Visit Frida Kahlo’s Recreated Garden to See the Plants That Influenced Her Art

The New York Botanical Garden is showing rare paintings and drawings alongside the types of flora Kahlo herself once cultivated

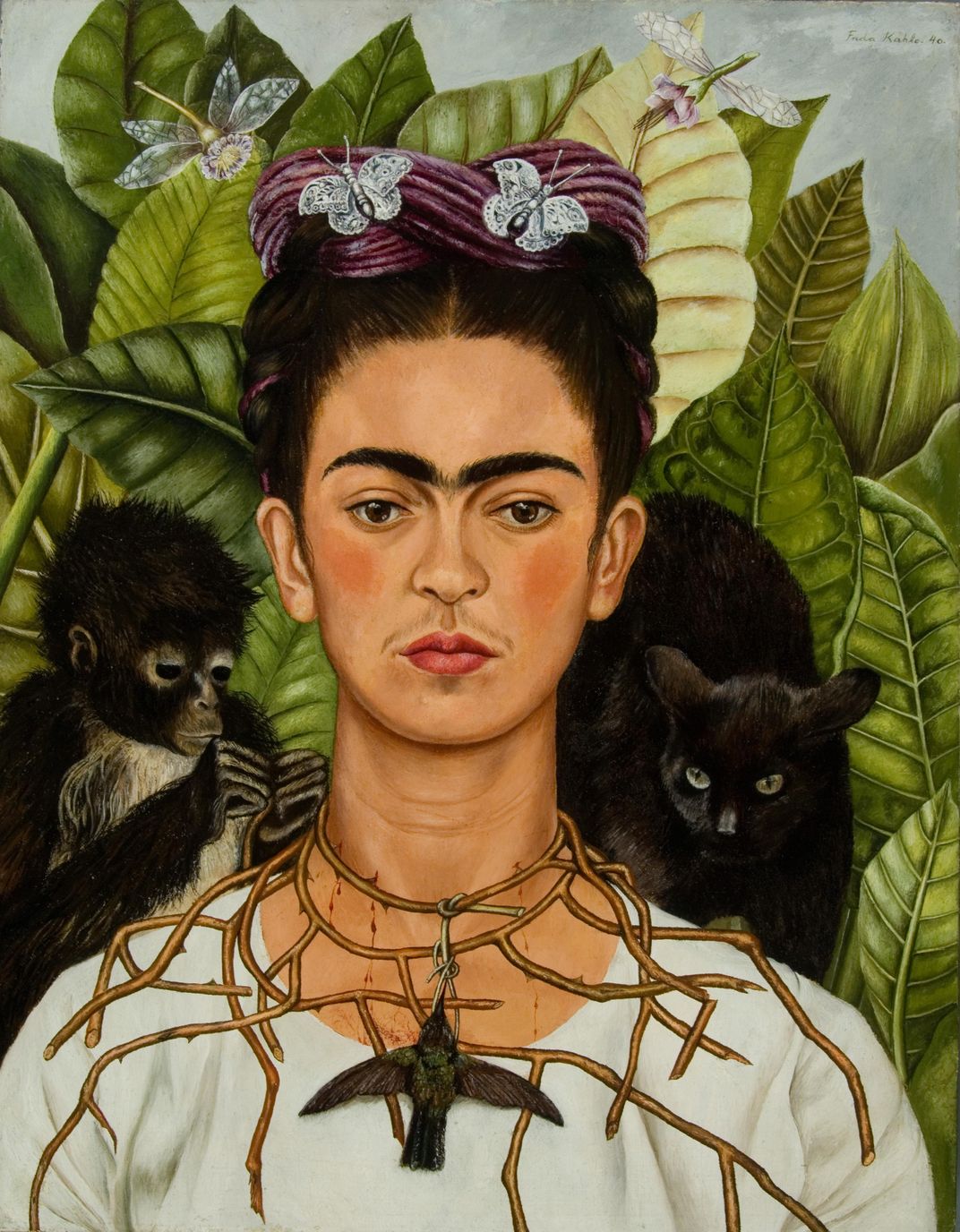

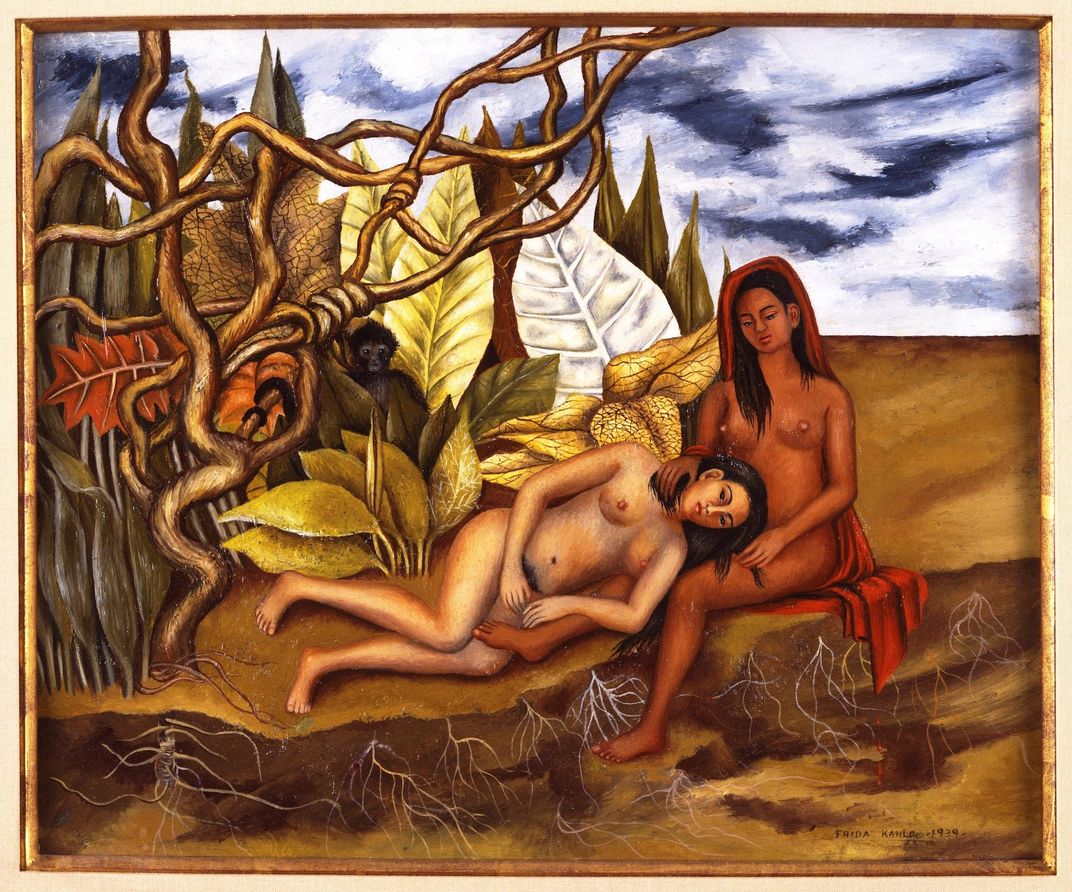

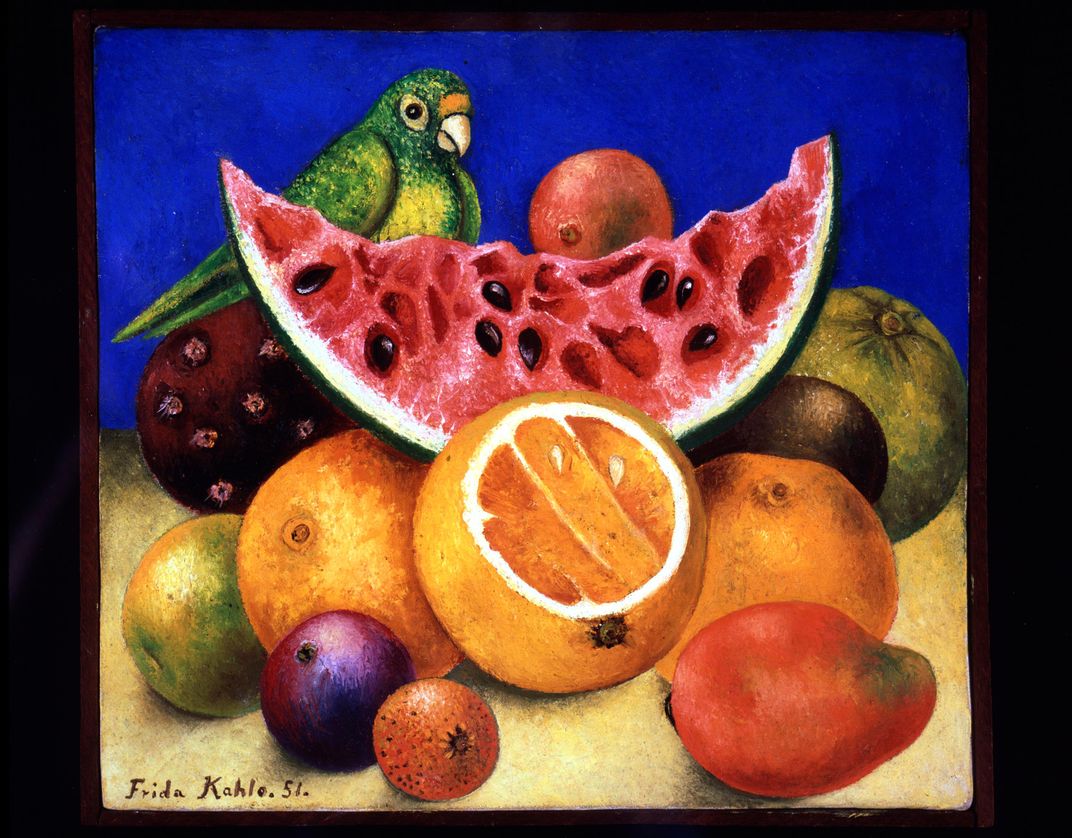

Famed artist Frida Kahlo was also an exquisite gardener, with a deep understanding of plant science. At her home in Mexico City, known as La Casa Azul for its bright blue color and now the site of the Frida Kahlo Museum, Kahlo cultivated plants whose images made their way into her work. A sprawling exhibition at the New York Botanical Garden, Frida Kahlo: Art, Garden, Life, is “the first to examine Frida Kahlo’s keen appreciation for the beauty and variety of the natural world,” and explores the complexity of plant imagery in her artwork.

Guest curator Adriana Zavala, a professor at Tufts University who specializes in Latin American art, points out that whereas many people have looked at Kahlo’s paintings in relation to her tumultuous biography, this exhibition considers her life and work from a less-expected angle. The focus here is Kahlo's interest in plant science, and the way her flora-based paintings reveal her awareness, as Zavala puts it, of Mexico’s long history as a cultural, culinary and botanical crossroads.

