The Wildlife of T.C. Boyle’s Santa Barbara

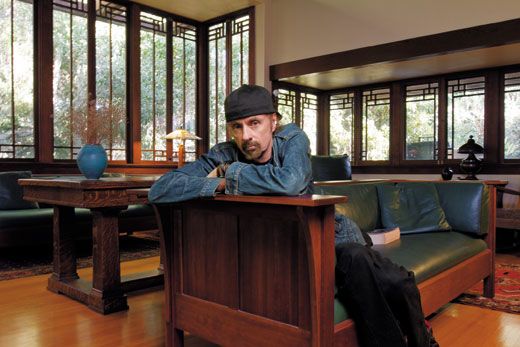

The author finds inspiration at the doorstep of his Frank Lloyd Wright-designed house near the central California town

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/My-Town-Santa-Barbara-CA-631.jpg)

Eighteen years ago, over the Labor Day weekend, I moved with my family to Montecito, an unincorporated area of some 10,000 souls contiguous to Santa Barbara. The house we’d bought was designed by Frank Lloyd Wright in 1909 and had been on the market for well over a year, as the majority of prospective buyers apparently didn’t want to negotiate the soul-wrenching, divorce-provoking drama of restoration it required. Built of redwood, with a highly flammable (and, as I was later to learn, leaky) shake roof, the house was in need of a foundation, earthquake retrofitting and rat eviction, as well as innumerable other things we didn’t want to worry ourselves with that first weekend. We stocked the larder, set up beds for the children, and then, taking advantage of the crisp, bugless nights, my wife and I tossed a mattress on one of the two sleeping porches and wound up sleeping outside off and on until we were able finally to accomplish the move of our furniture up from Los Angeles three months later.

That first night was a small miracle—sea air, wisps of fog skirting the lawn in the early hours, temperatures in the 60s—considering that we’d become accustomed to the unvarying summer blaze of the San Fernando Valley, where we’d lived for the previous decade. Never mind that we were awakened by the cries of the children informing us that strangers were in the house (an elderly couple, thinking that the place was still open for viewing, were blithely poking through the living room at 8 a.m.) or that the rats had been celebrating a sort of rat rodeo in the walls all night—we were in paradise. Behind us rose the dun peaks of the Santa Ynez Mountains, replete with the full palette of wild and semi-wild creatures and laced with hiking trails, and before us, gleaming through the gaps of the trees not five blocks distant, was the fat, shimmering breast of the mighty Pacific. The fog rolled, the children ate cereal, I unpacked boxes.

In the afternoon, under an emergent and beneficent sun, I set off exploring, digging out my mask, snorkel and flippers and heading down, on foot, to the beach. There was a crowd—this was the Labor Day weekend, after all, and Santa Barbara is, undeniably, a tourist town—but I wasn’t fazed. Do I like crowds? No. Do I like solitary pursuits (hiking the aforementioned trails, writing fiction, brooding over a deserted and wind-swept beach)? Yes. But on this occasion I was eager to see just what was going on beneath the waves as people obliviously careened past me to dive and splash while the children shrieked out their joy. The water that day, and this isn’t always the case, was crystalline, and what I was able to discover, amid the pale slash of feet and legs, was that all the various ray species of the ocean were holding a convocation, the floor of the sea carpeted with them, even as the odd bat ray or guitarfish sailed up to give me a fishy eye. Why people were not stung or spiked, I can’t say, except to presume that such things don’t happen in paradise.

Of course, there’s a downside to all this talk—the firestorms of the past few years and the mudslides that invariably succeed them, the omnipresent danger of the mega-earthquake like the one that reduced Santa Barbara’s commercial district to duff and splinters in 1925—but on an average day, Lotos-eaters that we are, we tend to forget the dangers and embrace the joys. Downtown Santa Barbara is two miles away, and there we can engage with one of our theater companies, go to the symphony or a jazz or rock club, dine out on fine cuisine, stroll through the art museum, take in lectures, courses or plays at one of our several colleges, hit the bars or drift through the Santa Barbara Mission, established in the 1780s (and which I’ve visited exactly once, in the company of my mentor and former history professor, the late Vince Knapp, who’d torn himself away from the perhaps not so paradisiacal Potsdam, New York, to come for a visit). All this is well and good. But what attracts me above all else is the way nature seems to slip so seamlessly into the urbanscape here.

