complex, which opened in 2002, will anchor a turnaround in this historically impoverished community.

“I like the whole message of what’s happened to Delta culture, that it’s gained respect,” Gordon said. “It didn’t yield to pressures, it maintained its own identity, and ultimately, the world came to it, instead of it going to the world. And I feel like you can read that in the buildings and streets and history and people and happenstance exchanges—all of that.”

__________________________

“Put your hands together for Ms. Nickki, all the way from Holly Springs, Mississippi!” the emcee yelled to a packed house. It was Saturday night at Wild Bill’s, a juke joint wedged next to a grocery store on Vollintine Avenue. The drummer was laying down a heavy backbeat, accompanied by a fat bass line. Wild Bill’s house band, the Memphis Soul Survivors, includes sidemen who have backed B.B. King, Al Green—everybody—and the groove is irresistible. Then Ms. Nickki, a big-voiced singer with charm to spare, stepped to the mike.

As it happened, the club’s founder, “Wild Bill” Storey, had died earlier that week and had been laid to rest at the veterans’ cemetery in Germantown just the day before. “I almost didn’t come. I cried my eyes out,” Ms. Nickki said tenderly.

They say there are two very good times to sing the blues—when you’re feeling bad, and when you’re feeling good. Sometimes they overlap, like the sacred and the profane. So Ms. Nickki decided to show up. “Y’all came to the best doggone blues joint this side of the moon!” she declared, reaching deep and belting out one impassioned verse after another in Wild Bill’s honor. She turned up the heat with a B.B. King blues: “Rock me baby, rock me all night long / I want you to rock me—like my back ain’t got no bone.”

Wild Bill’s is a long narrow space with red walls and ceiling fans and a tiny bar and kitchen in the back. People were drinking 40-ounce beers in plastic cups at communal tables, laughing and carrying on, black and white, all ages. Fourteen dancers crammed into a space big enough for eight, right up where the band was playing. From a corner table in the back, under a bulletin board festooned with hundreds of snapshots, three smartly dressed young women spontaneously launched into a backup vocal riff borrowed from an old Ray Charles hit—“Night ’n’ day...[two beats]...Night ’n’ day”—spurring on both the band and the dancers. The Raelettes would have been proud.

“Anyone here from the Show-Me State?” Ms. Nickki asked the crowd between songs. A 40-ish woman in a low-cut dress raised her hand.

“You look like a show-me girl!” Ms. Nickki said, to raucous laughter. Then she piped up: “I was born in Missouri, ’cross the line from Arkansas / Didn’t have no money, so I got in trouble with the law.”

Actually, Ms. Nickki was born in 1972 in Holly Springs, Mississippi, like the emcee had said. Nicole Whitlock is her real name, and she didn’t even like the blues when she was growing up. “My real taste of the blues came after I got to Memphis,” she told me. “Back home, we were church folks—gospel, gospel, gospel.”

__________________________

Henry Turley’s office is in the historic Cotton Exchange Building at Union Avenue and Front Street, once known as Cotton Row. Turley told me a high percentage of the nation’s cotton trading still takes place in Memphis, and the traders have the same damn-the-torpedoes attitude that gave Memphis so much of its character through the years.

“They’re wild and free, and they do what the hell they want to do,” Turley said. “A lot of these cotton guys, they’re mad gamblers, you know, betting on cotton futures with money they never dreamed they had, leveraging things at a huge multiple.”

Turley describes himself and his approach to real estate development in more modest terms. “I have small ideas,” he said. “I tend to think those are better ideas, and I tend to think that they become large ideas if they’re replicated in discrete and different ways, sufficiently. My small idea is to create neighborhoods where life is better, and richer, and more interesting and just more fulfilling for the people who choose to live there.”

Turley seems to know everybody in Memphis—from the mayor to the musicians and the street people. It’s impossible to drive around with him without stopping every block or so for another friendly exchange.

“Hey, you’re lookin’ good, man,” he called out to a young black homeowner in Uptown who’d been ailing the last time they spoke. Within the next five minutes, they swapped spider-bite remedies, Turley dispensed some real estate advice, and the man passed on a suggestion about putting more trash cans in the neighborhood.

“I knew a guy who once said to me, ‘You know, Memphis is one of the few real places in America,’” Turley said. “‘Everything else is just a shopping center.’ He’s right. Memphis is a real place.”

He pulled up in a pleasant new square hacked out of an abandoned lot and pointed out the window. “Look at that!” I poked my head out and peered up to see a miniature, octagon-shaped white house perched on a tall metal pole.

“Looks like a birdhouse to me,” Turley said, savoring the word, even singing it slightly.

Jamie Katz writes often on arts and culture. Pulitzer Prize-winning photographer Lucian Perkins lives in Washington, D.C.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jamie-Katz-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jamie-Katz-240.jpg)