Even by the wild standards of the Pacific Northwest, Minam River Lodge is remote. After driving 280 miles east from Portland, I followed a series of ever-narrowing back roads to the lonely farming hamlet of Cove, where cellphone and GPS reception disappeared. The lodge staff had warned me to print out the directions beforehand, so I located “Forest Lane 6220,” a steep, washboard gravel road broken by cattle guards that climbs eight miles up to the trailhead, 5,510 feet above sea level in the Wallowa Mountains. This was where the real adventure began. At a weathered wooden sign—“Horse Ranch Trail 1908”—I laced up my hiking boots, hoisted my pack and set off into the shadowy forest, fighting the vague sense that I might disappear forever. But the unease vanished when the trees parted to reveal an alpine meadow framed by verdant mountains and distant snowcapped peaks, all beneath polished blue skies—the lavish beauty of Oregon distilled.

In the course of the afternoon, I descended 2,000 feet into the Eagle Cap Wilderness, one of the largest natural refuges in the lower 48 states. Its 360,000 acres contain 31 peaks over 8,000 feet, 60 alpine lakes and vast expanses of fir, larch and limber pine. From high ridges, the Minam, one of the most pristine rivers in Oregon, could be heard burbling far below. At other times, the forest fell into silence until a wind rustled through the branches. A sign with tiny scratched text offered hikers encouragement: “½ Way There!”

At last, I spotted the lodge, a collection of wood cabins and canvas tents nestled on the valley floor. It was built on the footprint of a dude ranch that opened in 1951, and at first it seemed that not much had changed since those days. Three dogs loped past, while a wrangler in a broad Spanish hat and chaps saddled a horse. Putting down my pack, I was greeted by a bearded figure in a red flannel shirt who looked like a lumberjack from a Jack London story. He turned out to be the chef, Sean Temple, who gleefully declared: “You’re in luck! Tonight we have quail!” He added that he had an organic sauvignon blanc that would pair well.

The Minam River Lodge epitomizes Oregon’s quirky creativity. It offers all the classic outdoor activities that have been popular in the West for generations, such as hiking, swimming and horseback riding. But it has also become famous for its fine food. That night at dinner, Temple quieted the 20 or so seated guests and stood for a speech. “Day 95 of the season!” he announced—and rattled off a menu that I almost needed a gastronomic dictionary to follow: wood-fired, herb marinated quail, house-made sourdough and chicken liver mousse, garden greens in a nectarine and rosé vinaigrette, braised chard with anchovy, garlic, lemongrass and oregano, and roasted acorn squash garnished with spruce tips and pine pollen. It was a dizzying end to a day on the trails, complementing the otherworldly setting. After the meal, I retired to the campfire for a more traditional Western pursuit, nursing a glass of whiskey and counting shooting stars.

* * *

Back in the Gilded Age, the lush and misty Pacific Northwest was untouched by the first great currents of U.S. travel, when Arizona was dubbed “the Italy of America” and Colorado “the Switzerland of America,” and the New England coast was lined with European-style resorts that employed chefs shipped in from Paris. Long after the railway reached Portland in 1883, the region kept its pioneer flavor, and the rugged hinterland was left to loggers, gold miners and ranchers. Nature was bountiful in Oregon, but it was there as an expendable resource.

It was only in the 1910s that automobile touring and the wilderness movement began to put Oregon on the travel map for the same reason it had been avoided before: raw, untrammeled wilderness. The language that had once been used by economic boosters to praise the state’s natural resources now attracted sightseers. Still, tourism got off to a slow start: In 1913, the state had only 25 miles of paved roads. In the Great Depression, though, the Works Progress Administration (WPA) funded an ambitious string of projects, including scenic roadways, hiking trails and mountain refuges, with the aim of giving Americans access to healthful recreation. Many Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) works remain the basis of travel in the most popular corners of Oregon today.

