A Tour of Beauty Industry Pioneer Madam C.J. Walker’s Indianapolis

The hair-care magnate at the center of the new Netflix series ‘Self Made’ left her imprint on the city where she launched her career

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c8/24/c8242ff4-9a97-4bc3-adb8-e9ab318f377e/madamcjwalker.jpg)

One of America’s most prolific entrepreneurs also happens to be one of the lesser known business leaders of the early 20th century. But that could change this week when Netflix airs a miniseries in her honor. Called “Self Made: Inspired by the Life of Madam C.J. Walker,” the four-part drama starring Octavia Spencer will transport viewers back to the early 1900s when Walker, then in her late 30s, created a line of hair-care products designed specifically for black women’s hair. In the years following the launch of her business venture, she catapulted from a laundress earning less than a dollar a day to a door-to-door saleswoman for someone else’s beauty business to one of the nation’s wealthiest self-made women.

Now, nearly a century later, Walker’s legacy as an entrepreneur, activist and philanthropist (she regularly made donations to black secondary schools, colleges and organizations, including the African-American YMCA, and was instrumental in furthering the work of the NAACP) continues to be a cause for celebration and is a prime example of the true spirit of entrepreneurship.

“What she was doing through her entrepreneurial endeavors wasn’t just focused on her own economic and financial advancement, but it was a way for her to provide economic advancement for her community, particularly black working-class women,” says Crystal M. Moten, a curator in the Division of Work and Industry at the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History. “[She thought] of a way that the beauty industry could give these women financial independence and autonomy over their labor and working lives.”

Born on a Louisiana cotton plantation in 1867 as Sarah Breedlove, Walker was one of six children and the first to be born into freedom with the passage of the Emancipation Proclamation. At the age of seven, after the untimely death of both her parents due to unknown causes, Walker became an orphan and moved in with her older sister and her brother-in-law. In 1885, at the age of 18, she gave birth to her daughter, A'Lelia, whom she had with her husband, Moses McWilliams. However, when McWilliams died two years later, she and her daughter moved to Saint Louis to be closer to her brothers, who worked as barbers. She took on a job as a washerwoman at their barbershop. During that time she met Charles J. Walker, who worked in advertising, and they married. After becoming afflicted with a scalp disorder that caused her to lose her hair, Walker formulated her first hair-care product, which her husband helped advertise. Together they moved to Colorado and began marketing the product, hiring door-to-door salespeople and traveling the nation to do public demonstrations.

As the business grew, in 1910, Walker moved her business to Indianapolis, building a factory that also housed a beauty school, hair salon and a laboratory to test new products. She continued to work, splitting her time between Harlem in New York City, where she became an important advocate for the NAACP and other organizations, and Indianapolis, where lived in a two-story home located at 640 N. West St. (the home is no longer there and was replaced by an apartment complex). She died in 1919 at the age of 51, the result of hypertension.

