Venezuela Steers a New Course

As oil profits fund a socialist revolution, President Hugo Chávez picks a fight with his country’s biggest customer the United States

Lunch was on the patio, overlooking a green valley an hour's drive west of Caracas. The hostess, wearing a small fortune in St. John knits, snapped at one of the uniformed waiters for failing to top off my glass of guava juice. Over dessert, the conversation turned to the squatters who with the encouragement of President Hugo Chávez's leftist government were taking over private lands. Campaigning had begun for next December’s presidential election, and the guests worried that pro-Chávez rallies would, as in years past, end in tear gas and gunfire. “There will certainly be more violence,” murmured one of them, a sleekly coiffed television broadcaster.

Later, as the family chauffeur ran to get the car to take me back to my hotel, the hostess’s brother-in-law winked at me. “He claims we work him too hard,” he said. “We call him el bobolongo”—the moron.

The driver’s name is Nelson Delgado. He is an agronomist by training. He used to teach, but he took the chauffeur job because he could not find one that paid more. On the way back to Caracas, he confided that his prospects were improving. He had joined one of the land “invasions” that so concern his present employers; he and a few hundred fellow squatters were planning to build homes and start farming on their plot. He had also applied for a government job—one of many now available under Chávez’s “Bolívarian revolution”—evaluating farmers who applied for loans. He figured he wouldn’t be a chauffeur much longer.

When I asked how my hostess and her family might fare in the revolutionary future, Delgado paused a moment before answering: “As long as they cooperate, they’ll be OK.”

venezuela’s meek are beginning to inherit the earth—or at least a share of the oil wealth underground—and it is making them much bolder. No political leader before Chávez has so powerfully embodied their dreams—or given them so much money. Like 80 percent of his 25 million countrymen, the president, a former army paratrooper, comes from the lower classes. Elected in 1998, reelected under a new constitution in 2000 and widely expected to win another six-year term next December, he has spent more than $20 billion over the past three years on social programs to provide food, education and medical care to the neediest.

In the United States, Pat Robertson might like to see Chávez assassinated—as the Christian broadcaster suggested in August—but Chávez’s countrymen are, on the whole, supportive of the president. National polls last May showed that more than 70 percent of Venezuelans approved of his leadership. “Comedians used to make fun of our government officials,” says Felix Caraballo, 28, a shantytown dweller and father of two who studies at a new government-subsidized university. “They’d say, ‘We’re going to build a school, a road, clinics.’ . . . And then they’d say, ‘We’ve thought about it, but we’re not going to do it.’ Today, thanks to Chávismo”—as Chávez’s political program is known—“another world is possible.”

Chávez, 51, is one of the most contradictory caudillos ever to tackle Latin America’s intractable poverty and inequity. He’s a freely elected coup plotter (jailed for rebellion in 1992), a leftist with a fat wallet and a fire-breathing foe of the U.S. government, even though his treasury relies on gas-guzzling gringos. Oil provides roughly half of Venezuela’s government income, and the United States—“the Empire,” to Chávez—buys some 60 percent of its oil exports.

In his first year in office, Chávez won a popular vote for a new constitution, which, among other things, changed his nation’s name to the Bolívarian Republic of Venezuela to honor his hero, Simón Bolívar (1783-1830), the independence leader from Caracas, the capital. Since then, Chávez’s friendship with Cuba’s Fidel Castro and his attempts, à la Bolívar, to unite his neighbors against “imperialists” have provoked hostility from Washington. (Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice has called him a “negative force” in the region.) At home, Chávez has weathered a 2002 coup (he was reinstated after two days of domestic and international protests), a 63-day national strike in 2002-03 and a recall referendum in 2004, which he won with 58 percent support.

