Vladimir Lenin’s Return Journey to Russia Changed the World Forever

On the 100th anniversary of the Russian Revolution, our writer set out from Zurich to relive this epic travel

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1c/1f/1c1fc2fb-72a5-4916-a825-399e3f446756/mar2017_g20_leninsodyssey.jpg)

The town of Haparanda, 700 miles north of Stockholm, is a lonely smudge of civilization in the vast tundra of Swedish Lapland. It was once a thriving outpost for trade in minerals, fur and timber, and the main northern crossing point into Finland, across the Torne River. On a cold and cloudless October afternoon, I stepped off the bus after a two-hour ride from Lulea, the last stop on the passenger train from Stockholm, and approached a tourist booth inside the Haparanda bus station. The manager sketched out a walk that took me past the northernmost IKEA store in the world, and then under a four-lane highway and down the Storgatan, or main street. Scattered among the concrete apartment blocks were vestiges of the town’s rustic past: a wood-shingle trading house; the Stadshotell, a century-old inn; and the Handelsbank, a Victorian structure with cupolas and a curving gray-slate roof.

I followed a side street to a grassy esplanade on the banks of the Torne. Across the river in Finland the white dome of the 18th-century Alatornio Church rose over a forest of birches. In the crisp light near dusk I walked on to the railroad station, a monumental neo-Classical brick structure. Inside the waiting room I found what I’d been looking for, a bronze plaque mounted on a blue tile wall: “Here Lenin passed through Haparanda on April 15, 1917, on his way from exile in Switzerland to Petrograd in Russia.”

