Vermont’s Venerable Byway

The state’s Route 100 offers an unparalleled access to old New England, from wandering moose to Robert Frost’s hideaway cabin

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/DA-Vermont-Scott-Bridge-West-River-Vermont-631.jpg)

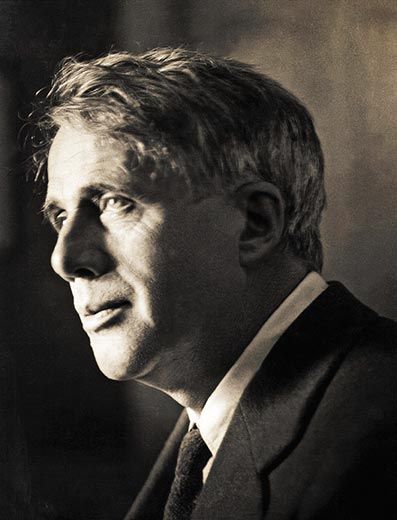

The Robert Frost Cabin lies ten miles west of Route 100, near the midway point in the road’s 216-mile ramble through valleys, woods and farmlands between Massachusetts and Canada. Although I had driven to Vermont many times to ski, I had always taken the interstate, hellbent on reaching the slopes as quickly as possible. This time, however, I followed “The Road Not Taken,” to quote the title of one of Frost’s best-known poems, pausing at the Vermont cabin where he wrote many of them.

I crossed over covered bridges spanning sun-dappled rivers, past cornfields and grazing cows, into a landscape punctuated by churches with tall steeples and 18th-century brick houses behind white picket fences. A farmer rode a tractor across freshly mowed acreage; old-timers stared at me from a sagging porch at the edge of a dilapidated village. My trip included stops at a flourishing summer theater; an artisanal cheese maker in a state famous for its cheddars and chèvres; the 19th-century homestead of an American president; primeval hemlock stands and high passes strewn with massive, mossy boulders; and bogs where moose gather in the early evening. On either side of me rose Vermont’s Green Mountains, the misty peaks that set its citizens apart from “flatlanders,” as Vermonters call anyone—tourist or resident—who hails from across state lines.

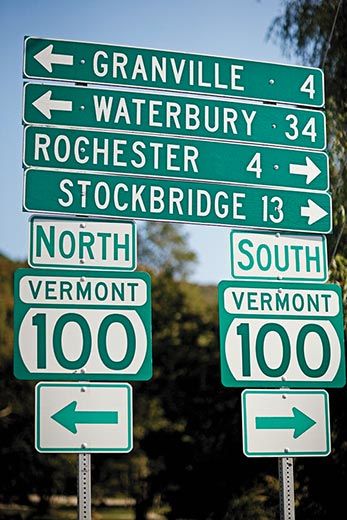

Route 100 grew organically from roads connecting villages dating back to the 1700s, following the contours of the Vermont landscape. “It eventually became one continuous route, curving along rivers and through mountain valleys,” says Dorothy A. Lovering, producer and director of a documentary about the storied country road. “That’s why it offers such remarkable visual experiences.”

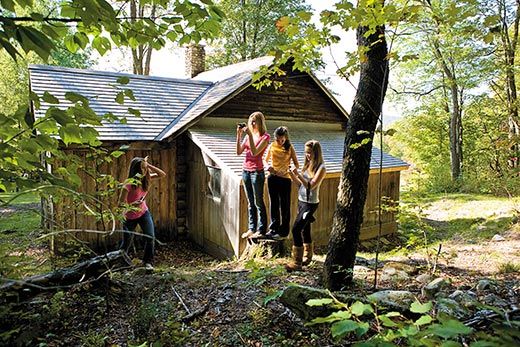

The Frost log-and-wood slat cabin stands in a clearing outside the town of Ripton (pop. 566), where the poet spent summers and wrote from 1939 until his death in 1963 at age 88. (Today, the farm, now a National Historic Landmark, belongs to Middlebury College, which maintains the property as a Frost memorial. The public has access to the grounds.) Behind a forest of 100-foot-tall Norwegian pines, the weathered cabin looks out on an apple orchard, a meadow carpeted in wildflowers and a farmhouse. The vista evokes an image from his poem “Out, Out—”:

Five mountain ranges one behind the other

Under the sunset far into Vermont.