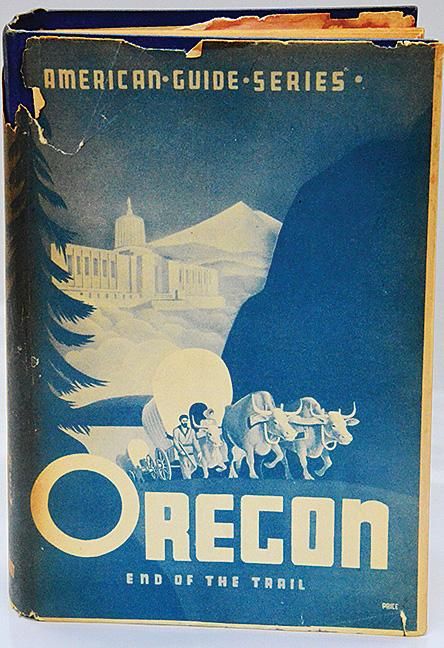

Those engineering feats in the Pacific Northwest had their counterpart in the WPA guidebook series. It was a national project of massive ambition: From the mid-1930s, an army of 6,500 writers, including Saul Bellow, Ralph Ellison and Zora Neale Hurston, fanned out across the country to pen a volume for every state. Historians have observed that the guidebooks were part of a larger quest to define a shared American culture and “way of life,” making travel nothing less than “an adventure in national rediscovery.” John Steinbeck called the WPA guides “the most comprehensive account of the United States ever got together” and dreamed (in vain) of packing all 48 in his baggage for the American road trip described in his 1962 book, Travels With Charley.

