I first learned about cichlids when I was a boy, shopping to fill an aquarium. I’d wanted a saltwater tank, because its inhabitants tend to be so much more colorful, but my parents nixed that idea as too demanding. I was getting ready to resign myself to boring guppies, plastic plants and a catfish sucking algae on the glass when the man at the aquarium shop showed me the cichlids. They came from a freshwater lake, he said, but they were as colorful as the residents of any coral reef. I paid a few dollars for a pair of electric yellow Labidochromis caeruleus, and so began my fascination with an animal that would have amazed Darwin if only he’d known about it.

Cichlids are found all over the world, mainly in Africa and Latin America, but they’re especially abundant in Lake Malawi, where they’ve diverged into at least 850 species. That’s more species of fish than can be found in all of the freshwater bodies of Europe combined.

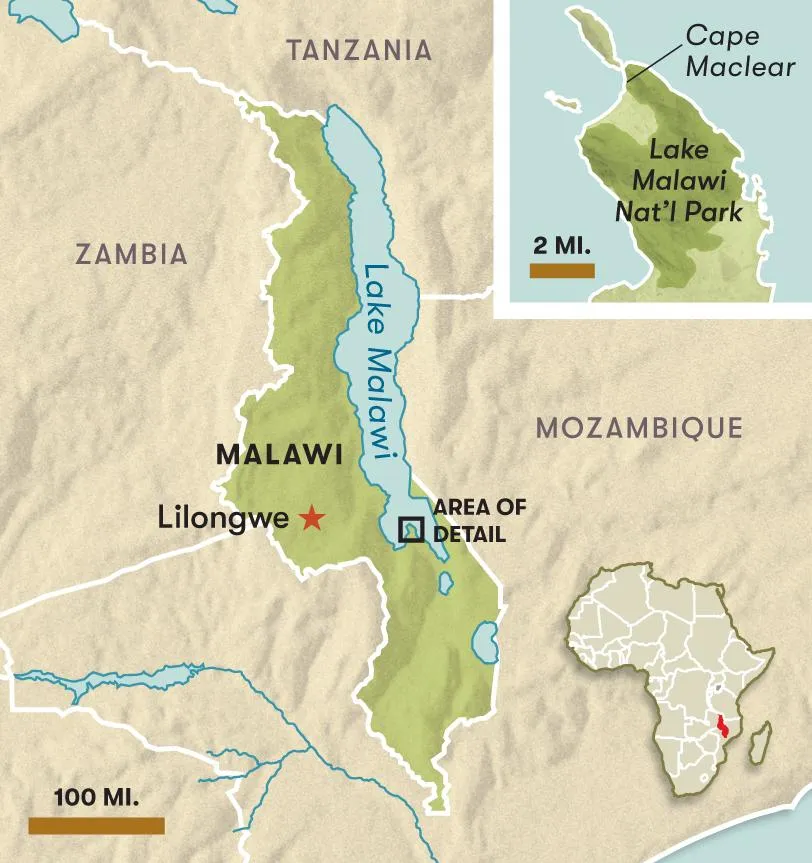

Though my interest in fishkeeping lasted only a few years, the allure of Lake Malawi never faded for me, and last September I finally made the journey to what is arguably the planet’s most vibrant body of freshwater. Malawi is a tiny landlocked country wedged between Zambia, Tanzania and Mozambique. The Great Rift Valley runs through the country lengthwise and Lake Malawi lies to one side of it, covering most of the country’s eastern border. I was going to meet Jay Stauffer Jr., a Penn State ichthyologist and one of the most respected cichlid experts in the world. Stauffer himself has discovered more than 60 new cichlid species in Lake Malawi, and his work is far from finished.