Through it all, Venezuelans of all classes have become obsessed with politics, to the point where families have split along political lines. As wealthy conservatives have fled to Miami or hunkered down, expecting the worst, unprecedented hope has come to people like Delgado and Caraballo, who were among a few dozen Venezuelans I met on a recent visit. I arrived with three questions: Is Chávez simply throwing Venezuela’s oil wealth at the poor, as his critics say, or are his plans more far-reaching and sustainable? How democratic is his revolution? And how long can the United States coexist with Chávez-style democracy?

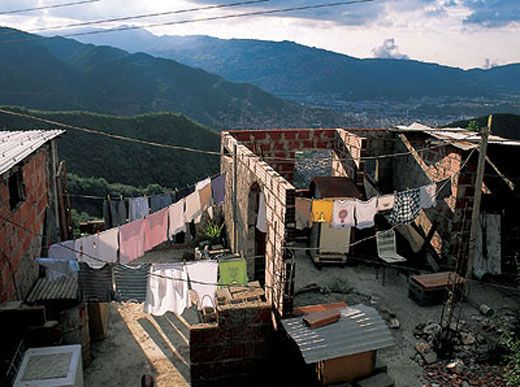

Chávez’s supporters say that to appreciate his vision, you must first look to the hillside shantytowns that ring Caracas. One of them—La Vega, on the city’s western edge—is where Felix Caraballo lives. It takes roughly an hour to get there from downtown—by private taxi and then one of the communal jeeps that dares the steep, rutted ascent, paralleling a sewage ditch lined with avocado and banana trees.

The journey helps explain why many frequent travelers to Latin America prefer almost any other national capital to Caracas. The streets are choked with traffic, the air with black exhaust. On one side of the road stand skyscrapers; on the other flow the remains of the Guaire River, a concrete canal filled with runoff and sewage. Only the view of Mount Avila, its bright green peak rising more than 7,000 feet above the sprawl, relieves the dreariness.

On the journey there, Caraballo told me that while he was growing up in the 1980s, his family—all engineers on his father’s side—had fallen from middle class to poor, like hundreds of thousands of other Venezuelan families in that era of slumping oil prices. When we reached the hilltop and outer limit of La Vega, he showed me a neighborhood that was trying to reverse the descent.

Caraballo said that Sector B, as it is known, was safer than in previous years, the police having killed a small gang of crack dealers several weeks before. There were also tangible signs of progress. Residents could shop at a brand-new market, its shelves stacked with sugar, soap, powdered milk and bags of flour, all marked down as much as 50 percent. The red brick medical clinic was also new, as were the ten Dell computers in the air-conditioned wireless Internet center, staffed by two helpful technicians. In one home, half a dozen students, ages 12 to 40, sat at wooden school desks, taking free remedial high-school classes. Some of them received government stipends of $80 a month to attend.

The market’s food came in plastic bags printed with progovernment slogans, the clinic’s doctors were Cuban imports and the remedial lesson I observed was an explanation of rainfall that would be third-grade material in a U.S. classroom—yet they were all splendid gifts in a country where roughly half the population earns less than $2 a day.

Of course, daily life in La Vega bears little semblance to the self-image Venezuela’s elite held dear for most of the past century. Oil wealth has given rise to grand aspirations ever since 1922, when a blowout sprayed “black rain” over the small town of Cabimas. By 1928, Venezuela had become the world’s largest oil exporter, with Venezuelans of all classes acquiring costly Yanqui tastes. The country has long been one of the world’s top five per capita consumers of whiskey and is a major Latin American market for Viagra.

In 1976, the government nationalized its subsoil wealth. High oil prices and stable politics allowed for grand living: a trip to Disney World was a rite of passage even for the children of some parking lot attendants, and Venezuelan shoppers in Miami were known as the Dáme dos (“Give me two!”) crowd. But by 1980, oil prices began to fall, and the hard times that followed revealed the ruling class as graft-hungry and, worse, managerially inept. In 1989, President Carlos Andrés Pérez (later impeached for corruption) clumsily imposed an austerity program, which, among other things, increased bus fares. Riots broke out; Pérez called out the army, and more than 200 people were killed in the infamous suppression dubbed “el Caracazo”—Caracas’ “violent blow.”