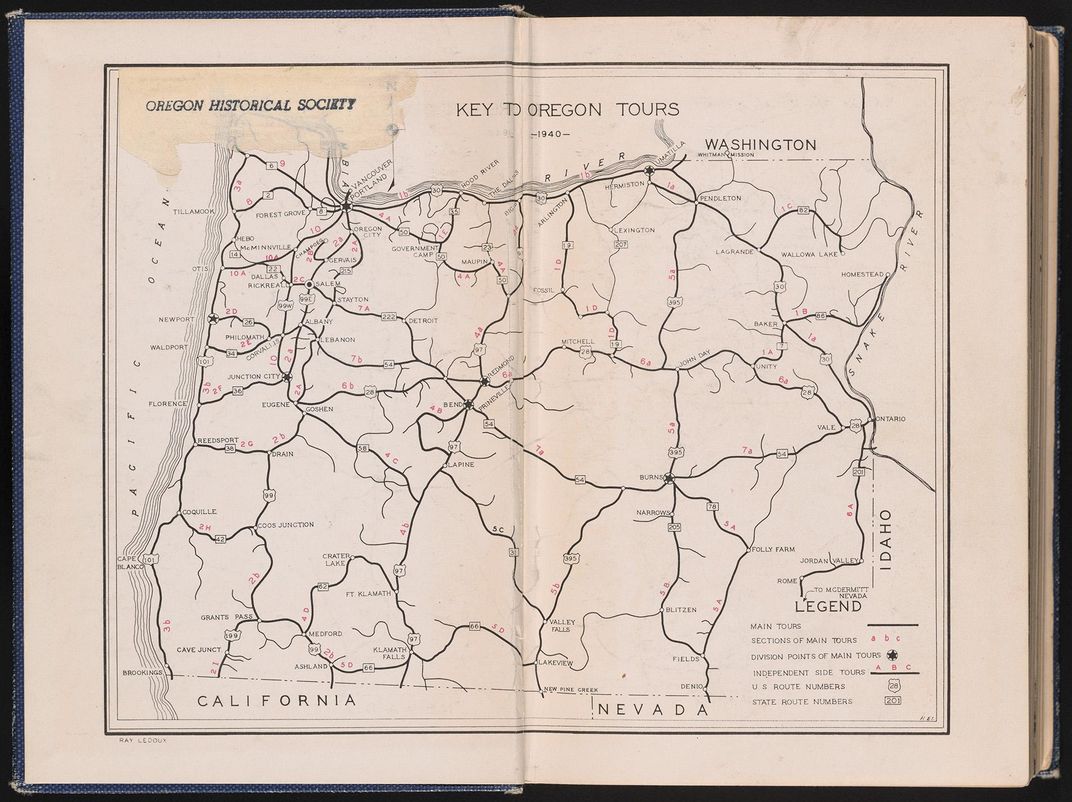

The WPA series gave Oregon its due as a destination for the first time. The 550-page volume, subtitled “The End of the Trail,” was among the last WPA guidebooks to be published, in 1940, but it covered the state’s attractions in encyclopedic detail, with ten classic road trips broken down into 35 mini-tours. The prose is not quite Steinbeck’s standards, but it is filled with wry humor. The editor T.J. Edmonds wrote that when the subtitle “The Beaver State” was suggested, local wits complained: “Why not call it the Rodent State so as not to discriminate against our rabbits and prairie dogs?” The tome includes recipes for huckleberry cakes and venison, and an explanation of why Oregonians call themselves “web-foots” (for the notorious rainy winters). Although Americans had only around 18 months to use it before Pearl Harbor, the guidebook enjoyed a new spell of utility after the war, when returning G.I.s sought out Oregon’s wild places as a balm to civilization’s ills.

Seventy-five years later, I could sympathize. I had spent six months in lockdown in Manhattan during the pandemic, and as U.S. travel slowly reopened, nature was high on my mind. I had heard about the Minam River Lodge from an outdoors-loving friend, and planned a two-week road-trip around a state that seemed a self-contained world filled with alluring secrets. In September of last year, it would be an understatement to say that it was a unique historical moment for travel. The flight from New York was a fraught exercise in juggling face masks and hand sanitizer. I landed in Portland, whose downtown was still boarded up in the wake of Black Lives Matter protests and police clashes that had seized international headlines since late May. And a string of wildfires had begun in western Oregon that would soon become the worst in U.S. history, cutting off many highways, closing national parks and engulfing the state in smoke.

But such calamities were hard to imagine when I first arrived in Portland, a famously livable city of quiet riverside parks, outdoor cafés and extensive bike lanes. In 1940, the WPA guidebook authors noted, slightly tongue-in-cheek, that the compact outpost was dubbed “The Athens of the West” for its cultural vibrancy, at least compared with the rest of Oregon. Following the WPA guide, I tracked down Erickson’s Saloon, a legendary complex that once served 300 loggers at a time along its 674-foot mahogany bar, and whose upstairs rooms earned it the nickname Temple of 10,000 Delights. (It had recently been turned into condos.) A few other saloons too seedy to make it into the WPA guide remain, including the Oregon Oyster Company and the White Eagle Saloon from 1905, where sailors were shanghaied.

With news about the wildfires along the coast growing dire—the noonday sun had become an orange ball, and the scent of ashes hung in the air—I rented a car and headed east along the Columbia River Highway, staying one day ahead of the smoke as it rolled in behind me.

The skies were still flawless when I hiked the next afternoon to the Minam River Lodge, which is in many ways a barometer of 21st-century American travel. The setting is as spectacular as it was in photographs from the 1950s, when a nearby valley was so dense with elk, deer and other game that it was called Mert’s Meat Locker after one of its hunting guides. From the porch, I watched the last golden rays of sun creep across a meadow where horses still gamboled. Oregonians have fine-tuned the old outdoor pleasures. There is a wood-fired hot tub nestled on a ridge—“the sweetest bath west of the Mississippi,” one guest declared—and a wood-fired sauna that can be used for leaping in and out of the near-freezing water of the Little Minam River. (“You get used to it on the fourth time!” another guest advised me.) In the wood-floored barn, a survival from the 1950s, a yoga instructor from Texas held classes every morning.

That golden dusk was my last glimpse of the mountains. When I woke up the next morning, wildfire smoke had shrouded the valley. Poring over my WPA guide, I realized that it listed another “dude outfit” in the Minam River Valley in 1940. “Oh, that must be Red’s,” said the manager, Anna Kraft. “There are a couple of volunteer caretakers taking care of it now.”