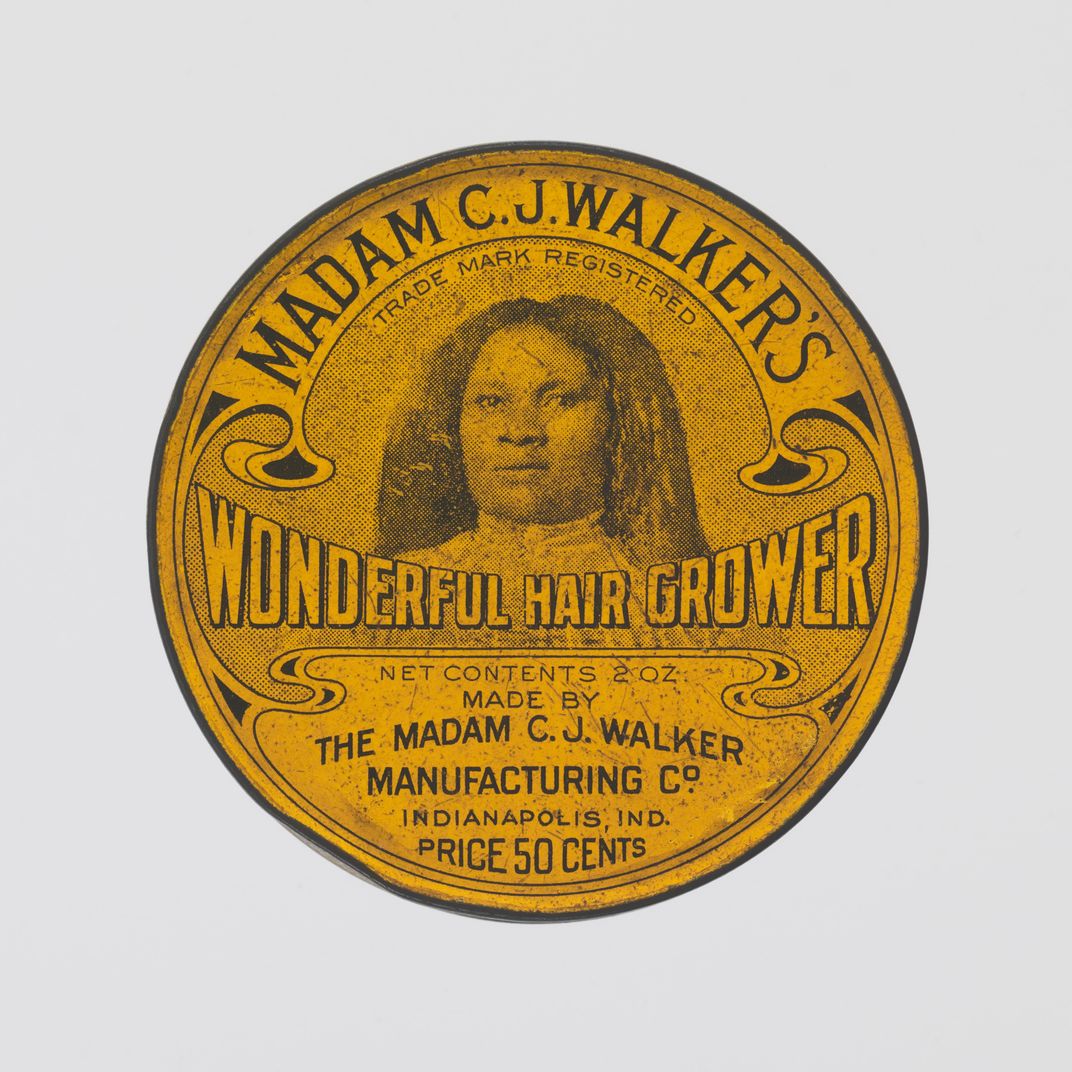

Today, more than a dozen objects in the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture’s collection are linked back to her, including a tin of Walker’s Glossine, a product intended for “beautifying and softening the hair” that also happened to be one of the Madam C.J. Walker Manufacturing Company’s top sellers. The Indiana Historical Society also holds numerous photographs, books and products pertaining to Walker in its own collection, and has an exhibition currently on view called “You Are There 1915: Madam C. J. Walker, Empowering Women.” And finally, the Lemelson Center for the Study of Invention and Innovation at the National Museum of American History houses a vast collection of Walker's belongings, including 104 manuscript boxes, seven photograph boxes and 12 bound volumes containing everything from licensed beauty manuals from her beauty school to journals and ledgers.

