Vaunted Vancouver

Set between the Pacific Ocean and a coastal mountain range, the British Columbia city may be the ultimate urban playground

Shafts of sunlight soften the brooding darkness of the Canadian Pacific rain forest, shadowed under a canopy of 200-foot-high Douglas firs. A rustle of pine needles turns out not to signify the slithering of an unseen snake—merely a winter wren darting through the underbrush. Now comes a sonic burst, as a downy woodpecker drills into a nearby trunk. On a branch overhead, blackcap chickadees join in a dee-dee-dee chorus. “What’s that?” I ask my naturalist guide, Terry Taylor, detecting a trilling whistle within a cathedral-like stand of red cedars. “Ah, that,” says Taylor, who is also a practitioner of deadpan Canadian humor. “That is a small bird.”

Taylor’s narrative is punctured, however, by some decidedly non-bucolic sounds—the buzz of seaplanes ferrying passengers to nearby towns and resorts, and the foghorn blasts of multitiered cruise ships pulling away from their Vancouver, British Columbia, berths, heading north to Alaska. Stanley Park, the 1,000-acre rain forest we are exploring, lies at the heart of the city—the preserve covers almost half of its downtown peninsula. As a New Yorker, I have been known to brag about the landscaped elegance of Manhattan’s Central Park and the restorative powers of ProspectPark in Brooklyn. But even I have to admit that those green spaces pale in comparison to this extraordinary urban wilderness.

In what other city in the world can one ski on a nearby glacier in the morning—even in summer—and sail the Pacific in the afternoon? Where else does the discovery of a cougar wandering around a residential neighborhood fail to make the front page of the local newspaper? The big cat, according to an account buried inside the Vancouver Sun, was sedated and released in a more distant wilderness setting. The article included a “cougar hotline,” along with advice on tactics to be employed should readers encounter a snarling beast in their own backyards: “Show your teeth and make loud noises . . . if a cougar attacks, fight back.”

The great outdoors has dictated much of the city’s recent development. “We have guidelines that establish corridors between buildings to protect essential views of the mountains and water,” says Larry Beasley, Vancouver’s codirector of planning. Perhaps as a result, the hundreds of nondescript office buildings and apartment towers erected during the past 20 years appear to have been designed not to compete with stunning vistas of the blue Pacific and the snow-capped Coast Mountains. “Once developers complete a project of ten acres or more, they are required to dedicate substantial acreage to communal space, including parks,” says Beasley. Vancouver has added 70 acres of new parkland to its inner city in the past decade, particularly along the miles of waterfront looping around the city’s many inlets.

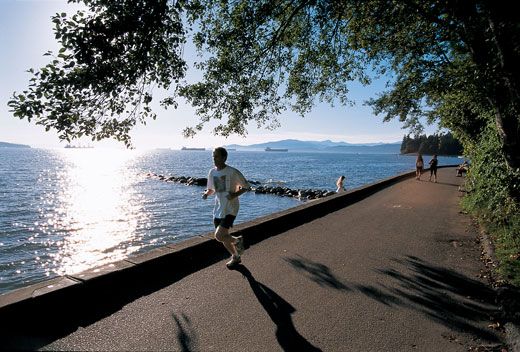

To show off this unique marriage of city and nature, Beasley conducts a walking tour through parts of the downtown peninsula not covered by rain forest. We begin in False Creek, an up-and-coming neighborhood. The waters here, once polluted, are now swimming clean. In-line skaters, bicyclists and joggers stream past a flotilla of sailboats tethered in the marina. Mixed-income residential towers and adjoining parkland rise on land formerly occupied by railroad yards. Afew blocks north, False Creek abuts Yaletown, a SoHo-like neighborhood of lofts, restaurants, galleries and high-tech enterprises fashioned out of a former warehouse district. “What we’re aiming for is a 24-hour inner city, not just a town where everybody heads for the suburbs when it gets dark,” says Beasley.