Dating to 1918, Red’s heyday came after the Second World War, when it was run by a bearded, flame-haired former firefighter from Portland named Ralph “Red” Higgins. A larger-than-life raconteur and bon vivant, Red lured outdoors-loving celebrities to hunt and fish, including, according to unshakable local lore, John Wayne, Lee Marvin and Burt Lancaster as well as, a local author proudly noted, “the entire Los Angeles Rams football team.” Red’s Falstaffian tenure ended with his death in 1970; in the mid-1990s, the ranch was sold to the Forest Service, which planned to level the site until it was saved by a public outcry.

I was greeted by one of the volunteers, Cynder Spath, who had just arrived on horseback with her husband, Jeff; the two previous caretakers, Mike and Mona Rahn, were also still in residence, waiting for the smoke to lift. The unpaid position on a one- to two-week rotation was so desirable among Oregonian nature-lovers, mostly retirees, that there was a years-long waiting list, they said, even though the ranch had no electricity or phone, and only propane gas for cooking. The setting was magical, with cabins handcrafted from knotty pine nestled by a shady pebble “beach” on the Little Minam. Shooing away wild turkeys, Jeff Spath showed me around the 30-plus structures. The main building, erected in 1946, was still intact, its interior decorated with a bear skin, elk antlers and a wagon wheel chandelier. But the cabins were in serious decay. Their river rock floors had settled, and chinks in the walls let in rain and snow. Stone chimneys were leaking; one cabin had nearly been crushed by a falling tree.

It was a melancholy sight, and we contemplated the probability that much of the ranch will soon vanish, even though volunteers have offered to do repairs. “It’s just too bad,” Spath sighed. “These cabins would be beautiful if there was a little upkeep. Instead, they’ve been left to their own demise.” Its eccentric Oregonian past only made the loss seem more poignant. Mike Rahn, whose uncle had been one of Red’s carpenters, showed me the ranch’s most offbeat attraction: a concrete step where guests would engrave their signatures in a backwoods version of the Hollywood Walk of Fame. One was “Goldwyn,” possibly Samuel, the illustrious MGM producer, or his son.

“Burt Lancaster’s signature used to be there,” Rahn sighed, “but someone broke it off and stole it.”

* * *

What other American sagas lay hidden in the Wallowa Mountains? Once I had ascended the 2,000 feet of trail back to my car—riding in the packhorse train with the wrangler to avoid choking on wildfire smoke—I consulted the WPA guidebook again. The volume provides a window onto a period when Oregon was still regarded by most as a half-fantastical frontier. Indeed, the editor Edmonds had anticipated its historical value, with a self-awareness rare among travel authors: In the future, he wrote loftily, it “will serve as a reference source well-thumbed by school children and cherished by scholars, as a treasure trove of history, a picture of a period, and as a fadeless film of a civilization.” What he did not anticipate was that our view of the America it describes would not be purely nostalgic.

In fact, Oregon is grappling with an unusually bleak racial history. The state has a liberal reputation today, but in the 19th century its white settlers attempted to extirpate almost any nonwhite population and create a Jim Crow system that lasted well into the 20th century. Written by progressive authors, the WPA guide was ahead of its time by at least attempting to include alternative views. But it was penned before the civil rights era, and today its value as a document is as much what it leaves out as what it includes.

My new mission in the Oregon heartland was to fill in the gaps. And it seemed that everywhere I went, once-forgotten stories are emerging back into the light.

The logical base for exploration was the town of Joseph, a former logging outpost near the shores of Wallowa Lake, a dazzling ribbon of crystalline water surrounded by glacial moraines. Like the Minam River Lodge, the town is today an easygoing mix of Old and New West. Sitting outside an elegant café called the Blythe Cricket, I watched a cowboy in a ten-gallon hat ride up, tether his horse by the window and order a double soy latte. At the Jennings Hotel, the foot-worn wooden entrance stairway felt like something from the The Shining or Deadwood, but a handwritten poem was posted on one banister. (Titled “Things to Remember,” it includes: “prairies, forest, thunder...wild rose, alpenglow...rocks tumbling in the surf...the Alamo...”) The 1910 landmark hotel was restored in 2015 with a Kickstarter campaign, and its rooms individually designed by Portland artists. The building also now includes a boutique with a BLM sign in the window and a gourmet pizza restaurant. “Eastern Oregon is very conservative, but also libertarian. It’s live and let live. The old-timers were just happy I was fixing the place up. It was falling to bits,” says the owner Greg Hennes.

