The Tallest, Strongest and Most Iconic Trees in the World

Where to see the greatest trees in the world

Baobab trees stud the brown plains of Africa like uprooted, upside-down oaks. These bizarro beasts are growing in Botswana. The biggest baobabs may be thousands of years old. Photo courtesy of Flickr user prezz.

Last week I wrote about the cork trees of the Iberian Peninsula, those great, handsome figures so emblematic of the interior plains of Portugal and Spain. But further abroad are many more trees of great stature and symbolic value—trees that inspire, trees that make us stare, trees that provide and trees that bring to their respective landscapes spirit and grandeur. Here a few of the most celebrated, most famous and most outlandish trees of the Earth.

Baobab. Its bark is fire resistant. Its fruit is edible. It scoffs at the driest droughts. It shrugs, and another decade has passed. It is the baobab, one of the longest-living, strangest looking trees in the world. Several species exist in the genus Adansonia, mostly in the semi-deserts of Africa and southern Asia. They can grow to be nearly 100 feet tall—but it’s the baobab’s bulk and stature that is so astonishing; many have trunks 30 feet in diameter. The Sunland Baobab of South Africa is far bigger still and is reportedly more than 6,000 years old. Its trunk, like those of many old baobabs, is hollow and—as a tourist attraction—even features a small bar inside. Baobab trees are leafless for much of the year and look rather like an oak that has been uprooted and replanted upside down. Numerous legends attempt to explain the bizarre and awesome appearance of the baobab, but if you visit the great Sunland Baobab, just let your jaw drop—and go inside for a drink.

Coconut palm. Where would a tropical beach be without one of the most recognizable of tree figures in the world—the coconut palm? Of 1,500 palm species in the world, just one—Cocos nucifera—produces coconuts, the wonderful fruit that makes desserts, curries and beers delicious, bonks unknown numbers of people each year when it falls, never drops far from the tree but will float across oceans if given the chance. As a provider of nourishment and material for mankind, the coconut is priceless. One study reported 360 uses of the tree and its fatty yet watery fruits. From the Philippines—which leads the world, along with India, in coconut cultivation—come several proverbs commending the plant for its usefulness, like this one: ”He who plants a coconut tree, plants vessels and clothing, food and drink, a habitation for himself, and a heritage for his children.” One coconut palm will produce between 25 and 75 fruits per year over its eight or so decades of life, and, worldwide, people harvest 17 billion coconuts per year.

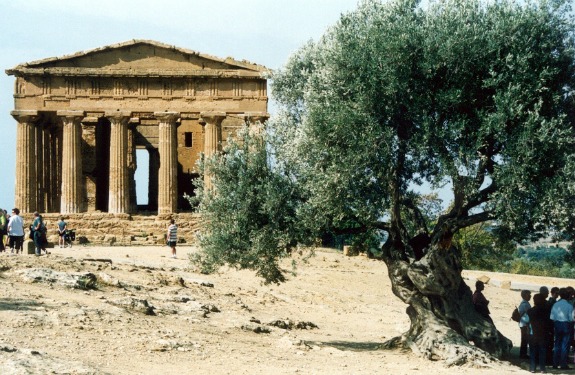

Olive. It is one of the most often cited trees in the Bible and its fruit the soul of Mediterranean cooking: the olive. In his Innocents Abroad, Mark Twain called the olive tree, and the cactus, “those fast friends of a worthless soil.” It’s true: Olive trees will produce loads of fruit in the cruelest heat and driest gravels of Spain, Portugal, North Africa, the Middle East and myriad islands in the Mediterranean. Not only that, the trees thrive in places where others may wither–and olives don’t only thrive, but thrive for century after century. The oldest olive tree is, well, no one’s certain. But in the West Bank, folks may brag that their Al Badawi tree, in the Bethlehem district, is the oldest olive of all, at between 4,000 and 5,000 years. Greeks on the island of Crete may assure that the ancient, gnarly-trunked olive tree in Vouves is the oldest—at least 3,000 years, experts guess. A half dozen other olive trees are believed to be of similar age. Introduced in the post-Columbus age to warm and arid climates worldwide, the olive tree is a continual favorite emblem for Italian restaurants everywhere and certainly one of the planet’s most appreciated providers.