Statistics bear out his claim that Vancouver “has the fastest-growing residential population of any downtown in North America.” In 1991, the city had a population of 472,000; a decade later, it had risen to 546,000. “And yet,” Beasley boasts, “we have fewer cars than ten years ago.” There’s more to come, due to massive investment and a surge in tourism, both tied to the 2010 Winter Olympics to be held here.

Still, my walk back to my hotel is sobering. At Victory Square Park, located in a section known as Downtown Eastside, a contingent of perhaps 100 homeless people are living in tents, their settlement rising against a backdrop of banners reading “Stop the War on the Poor” and “2010 Olympics: Restore Money for Social Housing.”

I meet over coffee at a nearby bar with Jill Chettiar, 25, an activist who helped raise this tent city. “We wanted to draw attention to the fact that all this money is being spent on a socially frivolous project like the Olympics, while there are people sleeping in doorways,” says Chettiar. She estimates that half the tent dwellers are drug addicts; many suffer severe mental disorders. At night, the homeless are the only people visible in the 30-square-block district of single-roomoccupancy buildings, flophouses and alleys. “We’re living in a society that would rather turn its back on these people for the sake of attracting tourists,” says Chettiar.

But most Vancouverites welcome the Winter Olympics, remembering, as many of them do, Expo 1986—which drew an astounding 21 million visitors to the city and converted it, virtually overnight, into a major destination for tourists and immigrants alike. Of the latter, the most visible newcomers are Asians, particularly Hong Kong Chinese, who began to relocate here in anticipation of Hong Kong’s 1997 reversion to China after a century of British colonial rule. Others are eastern Canadians, lured by the mild climate and lotus land image. “It’s called the Vancouver disease,” says Carole Taylor, chairwoman of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation’s board of directors (and no relation to Terry Taylor). “Companies hesitate to send their employees to Vancouver because they fall in love with the outdoors and the food and the lifestyle, and at some point they decide to stay rather than move up the ladder elsewhere.” Taylor knows. Thirty years ago she came here on assignment as a television reporter to interview the mayor, Art Phillips. Not only did she stay, but she ended up marrying the guy.

Vancouver has been seducing its visitors for a while now. Some theories hold that migrating hunters, perhaps crossing from Siberia into Alaska over the Bering Strait some 10,000 years ago, were enticed into a more sedentary life by the abundant fish and wild fruit found here. Various native tribes who settled here—now called First Nations people—created some of the most impressive cultures in pre-Columbian North America. “The access to food resources enabled people to establish a complex, hierarchical society and develop art to reflect ranking, particularly exemplified by massive structures like totem poles. Those constructions show crests representing family lineage and histories. Also, a person’s rank in the tribe was indicated by the number of poles that individual could afford to raise,” says Karen Duffek, curator of art at the Museum of Anthropology.

The museum, designed by Vancouver-based architect Arthur Erickson and completed in 1976, is located on the campus of the University of British Columbia (UBC); its postand-beam construction echoes the Big House structure of traditional First Nations dwellings. The Great Hall is lined with totem poles—elaborately embellished with carved animal and human figures, some realistic, others fantastic—which in tribal cultures were used as corner posts to hold up ceiling beams. An adjoining space contains a collection of enormous communal banquet dishes; the largest looks something like a 12-foot-long dugout canoe, hewn in the shape of a wolf. The feast dishes, Duffek says, were used for potlatch (derived from a word for “gift”) ceremonies, important social and political occasions in preliterate societies where a chieftain’s largesse might be distributed and a great deal of knowledge transmitted orally. “A potlatch ceremony to install a new chief could last for several weeks,” Duffek adds.

