Twice Charmed by Portland, Oregon

The Pacific Northwest city captivated the author first when she was an adventure-seeking adolescent and again as an adult

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/My-Town-Portland-631.jpg)

Portland and I have both changed over the decades, but this city hooked me back when I was a book-drunk adolescent with a yen for stories and adventure. This is the town I ran away to, and half a century later that skewed fascination still shapes my perception of the place.

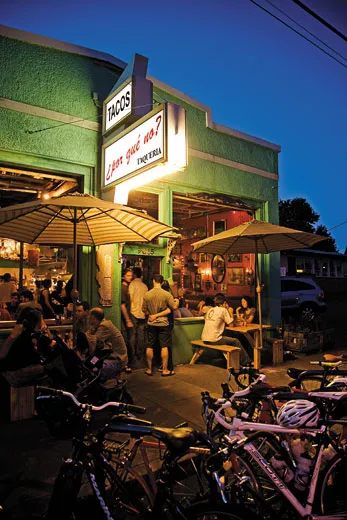

These days Portland is liberal and green. We have recycling, mass transit, bicycles, high-tech industries and so many creative types that the brewpubs and espresso shops have to work overtime to fuel them. It’s still far from perfect. But despite the familiar urban problems, there’s a goofy, energetic optimism afoot. A popular bumper sticker reads, “Keep Portland Weird,” and a lot of us try to live up to it.

Back in the early 1960s I was going to high school in a pleasant two-stoplight village some 20 miles to the west. Portland, with its population of 370,000 people, was considered fearsome and wild. Folks from small towns and farms tend to see the only big town in the state as a paved jungle of noise, danger and depravity. That’s what intrigued me.

Weekends and after school I’d hop the bus into town feeling jubilant and a tad scared. To my young eyes Portland was a tough blue-collar town, scarred by labor clashes and hard on minorities. Supported by timber and crops, built around the railhead and the river port, the city was still recovering from the Great Depression and the closing of its shipyards after World War II. Families were moving to the suburbs.

Downtown was the older, densely built west bank of the Willamette River. It climbed toward the high, forested ridge known as the West Hills, where the rich had built mansions with amazing views. The seedy section nearest the river was my early stomping ground. Taverns and strip joints were off limits at my age, but there were pawnshops, pool halls, tattoo parlors and palm readers. There were 24-hour diners and cluttered bookstores where you could hole up out of the rain and read while your sneakers dried.

I saw things, both sweet and grim, that I’d only read about. There were drunks passed out in doorways, but Romany (Gypsy) families dressed in gleaming satin picnicked in the park. I was lucky. People were kind or ignored me entirely.

A Chinese grocer suggested pork rinds as chumming bait, and I would dangle a hook and line off a storm drain near the flour mill. I watched gulls swoop around battered freighters loading cargo for the Pacific voyage, and I pulled heavy, metallic-gold carp out of the river. Mrs. M., a tarot and tea leaf specialist who lived and worked in a storefront near Burnside Street, bought them for a quarter each. She always wanted what she called “trash fish” to stew for her cats.

My first city job was trying to sell magazine subscriptions over the phone after school. Four of us blotchy teens worked in a cramped, airless room in the Romanesque Dekum Building on SW Third Avenue. Our spiels came from smeared mimeographs taped to the wall in front of us. The boss wore suspenders, Brylcreemed his hair and dropped in occasionally to deliver pep talks.

I didn’t make a single sale the first week. But I was looking forward to a paycheck when I ran up four flights of stairs on Friday afternoon, opened the office door and found it empty. Stripped. No phones, desks or people. Just a torn copy of the sales pitch crumpled in a corner. This was a stunner, but given my allegiance to Raymond Chandler and the noir flavor of the Dekum in those days, it was fitting.

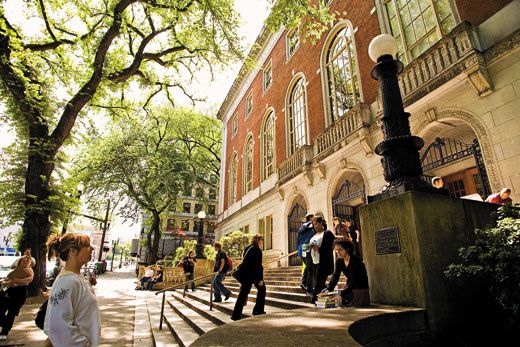

Other layers of the city gradually revealed themselves to me, and in retrospect it’s clear that the seeds of today’s Portland were well established even then. The big Central Library was the loveliest building I’d ever set foot in. I’ve seen the Parthenon and other wonders since, but that library, with its graceful central staircase, tall windows and taller ceilings, still sets off a tuning fork in my chest.