For example, a portion of the property on which the house sits is zoned as environmentally sensitive because of the monarch butterflies that gather there in the fall. When they come—and the past few years their numbers have been very light, worrisomely so, though I’ve been planting milkweed to sustain their larvae—they drape the trees in a gray curtain till the sun warms them enough to get them floating around like confetti. I’ve kept the yard wild for their benefit and to attract other creatures as well. A small pond provides a year-round water source, and though we are so close to the village a good golfer could just about land a drive atop the Chinese restaurant from our backyard, a whole host of creatures makes use of it, from raccoons to opossums to the occasional coyote and myriad birds, not to mention skinks, lizards and snakes.

Unfortunately, a good portion of the forest here represents a hundred years’ growth of invasives able to thrive in a frost-free environment, black acacia and Victorian box foremost among them, but I do my best to remove their seedlings while at the same time encouraging native species like the coast live oak and Catalina cherry. So right here, right out the window, is a kind of nature preserve all in itself, and if I want a bit more adventure with our fellow species, I can drive up over the San Marcos Pass and hike along the Santa Ynez River in the Los Padres National Forest or take the passenger boat out to Santa Cruz Island, which lies about 25 miles off the coast of Santa Barbara.

This last is a relatively new diversion for me. Until two years ago I’d never been out to the Channel Islands, but had seen Santa Cruz hovering there on the near horizon like another world altogether and wondered, in the way of the novelist, just what goes on out there. The Channel Islands National Park is one of the least visited of all our national parks, incidentally, for the very simple reason that you have to lean over the rail of a boat and vomit for an hour just to get there. Despite the drawbacks, I persisted, and have visited Santa Cruz (which is four times the size of Manhattan) several times now. One of the joys of what I do is that whenever anything interests me I can study it, examine it, absorb all the stories surrounding it and create one of my own.

So, for instance, I wrote The Women, which deals with Frank Lloyd Wright, because I wanted to know more about the architect who designed the house I live in, or Drop City, set in Alaska, because our last frontier has always fascinated me—or, for that matter, The Inner Circle, about Alfred C. Kinsey, because I just wanted to know a wee bit more about sex. And so it was with the Channel Islands. Here was this amazing resource just off the coast, and I began to go there in the company of some very generous people from the Nature Conservancy and the National Park Service to explore this exceedingly precious and insular ecosystem, with an eye to writing a novel set here. (The resulting book is called When the Killing’s Done.) What attracted me ultimately is the story of the island’s restoration, a ringing success in the light of failures and extinctions elsewhere.

Introduced species were the problem. Before people settled tenuously there, the native island fox, the top terrestrial predator, had over the millennia developed into a unique dwarf form (the foxes are the size of house cats and look as if Disney created them). Sheep ranching began around the 1850s, and pigs, introduced for food, became feral. When some 30 years ago the island came into the possession of the Nature Conservancy and later the National Park Service, the sheep—inveterate grazers—were removed, but the pigs continued their rampant rooting, and their very tasty piglets and the foxes were open to predation from above. Above? Yes—in a concatenation of events Samuel Beckett might have appreciated, the native piscivorous bald eagles were eliminated from the islands in the 1960s because of DDT dumping in Santa Monica Bay, and they were replaced by golden eagles flying in from the coast in order to take advantage of the piglet supply. The foxes, which numbered some 1,500 in the mid-1990s, were reduced to less than a tenth of that number and finally had to be captive-bred while the feral pigs were eradicated, the goldens were trapped and transported to the Sierras and bald eagles were reintroduced from Alaska. And all this in the past decade. Happily, I got to tramp the ravines in the company of the biologists and trap and release the now-thriving foxes and to watch a pair of adolescent bald eagles (formidable creatures, with claws nearly as big as a human hand) be released into the skies over the island. If I’d been looking in the right direction—over my shoulder, that is—I could have seen Santa Barbara across the channel. And if I’d had better eyes—eagle eyes, perhaps—I could have seen my own house there in the forest of its trees.

Pretty exciting, all in all. Especially for a nature boy like me. And while there are equally scintillating cities like Seattle, with its amazing interface of city and nature, or even New York, where peregrine falcons roost atop the buildings and rain fine drops of pigeon blood down on the hot dog vendors below, what we have here is rare and beautiful. Still, there are times when I need to get even farther out, and that’s when I climb into the car and drive the four and a half hours up to the top of a mountain in the Sequoia National Forest, where I am writing this now while looking out on ponderosa and Jeffrey pines and not an invasive species in sight. Except us, that is. But that’s a whole other story.

T. C. Boyle’s new novel, When the Killing’s Done, is set in the Channel Islands.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.