Contemporary works are on display as well. The Raven and the First Men, a six-foot-high 1980 wood sculpture by the late Haida artist Bill Reid, depicts a mythological incident of the bird discovering the first men hidden in a clamshell. Outdoors, perched on a cliff overlooking a Pacific inlet, loom other Reid pieces—totem poles depicting bears, wolves, beavers and killer whales, some beginning to morph into human shapes. Suddenly, a real bald eagle, driven aloft by sea gulls protecting their nests, slices the air no more than 30 feet away from us.

Europeans came late to this corner of westernmost Canada. Spanish explorers arrived in the area first, in 1791. And a year later, a small naval expedition commanded by George Vancouver, who had served as midshipman to Capt. James Cook in the South Pacific, surveyed the peninsula. Yet it was not until 1886, with the coming of the Canadian Pacific Railroad, that an isolated hamlet here, Granville, was officially christened Vancouver. Connecting the country from Atlantic to Pacific, the railroad made possible the exploitation of forests, mines and fisheries—the fragile pillars of Vancouver’s early prosperity. “There was a boom-and-bust instability linked to natural resource extraction; a lot of wealth was wiped out at the turn of the 20th century because of speculation,” says Robert A.J. McDonald, a historian at UBC. “So you didn’t have the more permanent banking and manufacturing fortunes of New York, Boston and Toronto.”

Nonetheless, remnants of the original Anglo-Saxon elite still prevail in the hilltop neighborhoods rising above Vancouver harbor—Shaughnessy’s mock-Tudor mansions, the many horse stables of Southlands and the English village-style shops of Kerrisdale. I join Stephanie Nicolls, a third-generation Vancouverite who owns a marketing and media relations firm, for high tea at the Secret Garden Tea Company, in Kerrisdale, where shop-window posters invite residents to celebrate Coronation Day—Queen Elizabeth’s half-century on the throne. Awhite-aproned waitress sets down a feast of finger sandwiches, scones, clotted cream and pastries. “The descendants of the old elite are still around, but they don’t run Vancouver anymore,” says Nicolls. “Anybody can play in the sandbox now.”

She cites the venerable Vancouver Club, a handsome, five-story, members-only establishment with a front-row view of harbor and mountains. Built in 1913, the red-brick edifice, its interior replete with marble floors, crystal chandeliers and early 20th-century Canadian portraits and landscapes, was long an all-male Northern European bastion. “Then, about ten years ago, the board asked us younger members what we wanted done at the club—and actually let us do it,” says Douglas Lambert, the 39-year-old president.

Today, 20 percent of the members are women; East and South Asian faces are visible around the dining room and bar. The average age of a new member is now 35. “No more three martini lunches,” says Lambert. Gone, too, are florid-faced gentlemen given to snoozing in armchairs or wafting cigar smoke across the billiard room. Instead, a state-of-the-art gym offers yoga classes along with the usual amenities. What has not changed is the club’s status as a watering hole for the business elite—three-quarters of the city’s CEOs are members. “But the definition of ‘the right kind of people’ has evolved and broadened,” says Lambert.

Milton Wong, 65, financier and chancellor of Simon Fraser University in suburban Vancouver, grew up in the city at a time when the “right kind of people” most emphatically did not include Asians. Born in 1939, he is old enough to remember the internment of Japanese Canadians in the country’s interior during World War II. (Chinese Canadians did not get the vote until 1947; Japanese Canadians followed in 1949.) “My two older brothers graduated as engineers from UBC but were told, ‘Sorry, no Chinese are being hired,’ ” recalls Wong. “They had to go back into the family tailoring business.”