One summer I gave up shoes for philosophical reasons that escape me now, and went barefoot everywhere. I was exploring a student-infested neighborhood behind the Museum Art School and Portland State College. It had blocks of old workers’ cottages with half-finished sculptures on sagging porches, drafting tables visible through front windows, and the sound of saxophones drifting through a screen door. I was busy soaking in this bohemian air when I stepped on a broken bottle and gashed my left big toe.

I limped along, rather proud of this heroic wound and its blood trail, until a curly-haired man called me up to his porch. He scolded me with neon-charged profanity while he cleaned and bandaged the cut. He said he wrote articles for newspapers and magazines. He was the first writer I’d ever met, so I told him I wanted to write, too. He snorted and said, “Take my advice, kid. Go home and run a nice hot bath, climb in and slit your wrists. It’ll get you further.” Many years later, we met again, and laughed about the encounter.

I went to college in Portland and met people from other places who saw the city with fresh eyes, calling attention to things I’d accepted without a thought.

“Rains a lot,” some transplant might say.

Yes, it rains.

“Everything’s so green. A lot of trees here.”

Well sure, this is a rain forest.

“Drivers don’t use their horns, here.”

They do in an emergency.

“If one more store clerk tells me to have a nice day, I’ll throttle him.”

We’re polite here. Just say “thanks,” or “you too,” and you’re fine.

I’d focused on what made the city different from rural, small-town life. The newcomers reminded me that not all cities are alike. In 1967 I left Portland for other places, urban and rural, and on different continents. A decade passed and my son was ready to start school. I’d been missing the rain, and the Portland of my memory was an easy place to live, so we came back.

Portland’s population has mushroomed since I was a kid. The perpetual tug of war between preserving and modernizing saws back and forth. Urban renewal ripped out communities and poured in glass, steel and concrete, but some of the replacements are wonderful. The town is better-humored now, more easygoing. That feel of the old hobnobbing with the new is more amiable. Of course the blood and bones of the place never change—the river, the hills, the trees and the rain.

Mount Hood still floats 50 miles to the east, a daytime moon, ghostly or sharp depending on the weather. It’s been 200 years since Hood’s last big eruption. But when Mount St. Helens blew her top in May of 1980, I walked two blocks up the hill from my house and got a clear view of it spewing its fiery innards into the sky. Volcanic ash fell like gray snow on Portland and took months to wash away.

People who come here from elsewhere bring good things with them. When I was young, exotic fare meant chop suey or pizza. Students from New York City begged their parents to ship frozen bagels out by air. Now restaurants offer cuisines from all over the world.

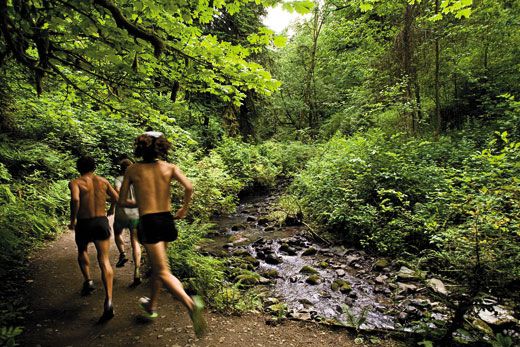

Many of my neighbors love being close to hiking and rafting, skiing and surfing. But the steep miles of trails through the trees and ferns and streams of the city’s 5,000-acre Forest Park are wilderness enough for me. I love standing on the sidewalk and looking up at clouds wrapping the tall firs in a silver wash like a Japanese ink drawing.

The weather here is not out to kill you. Summers and winters are generally mild. Sunlight comes in at a long angle, touching everything with that golden Edward Hopper light. No one loves the sun more than Portlanders. Café tables spill onto the sidewalks and fill with loungers at the first glimpse of blue sky.

But the rain is soft, and I suspect it fosters creativity. Although Portland harbors doers and makers, inventors and scholars, athletes and brilliant gardeners, what touches me most is that this town has become a haven for artists of every discipline. They are reared here, or they come from far away for mysterious reasons. Their work makes life in Portland richer and more exciting. Several theater companies offer full seasons of plays. If you’re not up for the opera, ballet or symphony, you can find stand-up comedy or dance and concert clubs in every musical genre. Animators and moviemakers burst out with festivals several times a year. Most surprising to me are the clothes designers who bring an annual fashion week to a town best known for plaid flannel and Birkenstocks.

Rain or shine, it’s just a 15-minute stroll from my door to that beautiful library, and after all this time every step of the way has layers of history for me. The oddest thing is that I’ve grown old over the past half century while Portland seems brighter, more vital and younger than ever.

Katherine Dunn’s third novel, Geek Love, was a National Book Award finalist, and her most recent book, One Ring Circus, is a collection of her boxing essays.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.