Chávez, then a midcareer lieutenant who had studied Marxism and idolized Che Guevara, was among the troops called to put down the protests. He was already plotting rebellion by then, but he has cited his outrage at the order to shoot his compatriots as a reason he went ahead, three years later, with the coup attempt that made him a national hero.

Hugo Chávez was one of six children of cash-strapped primary school teachers in western Venezuela, but he dreamed big. “He first wanted to be a big-league [baseball] pitcher, and then to be president,” says Alberto Barrera Tyszka, coauthor of the recent Venezuelan bestseller Hugo Chávez Sin Uniforme (Chávez Without His Uniform). “At 19, he attended Pérez’s presidential inaugural, then wrote in his diary: ‘Watching him pass, I imagined myself walking there with the weight of the country on my own shoulders.’ ”

After his coup attempt, Chávez was so popular that almost every candidate in the 1993 presidential campaign promised to free him from jail; the winner, Rafael Caldera, pardoned him in one of his first official acts. Eventually Chávez joined with leftist politicians and former military colleagues to launch the Fifth Republic Movement, and in December 1998, having never held a political post, he was elected Venezuela’s president with 56 percent of the vote.

He moved quickly: within a year, his new constitution replaced a bicameral Congress with a single-chamber National Assembly and extended the presidential term from four years to six, with the right to immediate reelection. Thus Chávez’s first term officially began with the special election of 2000. Since then, he has used his outsider appeal to transform both the presidency and the government.

He likes to speak directly to his constituents, especially on his Sunday TV show, “Aló, Presidente.” Appearing often in a bright red shirt and jeans, he talks for hours at a time, breaks into song, hugs women, gives lectures on nutrition and visits sites where people are learning to read or are shopping for subsidized groceries. He quotes Jesus and Bolívar, inveighs against capitalism and excoriates the “oligarchs” and the “squalid ones”—the rich and the political opposition. And he rarely misses a chance to taunt the U.S. government. While Chávez has made the most out of Robertson’s call for his assassination—he declared it “an act of terrorism”— he has long suggested that Washington is out to get him. He has notoriously called President Bush a pendejo, using a vulgar term for “jerk,” and he has threatened to cut the United States off from Venezuelan oil. At the United Nations in September, he told a radio interviewer that there was “no doubt whatsoever” the United States “planned and participated in” the 2002 coup and wanted him dead. (The Bush administration waited six days after the coup collapsed before condemning

it but insists it played no part in the coup.)

“He wants to present himself as the great enemy of Bush, and he does it very well,” biographer Barrera told me. “All of us Latin Americans have a few grains of anti-imperialism in our hearts, because the U.S. foreign policy here has been such a disaster”—a reference to U.S. cold war plots against elected leaders and support for right-wing dictators in Guatemala, Chile, Cuba, Nicaragua and elsewhere. “So each time he says he’s anti-imperialist and the U.S. reacts, it excites people all over Latin America—and Europe. The U.S. falls into his trap as if 40 years with Castro taught you nothing.”

Yet the Bush administration has understandable reasons for thinking of Chávez as a threat. One is that Bush’s plans for new, hemisphere-wide trade pacts depend on Latin Americans’ goodwill. But Bush is extremely unpopular in the region, while Chávez has whipped up support with in-your-face opposition to the United States combined with neighborly generosity. He has offered other Latin American nations financial aid and oil while encouraging them to oppose U.S.-led trade overtures. At the Summit of the Americas in early November, he sought to bury a measure Bush has favored, telling a cheering crowd of some 40,000: “Each one of us brought a shovel, a gravedigger’s shovel, because [this] is the tomb of the Free Trade Area of the Americas.” (Before Thanksgiving, he sought to slight Bush by offering discounted heating oil to the poor in a few U.S. cities through his state-run oil company’s U.S. subsidiary, Citgo.)

