Tracking History Through Rainbow Bridge

Old photographs of early 20th century outdoorsmen outline the path used by hikers today seeking the American Southwest landmark

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Rainbow-Bridge-American-Southwest-631.jpg)

“My great-grandfather’s family didn’t much like the culture of the early 20th century in the West,” says Harvey Leake of John Wetherill, a well-known explorer and trader in southern Utah at the turn of the 20th century. “He didn’t believe in dominating nature, but in trying to accommodate it, and that included native peoples.”

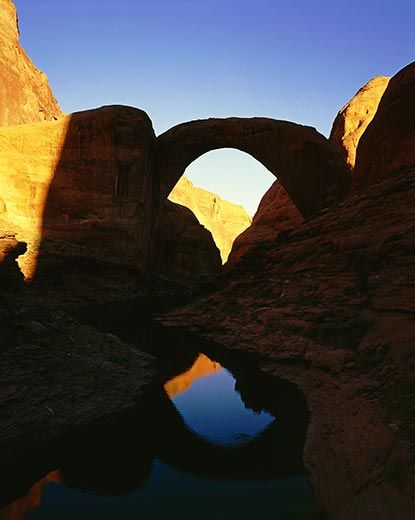

Wetherill participated in numerous expeditions into the gorgeous, forbidding slick-rock canyons above the Colorado River, often crossing the Arizona line. He and a few others are credited with the “discovery” of Rainbow Bridge, a massive natural rock formation almost 300 feet high from the base, with a span of 275 feet that is 42 feet thick at the top. One of those trips, in 1913, included former president Theodore Roosevelt.

In Pueblo cultures the bridge had been considered sacred for centuries. Wetherill’s wife, Louisa, spoke Navajo fluently and first learned of its existence; she informed her husband, whose exploits in 1909 helped bring it to the attention of the wider world. Now Rainbow Bridge attracts thousands of visitors a year because with the damming of the Colorado River in 1956 and the creation of Lake Powell, power boats can motor to within a half mile of what was once one of the most inaccessible natural wonders in the American Southwest.

Recently, Harvey Leake decided to follow his great-grandfather’s tortured 20-mile overland course in this, the centennial year of Rainbow Bridge being named a national monument by President William Howard Taft. Leake is accompanied by five other outdoor enthusiasts, myself included, and we shoulder our packs in the shadow of snow-draped Navajo Mountain at dawn, having first driven through a spring snowstorm for this 21st-century backcountry reenactment, sans horses.

