The Struggle Within Islam

Terrorists get the headlines, but most Muslims want to reclaim their religion from extremists

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Presence-Islam-Anti-Mubarak-demonstrators-631.jpg)

After the cold war ended in 1991, the notion of a “clash of civilizations”—simplistically summarized as a global split between Muslims and the rest of the world—defined debates over the world’s new ideological divide.

“In Eurasia the great historic fault lines between civilizations are once more aflame,” the Harvard political scientist Samuel Huntington wrote in a controversial 1993 essay for Foreign Affairs. “This is particularly true along the boundaries of the crescent-shaped Islamic bloc of nations from the bulge of Africa to central Asia.” Future conflicts, he concluded, “will not be primarily ideological or primarily economic” but “will occur along the cultural fault lines.”

But the idea of a cultural schism ignored a countervailing fact: even as the outside world tried to segregate Muslims as “others,” most Muslims were trying to integrate into a globalizing world. For the West, the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, obscured the Muslim quest for modernization; for Muslims, however, the airliner hijackings accelerated it. “Clearly 9/11 was a turning point for Americans,” Parvez Sharma, an Indian Muslim filmmaker, told me in 2010. “But it was even more so for Muslims,” who, he said, “are now trying to reclaim space denied us by some of our own people.”

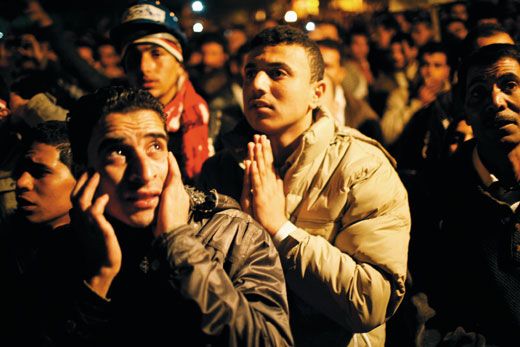

This year’s uprisings in Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, Syria, Yemen and beyond have rocked the Islamic world, but the rebellions against geriatric despots reflect only a small part of the story, obscuring a broader trend that has emerged in recent years. For the majority of Muslims today, the central issue is not a clash with other civilizations but rather a struggle to reclaim Islam’s central values from a small but virulent minority. The new confrontation is effectively a jihad against The Jihad—in other words, a counter-jihad.

“We can no longer continuously talk about the most violent minority within Islam and allow them to dictate the tenets of a religion that is 1,400 years old,” Sharma told me after the release of A Jihad for Love, his groundbreaking documentary on homosexuality within Islam.

The past 40 years represent one of the most tumultuous periods in Islam’s history. Since 1973, I’ve traveled most of the world’s 57 predominantly Muslim countries to cover wars, crises, revolutions and terrorism; I sometimes now feel as if I’ve finally reached the climax—though not the end—of an epic that has taken four decades to unfold.

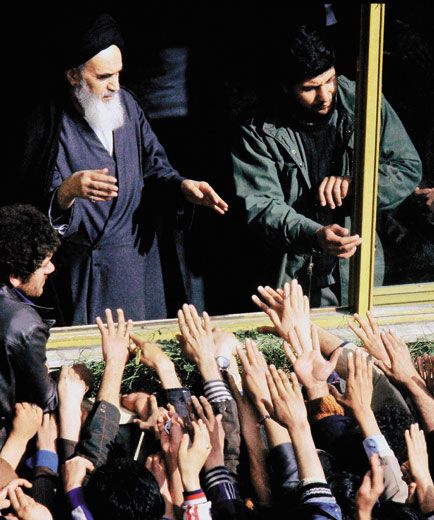

The counter-jihad is the fourth phase in that epic. After the Muslim Brotherhood emerged in Egypt in 1928, politicized Islam slowly gained momentum. It became a mass movement following the stunning Arab loss of the West Bank, Golan Heights, Gaza and Sinai Peninsula in the 1967 war with Israel. The first phase peaked with the 1979 revolution against the Shah of Iran: after his fall, clerics ruled a state for the first (and, still, only) time in Islam’s history. Suddenly, Islam was a political alternative to the dominant modern ideologies of democracy and communism.