“About half the species in the lake still haven’t been described,” Stauffer told me when he and his driver, Jacobi, picked me up at my hotel in the capital city of Lilongwe. Stauffer wore a Penn State T-shirt tucked into cargo pants and spoke with a slow drawl. He has been visiting Malawi on and off for more than 30 years, and as we rode in a Land Rover to the lakeshore he told me about his four bouts of malaria and the local putzi flies, whose maggots burrow beneath human skin. This was the arid season, though, which meant fewer mosquitoes and other airborne terrors. Dry riverbeds scarred the landscape, and parched clay and wilted grass scabbed over the fields. The roads out of Lilongwe were lined with stalls, where women sold potatoes from meager rafts of shade.

After three hours, we arrived at the home of Stauffer’s friends Tony and Maria, a Portuguese couple whose patio offered my first view of the lake. The water was as blue as any Caribbean idyll, and a small domed island 100 yards offshore appeared to float like a scoop of sherbet. Lake Malawi is what’s known as a meromictic lake: Its distinct water layers—generally three—don’t mix. This provides more environments for plants and animals to live in, and it also accounts for the lake’s stunning color; sediments stay on the bottom and the top layer is crystal clear. I was keen to swim out to the island and see the fish, but Stauffer pointed to a pair of periscoping eyeballs just offshore—a hippo, one of the most aggressive animals on the continent. I stayed on the patio, where Tony poured a round of gin and tonics even though it was not yet noon.

That hippo was the only large mammal I saw in Malawi. Lions, rhinos, elephants and zebras roamed the game parks, but they did not interest me. My safari would be completely underwater, but even so there would be astonishing variety. Some cichlid species squat in empty snail shells and others roam the depths. There are pike-size predatory cichlids and perch-like algae-grazing cichlids; cichlids that school to feed on plankton; cichlids that sift through sand for insects; cichlids that steal eggs from other cichlids; and cichlids that pluck the scales off other fish.

My first eyeful came at Cape Maclear, a sandy beach popular with backpackers in Lake Malawi National Park. I rented a kayak from a lodge called the Funky Cichlid and paddled to West Thumbi Island, an uninhabited lump of boulders and barren trees. Looking over the side of my kayak through the pristine water was like staring up into a sky full of runaway balloons. The cichlids shimmered beneath the surface—black and white, silver and gold, an occasional orange and every shade of blue. I put on my snorkel and slid into the lake to discover that these blots of color were, when seen up close, elaborately patterned. Many of the blue fish were zebra striped, while one of the yellow varieties had horizontal streaks of black and white. The rocky lakebed was like a collapsed cathedral. The cichlids, mostly two to six inches long, hovered over the boulders and dashed in and out of the crevices.

These were the rock-dwelling haplochromines, Lake Malawi’s most famous cichlid group (known as mbuna, or “rockfish,” in the local Tonga language), and also the group with the greatest number of species—at least 295 and counting. Every island and stretch of rocky coastline had its own assortment of mbuna species, many of which you would find nowhere else in the lake. Even ankle-deep water was saturated with different varieties of small, colorful fish.

The Scottish explorer and missionary David Livingstone first told Europeans about Lake Malawi in 1859—the same year Charles Darwin published his revolutionary On the Origin of Species. Darwin famously formulated his theory of natural selection after observing the 14 different species of finches in the Galápagos Islands, among other phenomena. He theorized that the birds had evolved into different species because they’d been isolated in different habitats and adapted to different types of food. On one island, finches with thick beaks had outperformed thin-beaked neighbors at crunching seeds. On another island, finches with thin, pointy beaks had won out in the competition for insects. In each case, Darwin suggested, a bird with the physical advantage was able to survive longer and produce more offspring than run-of-the-mill birds, and the trait was passed down through the generations and amplified over millions of years. He called this process natural selection to contrast it with the artificial selection performed by an animal or plant breeder working to strengthen a pedigree or create a new hybrid.