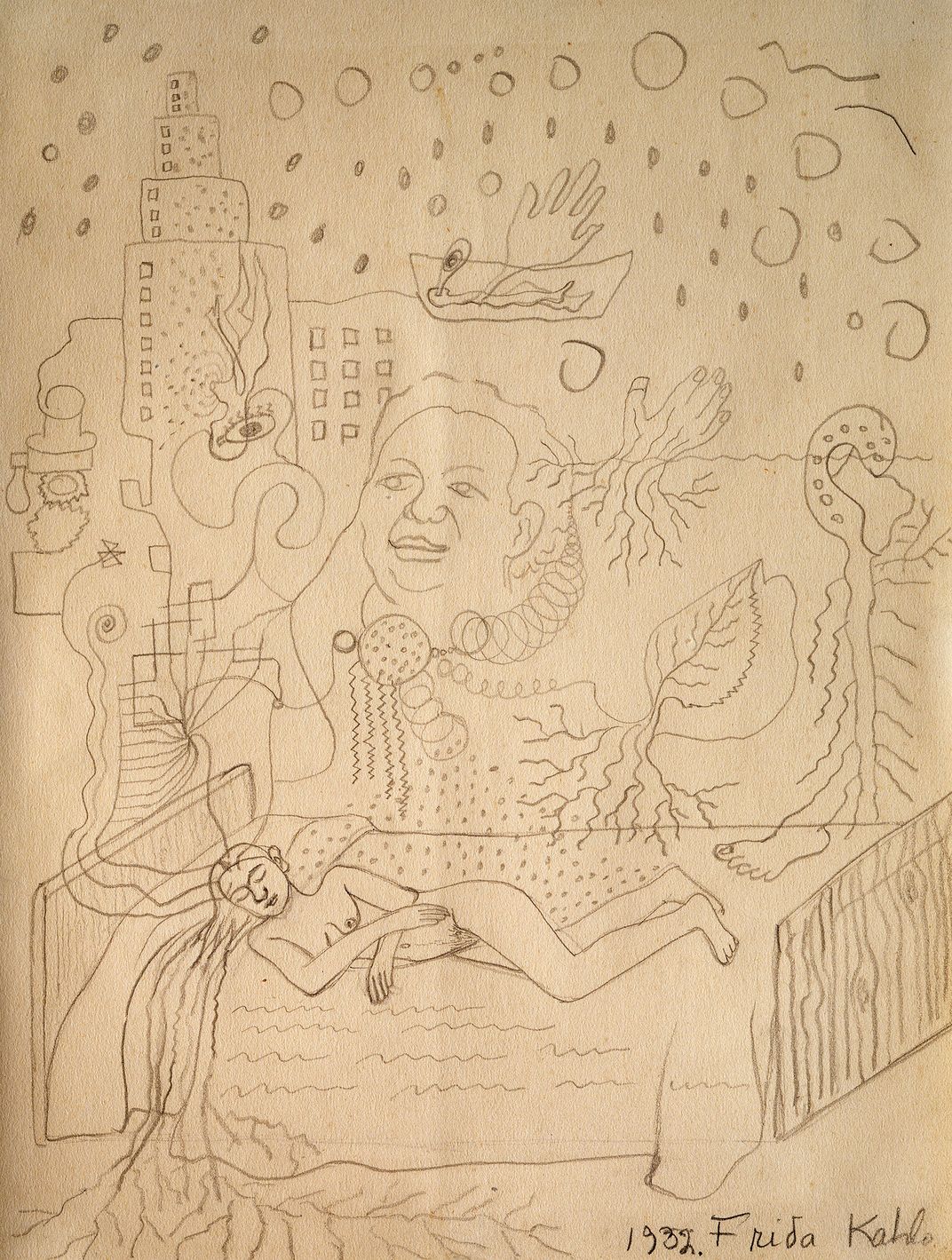

Some curators might be wary of doing a show about Kahlo devoted entirely to her use of plants—the connection might seem superficial—but when one of the garden's botanical experts made a discovery early on in the research process, Zavala knew the show was worth pursuing. Mia D’Avanza, reference librarian and exhibitions coordinator at the garden’s library, noticed that in Kahlo’s 1932 pencil-on-paper work The Dream, the artist includes an accurate drawing of one of the stages of seed germination. While Kahlo uses botanicals symbolically in many of the works on display (including a surreal painting in which the body of botanist Luther Burbank blends with that of a plant), D’Avanza was impressed by the way Kahlo drew the hook of a cotyledon, the embryonic first leaves of a seedling. For D’Avanza, this proved the artist “was not dabbling.”

The Dream is just one of more than a dozen works visitors can see at the exhibition. Zavala says she made a particular curatorial choice when bringing together the set of drawings and paintings included in the show—each depicts the complex ways Kahlo used plant imagery in her art. The works are on loan from across the U.S. as well as Mexico, an unusual feat for a botanical garden. The show also includes a recreation of Kahlo’s desk from her art studio, accurate right down to the color of the pigments she used. And the exhibition has live music, too: The Villalobos Brothers, known for blending indigenous music with jazz and classical music, will perform at several evening events throughout the next few months. (Frida Kahlo: Art, Garden, Life runs until November 1).

On top of all that, garden-goers can see art based on Kahlo’s own work but created by the garden's artist-in-residence, Mexico’s Humberto Spíndola. Spíndola’s The Two Fridas transforms a famous double-self-portrait by Kahlo into a three-dimensional installation, which includes replicas of the iconic dresses Kahlo wears in her painting rendered in fine tissue paper and displayed on traditional mannequins crafted from delicate reeds.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/michele-lent-hirsch.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/michele-lent-hirsch.jpg)