These Five “Witness Trees” Were Present At Key Moments In America’s History

These still-standing trees are a living testament to our country’s tragic past

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1a/fe/1afe0e6d-1ec5-475f-a74f-d9e44b1aa5fc/witness-tree-in-manassas.jpg)

A witness tree begins its life like any other tree. It sprouts. It grows. And then it’s thrust into the spotlight, playing an involuntary part in a significant historic event. Often, that event is a devastating, landscape-scarring battle or other tragic moment. Once Civil War soldiers march on to their next battle, say, or a country turns its attention to healing after a terrorist attack, a witness tree remains as a biologically tenacious symbol of the past.

Witness trees have been known to hide bullets they’ve absorbed beneath new layers of wood and bark, and they heal other visible scars over time. While they may look like ordinary trees, they have incredible stories to tell.

Travelers, history lovers, some park rangers and others have embraced these exceptional trees as important, living connections to our past. In 2006, Paul Dolinsky, chief of the National Park Service’s Historic American Landscapes Survey, led the development of the Witness Tree Protection Program, a pilot project that identified an initial 24 historically and biologically significant trees in the Washington, D.C. area. Written histories and photographs of the trees are archived at the Library of Congress. “Although trees have longevity, they’re ephemeral,” says Dolinsky. “This will be a lasting record of the story a tree has to tell.”

While the pilot program has gained some traction, the number of witness trees in the U.S. remains unknown. One reason why: Some areas where witness trees may reside, like battlefields, are vast. Another reason: It can be difficult to determine a tree’s age to confirm it was alive during a significant historic event. Boring into a tree can answer that question, but it can also damage a tree so it’s not often done. In some cases, witness trees aren’t identified until they die of natural causes. In 2011, for instance, a felled oak tree with two bullets embedded in the trunk was found on Culp’s Hill in Gettysburg National Military Park in Pennsylvania. Photographs or other historic records, however, can confirm some witness trees—and rule out others—with relative ease.

Confirmed witness trees are precious. They survived trauma, and then dodged disease and storms and whatever else humans and nature have hurled at them for dozens or even hundreds of years. Though some trees can live for 500 years, it’s unknown how much longer some of these may survive.

Communing with a witness tree offers a true, one-of-a-kind thrill. “It’s a live thing,” says Joe Calzarette, Natural Resources Program Manager at Antietam National Battlefield in Maryland. “There’s something about a live thing that you can connect with in a way you can’t with an inanimate object.”

To experience it yourself, visit these five trees that have witnessed some of the most traumatic and tragic events that have shaped U.S. history. When you go, respect any barriers—natural or manmade—between you and the witness tree, and take care never to get too close to trees that seem approachable. Even walking on nearby soil can have an impact on a tree’s root system and overall health.

The War of 1812 Willow Oak, Oxon Cove Park & Oxon Hill Farm, Maryland

The blood and fire of the War of 1812 Willow Oak’s namesake hostilities reached the tree during the Battle of Bladensburg on August 24, 1814. The lonely oak with its thick, gnarled trunk now stands in a grassy field in Maryland, near the parking lot of the Oxon Cove Park & Oxon Hill Farm in Oxon Hill, known two centuries ago as Mount Welby, home of British sympathizers Dr. Samuel DeButts and his family. The tree and estate overlooked Washington, D.C.

On that August night, British troops defeated American troops about six miles away from Mount Welby, then attacked the capital, setting the White House and other parts of the city on fire. DeButts’ wife, Mary Welby, wrote of that evening: “Our house shook repeatedly by the firing upon forts [and] Bridges, [and was] illuminated by the fires in our Capital.” The DeButts family later found three rockets from the fighting on their property.

White Oak Tree, Manassas National Battlefield Park, Virginia

At the eastern edge of Manassas National Battlefield Park, walk across Bull Run Creek via Stone Bridge, take a right on the trail, then curve around the water. Ahead on the left rises a White Oak that survived not one but two Civil War battles.

The tree grows in a spot that both Union and Confederate armies thought was critical to victory. On the morning of July 21, 1861, the opening shots of the First Battle of Manassas pierced the sultry summer air over the nearby Stone Bridge, as the Union made its initial diversionary attack. When the battle ended, Union troops retreated across the bridge and through the water. Confederate troops also retreated through here on March 9, 1862, destroying the original Stone Bridge behind them as they evacuated their winter camps.

Troops from both sides returned to the tree’s orbit during the Second Battle of Manassas in late August 1862, with the defeated Union rear guard destroying a makeshift replacement wooden bridge. A photo from March 1862 by George N. Barnard shows a decimated landscape, the trees thin and bare. Today, the scene is more serene, with the tree—and a rebuilt Stone Bridge—sturdy and resolute.

The National Park Service estimates Manassas contains hundreds of other witness trees, many having been found with the help of a Girl Scout working on her Gold Award project.

