This New York City Park Was Built on Top of a Cemetery

In the late 19th century, city officials turned the final resting place for 10,000 souls into what’s now Greenwich Village’s James J. Walker Park

:focal(1512x1224:1513x1225)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/b9/34/b9341a97-6953-4080-8a20-a1fb1bbd24bc/james_j_walker_park.jpg)

James J. Walker Park in New York City’s Greenwich Village neighborhood teems with life most warm weekends. Teenagers run for position on soccer fields while couples play pickleball on a nearby court. Children clamber across playground equipment or, in the summer months, cool off in the spray shower. Adults stroll underneath tall trees and through the community garden.

It’s far less lively around the white stone monument near the park’s northern entrance. The roughly seven-by-seven-foot monument, topped with a stone replica of a coffin adorned with firefighting tools, stands as silent witness to a time when this land did not crawl with life. A sarcophagus for two young firemen killed in the line of duty in 1834, the memorial also includes a large plaque affixed to its east-facing side, which says:

“This ground was used as a cemetery by Trinity Parish during the years 1834-1898. It was made a public park by the City of New York in the year 1897-8. This monument stood in the cemetery and was removed to this spot in the year 1898.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/b0/53/b0532154-29d9-49a5-b4f1-1ade683995a7/371162593_6aa92b3229_c.jpg)

Parkgoers who pause to ponder this memorial may find themselves with more questions than answers: This park used to be a cemetery? Are bocce players on the long court bowling over burial sites? Are there graves underneath the jungle gym where those kids are climbing?

The short answer is yes.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/e6/48/e648e376-729c-46ba-a8b3-3551ab371ca6/456563989_518208523917777_2788226752711695520_n.jpg)

As uncomfortable as it may make us today, New York officials in the late 19th century apparently had few qualms about creating a park over a cemetery. At the time, they were looking for innovative ways to provide more green spaces in the city’s crowded neighborhoods, and they determined that a plot of land that had provided the final resting place for about 10,000 souls could be put to better use for its living citizens.