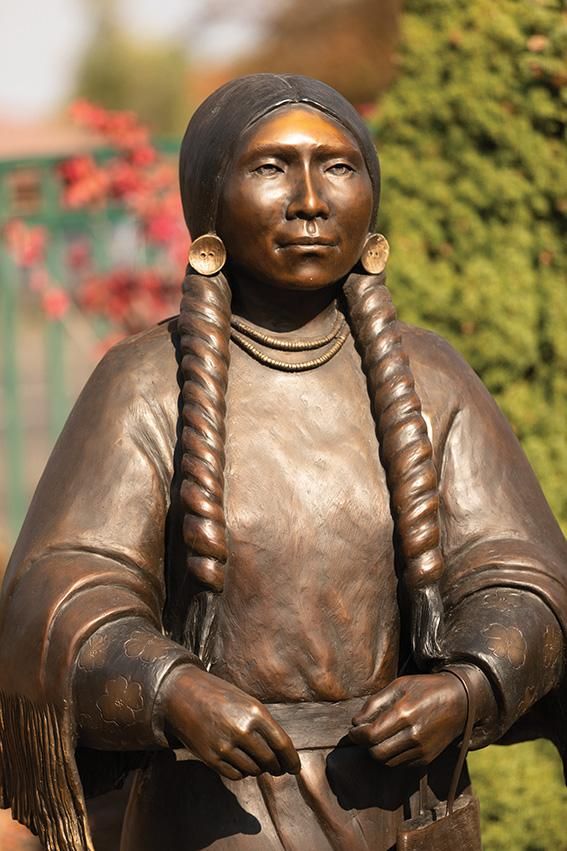

Pioneers moved in the 1850s to this fertile lakeside, which for centuries had been the crown jewel of the Nez Perce Indians’ ancestral homelands in the Wallowa Mountains. The town’s name commemorates Chief Joseph, the tribe’s brilliant leader (called “the Red Napoleon”), who refused to accept the so-called “thieves treaty” of 1863, imposed by the U.S. government to take away the tribe’s land and devastate its nomadic lifestyle and religion. When the Army arrived to enforce the treaty in the summer of 1877, Joseph led some 700 Nez Perce men, women and children on a grueling 1,170-mile flight across Idaho and Montana and portions of Wyoming, including a detour through the newly declared Yellowstone National Park. Outwitting his cavalry pursuers over and again, Joseph (whose real name was Hinmató·wyalahtq’it) and 418 surviving followers were forced to surrender only 40 miles from safety at the Canadian border. Chief Joseph’s heroic resistance and dignified pronouncements earned him the admiration of both the military and the American public. Though the settlers named the town after him, as well as a nearby mountain, a creek and a canyon, the gestures were empty. When Joseph returned—twice—to ask for a parcel of land so he and his closest relatives could grow old in his beloved home, 200 citizens signed a petition against it. He died in 1904 on the Colville Reservation in Washington State, the most famous Native American in the United States, and one of the most tragic.

By the time of the WPA guide, the Wallowa Valley and its surrounds had become renowned as a scenic wonder. “From their slopes flow a number of streams that have cut deep, rock-walled canyons, and plunge over ledges in long ribbons. Glacial meadows are tapestried with brightly colored wild flowers,” the guide says. The Nez Perce, banished to reservations in Idaho and Washington State, were by then rarely seen. Few in 1940 could have imagined that they would return to their valley; at the time, many believed that Native Americans would slowly die out. Which is why one of the region’s most interesting new attractions is the Nez Perce Wallowa Homeland project, a unique blend of nature park and cultural site that is fulfilling Chief Joseph’s dream of a base for the tribe in their traditional lands.