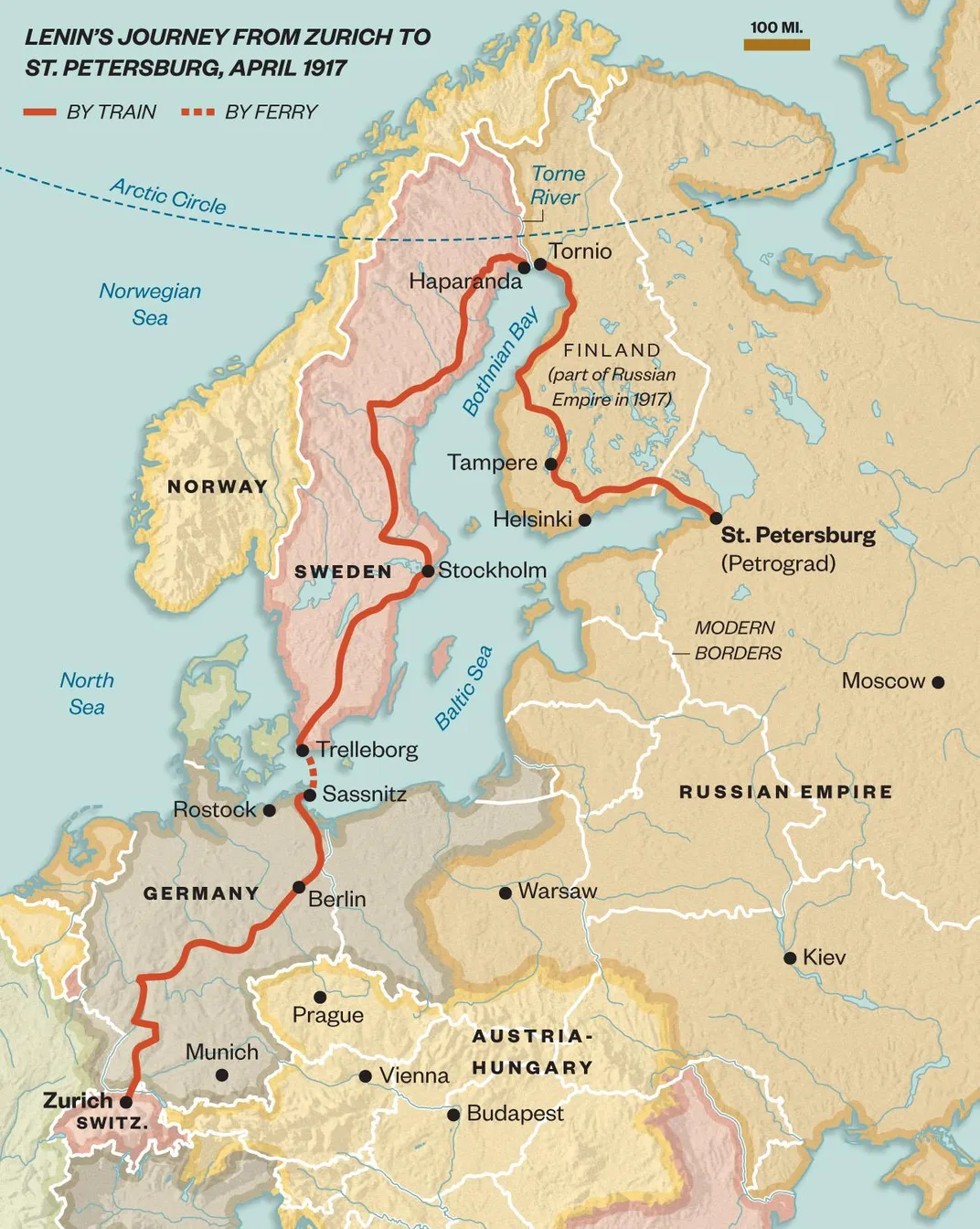

Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, joined by 29 other Russian exiles, a Pole and a Swiss, was on his way to Russia to try to seize power from the government and declare a “dictatorship of the proletariat,” a phrase coined in the mid-19th century and adopted by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, the founders of Marxism. Lenin and his fellow exiles, revolutionaries all, including his wife, Nadezhda Krupskaya, had boarded a train in Zurich, crossed Germany, traveled the Baltic Sea by ferry and ridden 17 hours by rail from Stockholm to this remote corner of Sweden.

They hired horse-drawn sleds to head across the frozen river to Finland. “I remember that it was night,” Grigory Zinoviev, one of the exiles traveling with Lenin, would write in a memoir. “There was a long thin ribbon of sledges. On each sledge were two people. Tension as [we] approached the Finnish border reached its maximum....Vladimir Ilyich was outwardly calm.” Eight days later, he would reach St. Petersburg, then Russia’s capital but known as Petrograd.

Lenin’s journey, undertaken 100 years ago this April, set in motion events that would forever change history—and are still being reckoned with today—so I decided to retrace his steps, curious to see how the great Bolshevik imprinted himself on Russia and the nations he passed through along the way. I also wanted to sense some of what Lenin experienced as he sped toward his destiny. He traveled with an entourage of revolutionaries and upstarts, but my companion was a book I’ve long admired, To the Finland Station, Edmund Wilson’s magisterial 1940 history of revolutionary thought, in which he described Lenin as the dynamic culmination of 150 years of radical theory. Wilson’s title refers to the Petrograd depot, “a little shabby stucco station, rubber gray and tarnished pink,” where Lenin stepped off the train that had carried him from Finland to remake the world.

As it happens, the centennial of Lenin’s fateful trip comes just when the Russia question, as it might be called, has grown increasingly urgent. President Vladimir Putin has emerged in recent years as a militaristic authoritarian intent on rebuilding Russia as a world power. U.S.-Russian relations are more fraught than in decades.

While Putin embraces the aggressive posture of his Soviet predecessors—the murder of oppositionists, the expansion of the state’s territorial boundaries by coercion and violence—and in that sense is heir to Lenin’s brutal legacy, he is no fan. Lenin, who represents a tumultuous force that turned a society upside down, is hardly the kind of figure that Putin, a deeply conservative autocrat, wants to celebrate. “We did not need a global revolution,” Putin told an interviewer last year on the 92nd anniversary of Lenin’s death. A few days later Putin denounced Lenin and the Bolsheviks for executing Czar Nicholas II, his family and their servants, and for killing thousands of clergy in the Red Terror, and placing a “time bomb” under the Russian state.

The sun was setting as I made my way toward the bus station to catch my ride across the bridge to Finland. I shivered in the Arctic chill as I walked beside the river Lenin had crossed, with the old church steeple reflecting off the placid water in the fading pink light. At the terminal café, I ordered a plate of herring—misidentified by the waitress as “whale”—and sat in the gathering darkness until the bus pulled up, in a mundane echo of Lenin’s perilous journey.

**********

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov was born in 1870 into a middle-class family in Simbirsk (now called Ulyanovsk), on the Volga River, 600 miles east of Moscow. His mother was well-educated, his father the director of primary schools for Simbirsk Province and a “man of high character and ability,” Wilson writes. Though Vladimir and his siblings grew up in comfort, the poverty and injustice of imperial Russia weighed heavily upon them. In 1887 his older brother, Alexander, was hanged in St. Petersburg for his involvement in a conspiracy to assassinate Czar Alexander III. The execution “hardened” young Vladimir, said his sister, Anna, who would be sent into exile for subversion. Vladimir’s high-school principal complained that the teenager had “a distant manner, even with people he knows and even with the most superior of his schoolmates.”

