Why the Valley of the Gods Inspires Such Reverence

The haunting beauty of an ancient desertscape

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/07/61/076188af-a06a-43a3-8ccf-da4bdac4febc/bw6nba.jpg)

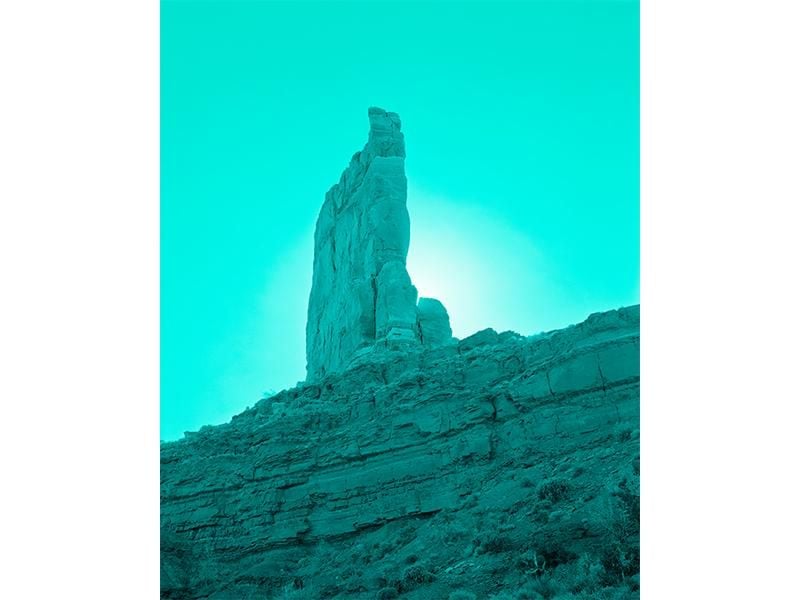

To the west of Bluff, Utah, in the state’s southeast corner, an unassuming 17-mile gravel road branches off from U.S. Route 163. The path cuts an arc through cultural and geological riches aptly named the Valley of the Gods, where red-rock formations tower hundreds of feet in the air, sculpted by the earth’s most reliable architects, wind and water.

Buttes and soaring pinnacles are shaded orange and red from the oxidized iron within, their Cedar Mesa sandstone dating back over 250 million years. Line after horizontal line, the years unfold vertically, the striations of time shimmering in the heat like a Magic Eye puzzle. The arid plain is dotted with blooming yucca in the spring, sage and rabbit brush, Indian paintbrush and other wildflowers. Life endures in the cracks of the world as it always has, in caves and trunk hollows. The San Juan River, lifeblood of the Four Corners area, lies to the south, carving gorges as it surges westward to meet the Colorado River.

It is no wonder the Valley of the Gods is sacred to the Navajo, whose mythology holds that these grand spires contain the spirits of Navajo warriors. Indeed, the greater Bears Ears area around the Valley contains more than 100,000 sites of cultural significance to Native Americans, including the creation mythologies of tribes such as the Ute and Navajo, for whom Bears Ears is akin to their Garden of Eden. The area serves as a history book written in fossils and artifacts, in the bones of indigenous ancestors and the plants that healed and fed them. In 2008, the federal government acknowledged this extraordinary legacy by protecting the Valley of the Gods, designating it an Area of Critical Environmental Concern for its “scenic value.” Then, in December 2016, during his final full month in office, President Obama designated the Bears Ears area, including the Valley of the Gods, as a national monument. Among other things, the move recognized the land’s importance to native tribes, and came after decades during which the health of those tribes suffered profoundly from nearby uranium mines and the resulting groundwater poisoning—not to mention high rates of lung cancer and disease among native miners.

Then, in 2017, President Trump shrank Bears Ears National Monument by 85 percent and Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, another protected area in southern Utah, by almost 47 percent. The change, the largest single reduction in federal land protections in U.S. history, was in response to what the administration characterized as overreach by former presidents. But the Washington Post reported that a uranium-mining firm had actively lobbied the administration to reduce Bears Ears, and the New York Times found that lobbyists had been indicating which parcels of land the companies wanted to be opened to industry.

Shortly after the reduction, companies leased over 50,000 acres from the Bureau of Land Management for oil and gas extraction east of the former borders of Bears Ears National Monument. This February, the Department of the Interior finalized its plan to make much of the former monument available not only to cattle grazing, but to mining interests as well.

For now, the Valley of the Gods itself is off limits to development and mining interests; it still enjoys protections based on the 2008 designation, even though the shrunken Bears Ears National Monument no longer includes it. Another thing in its favor is obscurity. Visitors to the region are far more inclined to visit the larger and more popular Monument Valley, the backdrop of countless Hollywood westerns, which is about 30 miles away on sovereign Navajo land. Thus the Valley retains something truly rare: wildness, in its utmost sense.

The 1964 Wilderness Act defined wilderness as “an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain.” Those who are drawn to the Valley of the Gods’ solitude and spires may explore its roughly 32,000 acres without the likelihood of encountering another person. Camping is permitted but only at established sites. Everything one needs to survive must be packed in and out. As a reward for self-sufficiency, one gets the brilliance of the night sky on a new moon—the serenity of the darkness without the crowds who overrun so many of Utah’s breathtaking wilds.

Edward Abbey, the 20th century’s famed cantankerous chronicler of the Southwest, wrote about the Valley of the Gods in The Monkey Wrench Gang, his adventurous novel about ecological saboteurs fighting against the development and exploitation of the region’s natural resources. “Ahead a group of monoliths loomed against the sky, eroded remnants of naked rock with the profiles of Egyptian deities,” Abbey wrote of the Valley. “Beyond stood the red wall of the plateau, rising fifteen hundred feet above the desert in straight, unscaled, perhaps unscalable cliffs.”

Were Abbey alive today, he would likely be thrilled to find the landscape that he knew: no trails, no services, no fees, no permit, no visitor center—a place, not a park, whose precious, eons-old wildness survives, for the moment, intact.

Landmark Decisions

It's a privilege that comes with the White House, but preserving U.S. property for history's sake is no walk in the park—by Anna Diamond

Since 1906, presidents have used the Antiquities Act to designate 158 national monuments, covering over 700 million acres, to safeguard their natural or social history. That power has sparked disputes about federal overreach, and lands set aside by one president can always be changed by another—or by Congress.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.