Tour the World’s First Nuclear Power Plant

The historic site in a remote desert is now a museum where visitors can see the instruments that made nuclear history

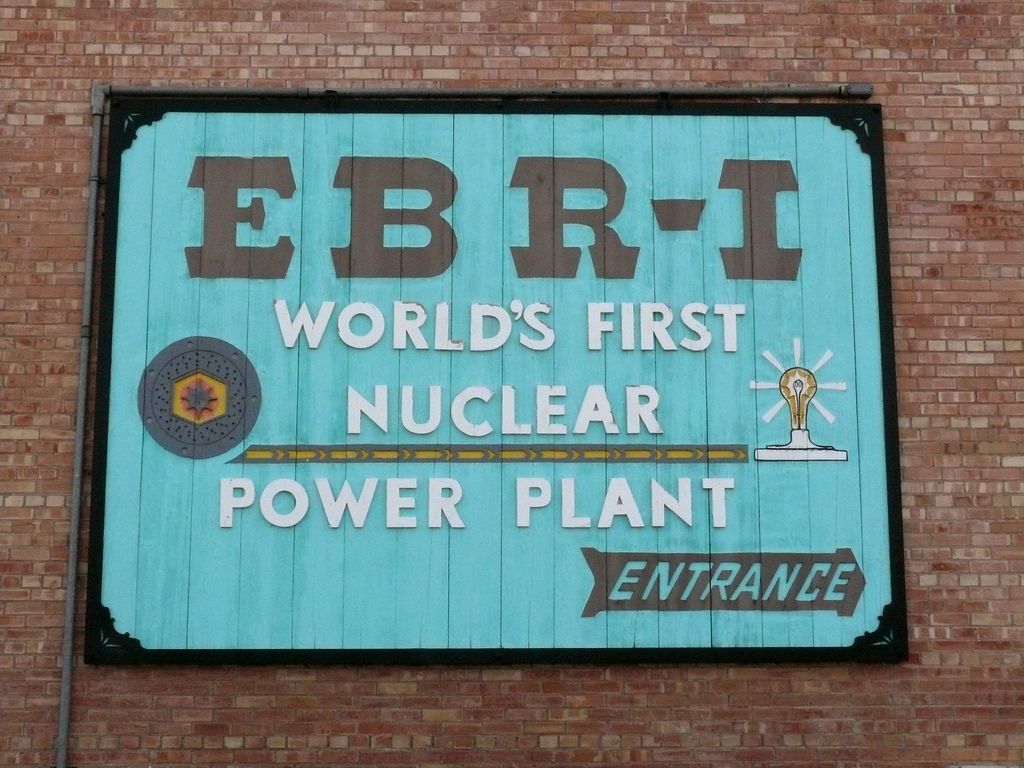

With nothing but tufts of sagebrush lining the road, it could be a normal drive through southwest Idaho. But as the car continues along the narrow strip, it enters a 900-square-mile federal testing site called the Idaho National Laboratory. The large swath of land, with almost no visible buildings, soon starts to feel like some top-secret area out of Men in Black. Where are Will Smith and Tommy Lee Jones, and where are they hiding the aliens? Eventually, the car reaches a building that’s open to the public—Experimental Breeder Reactor No. 1: the world’s first nuclear power plant, now open for tours as a museum.

The Experimental Breeder Reactor No. 1, or EBR-1 for short, made history on December 20, 1951, when it became the first plant to generate usable electricity from atomic energy. (In 1954, a facility in Obninsk, Russia, became the world’s first nuclear power plant to generate electricity for commercial use.) Since tours began in 1975, the EBR-1 Atomic Museum has let visitors go right up and touch the instruments in the reactor control room, try their hand at the mechanical arms that used to hold radioactive materials and even stand on top of where the nuclear fuel rods once plunged. The museum also provides a fascinating glimpse of the human history of the place. Open seven days a week during summer, the plant-turned-museum offers free tours, either on one’s own or with a guide.