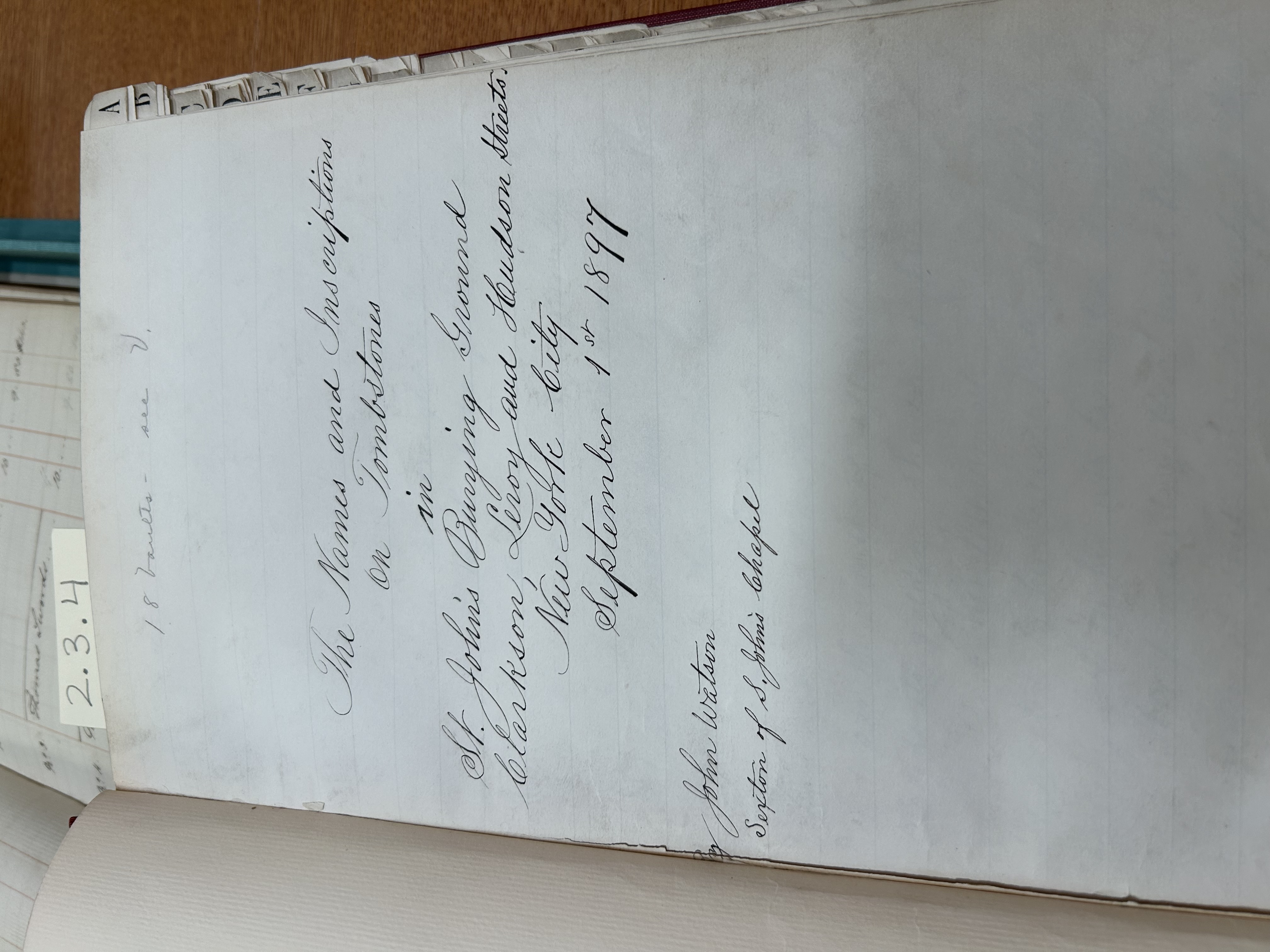

St. John’s Burying Ground, at that point, had been a cemetery for close to a century, although it is difficult to pinpoint with any accuracy when the land had accepted its first burial. Bounded by Leroy, Hudson and Clarkson Streets, the cemetery was affiliated with St. John’s Chapel (since demolished) of Trinity Parish, best known today for its historic church and burial grounds opposite Wall Street.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/1b/e8/1be8c2de-3e32-4d4e-887a-1a428cbc7746/1245px-st_johns_burial_ground_in_1854.jpg)

The plaque on the firefighter monument says the cemetery was born in 1834, while other sources suggest it existed as early as 1799. The best information is likely to come from Trinity Church, which has historically controlled multiple cemeteries in Manhattan.

“The first mention of St. John’s cemetery in our records is in December 1807,” says church archivist Kathryn Hurwitz. “However, a plan for the layout of the cemetery was not approved until March 1812.”

An 1891 article published in the New York Herald said St. John’s Burying Ground had begun “far out in the country,” but the city had quickly grown up all around it. “All Greenwich buried there, and as the city grew northward many of the most substantial of the New York businessmen in the early part of the 19th century secured lots in the cemetery.”

The Herald article also said “thousands” were placed in unmarked graves during an 1832 cholera epidemic that killed over 3,500 in a city of 250,000. The area around St. John’s Burying Ground was especially hard-hit, which led to numerous unidentified graves.

