The Centuries-Old History of Venice’s Jewish Ghetto

A look back on the 500-year history and intellectual life of one of the world’s oldest Jewish quarters

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e0/46/e0461188-1e8b-408b-a88f-400a5f2ff2aa/sqj_1510_venice_ghetto_01.jpg)

In March 2016 the Jewish Ghetto in Venice will celebrate its 500th anniversary with exhibitions, lectures, and the first ever production of Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice in the Ghetto’s main square. Shaul Bassi, a Venetian Jewish scholar and writer, is one of the driving forces behind VeniceGhetto500, a joint project between the Jewish community and the city of Venice. Speaking from the island of Crete, he explains how the world’s first “skyscrapers” were built in the Ghetto; how a young Jewish poetess presided over one of the first literary salons; and why he dreams of a multicultural future that would restore the Ghetto to the heart of Venetian life again.

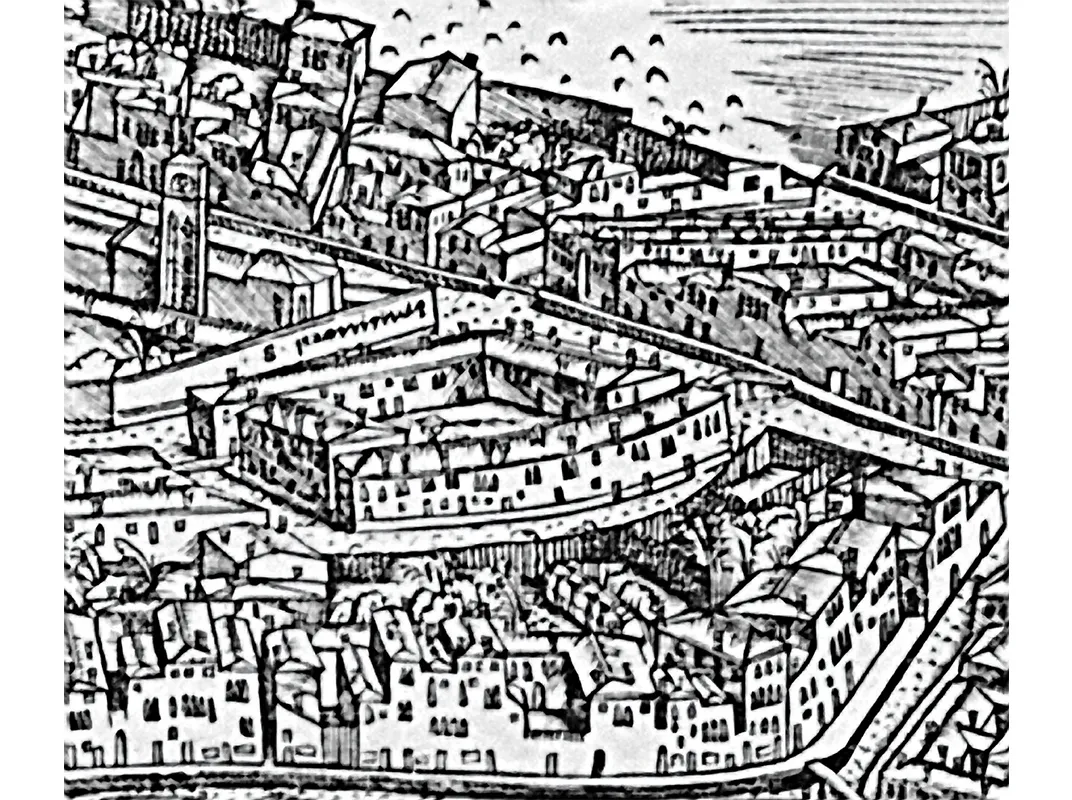

Venice’s Jewish Ghetto was one of the first in the world. Tell us about its history and how the geography of the city shaped its architecture.

The first Jewish ghetto was in Frankfurt, Germany. But the Venetian Ghetto was so unique in its urban shape that it became the model for all subsequent Jewish quarters. The word “ghetto” actually originated in Venice, from the copper foundry that existed here before the arrival of the Jews, which was known as the ghèto.