In addition, high-ranking Bush administration officials suggest that Chávez is funneling support to radical movements elsewhere in Latin America, particularly in Colombia and Bolivia. They point to Chávez’s recent purchase of 100,000 Russian AK-47s. Venezuelan officials say they are for use by civilian militias to defend against a U.S. invasion. Oil is another U.S. concern—though perhaps not to the degree Chávez likes to suggest. In 2004, Venezuela was the fourth-ranking oil exporter to the United States, sending approximately 1.3 million barrels a day, or about 8 percent of the total U.S. supply. Chávez has promised to increase shipments to oil-thirsty China, but building a pipeline through Panama for trans-Pacific shipments could take several years and considerable expense. Amore immediate concern, with ramifications for U.S. oil customers, is that Venezuela’s staterun energy company is, by many accounts, going to seed because money that normally would have been reinvested in it has gone instead to Chávez’s social programs.

For now, the U.S.“Empire” is the only geographically feasible market for Chávez’s exports. But oil remains his trump card as he keeps up his enthusiastic spending in the months before this year’s election. And while the new constitution limits him to just one more presidential term, he says he has no plans to retire before 2023.

U.S. officials appear to be making similar calculations. When I asked one how long he thought the revolution might last, he answered glumly, “As long as Chávez lives.”

Among Venezuelans, however, the more pressing question is where Chávez plans to lead them now. chávez’s image as a symbol of success for the downtrodden strikes a chord with the majority of Venezuelans who were dismissed by the rich for so many decades, Barrera says. “He eliminates the shame of being poor, of being darkskinned and not speaking the language very well.” But improved self-esteem would mean little without more tangible results. In recent surveys by the Caracas market research firm Datos, a majority of Venezuelans said they had benefited from government spending on food, education and healthcare. In 2004, the average household income increased by more than 30 percent.

Oil, of course, makes it all possible. The gross domestic product grew by more than 17 percent in 2004, one of the world’s highest rates. The government’s budget for 2005 increased 36 percent, and Chávez also is free to dip into Venezuela’s foreign currency reserves for even more social spending. Officials say they are now moving beyond the showy gifts of La Vega to more transformative achievements, such as creating thousands of workers’ cooperatives, subsidizing small and medium businesses with loans and steering growth outside the cities. Even the military officers who once posed the most serious threat to Chávez’s rule seem to have calmed down after yearly promotions and hefty pay raises. Chávez’s determination to put Venezuela’s poor majority in the limelight has won him support from some unlikely sources. “I’m the only one in my family who sympathizes with him,” Sandra Pestana, the daughter of wealthy industrialists, told me on the evening flight from Houston. “They say, ‘You don’t know what it’s like to live here; this guy is crazy.’ ” AU.S.-trained psychologist, Pestana has lived in the San Francisco Bay Area since 1988, but she visits Caracas every year. She grew up accustomed to servants and said it never dawned on her that she had lived “a fairy tale life” until the day she found herself, in tears, cleaning the bathroom in her new home. That epiphany led her to new empathy for the millions of Venezuelans who toil for the upper classes.

Now, Pestana looks back on her youth as “horribly embarrassing,” and yearns to tell her rich relatives “not to flash their money around so much anymore, to be a little bit more sensitive.” Pestana said she sees Chávez as making the country “more like the United States. He’s burst the bubble of colonialism, that’s what he’s done. I don’t like the polarization he has caused, but the rich here were unmovable. . . . From my Americanized eyes, he is democratizing Venezuela.”

Many Venezuelans would take issue with her last point, noting new laws sharply limiting freedom of expression. As of this year, anyone who with “words or in writing or in any other way disrespects the President of the Republic or whomever is fulfilling his duties” can be sent to prison for up to 30 months. Exposing others to “contempt or public hatred” or publishing inaccurate reports causing “public panic or anxiety” invites longer terms.