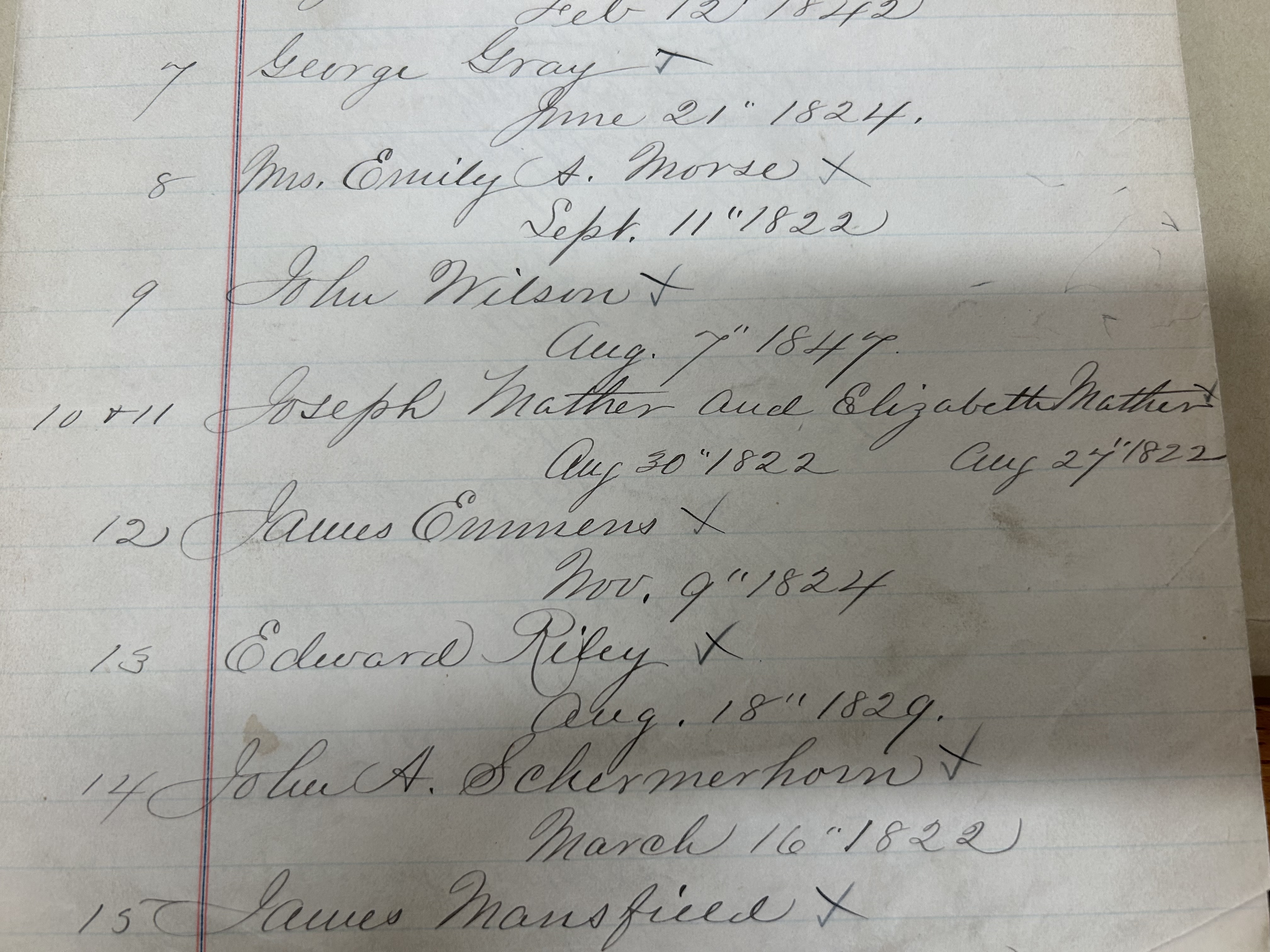

According to Trinity Church archives and other sources, St. John’s Burying Ground included members of prominent New York families, with such surnames as Roosevelt, Schermerhorn, Bayard, Mott, Lawrence and Ten Eyck. And it became the resting place of famous performers of the day, such as actress Naomi Vincent and actor, playwright, comedian and theater manager William E. Burton.

However, St. John’s Burying Ground was primarily a resting place for everyday New Yorkers, according to journalist John Flavel Mines. In his late 19th-century book Walks in Our Churchyards: Old New York, Trinity Parish, Mines wrote, “There are not many people of renown or whose memory has outlived their day and generation, buried here.” Many of the 800 grave markers in the cemetery were “rustic and quaint,” he wrote, noting that the deceased was a “calico engraver,” “bookseller,” “wife of merchant.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/a4/7a/a47a25ee-5ee3-4678-a507-337e9bcebdd8/st_johns_cemetery_1995.jpg)

But some tombstones in the cemetery were large and elaborate, featuring poems, expressions of love, and descriptions of how the end came, including “an intermittent fever” or being lost at sea. The most prominent grave marker in St. John’s Burying Ground was the one that remains: the memorial to the firefighters who were 20 and 22 when they were killed by a falling wall while they were fighting a fire. The sarcophagus supposedly contains the bones of the young men, although questions have been raised about that reality.

An 1851 New York City ordinance prohibited full-body burials south of 86th Street unless the individual was to be placed in part of a family crypt. William E. Burton’s burial in 1860 was the last recorded at St. John’s Burying Ground.

Although it was no longer receiving bodies, St. John’s Burying Ground grew to be “a picturesque place in summertime, with its fine old shade trees,” according to Moses King in his 1892 King’s Handbook of New York City. The Herald article described the cemetery as the “loveliest landmark around all Greenwich.” Edgar Allan Poe was known to wander the cemetery when he lived nearby.

But by the 1880s, the neighborhood and the cemetery had decidedly deteriorated. The 1891 Herald article stated that the Board of Street Opening had petitioned one Judge O’Brien to have it condemned. The 1891 Herald piece, which was titled “To Empty Ten Thousand Time Honored Graves; The Contest of Trinity Church to Prevent the Desecration of St. John’s Historic Churchyard,” said that the board argued that the cemetery was not “being used,” “had fallen into decay” and was “uncared for.” It declared, “There has been talk of the city taking it for a park, which is much needed in that tenement-house district.”

Trinity Parish disagreed with the Board of Street Opening’s assessment and the city’s plan, telling the newspaper that the cemetery was being cared for by a full-time “keeper.” More important, the church asserted that “no one had the right or could possibly claim the right of molesting the 10,000 bodies buried there.”