The Jews had been working in the city for centuries, but it was the first time that they were allowed to have their own quarter. By that time’s standards it was a strong concession and was negotiated by the Jews themselves. After a heated debate, on March 29, the Senate proclaimed this area as the site of the Ghetto. The decision had nothing to do with modern notions of tolerance. Up until then, individual [Jewish] merchants were allowed to operate in the city, but they could not have their permanent residence there. But by ghettoizing them, Venice simultaneously included and excluded the Jews. In order to distinguish them from the Christians, they had to wear certain insignia, typically a yellow hat or a yellow badge, the exception being Jewish doctors, who were in high demand and were allowed to wear black hats. At night the gates to the Ghetto were closed, so it would become a kind of prison. But the Jews felt stable enough that, 12 years into the existence of the place, they started establishing their synagogues and congregations. The area was so small, though, that when the community started growing, the only space was upward. You could call it the world’s first vertical city.

The Jews who settled in the Ghetto came from all over Europe: Germany, Italy, Spain, Portugal. So it became a very cosmopolitan community. That mixture, and the interaction with other communities and intellectuals in Venice, made the Ghetto a cultural hub. Nearly one-third of all Hebrew books printed in Europe before 1650 were made in Venice.

Tell us about the poetess Sara Copio Sullam and the role the Ghetto in Venice played in European literature.

Sara Copio Sullam was the daughter of a wealthy Sephardic merchant. At a very young age, she became a published poet. She also started a literary salon, where she hosted Christians and Jews. This amazing woman was then silenced in the most terrible way: She was accused of denying the immortality of the soul, which was a heretical view for both Jews and Christians. The one published book we have by her is a manifesto where she denies these accusations. She had a very sad life. She was robbed by her servants and marginalized socially. She was hundreds of years ahead of her time. So one of the things we are doing next year is celebrating her achievements by inviting poets to respond to her life and works.

