Visit the Only Village Inside the Grand Canyon

Supai is so remote, mail is delivered by mule train

If you haven’t visited the village of Supai, there’s probably a good reason: The only town inside the Grand Canyon, it’s located deep inside a 3,000-foot-deep hole. The only way to get there is by hiking, riding an animal or taking a helicopter. In fact, it’s the most remote town in the lower 48 states—and it’s well worth the inconvenience.

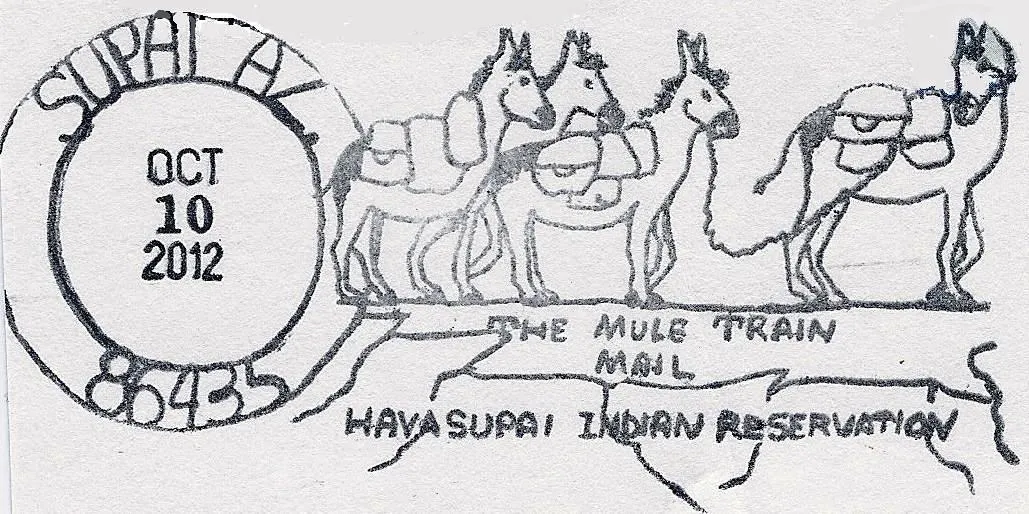

Because it’s so remote, it’s also the only place in the country that receives mail deliveries by mule. Two hundred and eight people lived in Supai Village in 2010, according to the U.S. Census, and all of them get their mail by “mule train”—a series of linked mules carrying packages and letters. Each parcel that makes it out of Supai has a special postmark—one that’s well known to backpackers, who often mail out (or mule out) their heavy packs via the postal service rather than drag them back up eight steep miles.

Supai is part of the Havasupai Indian Reservation, and the place where the Havasupai population has lived for more than 1,000 years—though the tribe has had to fight to retain the use of their own land. The name Havasupai means “people of the blue-green water,” and Havasupais have spent the last ten centuries farming and hunting within the canyon. These days, the tribe is known as much for their unusual canyon location as for their traditional cultural life and beautiful arts and crafts, especially their iconic coiled basketry.

The reservation is unique for reasons aside from its location. Whereas the U.S. government created many reservations by violently forcing tribes out of their ancestral land and then ghettoizing them in far-away places, the story of the Havasupai is a bit different. At one point, according to Indian Country Today, that land spanned 1.6 million acres—the size of the entire state of Delaware. But when Europeans and later the U.S. government began to grab Native land, they considered the unusual beauty and rich mineral content of the Havasupai region especially worth taking. By the late 19th century, tribal lands dwindled from 1.6 million acres to just 518. Havasupais were confined to the bottom of a small canyon without the plateau lands they traditionally used in winter.

The tribe appealed to Congress seven different times over the course of 66 years—until President Ford finally signed an important bill into law. As the National Park Service writes, the U.S. government added 185,000 acres to the Havasupai reservation, along with 95,000 acres of access to traditional-use lands within Grand Canyon National Park. Some areas are still under National Park Service operation, but the Havasupais can once again access some of their original plateau areas. The joyful moment when Havasupai lands were restored in 1975 remains an important one in modern Native American legal history.

Today, Supai Village is home to some of the world’s most beautiful scenery. Surrounded by red canyon walls and waterfalls, Havasupai homes and small buildings are unusually picturesque. Visitors can stay at the Havasupai Lodge or obtain camping permits. There’s also one “limited service” cafe. But although tourism makes up a large portion of the village’s income, newcomers are reminded that the canyon is a delicate one. Flash floods are common: During a major storm in 2010, 143 tourists had to evacuate and three pack horses were swept away. The village is still making some post-flood repairs. If you’re brave enough to brave the eight-mile hike (keep an eye out for mules), you’ll be richly rewarded. It’s safe to say there's no other village like it in the world.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/michele-lent-hirsch.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/michele-lent-hirsch.jpg)