A visit to the site is bittersweet. On the night of December 28, 2007, vandals shattered windows, smashed antiques and damaged books inside the property’s main farmhouse. The intruders caused more than $10,000 in damage. Fortunately, some of Frost’s most cherished belongings—including his Morris chair and a lapboard the poet used as a writing surface—had already been moved to the Middlebury campus. Although marred in the rampage, Frost’s pedal organ has been repaired and remains in the farmhouse. The cabin itself, where Frost etched a record of daily temperatures on the inside of the door, was not disturbed.

Twenty-eight young men and women—ages 16 to 22—were charged with trespassing or destruction of property, then turned over to poet Jay Parini, a Frost biographer and professor of literature at Middlebury, who taught the miscreants about Frost and his work. “I thought they responded well—sometimes, you could hear a pin drop in the room,” recalls Parini. “But you never know what’s going on in a kid’s head.”

I had begun my Route 100 odyssey by driving through that hallowed Vermont landmark—a covered bridge. Turning off Route 100 outside the town of Jamaica (pop. 946), I drove southeast for four miles to reach Scott Bridge—built in 1870 and named for Henry Scott, the farmer whose property anchored one end—in Townshend (pop. 1,149). Spanning the boulder-strewn West River, at 277 feet it is the longest of the state’s 100 or so covered bridges—down from 500 a century ago.

“What’s most fascinating about covered bridges is that they take you back to the origins of our country,” says Joseph Nelson, author of Spanning Time: Vermont’s Covered Bridges. Durability was their primary virtue: uncovered bridges were lashed by rain and snow. The wet wood attracted insects and fungus, then rotted away and had to be replaced every four or five years. Today, Vermont boasts covered bridges built in the early 1800s. In the 19th century, the interiors “doubled as local bulletin boards,” writes Ed Barna in his Covered Bridges of Vermont. “Travelers stopping to wait out rainstorms or rest their teams could inspect the bills and placards advertising circuses, religious gatherings, city employment in the woolen mills, and nostrums like Kendall’s Spavin Cure and Dr. Flint’s Powder, two widely known remedies for equine ills.”

Local officials specified that a covered bridge should be erected “a load of hay high and wide.” A rusted plate over one entrance to Scott Bridge posts a speed limit: “Horses at a walk.” But equines gave way to heavier motorized traffic, which weakened the structure. Since 1955, the bridge has been closed to all but pedestrian traffic.

About 25 miles north of Scott Bridge, just off Route 100, Vermont’s oldest professional theater faces Weston’s charming village green. (In 1985, the entire town, with its concentration of 18th- and 19th-century architecture, was placed on the National Register of Historic Places.) The Weston Playhouse opened in 1937 with a youthful Lloyd Bridges starring in Noel Coward’s Hay Fever. The original theater, housed in a converted Congregational church, burned down in 1962, when an overheated gluepot caught fire. The church was quickly reconstructed, right down to its white-columned Greek Revival facade.

“Our audiences like the fact they are seeing some of Broadway’s latest shows as soon as they are available,” says Steve Stettler, who this summer is directing a production of Death of a Salesman. Stettler came to the playhouse in 1973 as an actor fresh out of Kenyon College in Ohio. For the current season, the playhouse will also offer The 39 Steps, a play based on the Alfred Hitchcock murder mystery, productions of the hit musicals Avenue Q and Damn Yankees, and the world première of The Oath, a drama focusing on a doctor caught in the horrors of the Chechen conflict.

Sixteen miles north, the hamlet of Healdville is home to the 128-year-old Crowley Cheese Factory, today owned by Galen Jones, who in his day job is a New York City television executive. He and his wife, Jill, own a house in Vermont and plan to retire here eventually. “If you look at it dispassionately, it’s not a business that looks like it’s ever going to make a significant amount of money,” says Jones of the cheese-making operation. “But it’s a great product.”

As far back as the early 1800s, Vermont’s dairy farms were turning milk into cheese, mainly cheddars of a kind first introduced from Britain during colonial times. But with the invention of refrigerated railroad cars in the late 19th century, Midwestern dairy facilities claimed most of the business. Crowley, one of the few Vermont cheese makers to survive, carved out a niche by producing Colby, a cheddar that is smoother and creamier than most.