Janine Sherman Barrois and Elle Johnson of the Netflix series "Self Made" visit the Smithsonian on the Portraits podcast

“I think that it’s really important that her story is told today, because it offers a way for us to understand what life was like for black people in the early 20th century,” Moten says. “Race, class and gender combined to affect black people’s lives, but it also shows us what’s possible, even coming from a very humble beginning. [Walker] was able to create a business while also thinking about how to impact her community by creating a structure that had tremendous impact despite the odds that she faced. Many times we think of her as the first black woman millionaire, focusing on her financial and economic success, but what I think is more important to look at is the ways she cared about and for her community, and she was able to demonstrate that through her philanthropic activities. She’s not just a lesson in financial prowess, but also a lesson in community organizing and uplift, community development and philanthropy. We can learn so much from all of those different aspects of her story.”

“Self Made: Inspired by the Life of Madam C. J. Walker” begins streaming on Netflix on March 20. Until then, here are five important sites around Indianapolis to celebrate Walker.

Madam Walker Legacy Center

When Walker moved the Madam C.J. Walker Manufacturing Company to Indianapolis in 1910, one of her first orders of business was creating a headquarters and manufacturing facility. The multistory brick building would go on to become an important piece of Indianapolis’ architectural history and remains the only structure from that era that is still standing on the 600 block of Indiana Avenue, a roadway that cuts diagonally through the heart of the city. Now known as the Madam Walker Legacy Center, the building is listed on the National Register of Historic Places and is home to a theater that over the years has played host to music legends like Ella Fitzgerald, Nat King Cole and Lena Horne. In March, the center, which recently underwent a $15 million renovation, will reopen as a venue celebrating Walker’s legacy and will continue with her commitment to supporting the local community through cultural education, youth empowerment programs, live performances, and more.

Indiana Historical Society

Madam C.J. Walker is the focus of the Indiana Historical Society’s current installment of its popular “You Are There” exhibition series. For “You Are There 1915: Madam C.J. Walker, Empowering Women,” actors portray Walker and other individuals who played an important role in her life, including her daughter A’Lelia, who helped grow her mother’s business, along with various employees of her factory. The interactive exhibition, which runs now through January 23, 2021, features a collection of photographs and objects, such as a Christmas card that Walker sent out to her staff and tins of her famous hair products.

Madam C.J. Walker Art Installation

From the outside, The Alexander hotel in downtown Indianapolis looks like any ordinary hotel, but inside it houses a permanent art installation in the lobby that will cause you to do a double take. Created by artist Sonya Clark, the wall-sized work is made up of nearly 4,000 fine-toothed black plastic combs pieced together to form Walker’s likeness. “Combs speak to Walker’s career as a pioneer of hair care,” Clark said in an online interview. “I also used them because they capture our national legacy of hair culture, and the gender and race politics of hair. As disposable objects, they parallel the low social status of African-American women born in the late 1800s. But together, the thousands of combs become a monumental tapestry, signifying Walker’s magnitude and success despite her humble beginnings.”

Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church

After settling in Indianapolis, Walker became a member of the Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church, the city's oldest African-American congregation, which was founded in 1836 with the church being constructed in 1869. By 2016, the aging red brick building had seen better days, and the church sold it to developers. Because it’s on the National Register of Historic Places, developers have integrated the structure into the new build, which once complete later next year will be home to a new hotel’s reception area, meeting rooms and a conference hall. Developers are working closely with the Indiana Historical Society, which is providing old photos, to make sure they’re staying true to the building’s original aesthetic.

Talking Wall Art Installation

Walker is just one of the many important black historical figures featured in Talking Wall, a sculpture by artist Bernard Williams located on the Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis campus. To create the large-scale permanent art installation, Williams fused together pieces of painted steel to form a collection of symbols, including a giant fist that’s rising out of hair combs in an act of strength. He looked to African-American cultural traditions like quilting and carving as inspiration. Even the installation’s site plays an important role, as it once served as the location of Indiana Public School’s School 4, a racially segregated school for black children. In his artist’s statement, Williams says this about his artwork in general: “My critique of history and culture is often subtle. History is personally incorporated and relived. The past is never over and always beginning, altering the model of history and creating the past anew.”

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.