By the time Wong graduated from UBC in 1963, the bias had eased; he became a stock portfolio manager. He ended up making a fortune for many of his investors. “Maybe I didn’t think wealth was the most important thing in life, but everybody else seemed to view it as a sign of success,” says Wong. “They started to say, ‘Gee, if people trust Wong with all that money, he must be smart.’ ”

Funds have undoubtedly diluted prejudice against the 60,400 Hong Kong Chinese who have moved here in the past decade, abetted by Vancouver’s direct flights to Hong Kong. Canada readily granted permanent residence to immigrants who demonstrated a net worth of (U.S.) $350,000 and invested (U.S.) $245,000 in a government-run job-creation fund. “Perhaps it was a lot easier to accept immigrants who drive Mercedes,” quips Jamie Maw, a real estate banker and magazine food editor. Even today, some heads of households continue to work in Hong Kong and visit their families in Vancouver for long weekends a couple of times a month. In fact, Richmond, a southern suburb that is home to the city’s airport, has become a favored residential area for Hong Kong Chinese immigrants. Nearly 40 percent of Richmond’s residents are Chinese, twice the percentage of Chinese in the metropolitan area.

“It’s easy to spend a whole day at the mall,” says Daisy Kong, 17, a high-school senior who lives in Richmond. Kong, who moved here only eight years ago, would like to return to Hong Kong someday. But for her friend Betsy Chan, 18, who plans to study kinesiology at SimonFraserUniversity, Hong Kong would be an option only if she were offered a better job there. “I have a mixed group of friends, and even with my Chinese friends, we usually speak only English,” says Chan, who prefers rafting, hiking and rock climbing to browsing the stores in the mall. Ricky Sham, 18, who is soon to enroll at the University of Victoria, says Chan has obviously gone native. “You won’t see Chinese-speaking Chinese hanging outdoors,” he says. “My friends go to pool halls and video arcades.”

Another group of recent arrivals—American filmmakers—also prefer the city’s indoor attractions. “People all over the world rave about the great outdoors and stunning film locations in British Columbia. We offer the great indoors,” claims a Web site advertisement for one of the half-dozen local studios. The message has been heeded in Hollywood. On any given day here, anywhere from 15 to 30 movies and television shows are in production, making Vancouver, a.k.a. “Hollywood North,” the third-largest filmmaking center in North America after Los Angeles and New York. The television series “X-Files” was filmed here, as were such recent features as Scary Movie 3, X2, Snow Falling on Cedars and Jumanji.

“The beautiful setting put us on the map originally,” says Susan Croome, the British Columbia film commissioner. “Filmmakers could travel a couple of hours north of L.A., in the same time zone, speak the same language, get scenery here they couldn’t get there—and at less cost. From that followed the development of talented film crews and well-equipped studios where sets can be built quickly.”

At Mammoth Studios, a former Sears, Roebuck warehouse in suburban Burnaby, an L.A. production team is filming Chronicles of Riddick, an intergalactic adventure starring Vin Diesel. (As sci-fi cognoscenti are well aware, this is a sequel to Pitch Black, in which Diesel also plays a likable outer space sociopath who vanquishes even nastier goons.)

Still dressed in suit and tie from previous interviews, I arrive late by taxi at the wrong end of the aptly named Mammoth Studios. I’m told the production office, where I’m expected, is located the equivalent of three city blocks away in a straight line through several sets—or about double that distance if I were to skirt the sets. I opt for the indoor route, and have barely begun before I’m thoroughly embarrassed by a booming megaphone voice: “Yoooh . . . the man in the business suit, you are walking through a live set!”

This production employs a crew of about 1,000 Vancouverites, including some 600 skilled laborers and artists for stage construction and 45 seamstresses to outfit the wardrobes of villains, victims and heroes. “There’s no point in coming to Vancouver unless you take full advantage of the local resources,” says Scott Kroopf, the film’s producer, who has produced some 30 films with his former partner, Ted Field. “We looked at Australia and the United States, but we couldn’t find indoor space like this.”

Kroopf’s 14-hour days at Mammoth Studios leave him time only for Vancouver’s other great indoor activity—eating. The natural ingredients for a remarkable cuisine have long existed here: line-caught sockeye salmon and trap-caught Dungeness crab; mushrooms gathered in the rain forest; a cornucopia of vegetables and herbs harvested in FraserValley to the east of the city. But it was the fusion of traditional European recipes with Asian cooking, brought over by more recent Chinese, Japanese, Indian, Thai and Vietnamese immigrants, that created a dazzling spectrum of world-class restaurants. And visitors from Hollywood have helped spread the gastronomic reputation of the city far and wide.