Olive trees like this giant on Sicily have watched kingdoms rise and fall, have lived through a hundred droughts and, though they may date back to the time of the ancient Romans, still produce fruit every fall. Photo courtesy of Flickr user dirk huijssoon.

Fig. Mediterranean counterpart to the savory olive, the sweet fig grows in the same thirsty country and occupies the same aisles of literary history as the olive. But whereas the olive is the is the tamed and pampered tree of neat orchards and tidy groves, the fig is often a wild child—an outlier of the goat herd hills and river canyons. But the fig is hardly a reject of fruit trees. Fresh figs are one of the hottest tickets in gourmet cooking today, and in the ancient era, Olympian athletes were given figs for strength and reward. And many great and prosperous people have communed with the fig: Siddhartha meditated in the shade of a village fig for days; Jesus scolded a fig tree for having no fruit when he wanted it (Jeez, man—give the tree a break. It wasn’t fig season!); Pliny praised figs, especially the Dottato—or Kadota—variety; and the prophet Mohammed reportedly declared that if he were allowed to bring a single tree to the afterlife, it would be a fig. Amen.

Eucalyptus. The tree Down Under, the eucalyptus includes 700 species mostly endemic to Australia. Various species have been introduced to landscapes around the world, where they now dominate some regions. In California, for example, groves of eucalyptus have encroached on native grasslands, and on stands of redwoods. In Portugal the trees occur on almost 15 percent of the land area, and though useful as a source of biomass for energy production, the trees are a recognized pest. But in their native lands, eucalyptus are honorable kings. They provide essential habitat and food for the koala, for one, and are regarded highly for the medicinal and aromatic uses of its oils, often used in hand lotions and soaps. And there is a less recognized fact about eucalyptus trees–that they grow tall, super tall, taller than most of the biggest-tree-contenders in the world, taller, perhaps, than any other species. You ready? Drum roll please: The tallest eucalyptus ever, at Watts River, Victoria, was just shy of 500 feet.

Redwood. On average the tallest tree in the world, the redwood tree can grow to be taller than the spire of the Notre Dame Cathedral, occurs only in coastal California (and part of Oregon) and was the object of affection of Julia Butterfly Hill, who occupied a redwood she named Luna for three years to protect it from loggers—and succeeded. Today, relatively young and small redwood trees grow throughout their historic range, but the trees as tall as skyscrapers have mostly been felled and remain only in a handful of isolated patches of unspoiled virgin forest. Attempts to preserve them have often led to heated conflicts between loggers and environmentalists—and certainly not every person is tickled to be sharing the world with these monarchs. In 1966, then-California governor Ronald Reagan said, in response to talk of expanding Redwood National Park, “A tree is a tree. How many more do you have to look at?” That he bore such indifference toward the redwood, of all trees, has made Reagan’s sentiments among the most infamous quotes of nature-haters’.

The unmatched height and the perfect posture of the redwood brings to its coastal California habitat a church-like grandeur that will awe nearly anyone who passes among the trees. Photo courtesy of Flickr user drburtoni.

Giant Sequoia. In about they year 100 B.C., while the ancients of Crete were harvesting olives from the Vouves tree, and while the Sunland Baobab was approaching its fifth tired millennium under the African sun, a green sprout appeared on the forest floor in a still-unnamed land far, far away. It took root, and quickly surpassed the forest ferns in height, and year by year it grew into the form of a tree. A conifer, it survived fires and deer, and eventually began to assume real girth. It ascended into the canopy of tree adolescence, and, after a few dozen decades, adulthood, becoming a recognized and admired figure in the surrounding tree community. If ever this tree had died, countless others would have attended the memorial service and said fine things about it—but instead, they died, falling to disease and old age, and this spectacular tree kept on growing. It eventually was not a pillar of the community, but the pillar. When European Americans arrived in California, it’s a wonder the tree wasn’t chopped down for sport and shingles. Instead, the Sierra Nevada resident was admired by a man named Muir, given formal protection and named General Sherman. Today, this giant sequoia tree—of the genus and species Sequoiadendron giganteum—is often considered to be the most massive single organism on the planet. General Sherman weighs an estimated 2.7 million pounds, stands 275 feet tall and measures 100 feet around at the ground. No, Mr. Reagan, if you’ve seen one tree, you haven’t seen them all—but perhaps you haven’t really seen any tree until you’ve met General Sherman.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Off-Road-alastair-bland-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Off-Road-alastair-bland-240.jpg)