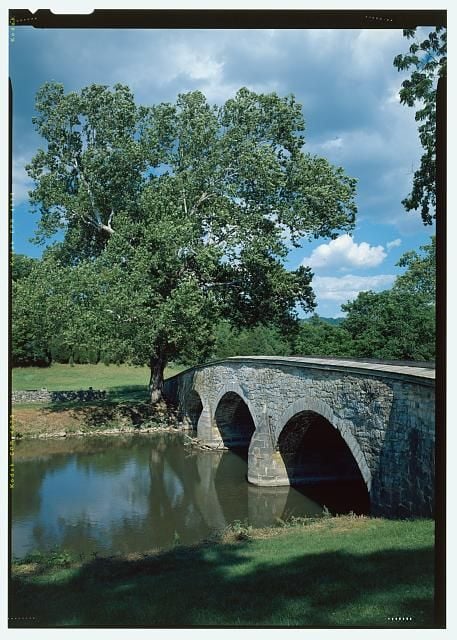

The Burnside Sycamore, Antietam National Battlefield, Maryland

During the afternoon of September 17, 1862, General Ambrose Burnside and his Union troops battled three hours against dug-in Confederate positions to cross a bridge over Antietam Creek. An additional two hours of fighting ensued against Confederate reinforcements. There were more than 600 casualties at Burnside Bridge, contributing to the Civil War’s bloodiest day.

Amid the fighting, a young sycamore growing beside the bridge withstood the crossfire. We know this because, several days later, Alexander Gardner photographed what became known as the Burnside Bridge, with the tree near the lower left corner of the image. The iconic photo can be seen at Antietam on the wayside in front of the tree, located in the southern reaches of Antietam National Battlefield.

The Burnside Sycamore has since faced other threats, like flooding and even the bridge itself. The bridge's foundation is probably limiting the tree’s root system. But now the tree stands tall and healthy, its branches spreading high above the bridge and the gentle creek, creating a serene, shady nook. “People see the tree and they see the little wayside and they think, ‘Boy, if this tree could talk,'”says Calzarette.

Antietam contains several other known witness trees, including in the West and North Woods.

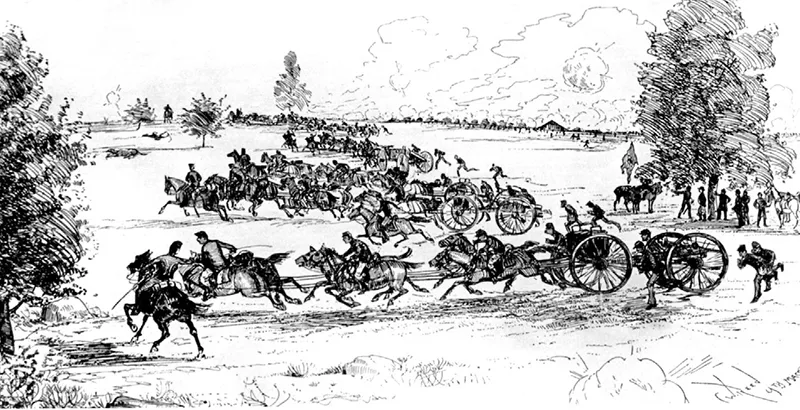

The Sickles Oak, Gettysburg National Military Park, Pennsylvania

The Swamp White Oak on the grounds of Trostle Farm witnessed some of Gettysburg’s heaviest fighting—its shade beckoned a notorious Civil War figure looking for a command post. Charles Reed sketched Major General Daniel E. Sickles and his men gathered under the Sickles Oak during the afternoon of July 2, 1863, not long before Sickles disobeyed direct orders and marched his men into disaster. During an onslaught by Confederate troops, Sickles’ men took heavy losses; Sickles lost his right leg to a cannonball.

The Sickles Oak was at least 75 years old at the time of the battle, and it’s grown into a “big, beautiful, healthy-looking tree,” says Katie Lawhon, Gettysburg National Military Park spokesperson. Several witness trees are believed to survive in Gettysburg, but the Sickles Oak is among the most accessible today. It’s close to stop 11 on the Gettysburg auto tour, near the still-standing buildings of Trostle Farm.

Oklahoma City Survivor Tree, Oklahoma City National Memorial, Oklahoma

When Timothy McVeigh bombed the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building on April 19, 1995, killing 168 people, an American elm in downtown Oklahoma City absorbed the blast. Glass and metal from the explosion embedded in its bark. The hood of an exploded car landed in its crown.

Instead of removing the tree to extract evidence, survivors, family members of those killed in the blast, and others urged officials to save the almost 100-year-old elm. Planners of the Oklahoma City National Memorial created conditions to allow the tree to recover and thrive; they also made it a focal point of the memorial. A custom promontory surrounds the 40-foot-tall tree, ensuring the elm gets proper care above and below ground. The Survivor Tree, as it’s now known, like many other witness trees, serves as a touchstone of resilience.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.