However, the city soon determined to claim the right to St. John’s Burying Ground by using the power it had gained through the 1887 Small Parks Act. This act was approved by the State Legislature, which allowed the city to create parks in crowded immigrant neighborhoods.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/56/13/5613330a-d759-4269-9157-6e1da7ad0899/gettyimages-71558380.jpg)

Trinity fought valiantly to keep the cemetery, even offering the city an alternative property that it suggested was “larger and better adapted to the purpose.” Archives of Vestry minutes from 1890 to 1896 show that the church also floated the idea of converting the property into a catacombs-style configuration, leaving caskets and graves undisturbed, and promised to keep the property in better condition to make it more “park-like” for neighborhood residents.

Citizens tried to derail the plan as well, more appalled by the idea of razing an old cemetery than delighted by the prospects of a new park. “The opposition came not only from Trinity Church,” the Herald article said, “but from hundreds of people whose ancestors have been sleeping beneath the wide spreading sycamores in some instances since 1804.”

“It is regarded as a fight against the politicians,” the Herald said, “because no one but ‘the politicians’ is credited with the scheme to disturb the bones of ten thousand of New York’s solid, old time citizens and make their present resting place a public play ground.” The article urged Trinity to carry on the fight “with as much vigor as it was against inherent sin.”

The church did keep fighting, all the way up to the New York Supreme Court, but it lost in the end. Mines lamented that the church’s loss meant the city would “tear the dead from their graves and compel the destruction of the trees that have twined their roots around the coffins and boxes of the buried thousands who sleep there.”

But maybe Mines didn’t fully understand the city’s plans, because it seems few of the dead were ever torn from their graves.

When the city gained access to St. John’s Burying Ground in 1895, it also became responsible for the 10,000 bodies in those grounds. Its first move was to transfer that responsibility to others.

City officials made public appeals in newspapers and other venues, encouraging citizens to come and get the bodies of family members they knew were buried there. They also told those families they were required to make all the arrangements and absorb all the costs for moving bodies. Few emerged to take that deal.

The city extended its own deadline for body retrieval, but even with the extra time, most sources say fewer than 200 bodies were actually relocated.

Watching in horror as the city made plans to bury the buried and raze the tombstones, Trinity in late 1897 sent John Watson, a sexton of the nearby St. John’s Chapel, to record information from the cemetery’s headstones for posterity. Watson took copious notes in two binders, recording names and dates, causes of death, sentiments, and other information engraved on the tombstones. He even sketched some of the more elaborate tombstones, working right up until the city razed the remaining markers and then covered them over with concrete.

Modern sensibilities would have a hard time accepting the city’s decision to turn a cemetery into a park, and especially of its decision to not remove the graves. However, James J. Walker Park is not the only New York City space that rose from such a past, according to Mary French, founder of the New York City Cemetery Project. Sara D. Roosevelt Park on the Lower East Side was the site of the Bethel Baptist Church cemetery, Madison Square Park was briefly used as a public burial ground in the late 1700s, and Washington Square Park was built over the graves of about 20,000 people, according to French’s website. French’s work “chronicles the graveyards” of New York City, according to the project’s website, asserting that graveyards “are the story of New York City in microcosm.” And it appears a lot of the Big Apple’s “story” includes graveyards that were wiped off the map.

But paving over cemeteries to repurpose the property eventually grew out of favor, and St. John’s Burying Ground was a dwindling example of such a transition. The initial layout of the new park, according to the official website of the New York City Department of Parks & Recreation, was led by the architecture firm Carrère and Hastings, which transformed the cemetery into an “elegant park design, which included a sunken garden, lagoon, perimeter walk and gazebo.” Little of that “elegant” design survives, as the park has been modified repeatedly to “serve the needs of its community,” according to the website.

During a 1939 modification, workers unearthed the iron coffin of Mary Elizabeth Tisdall, who died in 1850 at age 6. Trinity Church moved Mary Elizabeth to its Wall Street cemetery, so she would have a more permanent resting place.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/0d/ea/0dea9f45-6acb-4341-9ae7-166710a6e934/371161361_d6823de843_c.jpg)

Even the name of the park has changed more than once over the years. In 1945, it received its current moniker, which honors a flamboyant and controversial two-term New York City mayor who had lived in the neighborhood until his death in 1946.

Today, James J. Walker Park serves more as an outdoor recreation area than a green space. Cracked stones, broken bricks and overgrown roots require visitors to remain vigilant if they want to remain upright. Peeling paint and missing swings add to the park’s unkempt appearance. The adjoining Tony Dapolito Recreation Center has been serving the community since 1908 but closed with the 2020 Covid-19 pandemic. Currently surrounded by scaffolding and construction materials, it faces an uncertain future.

Locals enjoy what they can of this misshapen park, from having lunch on a bench under falling autumn leaves to even just using its middle pathway as a shortcut to get from one street to the next. But in true New York City fashion, most park visitors never give a thought to what lies beneath their feet.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.