The town of Wallowa was hit hard by closures and workforce reductions at sawmills in the 1980s and ’90s; located a half-hour’s drive from Joseph, it feels as though tumbleweeds should be blowing down its sleepy main street. But the Homeland, on its outskirts, has a hopeful air. I wandered its parklike grounds, which lie between a spectacular basalt ridge called Tick Hill and a lush river, and visited tepees, a longhouse, a stables and a dance arbor; bronze plaques paid tribute to Indian culture. In a field, a dugout canoe was being carved by a Nez Perce craftsman. A canoe completed here in 2019 was the first Indian canoe to ply the sacred waters of Lake Wallowa since Joseph was expelled 142 years before.

“The Homeland project was born of necessity,” said Joseph Otto McCormack, one of only three members of the Nez Perce tribe who today live year-round in the valley. A former Marine and Vietnam veteran who sported a long silver handlebar mustache and goatee and a baseball cap, he arrived in a pickup truck with five friendly dogs.

When the collapse of the logging industry gutted the region’s economy in the 1980s, McCormack said, the time also felt ripe for racial reconciliation. Wallowa held an annual rodeo, Chief Joseph Days, but it had devolved into a week of evening bar brawls and tensions between white residents and Nez Perce members, who arrived from distant reservations. So in 1989, a coalition of individuals created a potluck and powwow to be held the following year at a local high school. There were displays of Indian dancing and drumming and members prepared traditional meals of elk, salmon and buffalo for the whole community. Attendees brought side dishes to share, and it was such a success that it expanded outdoors within two years. In 1998 it became known as the Tamkaliks Celebration, which added horse processions and was soon attracting 1,500 people.

Overnight, Chief Joseph’s vision of a permanent home in their summer hunting grounds was within grasp. To secure funding, the local U.S. Park Service agent Paul Henderson attended a 1993 meeting of the Oregon Trail Coordinating Council, which was promoting the 150th anniversary of the pioneer route. “I pointed out that the Oregon Trail came into Oregon, but there was also one that left: the Nez Perce Trail,” Henderson said. The foundation gave $250,000 from the sale of souvenir license plates to the Homeland project, enough for the Nez Perce to buy 160 acres. Soon after, a U.S. Department of Agriculture grant helped double the acreage. A grant from the Myer Memorial Trust funded the building of their first structure, the dance arbor.

It wasn’t all a Hollywood-worthy tale of racial healing, McCormack said. “The first person we tried to buy land from pulled it off the market because he thought it was an Indian group.” (The Homeland’s board is 50 percent Nez Perce and 50 percent “non-tribal.”) But relations with “the old Indian fighters” improved in the mid-1990s when tribal members offered to help restore steelhead and salmon to local rivers. At first, McCormack had been worried about gaining access to the rivers. “We didn’t want to have an altercation. The police attended to protect the Indians. But we were greeted by a potluck dinner and a lot of warm hearts. They said they’d love to have Indians fishing in the river, and when could they fish it themselves?” The program was a success. “It brought hope to a lot of people.” Today, tribal members work with the Fisheries Department all over their old lands; in 2019, they were given land at the head of Wallowa Lake on the river to promote the sockeye salmon there.

“It’s a huge shift in one generation,” said Angela Bombaci, the executive director of the Nez Perce Wallowa Homeland project, who grew up in Wallowa town. “It’s not cowboys versus Indians anymore. We really need to unite. The issues are bigger now.” The 2020 wildfires have added to the urgency. As the scale of the conflagration grew, Indian activists argued that they should be allowed to steward Western forests again with the controlled burning that for centuries before white settlement had prevented “mega-fires.” Bombaci and others are optimistic about the future. “The whole Indian story is a miracle of survival,” noted a Homeland board member, Rich Wandschneider. “And the Nez Perce story is now the American odyssey.”