After an interlude at Kazan University, Ulyanov began reading the works of Marx and Engels, the 19th-century theoreticians of Communism. “From the moment of his discovery of Marx...his way was clear,” the British historian Edward Crankshaw wrote. “Russia had to have revolution.” Upon earning a law degree from St. Petersburg University in 1891, Lenin became a leader of a Marxist group in St. Petersburg, secretly distributing revolutionary pamphlets to factory workers and recruiting new members. As the brother of an executed anti-czarist, he was under surveillance by the police, and in 1895 he was arrested, convicted of distributing propaganda and sentenced to three years in Siberian exile. Nadezhda Krupskaya, the daughter of an impoverished Russian army officer suspected of revolutionary sympathies, joined him there. The two had met at a gathering of leftists in St. Petersburg; she married him in Siberia. Ulyanov later would adopt the nom de guerre Lenin (likely derived from the name of a Siberian river, the Lena).

Soon after his return from Siberia, Lenin fled into exile in Western Europe. Except for a brief period back in Russia, he remained out of the country until 1917. Moving from Prague to London to Bern, publishing a radical newspaper called Iskra (“Spark”) and trying to organize an international Marxist movement, Lenin laid out his plan to transform Russia from a feudal society into a modern workers’ paradise. He argued that revolution would come from a coalition of peasants and factory workers, the so-called proletariat—led always by professional revolutionaries. “Attention must be devoted principally to raising the workers to the level of revolutionaries,” Lenin wrote in his manifesto What Is to Be Done? “It is not at all our task to descend to the level of the ‘working masses.’”

**********

Soon after the outbreak of the world war in August 1914, Lenin and Krupskaya were in Zurich, living off a small family inheritance.