Cheese-making staged a comeback in Vermont in the 1980s, as demand increased for artisanal foods produced by hand. The number of cheese makers in the state more than doubled—to at least 40—in the past decade. And the University of Vermont, in Burlington, has established an Artisan Cheese Institute. At Crowley’s stone-and-wood frame, three-story factory, visitors can view the stages of production through a huge plate-glass window. On weekday mornings, 5,000 pounds of Holstein raw milk, chilled to 40 degrees, is pumped from refrigerated storage in the cellar to a double-walled, steam-heated metal vat, where it is cultured. About four hours later, the milk has been processed into solidified chunks, or curd. It is then rinsed, salted and shaped into wheels or blocks, ranging in weight from 2 1/2 to 40 pounds, before being pressed, dried, turned and moved into storage for aging.

The cheddar produced here comes in nine varieties, according to mildness or sharpness and the addition of pepper, sage, garlic, chives, olives or smoke flavor. While the largest Vermont cheese makers churn out 80,000 pounds daily, Crowley’s takes a year to produce that much.

Ten miles or so northeast of Healdville lies Plymouth Notch, the Vermont village of white houses and weathered barns where President Calvin Coolidge spent his childhood. Preserved since 1948 as a state historic site, it remains one of Route 100’s most notable destinations, attracting 25,000 visitors annually.

The village, with its handful of inhabitants, has changed little since our 30th president was born here on July 4, 1872. His parents’ cottage, attached to the post office and a general store owned by his father, John, is still shaded by towering maples, just as Coolidge described it in a 1929 memoir.

“It was all a fine atmosphere in which to raise a boy,” Coolidge wrote. The autumn was spent laying in a supply of wood for the harsh winter. As April softened into spring, the maple-sugar labors began with the tapping of trees. “After that the fences had to be repaired where they had been broken down by the snow, the cattle turned out to pasture, and the spring planting done,” recalled Coolidge. “I early learned to drive oxen and used to plow with them alone when I was twelve years old.”

It was John Coolidge who woke his son—then the nation’s vice president on vacation at home—late on the night of August 2, 1923, to tell him that President Warren G. Harding had suffered a fatal heart attack. John, a notary public, swore in his son as the new president. “In republics where the succession comes by election I do not know of any other case in history where a father has administered to his son the qualifying oath of office,” the younger Coolidge would write later.

Some 40 miles north of Plymouth Notch, Route 100 plunges down into its darkest, coldest stretch—the heavily wooded Granville Gulf Reservation. “Gulf” in this case refers to a geological process from more than 10,000 years ago, when mountaintop glaciers melted. The release of vast quantities of water gouged notches—or gulfs—into the mountains, creating a narrow chasm walled in by cliffs and forest. In 1927, Redfield Proctor Jr., who was governor from 1923 to 1925, donated most of the 1,171 acres of this six-mile ribbon of woodlands to the state, with prohibitions against hunting, fishing and commercial tree-cutting; the tract was to be “preserved forever.”

The section of Route 100 that crosses Granville Gulf was not paved until 1965. Even today, few venture farther than a turnout overlooking Moss Glen Falls, spilling 30 feet over a 25-foot-wide rock face. “It’s gorgeous—a real photo-op,” says Lisa Thornton, a forester at the reserve. She’s right.

Using a map originally drawn by a biologist more than 40 years ago, Thornton leads me toward a wedge of forest on the cliffs. We clamber up a hillside over spongy soil until we reach a stone ledge covered in moss and fern—and a stately stand of 80-foot-tall hemlocks, perhaps 500 years old. The trees survived, Thornton says, because they were virtually inaccessible to Native Americans, European pioneers and timber companies. I’m reminded of Frost’s poem “Into My Own”:

One of my wishes is that those dark trees,

So old and firm they scarcely show the breeze,

Were not, as ‘twere, the merest mask of gloom,

But stretched away unto the edge of doom.