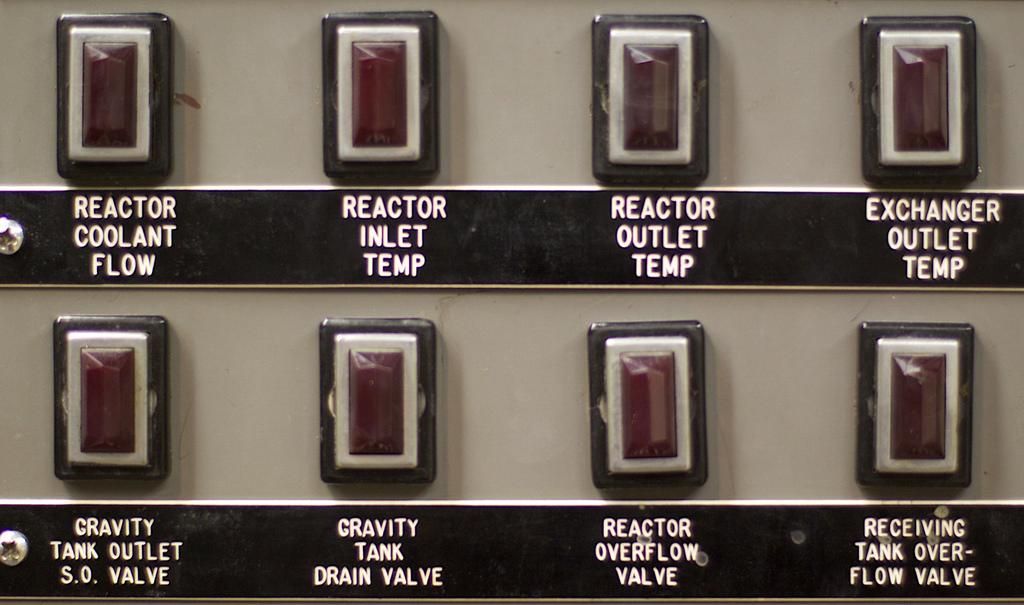

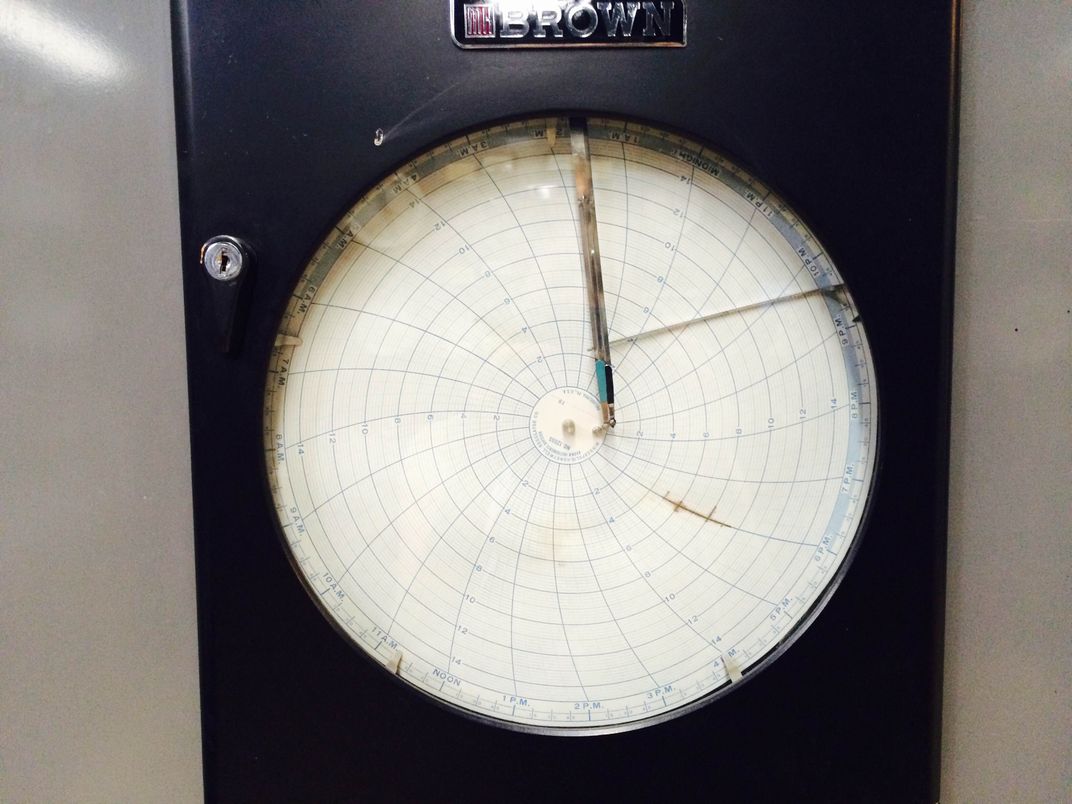

The control room harkens back to a more analog era, when instruments on the wall looked like not much more than a piece of spiral graph paper behind glass and there was a noticeable lack of computer screens. There’s also the all-important SCRAM button, for emergency shut-down of the reactor. A museum sign explains the history of the acronym, which comes from an earlier plant, Chicago Pile-1, and a rather rudimentary-sounding emergency system.

The Chicago plant is notable for being the first to reach a state in which its nuclear-fission chain reaction was self-sustaining. Despite that achievement, however, emergency precautions at the time weren't very high-tech, at least by today’s standards. Those precautions included workers suspending a thin rod of cadmium from a rope so that it dangled above a hole in the reactor. They used cadmium because it can slow down or stop a nuclear reaction by absorbing neutrons, hopefully stemming a disaster. But there was no automatic mechanism to make the cadmium fall into the hole. Instead, a museum sign explains, a “sturdy young male physicist stood by the rope, holding an axe.” (You can’t make this stuff up.) If something went wrong, he’d “swing his axe and cut the rope, plunging the rod into its hole and shutting down the reaction instantly.” That earned him the name “Safety Control Rod Axe Man,” now SCRAM for short.

It’s that kind of information—and the combination of cutting-edge technology with what that might seem quaint to us today—that makes a visit to EBR-1 special. Signs, information boards and guides explain the science of nuclear reactions for a lay audience, but visitors also get to see the human side of nuclear power’s origins. Near the entrance to the plant-turned-museum is an historic eyeglass-tissue dispenser with jaunty mid-century illustrations. “Sight Savers,” it reads, “Dow Corning Silicone Treated Tissues,” with a man’s face next to the words: “Keep your glasses clean.”

The original log book from Walter Zinn, the man in charge of EBR-1 when it was built, is also on display. The book sits opened to the page from December 20, 1951, when the reaction first produced usable electricity, showing his notes from that important day. The plant ran for 12 years after that until it was officially shut down in December 1963 and decommissioned the following year.

And in a playful twist, visitors also get to do something workers used to, only without the danger. Back in the ’50s and early ’60s, those who needed to fix or inspect radioactive items used a joystick-like apparatus to control a giant mechanical arm. The claw at the end of that arm—and the radioactive items it could pick up—stood behind a thick wall of protective glass that users could look through as they manipulated the dangerous materials. Now, instead of toxic flotsam behind the glass, the museum has laid out blocks and other props to let patrons test their dexterity, risk-free, before the long drive back through sun-bleached shrubs.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/michele-lent-hirsch.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/michele-lent-hirsch.jpg)