This Thanksgiving, Step Back in Time and into 17th-Century Plymouth Colony

Reenactors in this “living museum” bring the Pilgrim’s homestead back to life

The year is 1627. The seven years since the Mayflower landed in Plymouth Harbor have been hard. More than half the original passengers are dead, and many survivors have endured long separations from family members left behind in the Old World. But things are looking up, the colonists will tell you. Harvests are strong, and the population is growing. And today the sun is out, and it's a fine morning to dry the laundry.

Three miles south of modern Plymouth, MA, visitors are invited to step back in time and into the 17th-Century farming and maritime community built by the Pilgrims. Although smaller than the original settlement, the Plimoth Plantation "living museum," a Smithsonian Affiliate, features authentic reproductions of thatched-roofed houses, a protective palisade, working farms and actors who have assumed the dress, speech patterns and personas of historical colonists. Visitors are encouraged to wander the "plantation" (a term used interchangeable with "colony") and ask the inhabitants about their new lives, including their complicated relationship with their neighbors, the Wampanoag.

Thanksgiving is peak season at Plimoth (the spelling William Bradford used in his famous history of the colony), but the museum makes a point to remind visitors that the true story of the "First Thanksgiving" is riddled with missing information. According to historical accounts, Massasoit, an important leader of the nearby Wampanoag village of Pokanoket, and at least 90 of his men joined the colonists for a harvest celebration in the fall of 1621. But the exact reason behind the visit and many of the details remain mysteries. The following year, tensions rose between the two groups after a handful of English settlers attempted to expand further into Wampanoag territory.

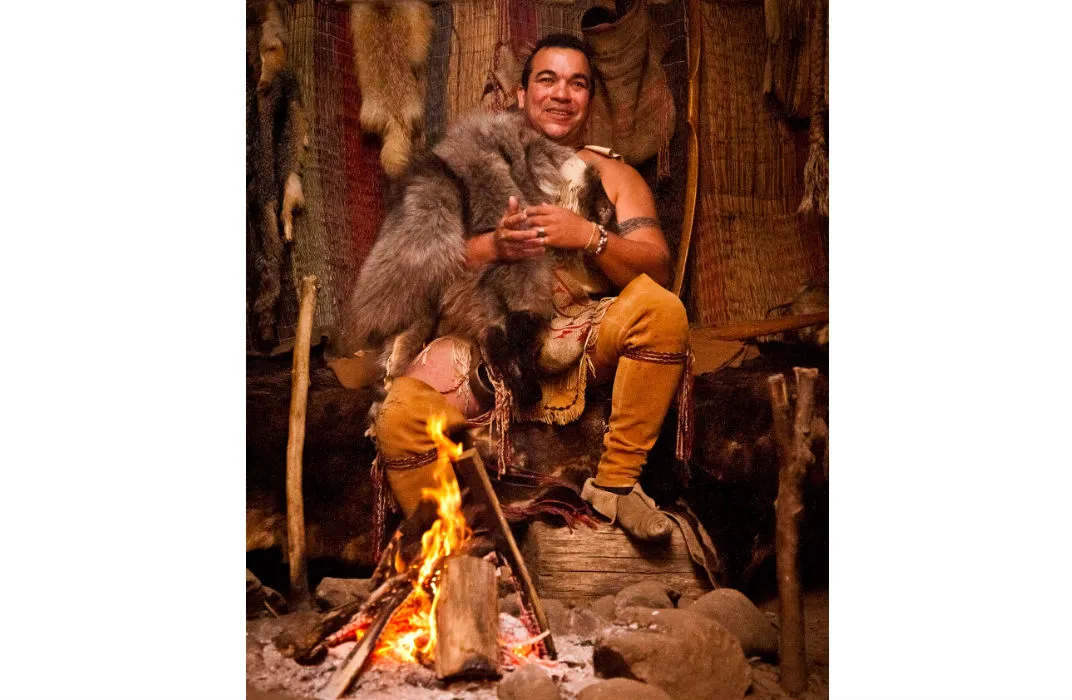

Visitors are encouraged to get additional perspectives on early Pilgrim-Wampanoag relations in the nearby Wampanoag Homesite. The village is a recreation of what the Wampanoag settlement would have looked like during the summer growing season. The staff working in the outdoor museum are all Native Americans, either Wampanoag or from other Native Nations. While their clothing and houses are contemporary to the 17th-century, the Native interpreters are not role players like in the Plimoth English Village and discuss Wampanoag history and culture with visitors from a modern perspective.

The museum is open daily from late March through the Sunday after Thanksgiving (Dec. 1, 2013).

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/0a/a1/0aa168ec-e5a0-40da-b5ab-3893ae8ff78a/plymouth2.jpg)