The Story of Thunder Mountain Monument

An odd and affecting monument stands off a Nevada highway as a testament to one man’s passions

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/road-connecting-monument-and-Chief-Rolling-Thunder-Mountains-hidden-retreat-631.jpg)

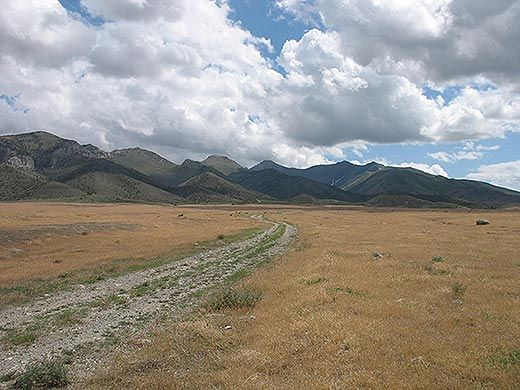

There are many unusual sights in the vast emptiness along I-80 east of Reno. Steam belching from the hot spring vents near Nightingale. Miles of white gypsum sand with hundreds of messages scripted in stones and bottles. And near the exit to Imlay, a tiny town that used to be a stop for the first transcontinental railroad, an edifice of human oddness.

Thunder Mountain Monument looks as if the contents of a landfill popped to the surface and fell into a pattern over five acres that is part sculpture garden, part backyard fort, part Death Valley theme park. I discovered the monument five years ago on a road trip and have visited it every year since. Not far from the dirt parking lot—usually empty— there’s a gate through a fence made of driftwood, bedsprings, wrecked cars and rusted pieces of metal painted with garbled words about the mistreatment of Native Americans. Inside the fence, a smaller fence bristles with No Trespassing signs and surrounds a rambling three-story structure made of concrete, stone and bottles, with old typewriters, televisions, helmets, even a bunch of plastic grapes worked into the walls. Dozens of sculptures with fierce faces encircle the structure and dozens more are part of the structure itself. At the very top, a tangle of giant white loops makes the building look as if it’s crowned with bleached bones.

On my first visit to Thunder Mountain, the desert wind played a tune over the outward-facing bottles in the concrete. Some of the tumbled-down stones near the fence were within reach—big chunks of quartz and copper ore and agate, a temptation to rockhounds like me. But there was a sign declaring Thunder Mountain Monument a state of Nevada historic site and another asking visitors to refrain from vandalism. All I took was pictures.

But that stop made me curious. What were the origins of this strange outpost? The story began 40 years ago, when a World War II vet reinvented himself on this site. He had been called Frank Van Zant most of his life and had worked, at various times, as a forest ranger, sheriff, assistant Methodist pastor and museum director. He had eight children, then his wife died and, later, one of his sons committed suicide. In 1968, he showed up at his oldest son Dan’s house with a new wife and all his possessions packed into a 1946 Chevy truck and a travel trailer. He was headed east, he told Dan, and was going to build an Indian monument.

“I’m going where the Great Spirit takes me,” he said.

Van Zant had always been interested in Native American history and artifacts; gradually, that interest had become an obsession. He believed himself to be a quarter Creek Indian and took on a new name, Chief Rolling Thunder Mountain. When he arrived in Imlay, he began covering his trailer with concrete mixed with stones he’d dragged down from the mountains. Although he’d never done any sort of art before, Thunder turned out to be a whiz at sculpting wet concrete. One of his first pieces was a large, somber statue of the son who killed himself, dressed in a blue button-down shirt. Others were his Native American heroes: Sarah Winnemucca, the Paiute peacemaker; the Aztec god Quetzalcoatl; Standing Bear, a peaceful chief of the Ponca tribe who was imprisoned for leaving Indian territory without permission. Still others were of Thunder himself: one as a mighty chief wielding a lightning bolt to warn away intruders, another as a bent, humbled figure with a downcast face.

Thunder began to attract followers—up to 40 people at the compound’s height—whom he exhorted to have a “pure and radiant heart.” Soon, there were other rooms adjoining the old travel trailer, then a second story with a patio and tiny third floor. This was the heart of the monument, an inside-out museum with the artwork and messages on the exterior and the Thunders living within. There were other buildings, too, and Thunder was the architect, the contractor and the supplier of materials. He scavenged a 60-mile area around the monument, picking up refuse and stripping wood from tumbled down buildings in ghost towns. “I’m using the white mans’ trash to build this Indian monument,” he told everyone.

But in the 1980s, fewer people lingered at Thunder Mountain and bleakness descended upon its creator. Increasingly destitute, he sold his prized collection of Native artifacts. Then an act of arson destroyed all the buildings except the monument itself, and in 1989, his wife and new passel of children moved away. At the end of that year, he wrote a goodbye letter to Dan and shot himself.

For centuries, people with an evangelical bent have built structures along roads to hook passersby with their message—from the shrines built along pilgrimage routes in Europe to the Golgotha Fun Park near Kentucky’s Mammoth Cave. Thunder was unknowingly working in this tradition, welcoming tourists to see the art and hear the lecture. In the process he created what’s often referred to as a “visionary environment,” which some people view as a collection of junk and others consider a valuable folk-art installation. Leslie Umberger, curator at the John Michael Kohler Arts Center in Sheboygan, Wisconsin, an institution interested in preserving such sites, says that hundreds of them have disappeared before people realized they were worth saving.

“These environments were rarely created with the intention of lasting beyond the life of the artist,” Umberger explains. “They’re often ephemeral and exposed to the elements. Sometimes people don’t understand that these places embody aspects of a region’s time and place and culture that are important and interesting.”

Years ago, Dan asked his father why he built the white loops and arches on top of the monument. “In the last days, the Great Spirit’s going to swoop down and grab this place by the handle,” Thunder replied.

But vandals and the desert might get it first. Since his father’s death, Dan’s been steadily fighting both of them. Bored local teenagers break the embedded bottles and the monument windows, which are hard to replace because they’re made from old windshields. Sculptures disappear. The fences keep out the cows—this is open range country—but other animals gnaw and burrow their way in. Winter storms tear at some of the monument’s fragile architectural flourishes. Dan tries to come once a month to work on the place and has a local man look in on it several days a week, but presevation is a tough job. He tried to give it to the state of Nevada, but officials reluctantly declined, saying they didn’t have the resources.

For now, Thunder Mountain still stands. The sculptures are as fierce as ever, the messages fainter but not subdued. When the trees on the site are bare, you can see the monument’s sinewy topknot from far away. It’s easy to imagine the Great Spirit reaching down to snatch it away. That’s the kind of thought you have in the middle of nowhere.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.