Half of the Inhabitants of This Australian Opal Capital Live Underground

Unearth Coober Pedy, the Outback’s hidden city

The Australian town of Coober Pedy looks like something straight out of a movie—probably because it is. In 1985, Mel Gibson, Tina Turner and a team of filmmakers descended onto this barren mining town in the South Australian Outback to shoot Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome. The otherworldly landscape, which is checkered with ruddy-colored mounds of sandstone—the result of years of opal mining—was the perfect backdrop for the post-apocalyptic movie. That very landscape, not to mention the lure of finding a pricey opal, has drawn people here for years. It’s also forced the town’s residents underground—literally.

“People come here to see things differently,” Robert Coro, managing director of the Desert Cave Hotel in Coober Pedy, tells Smithsonian.com. Parts of his hotel are located below the ground, like many other buildings in town. “It’s that kind of adventure mentality that attracts people here in the first place.”

Nothing about Coober Pedy is for the faint of heart. For starters, it’s hot—really hot. In the summer temperatures can creep up to 113 degrees in the shade, assuming you can find a tree large enough to stand under. Before the city passed a tree-planting initiative encouraging residents to plant seeds around town, its tallest tree was a sculpture built from scraps of metal. Even grass is considered a commodity in Coober Pedy, where the local (dirt) golf course provides golfers with squares of carpet for their tees.

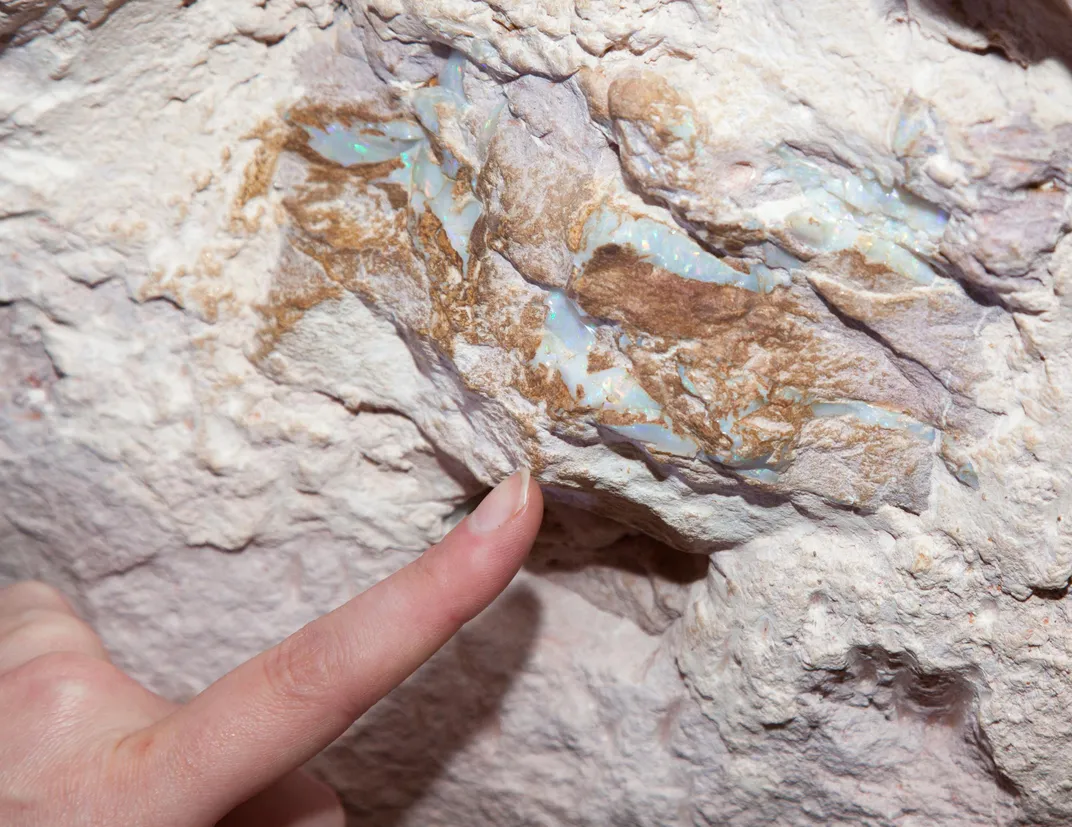

Since its founding 100 years ago after a teenager discovered opal gemstones there, the town has been ground zero for opal mining. An estimated 70 percent of the world’s opal production can be linked back to the town, earning it the title of Opal Capital of the World, and the majority of its 3,500 residents work in the opal industry. One of the latest finds was a set of opalized pearls dating back more than 65 million years—but the city offers other kinds of buried treasure, too.

Rather than move to a cooler locale, the town’s earliest residents learned to adapt to the hellish environment. They found inspiration on the very ground they stood on: Using mining tools, hardy prospectors did what they did best and dug holes into the hillsides to make underground dwellings or “dugouts.” Today about half of the population lives in dugouts where the temperature stays at a constant 75 degrees year round.

Seeking relief from the heat—and the desert’s chilly winter nights—the townsfolk continued building underground. The result is a subterranean community that includes underground museums like the Umoona Opal Mine & Museum, a sprawling former opal mine located alongside the town’s main drag, and churches like the Serbian Orthodox Church, whose sandstone walls are decorated with intricate carvings of saints. Many of the local watering holes and half of the Desert Cave Hotel’s rooms sit underground, letting guests experience the strange peace of life beneath the surface.

“The beauty of living underground is that it’s very quiet and very still,” Coro says. “There’s no air movement or rush of air from the air conditioner, and since there are no windows or natural light, you get a very peaceful night’s sleep.”

Over the years, Coober Pedy’s residents have become extremely adept at building their own dwellings underground, too, creating customized subterranean houses that go beyond just one or two rooms into sprawling labyrinths that stretch out like spiders’ webs.

“People will carve out their own bookshelves into the sandstone walls,” Michelle Provatidis, the mayor of Coober Pedy and owner of Michelle’s Opals Australia, a jewelry shop, tells Smithsonian.com. “I even know someone who has an underground swimming pool in her home.”

But it’s not just what’s going on beneath the surface that makes Coober Pedy so unique. Above ground, there are hints of the city’s strong mining roots and eccentricities around every turn. For instance, at the Coober Pedy Drive-in Theatre, the management requests that guests leave their explosives at home, while signs around town warn people to beware of unmarked holes, the remnants of previous opal digs. There’s also the annual Coober Pedy Opal Festival, which this year will be held on March 26.

Even the thin veil of red dust that settles on roadways, cars and buildings serves as a constant reminder of Coober Pedy’s strange charm. There really is no other place like it on—or below—Earth.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d2/3a/d23aacf0-311f-406c-8d92-771a8d8b15bf/42-44660231.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e7/9b/e79b87f8-55f9-4820-8439-eb5f2a3efd5e/42-58017954.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d6/34/d634d1b3-e443-4523-b043-4e8c20ebdc56/42-58025248.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ae/8e/ae8e650d-81bf-4103-b234-d7b8a1570c73/42-58025573.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/bc/48/bc48a034-eb47-41ba-b398-d256922b0161/sa006240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d9/30/d93006dc-4a8d-4e1d-930d-4bd961af9e87/sa006154.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/27/08/27083209-a2cf-460b-a0dd-131709c67bae/2730307953_3d3a6e0d3b_b.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/62/1d/621da349-8679-4e06-b438-499d6769f8c5/42-45292343.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/14/3e/143e4417-87dd-4f85-8a7d-2185d977a5ac/42-58024448.jpg)