I join Marnie Coldham, sous-chef of Lumière, arguably the city’s top restaurant, on an early morning shopping expedition. We begin at the Granville Island Public Market, located under a bridge connecting downtown Vancouver to more residential neighborhoods to the south; Granville’s stands lie inside a warehouse-size enclosure. Coldham heads first for the butchers, where she picks up sausages and doublesmoked bacon, beef short ribs, ham hocks and veal bones. At the fishmonger’s, she chooses lobster, wild salmon and a dozen varieties of oyster. The fruit stalls are stocked with raspberries the size of gum balls, blueberries as large as marbles, and produce once available only in Asia—green papaya, for instance, or litchi nuts.

Crossing back over the bridge into downtown Vancouver, we stop at the New Chong Lung Seafood and Meat Shop in Chinatown. “We use their barbecued duck for our Peking duck soup,” says Coldham, pointing to several birds hanging on hooks by the window. An elderly Chinese woman employs a net to scoop giant prawns out of a tank. I survey the ice-lined crates containing sea snails, rock cod, sea urchin and a Vancouver favorite, geoduck (pronounced gooey-duck)—a giant clam. “Oooooh—look at this!” exclaims Coldham, as we pass a neighboring shop with a stack of durians, Southeast Asian fruit that look something like spiky rugby balls and are characterized by a distinctive, stomach-turning stench—and a compensating smooth texture and sweet taste.

That night, much of this produce (no durians) is served me for dinner. “Vancouverite palates have become very demanding,” says Rob Feenie, Lumière’s chef and owner. Lumière’s décor is minimalist-contemporary; I would be hard pressed to remember the furnishings beyond vague impressions of pale wood and beige fabrics. I have no trouble, however, conjuring up the medley of dishes devoured, with the help of a friend, during three hours of feasting: lightly seared tuna with celeriac rémoulade; maple-syrup- and sake-marinated sablefish with sautéed potatoes and leeks; braised duck leg and breast and pan-seared foie gras with cinnamonpoached pear; squash and mascarpone ravioli with black truffle butter; raw milk cheeses from Quebec; and an assortment of white and red wines from the vineyards of the Okanagan Valley, a four-hour drive northeast of Vancouver. “Because we’re on the Pacific Rim, there’s a huge Asian influence in my dishes—lots of fresh, even raw, fish,” says Feenie. The subtle sweetness, though, evokes the fresh, fruity tastes I often associate with the traditional elements of Pacific Northwest cuisine.

Vancouver’s exquisite scenery and world-class dining have lent the city a laid-back image—a representation some insist is exaggerated. “It’s no more accurate than the notion that East Coast Americans have of L.A. as a less businesslike place to be,” says Timothy Taylor, a local writer (and yet another unrelated Taylor). The narrative in his acclaimed first novel, Stanley Park, shuttles between the downtown rain forest preserve and the kitchen of a gourmet restaurant. “In fact,” he goes on, “people here work as hard as in Toronto or New York.”

But for now, at least, Vancouver does suffer by comparison to those cities in terms of its more limited cultural offerings. It occurs to me that not once during my stay did anyone suggest I attend a concert, opera or dance performance. In the bookstores I wandered into, locating anything beyond bestsellers and self-improvement tomes posed a challenge. But then, this is a young city—barely 120 years old. It took awhile for the First Nations people to create their wondrous totem poles and Big Houses—only after their food needs were met by a surfeit of fish and game. I contemplate the cultural masterpieces that surely lie ahead, created by a people raised on a diet of pink scallops in Peking duck soup, pan-seared halibut with morels, and green pea and ricotta ravioli.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.