* * *

Something about this remote corner of Oregon keeps hopeful memories alive. This is quite an achievement given the state’s grim racial history, starting with its very inception. The first white settlers declared they were building a non-slave state, but Exclusion Laws also banned African Americans from living there. One law, passed in 1844, threatened any freed slave with a lashing every six months until he or she left. Although this savage legal provision was never enforced, when Oregon joined the Union in 1859, the state constitution prohibited black people from moving there. For years Oregon’s Jim Crow laws were the most severe outside the South, with the few black residents denied the right to vote, own real estate or enter legal contracts.

Chinese gold miners were also harassed mercilessly in the late 19th century, and occasionally massacred. Life grew so bad in the town of Pendleton, for example, the Asian community moved into underground chambers and tunnels, leaving a unique ghost town that can be visited to this day. But by the 1920s, African Americans were the main targets. The Ku Klux Klan was resurgent around Oregon, and some “sundown towns” set up billboards warning: “Do Not Let the Sun Catch You.” In Portland, many businesses hung signs even in the Eisenhower era: “We Cater to White Trade Only.”

But today, attention is being given to an extraordinary exception to the grim narrative: The logging camp of Maxville, a lonely settlement 39 miles from Joseph in the Wallowa Mountains, resisted Oregon’s racist current, and from 1923 until the late 1930s flourished by becoming more integrated. The story is now being retold by one of the black loggers’ daughters, Gwendolyn Trice, who formed a nonprofit in 2008 and set up a small museum in Joseph called the Maxville Heritage Interpretive Center in 2012, and succeeded in 2020 to reclaim the original campsite to set up her own version of the Nez Perce homeland.

I discovered the unlikely story when I found the small museum one afternoon. Wearing a weathered straw cowboy hat and bright floral vintage skirt, Trice welcomed me at the door, saying “Come on in!” Hanging in pride of place on the wall inside was a grainy sepia photograph from the 1920s, which showed a team of African American loggers dressed in overalls with enormous saws over their shoulders, posing alongside white workers in a mountain forest. Another picture showed a half-dozen black and white children sitting together with their teacher in a field of cabins. Both were scenes that would have seemed like science fiction elsewhere in the state.

The logging camp, Trice explained, sprang up seemingly overnight in 1923, when a railroad was carved into the wilderness and houses were shipped in on boxcars. Defying the Exclusion Laws, which were on Oregon’s books until 1927, the Bowman-Hicks Lumber Company hired some 60 skilled black loggers from the South, including her father, 19-year-old Lafayette “Lucky” Trice of Arkansas.

Maxville was officially a segregated township, with two housing districts, two baseball teams and two schools. But the racial division quickly eroded. “It was a big fail!” Trice said with a laugh. “People were connected in many different ways. They worked alongside one another. They had to rely on one another. The families saw each other every day. People became friends. I’m a descendant of that failure!” The anomaly drew the attention of the local chapter of the Klan: “A posse came to Maxville to try to get rid of the black loggers, but the white superintendent de-hooded the leader. He said: ‘Get out, you are not welcome here. We know who you are.’” Barriers were also broken down by Maxville’s extreme isolation, especially during the bitter winters. “You live close to nature here. It’s not man pitted against man. It’s like in war, you have to work together.”

The Great Depression ended this unique social experiment, and in 1933 most of Maxville’s houses were put back on boxcars and shipped out. Soon the camp had all but vanished. But Lucky Trice stayed on in the nearby town of La Grande, where Gwendolyn grew up as the second youngest of his six children. She was almost always the only black student in her school year, but otherwise had a childhood typical of rural Oregon of that time, she says, listening to Johnny Cash and Glen Campbell, riding horses and fishing with her father. In 1977, she moved to Seattle where she worked for Boeing and as an actor, screenwriter and video producer. Her father died in 1985 without ever talking about his early life in Maxville. Trice began learning about her father being a logger in 2003 and started the process of moving back in 2005, where she began piecing it together by interviewing the camp’s elderly white residents, many of whom had been children in Maxville and still lived nearby.