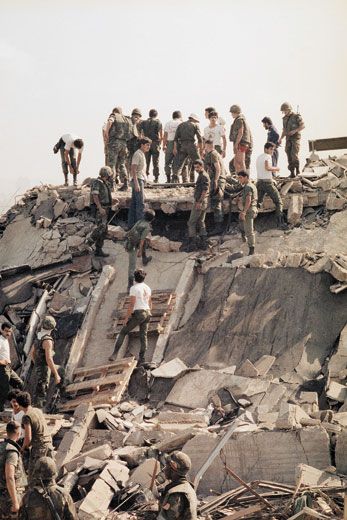

The second phase, in the 1980s, was marked by the rise of extremism and mass violence. The shift was epitomized by the truck bombing of a U.S. Marines barracks in Beirut in 1983. With a death toll of 241 Marines, sailors and soldiers, it remains the deadliest single day for the U.S. military since the first day of the Tet Offensive in Vietnam in 1968. Martyrdom had been a central tenet among Shiite Muslims for 14 centuries, but now it has spread to Sunni militants, too. Lebanese, Afghans and Palestinians took up arms to challenge what they viewed as occupation by outside armies or intervention by foreign powers.

In the 1990s, during the third phase, Islamist political parties began running candidates for office, reflecting a shift from bullets to ballots—or a combination of the two. In late 1991, Algeria’s Islamic Salvation Front came close to winning the Arab world’s first fully democratic election, until a military coup aborted the process and ushered in a decade-long civil war. Islamic parties also took part in elections in Lebanon, Jordan and Egypt. From Morocco to Kuwait to Yemen, Islamist parties captured voters’ imagination—and their votes.

Then came 9/11. The vast majority of Muslims rejected the mass killing of innocent civilians, but still found themselves tainted by Osama bin Laden and Al Qaeda, a man and a movement most neither knew nor supported. Islam became increasingly associated with terrorist misadventures; Muslims were increasingly unwelcome in the West. Tensions only grew as the United States launched wars in Afghanistan and Iraq—and the new, elected governments there proved inept and corrupt.

Yet militant Islam, too, failed to deliver. Al Qaeda excelled at destruction but provided no constructive solutions to the basic challenges of everyday life. Almost 3,000 people died in the 9/11 terrorism spectaculars, but Muslim militants killed more than 10,000 of their brethren in regionwide attacks over the next decade—and unleashed an angry backlash. A new generation of counter-jihadis began to act against extremism, spawning the fourth phase.

The mass mobilization against extremism became visible in 2007, when tribal leaders in Iraq, organized by a charismatic chief named Sheik Abdul Sattar Abu Risha, deployed a militia of some 90,000 warriors to push Al Qaeda of Mesopotamia out of Anbar, Iraq’s most volatile province. In addition, Saudi and Egyptian ideologues who had been bin Laden’s mentors also began publicly repudiating Al Qaeda. In 2009, millions of Iranians participated in a civil disobedience campaign that included economic boycotts as well as street demonstrations against their rigid theocracy.

By 2010, public opinion polls in major Muslim countries showed dramatic declines in backing for Al Qaeda. Support for bin Laden dropped to 2 percent in Lebanon and 3 percent in Turkey. Even in such pivotal countries as Egypt, Pakistan and Indonesia—populated by vastly different ethnic groups and continents apart—only around one in five Muslims expressed confidence in the Al Qaeda leader, the Pew Global Attitudes Project reported.

Muslim attitudes on modernization and fundamentalism also shifted. In a sampling of Muslim countries on three continents, the Pew survey found that among those who see a struggle between modernizers and fundamentalists, far more people—two to six times as many—identified with modernizers. Egypt and Jordan were the two exceptions; in each, the split was about even.