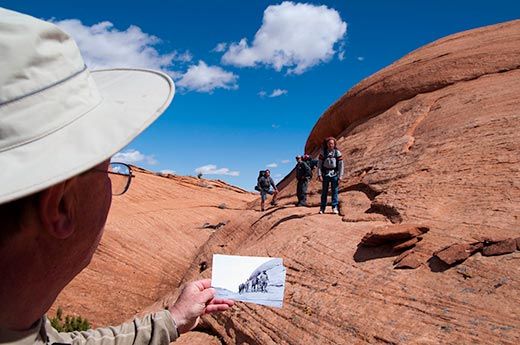

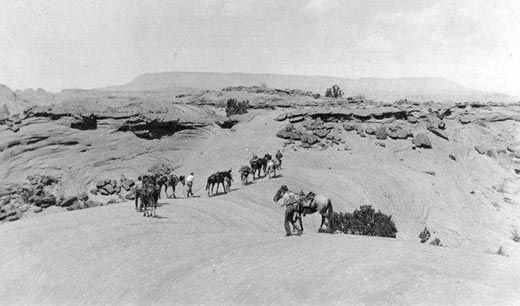

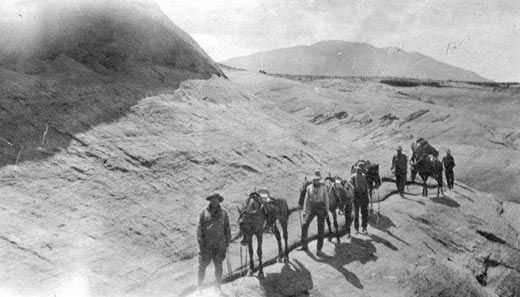

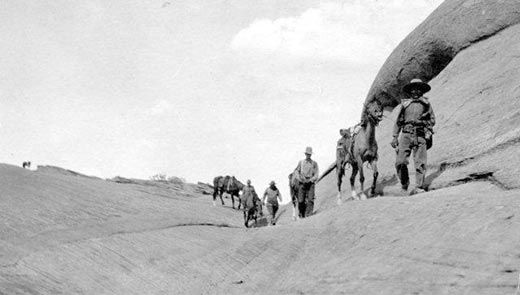

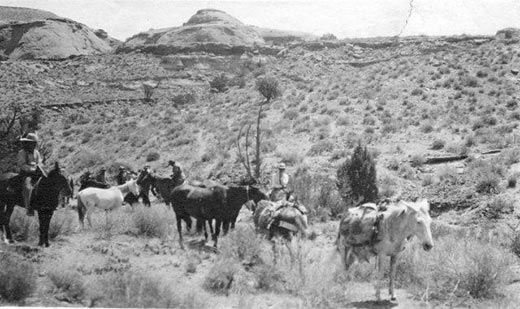

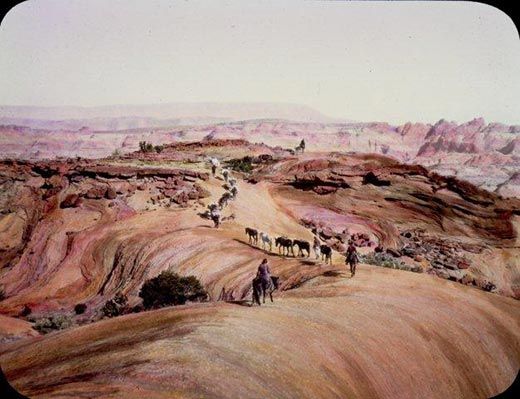

There’s no trail, but Leake has brought along a unique navigational tool—a packet of old photographs from John Wetherill’s early expeditions. These black-and-whites will be matched with surrounding horizons and are full of vast arid country sprinkled with a verdant grass called Mormon tea, wind-and-water sculpted sandstone monoliths—an up-ended, deeply shadowed world of hanging caverns a thousand feet above many drainages we climb into and out of.

I’m jealous of the men in saddles, with their big hats and boots. In one photo, Wetherill looks the unassuming cowboy, but his Paiute guide, Nasja Begay, wears a properly dour expression. Roosevelt, a famous outdoorsman, solidly sits his mount wearing dusty jodhpurs, cloth wrappings on his lower legs as protection against the cacti and yucca spines, and his signature rimless specs.

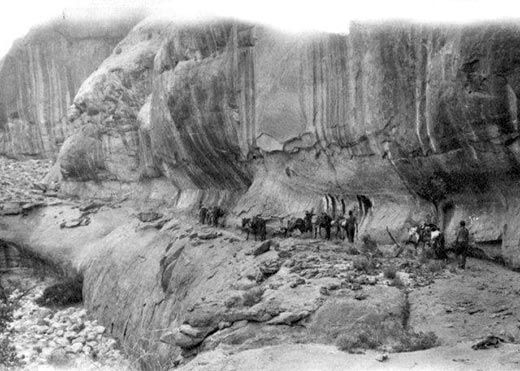

What the photographs don’t show is the astonishing chromatic vibrancy of this living sandstone diorama, its striated walls resembling hieroglyphics carved by natural forces, accentuated by the blue-greens of twisted conifers and stunted gambel oaks. The dark, almost purplish streaks of iron that have leached out of Navajo sandstone are known as “desert varnish” and glow in the powerful sunlight.

We pass a long-abandoned Hogan—a conical dwelling with the doorway facing east, made of dried-up grass, twisted juniper logs and mud—that was probably used by a sheep herder in the distant past. We stop to consult the photos, comparing horizon lines and landmarks. Everyone has an opinion about which way to go, but Harvey will once again prove to be the surer navigator.

“Here’s where they had to dismount,” he says, holding aloft a photo of the steep slick-rock slope we’re standing on. “They had to lead the horses down from this point.” Exactly how is a mystery, but Leake is unconcerned. Here’s what the former president and Rough Rider had to say about the same scene: “On we went, under the pitiless sun, through a contorted wilderness of scalped peaks… and along tilted masses of sheet-rock ending in cliffs. At the foot of one of these lay the bleached skeleton of a horse.”

The rest of us decide to lower our packs by rope into a crevice and clamber after them, squeezing between rock walls until we’ve gained access to more or less level ground. And there’s Leake, who had found his great-grandfather’s more circuitous route, and beaten us to the bottom.

Surprise Valley is a lovely corridor of colored stone, junipers and sandy soil untouched by discernible footprints other than those of mule deer and an occasional wild stallion. We set up camp, 12 miles and as many hours into the 20-mile hike to Rainbow Bridge, exhausted. The others build a fire, but I’m in my sleeping bag shortly after dark, and the next morning feeling the effects of cold and altitude. Kerrick James, our photographer, offers me a cup of hot Sierra tea, the best thing I’ve ever tasted.

About eight hours and several drainages later we are descending Bridge Creek when the National Park Service interpreter on the trip, Chuck Smith, says, “Look over your left shoulder.” There, partially obscured by a canyon wall, is the upper thrust of Rainbow Bridge, even its colossal grandeur diminished by the towering rock walls above it.

Almost an hour later we get there, weary but exhilarated. The bridge is the remnant of a massive fin of Navajo sandstone laid down some 200 million years ago by inland seas and violent winds. It blocked the flow of the creek until the water worked its way through the permeable rock, and the wind over eons widened the hole and added height to the span in the process. The base is of harder Kayenta sandstone, older and darker, a beautiful reddish brown contrast with the lighter rock above.

Other notables of a century ago passed this way, including the famous novelist Zane Grey, who pitched his tent next to a juniper like the one still standing at the bridge’s base. The various Wetherill parties did the same, but today, camping is not allowed near the bridge, still considered a religious site. And no one is allowed on top—although to gain access would require several more hours of climbing canyon walls to the east, now touched with the sort of light that inspired Grey’s purplest prose.

“Teddy floated under the bridge,” says Smith, an ambulatory encyclopedia of Rainbow Bridge information and the foremost advocate of this unique place. “On his back, looking up. I’ll bet he said, ‘Bully.’ ”

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.