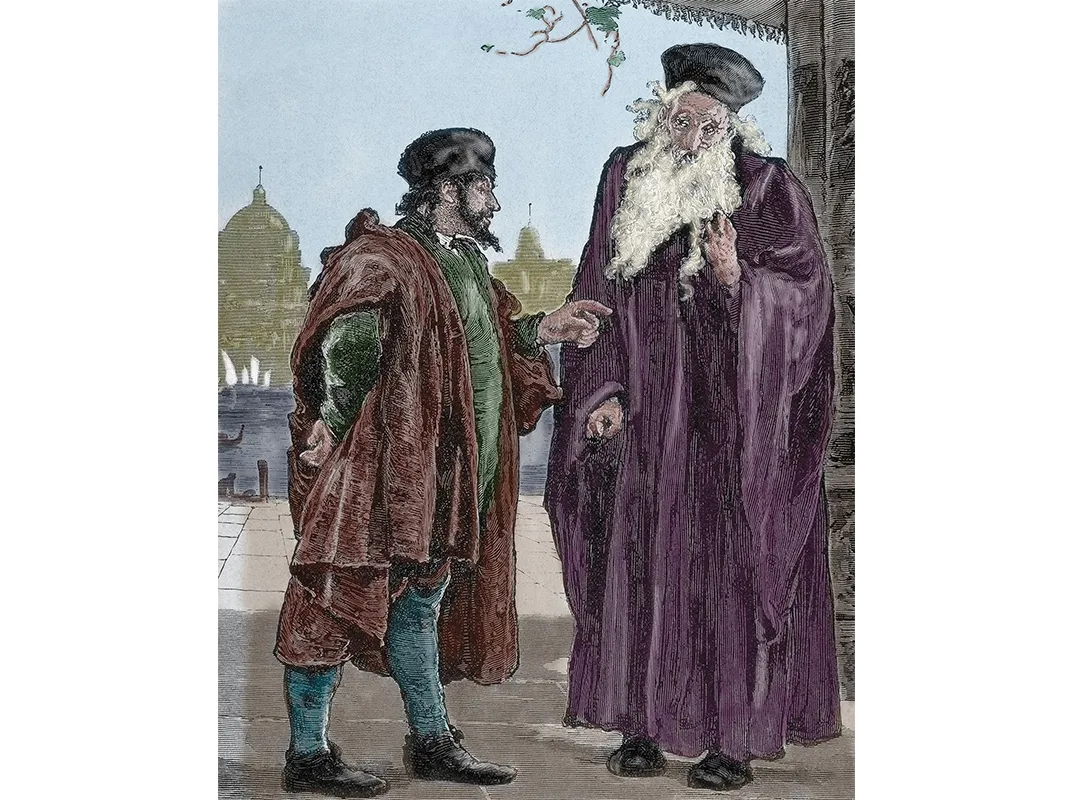

We can’t talk about Venice and Jewish history without mentioning the name Shylock. What are the plans for staging The Merchant of Venice in the Ghetto next year?

We’re trying to bring Shylock back by organizing the first ever performance of The Merchant of Venice in the Ghetto next year. Shylock is the most notorious Venetian Jew. But he never existed. He is a kind of ghost that haunts the place. So we’re trying to explore the myth of Shylock and the reality of the Ghetto. I don’t think that Shakespeare ever visited Venice or the Ghetto before the publication of the play in the First Quarto, in 1600. But news of the place must have reached him. The relationship between Shylock and the other characters is clearly based on a very intimate understanding of the new social configurations created by the Ghetto.

As a city of merchants and dealmakers, was Venice less hostile, less anti-Semitic to Jewish moneylending than other European cities?

The fact that Venice accepted the Jews, even if it was by ghettoizing them, made it, by definition, more open and less anti-Semitic than many other countries. England, for example, would not allow Jews on its territory at the time. Venice had a very pragmatic approach that allowed it to prosper by accepting, within certain limits, merchants from all over the world, even including Turks from the Ottoman Empire, which was Venice’s enemy. This eventually created mutual understanding and tolerance. In that sense, Venice was a multiethnic city ahead of London and many others.

One of the most interesting descriptions of the Ghetto was by the 19th-century American traveler William Dean Howells. What light does it shed on the changing face of the Ghetto and non-Jewish perceptions?

The first English travelers to Venice in the 17th century made a point of visiting the Ghetto. But when the grand tour becomes popular, in the late 18th century, the Ghetto completely disappears from view. Famous writers, like Henry James or John Ruskin, don’t even mention it. The one exception is Howells, who writes about the Ghetto in his book Venetian Life. He comes here when the Ghetto has already been dismantled. Napoleon has burned the gates; the Jews have been set free. The more affluent Jews cannot wait to get away from the Ghetto and buy the abandoned palazzi that the Venetian aristocracy can no longer afford. The people who remain are poor, working-class Jews. So the place Howells sees is anything but interesting.