In the first month of Egypt’s uprising in 2011, another poll found that 52 percent of Egyptians disapproved of the Muslim Brotherhood and only 4 percent strongly approved of it. In a straw vote for president, Brotherhood leaders received barely 1 percent of the vote. That survey, by the pro-Israeli Washington Institute of Near East Policy, also found that just two out of ten Egyptians approved of Tehran’s Islamic government. “This is not,” the survey concluded, “an Islamic uprising.”

Then what is it?

It seems, above all, an effort to create a Muslim identity that fits in with political changes globally. After the revolts in Egypt and Tunisia, many Arabs told me they wanted democratic political life compatible with their culture.

“Without Islam, we will not have any real progress,” said Diaa Rashwan of Cairo’s Al Ahram Center for Political and Strategic Studies. “If we go back to the European Renaissance, it was based on Greek and Roman philosophy and heritage. When Western countries built their own progress, they didn’t go out of their epistemological or cultural history. Japan is still living in the culture of the Samurai, but in a modern way. The Chinese are still living the traditions created by Confucianism. Their version of communism is certainly not Russian.

“So why,” he mused, “do we have to go out of our history?”

For Muslims, that history now includes not only Facebook and Twitter, but also political playwrights, stand-up comics, televangelist sheiks, feminists and hip-hop musicians. During Iran’s 2009 presidential election, the campaign of opposition candidate Mehdi Karroubi—a septuagenarian cleric—distributed 1,000 CDs containing pro-democracy raps.

The job-hungry young are a decisive majority in most Muslim countries. The median age in Egypt is 24. It is 22 or younger in Pakistan, Iraq, Jordan, Sudan and Syria. It is 18 in Gaza and Yemen. One hundred million Arabs—a third of the population in 22 Arab countries—are between ages 15 and 29. Tech-savvy and better-educated than their parents, they want a bright future—from jobs and health care to a free press and a political voice. The majority recognizes that Al Qaeda can’t provide any of that.

The youth-inspired upheavals of the euphoric Arab Spring have stunned Al Qaeda as much as the autocrats who were ousted. In Egypt and Tunisia, peaceful protests achieved in days what extremists failed to do in more than a decade. A week after Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak resigned in February, Al Qaeda released a new videotape from bin Laden deputy Ayman al-Zawahiri on which he rambled for 34 minutes and made no mention of Mubarak’s exit. After a covert U.S. raid killed bin Laden on May 2, Al Qaeda released a tape on which he congratulated his restive brethren. “We are watching with you this great historic event and share with you the joy and happiness.” The operative word was “watching”—as in from afar. Both men seemed out of the loop.

At the same time, the counter-jihad will be traumatic and, at times, troubling. The Arab Spring quickly gave way to a long, hot summer. Change in the last bloc of countries to hold out against the democratic tide may well take longer than in other parts of the world (where change is still far from complete). And Al Qaeda is not dead; its core will certainly seek retribution for the killing of bin Laden. But ten years after 9/11, extremism in its many forms is increasingly passé.

“Today, Al Qaeda is as significant to the Islamic world as the Ku Klux Klan is to the Americans—not much at all,” Ghada Shahbender, an Egyptian poet and activist, told me recently. “They’re violent, ugly, operate underground and are unacceptable to the majority of Muslims. They exist, but they’re freaks.

“Do I look at the Ku Klux Klan and draw conclusions about America from their behavior? Of course not,” she went on. “The KKK hasn’t been a story for many years for Americans. Al Qaeda is still a story, but it is headed in the same direction as the Klan.”

Adapted from Rock the Casbah: Rage and Rebellion Across the Islamic World, by Robin Wright. Copyright © 2011. With the permission of the publisher, Simon & Schuster.

Robin Wright is a fellow at the Woodrow Wilson Center and the U.S. Institute of Peace.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.