She brought her research to Oregon Public Broadcasting, which featured her efforts in a documentary and allowed her to reach a wider audience. In 2015, the nonprofit foundation was given the camp’s lone surviving structure, the company headquarters, by the new landowners. A November 2020 grant from the Meyer Memorial Trust’s Justice Oregon for Black Lives, an initiative to invest in long-term strategic change in the state, along with the Maxville Heritage Interpretive Center’s ongoing fundraising efforts, should allow for the purchase of the 240 acres of Maxville and surrounds by the end of the year.

“Let’s take a gander!” Trice suggested. Soon we were driving north of Joseph onto an unpaved service road, while logging trucks roared past and a startled elk looked on. The site itself is now overgrown and reforested, but she conjured its heyday in the 1920s as a thriving camp of 400 people, and walked its long-vanished streets using a map “reconstructed from the memory of the elders.” While much was left to the imagination, not everything had disappeared. We stepped over an old water pump, the remains of the machinery workshop, and the four-acre town dump. A few miles away on private land stands the last of Maxville’s wooden railroad trestle bridges, still spanning a gully.

The sun was setting as we stood by a pond that is part of the property, watching blue herons pick their way across a carpet of white lilies. If all goes well, the log lodge that served as the original Maxville company HQ, which was documented, then taken apart and put in storage, will begin to be reconstructed on site by the 100th anniversary of Maxville in 2023 with funds from Oregon’s Cultural Advocacy Coalition. The grounds will also serve as a field school for archaeology and education hub and tour site. The regeneration of the lakeside and river areas will proceed in partnership with Nez Perce tribes.

As we drove back to Joseph, Trice offered a personal perspective on the WPA guidebook to Oregon. She said it should be read today alongside the famous Negro Motorist Green-Book, the guide written for African Americans. The reality is that in 1940, black travelers in Oregon would not even have been served at most gas stations or restaurants, and usually had to sleep in their cars. Even in the early 1960s, black travelers stopped at her father’s home in La Grande. “I remember as a little girl there would be a knock on the door in the middle of the night,” Trice said. Her father would go talk to black people who were driving through and tell them where they could stay with a family or a friendly place to buy food and gas.

By then, the racial balance in Oregon had already started to shift, with the tiny African American population swelled by shipbuilders who went to Portland during World War II and remained. The 1964 Civil Rights Act changed the legal landscape, Trice said, and the BLM movement provides the latest nudge. “When I arrived here 20 years ago, nobody was interested in the Maxville story. People acted afraid of the color of my skin. But now we’ve got a museum in the middle of Joseph and we’re loved! In summer, we get hundreds of visitors every month.” She laughed: “America is changing, doggonit!”

* * *

For the week I had been traveling around Wallowa Lake, wildfire smoke ensured that its fabled mountain scenery was barely visible. But back in Portland, the winds changed and blue skies opened. For a reminder of the state’s grandeur, Lisa Lipton, the director of Opera Theater Oregon, offered to take me to one of the city’s most theatrical natural settings, near downtown along the Columbia River Highway. The Vista House, an Art Nouveau structure perched on a promontory once known as Thor’s Heights, was built in 1915 as a pit stop for the first American road-trippers to enjoy views of the river framed by cliffs and peaks. “It’s like an opera set, only outdoors,” Lipton said, summing up much of Oregon’s spectacular landscape. “I’m thinking Wagner, maybe Tristan and Isolde.”

The highway engineer Samuel Lancaster declared in 1915 that he had designed Vista House as an “observatory” where mortals could pause “in silent communion with the infinite”—in short, a temple to Nature. He had also dedicated it to the pioneers of the Oregon Trail and the hardships they had endured. Today it’s clear that other cultures also undertook painful journeys. The future looks promising: As more historical stories come to light, 21st-century travelers will find it only natural to explore the rich and complex human past that is entwined with Oregon’s lavish scenic beauty.

Editor's Note, May 12, 2021: An earlier version of this story incorrectly listed John Steinbeck as a writer of the WPA Guides.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/be/c0/bec0f5ed-ce3d-482c-82a5-2ec784151c50/opener_mobile.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9f/ef/9fef8585-2fad-40e3-a3e4-81af006cfde6/oregon_opener_v2.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tony.png)