If that’s the usual understanding of Darwinian evolution, the myriad cichlids of Lake Malawi pose a real challenge to it. Some 850 species have descended from the original cichlids that swam into the lake one or two million years ago. This extraordinary diversity has long puzzled evolutionary biologists, especially because, unlike the Galápagos finches, the cichlid species aren’t necessarily separated by geographical barriers. Many of them live together in the same populations, where nothing in the environment prevents them from mixing with one another. Different species of mbunas will all feed on the algae carpeting the rocks and the tiny creatures within it—and yet a fish will patiently seek a mate of its own species rather than breed with another.

Stauffer was careful, when looking for new species, to not only look for distinctive morphological features but also to observe who exactly was mating with whom. A casual observer might assume that the ubiquitous blue zebras are all the same species, but Stauffer and other taxonomists have described more than 13 different species of blue zebra mbuna in Lake Malawi alone.

“I got tired of people asking me what the blue fish was,” said Kenneth McKaye, who described ten new species of blue zebra in a paper with Stauffer in 1999.

McKaye and I were drinking coffee on the deck of his treehouse, which overlooks a long sandy beach. He is a trustee of a group that runs the EcoLodge at Cape Maclear, but he’s no beach bum: A leading cichlid biologist, McKaye taught at Duke and Yale. In 2009, he gave up his university affiliations to live at Lake Malawi and study the fish on his own.

McKaye was confounded by the sheer number of cichlid species in Lake Malawi. How were the fish branching off into new species at such a fast rate while living together in the same environment? The answer, McKaye explains, is the cichlids’ fondness for beauty contests—run by the females.

For instance, within a mixed population of mbuna, the females—even the ones that are drab, with only a few brown or black markings—seek out males with extremely specific color patterns. Females of Labeotropheus trewavasae seek out blue males with red dorsal fins, rarely mixing with males of Labeotropheus fuelleborni, which look similar except their dorsal fins are also blue.

It’s not uncommon for an animal to have some degree of choosiness when it selects a mate. Darwin called this phenomenon sexual selection, and it’s familiar to anyone who has watched a nature documentary where birds perform elaborate courtship dances. But the reasons behind sexual selection are not always clear. Survival of the fittest should guide species toward practical traits like strength or ability to find food. How could an ornate train help a peacock exploit its niche?

Darwin believed some animals simply had a “taste for the beautiful,” an attraction to purely aesthetic traits that confer no fitness or advantage. The idea that female birds simply enjoy colorful feathers and elaborate dances did not catch on—the Yale ornithologist Richard Prum has said his colleagues treat it like a “crazy aunt in the evolutionary attic.” Still, there’s no question that female peacocks like fans of colorful feathers and female birds of paradise like elaborate courtship dances.

Some scientists believe these traits often signal a degree of overall good health that could support strong offspring and long-term vitality. But over the generations, sexual selection can exaggerate traits to the point where they would seem to actually impede survival—for instance, producing long, cumbersome ornaments or colors so bright that they draw extra attention from predators.

In the case of cichlids, the tastes of the females are so fixed and specific that it’s hard to see how they’d point to an evolutionary advantage for the male. “It can be a totally arbitrary trait,” says Alex Jordan, a cichlid researcher affiliated with the Max Planck Institute. Among sand-dwelling cichlids of Lake Malawi, for instance, some females are drawn to the males that move sand with their mouths to build the biggest bowers—crater-like structures or mounds on the lakebed. Other females favor the males that perform the most elaborate figure-eight dances. The differences keep

getting more pronounced with every generation: The male offspring of the figure-eight swimmers may become even better at swimming figure eights, and the females may become even more attached to that particular trait. This creates a positive feedback loop that can create a new species of cichlid in as few as 20 generations. (Most cichlids reach sexual maturity at around 6 months.)

“In my lifetime, they could spin out another species or two,” McKaye told me. This is much faster than new species evolve through natural selection alone, which would require waiting for an advantageous mutation to randomly arise.