For most of its length, Route 100 is paralleled by a 273-mile footpath that runs along the main ridge of the Green Mountains. Built between 1910 and 1930, the Long Trail preceded—and inspired—the Appalachian Trail, with which it merges for about 100 miles in southern Vermont. Created and maintained by the nonprofit Green Mountain Club, the trail offers 70 primitive shelters amid pine- and maple-forested peaks, picturesque ponds and alpine bogs. “Our volunteers maintain the shelters and keep clear 500-foot-wide corridors on either side of the trail—making sure there are no illegal incursions by timber companies,” says Ben Rose, executive director of the organization.

One of the most accessible—and geologically distinctive—points on the Long Trail is Smuggler’s Notch, a nine-mile drive northwest from Stowe, the town best known for its ski resort, on Route 108, through the Green Mountains. Legend holds that its name dates back to the War of 1812. Trade with Canada, then still an English colony, had been suspended by the U.S. government; contraband goods were allegedly transported through this remote pass.

Huge boulders, some more than 20 feet tall, dot the landscape. “My grandfather used to bring me up here and we would climb past the boulders down to a beaver pond to go fishing,” says my guide, Smith Edwards, 69, nicknamed “Old Ridge Runner” by his fellow Green Mountain Club members. (Edwards has trekked the entire length of the Long Trail four times.) He began hiking the trail as a Boy Scout in the 1950s. “Back then, they would drop off 13-year-old kids and pick us up three or four days later, up the trail 50 miles,” says Edwards, who is retired from the Vermont highway department. “Of course, that wouldn’t be done today.”

We walk a good two hours on the Long Trail, ascending half-way up Smuggler’s Notch, past birches, beeches and maples. Ferns, of which the state boasts more than 80 species, carpet the forest floor. “Here in the moist and shaded gorge they found a setting to their liking,” wrote naturalist Edwin Way Teale in Journey Into Summer (1960), one volume in his classic accounts of travels across America.

Some of the most numerous road signs along Route 100 warn of an ever-present danger: moose. The creatures wander onto the road in low-lying stretches, where tons of salt, spread during winter, wash down and concentrate in roadside bogs and culverts. “Moose are sodium-deficient coming out of their winter browse,” says Cedric Alexander, a Vermont state wildlife biologist. “They have learned to feed in the spring and early summer at these roadside salt licks, which become very hazardous sections to drive through.”

The danger has increased as the state’s moose population has risen, from a mere 200 in 1980 to more than 4,000 today. Their prime predator is the four-wheeled variety. When an animal is struck by a car, the impact often sends the creature—an 800-pound cow or a 1,000-pound bull—through the windshield. At least one driver is killed and many more are injured every year.

The most frequent moose sightings in the state occur along a 15-mile segment of Route 105, a 35-mile continuation of Route 100, especially in early evening, May through July. On this particular night, game warden Mark Schichtle stops his vehicle on Route 105 and points to what he calls “moose skid marks”—black patches made by cars trying to avoid the animals. “Since January, there have been six moose killed just on this stretch,” he says. We park a mile up the road, slather ourselves with mosquito repellent and begin a stakeout.

Within 15 minutes, a moose cow and her calf emerge from the woods and stand immobile on the road, 50 yards away from our vehicle, their dark hides rendering them virtually invisible in the darkness. But a moose-crossing sign alerts drivers, who brake to a halt. Soon, cars and trucks on both sides of the road are stopped; the two moose stare impassively at the headlights. Then, a bull moose—seven feet tall with a stunning rack of antlers—appears, wading in a roadside bog. “No matter how often it happens, you just don’t expect to see an animal that large in the wild and so close by,” says Schichtle.

With cars backing up, the warden turns on his siren and flashing lights. The moose scamper into the bog, and traffic resumes its flow, most of it headed toward New Hampshire. I’m reminded that Robert Frost himself, long a New Hampshire resident, was among the few outsiders wholly embraced by Vermonters. Perhaps that’s because his Pulitzer Prize-winning poem, “New Hampshire,” closes with an ironic twist:

At present I am living in Vermont.

The next day, as I head south on Route 100, bound for the heat and congestion of Manhattan, Frost’s admission is one I would gladly make for myself.

Writer Jonathan Kandell lives in New York City. Photographer Jessica Scranton is based in Boston.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.