The laws are a “Damocles sword—we’re permanently threatened,” said Teodoro Petkoff. Aformer leftist guerrilla, he escaped from a high-security prison in the 1960s by faking a gastric ulcer; in the mid-1990s, he served as President Caldera’s minister of economic planning. Now a vigorous 73-year-old, he needles the government with his afternoon newspaper, TalCual (How It Is).

While no journalist has yet gone to jail, half a dozen have been accused of libel or other crimes under the new rules, Petkoff said, and others seem to be censoring themselves. He, too, has felt the heat—“Just yesterday, the attorney general called me a CIA tool,” he said, “which is ridiculous, since I am more against Bush than Chávez is”—yet he appears to have escaped serious persecution because of what he calls his “evenhandedness”: he criticized both the 2002 coup and the general strike, although he clearly is no fan of Chávez’s.

“I knew Chávez before he was president, and I never liked his authoritarianism, his undemocratic style,” Petkoff told me. But most offensive to him is what he says is a squandering of Venezuela’s oil wealth. “Obviously, one of the ways you have to spend it is in social programs to alleviate the poverty of the immense majority of the population,” he said. “But of course you have to spend it in an organized, audited way.”

As the presidential campaign takes shape, few Venezuelans expect opposition to Chávez to unite behind a strong candidate. Petkoff allowed that he was considering running himself, but suggested that would happen only if Chávez’s appeal begins to fade. “I’m not a kamikaze,” he said.

Lina Ron, a stocky, bleached-blonde firebrand, leads one of the so-called Bolívarian Circles, or militant citizens groups, sure to be supporting Chávez in the coming election. I met her at the leafy Plaza Bolívar, during a ceremony honoring the 438th anniversary of the founding of Caracas. Wearing a camouflage jacket, cap and khaki scarf, and surrounded by similarly outfitted women, she ascended a stage and threw her arms around a grinning minister of defense, Orlando Maniglia. Dozens of people then encircled her and followed as she moved through the plaza, trying to catch her attention, get her autograph, or beseech her for favors.

Ron made her way through streets crowded with kiosks selling T-shirts, buttons and keychains adorned with the faces of Che Guevara and Chávez, toward what she calls “the Bunker,” a warren of offices in a small plaza redolent of urine and garbage. “For the people, everything! For us, nothing!” she shouted to her admirers before slipping away.

Ron is a radio broadcaster and founder of the Venezuelan People’s Unity Party, which she says is made up of “radicals, hard-liners and men and women of violence.” In the chaos after the 2002 coup attempt, she led a mob that attacked an opposition march; dozens of people were hurt by gunfire, rocks and tear gas. Chávez has hailed her as “a female soldier who deserves the respect of all Venezuelans” but also once called her “uncontrollable.” While she holds no government title, ministries “channel resources through her,” said a woman who was taking calls for her at the Bunker.

Of late, Ron has focused her attention, and ire, on María Corina Machado, an industrial engineer who is vice president of the election monitoring group Sumate (Join Up), which supported the recall petition against Chávez in 2004. Machado and three other Sumate officials have been ordered to stand trial for treason for accepting $31,000 from the U.S. Congress-controlled National Endowment for Democracy to run voter education workshops before the referendum.

Machado, 37, says she is not seeking office, but the government evidently sees her potential appeal as a kind of Latin Lech Walesa in high-heeled sandals. Chávez has called her and the other defendants “traitors.” Ron has called her a “coup-plotter, fascist and terrorist.” When she met President Bush at the White House in May, it hardly eased the tension.

“The environment is totally scary,” Machado told me in flawless English. Sumate’s offices were crowded with computers and volunteers, and on Machado’s desk two cellphones and a Blackberry rang intermittently. She had posted a printed quotation ascribed to Winston Churchill: “Never give up! Never give up! Never, ever, give up!”