McKaye says the number of cichlid species could keep growing at the same dizzying rate if it weren’t for one phenomenon: the overfishing of Lake Malawi. The human population of Malawi has doubled over the past 20 years, and the demand for food has led to newer fishing practices that are emptying out the waters. Young boys sieve the shoreline with mosquito nets so fine that juvenile fish cannot escape, and bottom trawlers are destroying the depths. Malawians like to fish for catfish and chambo, an especially large cichlid that can grow to be more than a foot long; now they complain that the fish, captured before they are fully grown, are much smaller than they used to be. The demands being placed on Lake Malawi are expected only to increase: The human population is projected to triple between 2010 and 2050. “I’m now at the stage where everything I push is conservation,” McKaye said, “so people can study the system I did.”

* * *

The cichlids are faring better in protected areas of Lake Malawi National Park, which has recently been enforcing fishing laws. “The fish here are in the best shape they’ve been in for two decades,” McKaye said. After a few days of snorkeling, I wanted to observe the fish more closely. The EcoLodge runs a scuba diving school, and I signed up for a course with Maher Bouda, an Algerian man with long, sun-streaked hair. Bouda has plumbed the Great Barrier Reef, the Andaman Sea and the Red Sea, and he came to Lake Malawi because he wanted to experience something different: It was one of the only freshwater environments that could hold a match to the coral reefs he knew so well.

It is also a great place for a new diver. The lake has no currents or tides. The idea of being 60 feet underwater still made me nervous, but my anxiety dissolved as soon as I reached the lake floor. I was weightless in warm water, wrapped in silence and focused on my breath. The cichlids did not mind me—in fact, I realized I was closer to wild exotic animals than I had ever been on land. Toward the end of my first dive I looked to my right and saw dozens of blue zebras swimming beside me, as though I were just another member of their school. “The cichlids like to follow divers,” Bouda told me after we returned to the boat.

We took our second dive in an area called the Canyon, near West Thumbi Island. Its walls were a mosaic of mbuna pecking at the moss, narrowing toward a floor of sandy bowers. We swam to some boulders, where I noticed a blue-and-yellow male from the genus Tropheops wiggling his tail by the mouth of a female fish.

It was an unusual behavior I had looked forward to observing: a male cichlid fertilizing eggs while they were inside a female’s mouth. Most female cichlids in Lake Malawi lay their eggs and then suck them into their cheeks. After the babies are born, the females “mouth brood”—spitting out their babies to forage and chase off predators, then sucking their offspring back in to carry them around the lake.

Bouda and I emerged from an underwater cave onto a field of boulders, where I noticed a female Fossorochromis rostratus, an insect-eating cichlid, on the sand between two rocks. Her tiny fry were almost invisible, and she began inhaling them as we floated overhead.

We were not alone, however. A school of mixed mbuna had followed us again. I figured they posed no threat, since most mbuna were algae-eaters—but they were also opportunists who would snag some protein if given a chance. The mbuna swarmed the unprepared mother and her fry. Overwhelmed, she quit sucking up her babies and began chasing off individual attackers, which only created more opportunities for other cichlids to strike. I watched a blue fish and a yellow one separate a pack of fry from their kin and devour them in the sand. After a few minutes, the frenzy was over and the Fossorochromis mother hovered among her attackers, as though she were just another member of their school.

Our oxygen was running low, so we swam to the surface and climbed aboard the boat. Large waves clapped against the hull, and on West Thumbi Island a white-headed African fish eagle sat vigilant in a tree. My head was still swimming, though. I had seen up close and in detail something that was supposed to only be visible from a great distance: the engine of evolution, churning out a marvelous array of underwater life.

An hour after that last diving session, I was dressed and packed, ready to take several buses back to Lilongwe, and then several flights back home. I knew it was unlikely that I would return soon to Malawi, though I understood why someone like McKaye would stay for a decade. “Every time you do something in Lake Malawi,” he told me, “you discover how much you don’t know.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1f/7d/1f7d6d16-f29e-4ebd-b005-f0cf2092a70c/mar2019_g04_malawi_resized.jpg)