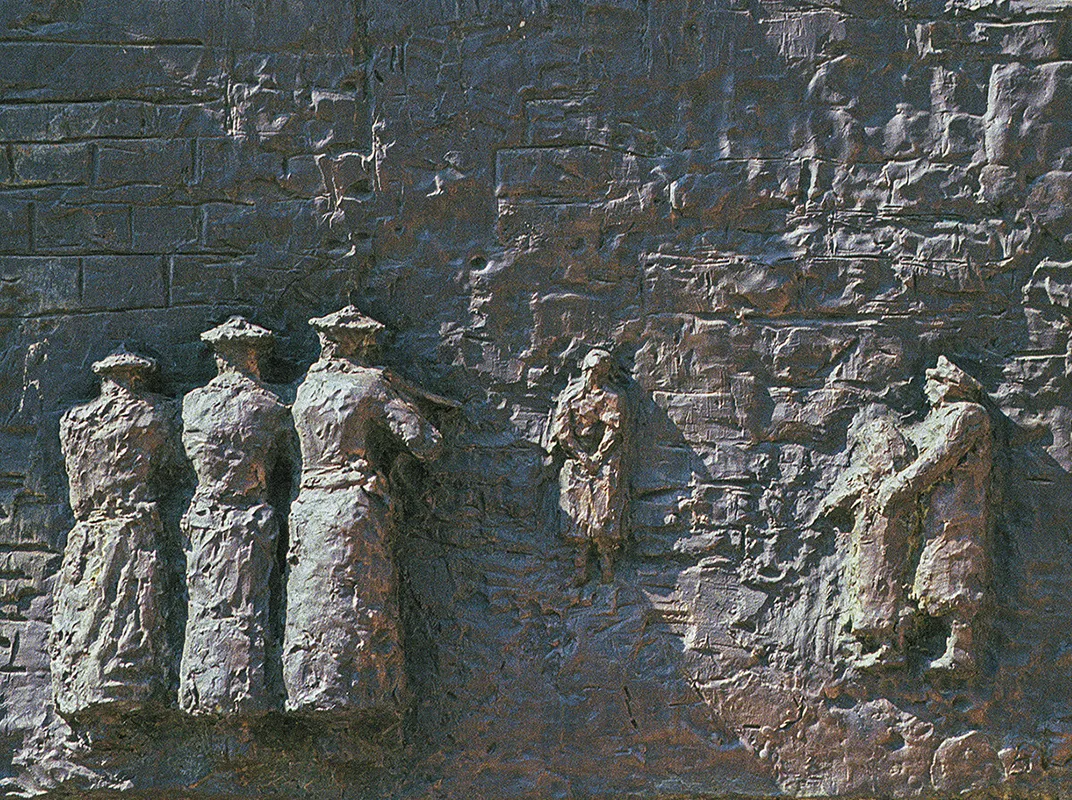

How did the Holocaust affect the Ghetto—and the identity of Italy’s Jewish population?

When people visit the Ghetto today, they see two Holocaust memorials. Some people even think the Ghetto was created during the Second World War! The Holocaust did have a huge impact on the Jewish population. Unlike in other places, the Jews in Italy felt totally integrated into the fabric of Italian society. In 1938, when the Fascist Party, which some of them had even joined, declared them a different race, they were devastated. In 1943, the Fascists and Nazis started rounding up and deporting the Jews. But the people they found were either the very elderly, the sick, or very poor Jews who had no means of escaping. Almost 250 people were deported to Auschwitz. Eight of them returned.

Today the Ghetto is a popular tourist site. But, as you say, “its success is in inverse proportion to the … decline of the Jewish community.” Explain this paradox.

Venice has never had so many tourists and so few residents. In the past 30 years, the monopoly of mass tourism as the prime economic force in the city has pushed out half the population. In that sense the Jews are no different from others. Today the Ghetto is one of the most popular tourist destinations, with nearly a hundred thousand admissions to the synagogue and Jewish Museum per year. But it is the community that makes the Ghetto a living space, not a dead space. Less than 500 people actually live here, including the ultra-Orthodox Lubavitchers. They market themselves as the real Jews of Venice. But they only arrived 25 years ago. Mostly from Brooklyn! [Laughs]

You are at the center of the 500th-anniversary celebrations of the Ghetto, which will take place next year. Give us a sneak preview.

There will be events throughout the year, starting with the opening ceremony on the 29th of March 2016, at the famous Teatro La Fenice Opera House. From April to November, there will be concerts and lectures, and from June a major historical exhibition at the Doges’ Palace: “Venice, the Jews and Europe: 1516-2016.” Then, on the 26th of July, we will have the premiere of The Merchant of Venice, an English-language production with an international cast—a truly interesting experiment with the play being performed not in the theater but in the Ghetto’s main square itself.

You write that “instead of a mass tourism basking in melancholic fantasies of dead Jews, I dream of a new cultural traffic.” What is your vision for the future of Venice’s Ghetto?

“Ghetto” is a word with very negative connotations. There is a risk that Jewish visitors will see it primarily as an example of one of the many places in Europe where Jewish civilization was almost annihilated. I may sound harsh, but it could be said that people like the Jews when they are dead, but not when they are alive. The antidote, in my humble opinion, is to not only observe the past but to celebrate our culture in the present. This could be religious culture but also Jewish art and literature. Why could the Ghetto not become the site of an international center for Jewish culture? We also need more interaction between visitors and locals, so that people who come to the Ghetto experience a more authentic type of tourism. I think that is the secret to rethinking this highly symbolic space. The anniversary is not a point of arrival. It’s a point of departure.

Read more from the Venice Issue of the Smithsonian Journeys Travel Quarterly.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.