A trial was scheduled for early December, Machado said, and a judge, not a jury, would decide the case. Asingle mother of three facing a maximum sentence of 16 years in prison, she said she was trying not to think about the possibility of having to go to jail. “Our only hope is to continue to be visible,” she said. “If we lower our heads, if we stop working, if we stop denouncing, we’ll be hit harder. Our best defense to postpone or delay action against us is to work harder.”

Before becoming a political activist, Machado worked in the auto-parts firm where her father was an executive and helped run a foundation for street children. Driven by concern that Chávez was eroding democracy, she helped found Sumate in 2001. “We were half a dozen friends, all engineers, with no experience in politics. If we’d had experience,” she said, laughing, “we probably wouldn’t have done it.”

Their initial plan was to collect signatures to take advantage of a mechanism in Chávez’s new constitution allowing for the recall of public officials. But Sumate has also monitored polling places and has been auditing computerized voter registration lists.

Machado believes that Chávez is the consequence rather than the cause of Venezuela’s troubles. “It’s true that the rich ignored the poor,” she said. “Now people are saying, ‘I finally exist. President Chávez represents my dreams, my hopes.’ He’s an amazingly effective spokesperson. But we’re not in a race for popularity. We’re trying to show democracy is a system that gives you a better standard of living.”

Like so many others I interviewed, Machado seemed hopeful about what she described as a new self-confidence among Venezuelans. She argued that all the political turmoil had made people appreciate the importance of participating in politics themselves, of not relying on political parties to defend their rights. Yet the scene outside the Miraflores Palace a few hours after my visit to Sumate suggested that true empowerment will take some time.

Under a blazing midday sun a scraggly line of petitioners stretched up the block from the palace’s wrought-iron gates. Some said they’d been waiting as long as 15 days, sleeping in relatives’ homes or on the street. All were seeking Chávez’s personal attention. Flood victims wanted new homes; an unemployed police officer wanted her job back; an elderly woman wanted medicine. Bureaucracies had failed them, but as Sulay Suromi, a copper-haired woman with a black parasol who’d taken a bus three hours from her home in Carabobo state, told me, “Chávez is a man who sees people.”

“I’m 100 percent Chávista,” boasted Suromi, who was hoping to get title to a parcel of free land so she could build a tourist posada.

Just then a tall, balding man walked up from the end of the line and angrily declared: “This government doesn’t work! They’re not going to help you!”

Suromi and half a dozen other women shouted him down. “Of course they won’t help you—you’re useless!” yelled one.

“Go back home!” shouted another.

From behind the fence, two uniformed guards approached and gently told the crowd to keep waiting. The tall

man ambled back to the end of the line. Another man saw me taking notes and politely asked if I were from the CIA.

Venezuela’s revolutionary future may be played out in scenes like this, as the expectations Chávez has raised start to bottleneck at the figurative palace gates. Unemployment, by government measures, is above 12 percent, and some analysts believe it is actually several points higher. Underemployment, represented by the hundreds of kiosks multiplying in downtown Caracas, has also swelled. Inflation, expected to reach 15 percent in 2005, has been another concern, with economists warning that at the least, Chávez is pursuing good intentions with bad management.

Edmond Saade, president of the Datos polling firm, said his surveys show a marked decline in confidence in the government since April. Yet Saade noted that that feeling had not translated into a rejection of Chávez. “He’s not at all to blame by the general public; he’s adored,” Saade said. Asked how long that might last, he shrugged. “If you manage populism with good controls and efficiency, you can last a long time.

But so far, this is not what Chávez is doing. And if oil prices drop again, the whole revolution becomes a mirage.”

Still, every Venezuelan I talked to said the country has changed in some irreversible ways. The poor have had their first real taste of the country’s wealth, the rich their first experience of sharing it.

“I am very grateful to Chávez,” said Nelson Delgado, the agronomist chauffeur, as he drove me from my country lunch through the treeless exurban slums toward downtown Caracas. But then he predicted, with the confidence of the formerly meek, that with or without Chávez, Venezuela’s revolution would go forward. “It has to,” he said. “Because there are more of us than there are of them.”

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.