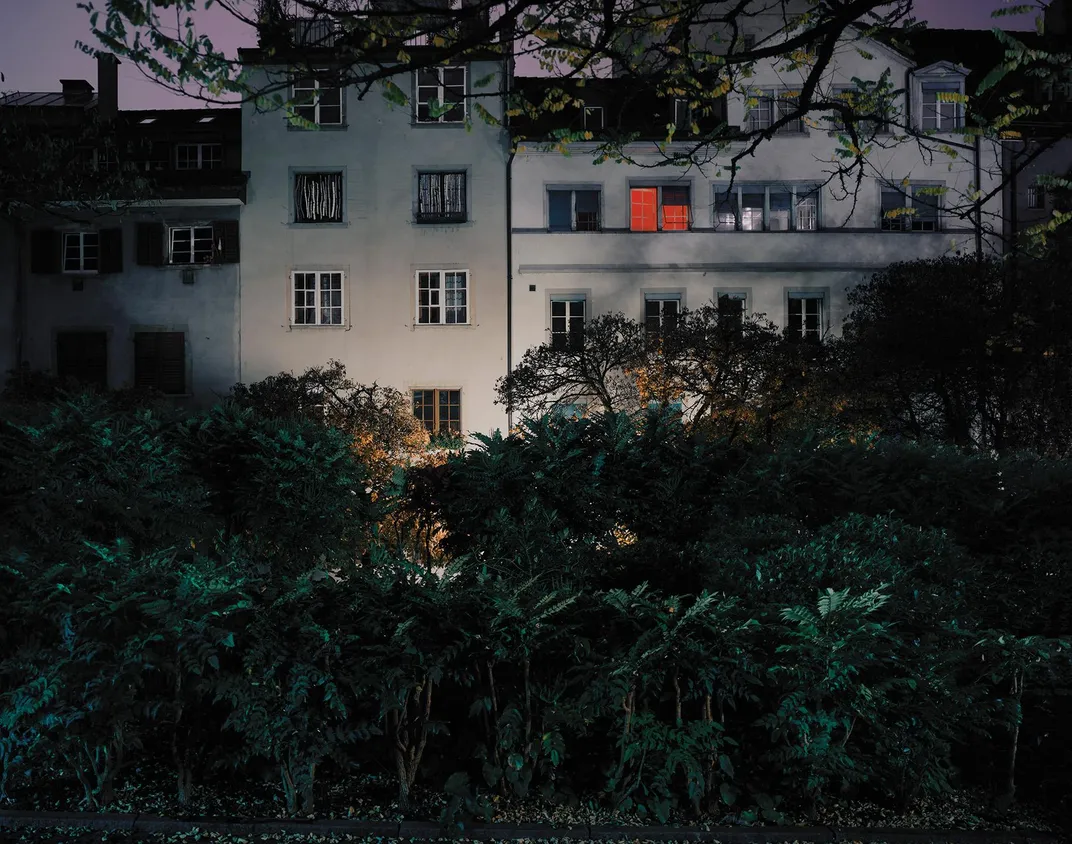

I made my way to the Altstadt, a cluster of medieval alleys that rise from the steep banks of the Limmat River. The Spiegelgasse, a narrow cobblestone lane, jogs uphill from the Limmat, winds past the Cabaret Voltaire, a café founded in 1916 and, in many accounts, described as the birthplace of Dadaism, and spills into a leafy square dominated by a stone fountain. Here I found Number 14, a five-story building with a gabled rooftop, and a commemorative plaque mounted on the beige facade. The legend, in German, declares that from February 21, 1916, until April 2, 1917, this was the home of “Lenin, leader of the Russian Revolution.”

Today the Altstadt is Zurich’s most touristy neighborhood, filled with cafés and gift shops, but when Lenin lived here, it was a down-and-out quarter prowled by thieves and prostitutes. In her Reminiscences of Lenin, Krupskaya described their home as “a dingy old house” with “a smelly courtyard” overlooking a sausage factory. The house had one thing going for it, Krupskaya remembered: The owners were “a working-class family with a revolutionary outlook, who condemned the imperialist war.” At one point, their landlady exclaimed, “The soldiers ought to turn their weapons against their governments!” After that, wrote Krupskaya, “Ilyich would not hear of moving to another place.” Today that rundown rooming house has been renovated and features a trinket shop on the ground floor selling everything from multicolored Lenin busts to lava lamps.

Lenin spent his days churning out tracts in the reading room of Zurich’s Central Library and, at home, played host to a stream of fellow exiles. Lenin and Krupskaya took morning strolls along the Limmat and, when the library was closed on Thursday afternoons, hiked up the Zurichberg north of the city, taking along some books and “two bars of nut chocolate in blue wrappers at 15 centimes.”

I followed Lenin’s usual route along the Limmatquai, the river’s east bank, gazing across the narrow waterway at Zurich’s landmarks, including the church of St. Peter, distinguished by the largest clock face in Europe. The Limmatquai skirted a spacious square and at the far corner I reached the popular Café Odeon. Famed for Art Nouveau décor that has changed little in a century—chandeliers, brass fittings and marble-sheathed walls—the Odeon was one of Lenin’s favorite spots for reading newspapers. At the counter, I fell into conversation with a Swiss journalist who freelances for the venerable Neue Zürcher Zeitung. “The paper had already been around for 140 years when Lenin lived here,” he boasted.

On the afternoon of March 15, 1917, Mieczyslaw Bronski, a young Polish revolutionary, raced up the stairs to the Lenins’ one-room apartment, just as the couple had finished lunch. “Haven’t you heard the news?” he exclaimed. “There’s a revolution in Russia!”

Enraged over food shortages, corruption and the disastrous war against Germany and Austria-Hungary, thousands of demonstrators had filled the streets of Petrograd, clashing with police; soldiers loyal to the czar switched their support to the protesters, forcing Nicholas II to abdicate. He and his family were placed under house arrest. The Russian Provisional Government, dominated by members of the bourgeoisie—the caste that Lenin despised—had taken over, sharing power with the Petrograd Soviet, a local governing body. Committees, or “soviets,” made up of industrial workers and soldiers, many with radical sympathies, had begun to form across Russia. Lenin raced out to buy every newspaper he could find—and began making plans to return home.

The German government was at war with Russia, but it nonetheless agreed to help Lenin return home. Germany saw “in this obscure fanatic one more bacillus to let loose in tottering and exhausted Russia to spread infection,” Crankshaw writes.

On April 9, Lenin and his 31 comrades gathered at Zurich station. A group of about 100 Russians, enraged that the revolutionaries had arranged passage by negotiating with the German enemy, jeered at the departing company. “Provocateurs! Spies! Pigs! Traitors!” the demonstrators shouted, in a scene documented by historian Michael Pearson. “The Kaiser is paying for the journey....They’re going to hang you...like German spies.” (Evidence suggests that German financiers did, in fact, secretly fund Lenin and his circle.) As the train left the station, Lenin reached out the window to bid farewell to a friend. “Either we’ll be swinging from the gallows in three months or we shall be in power,” he predicted.

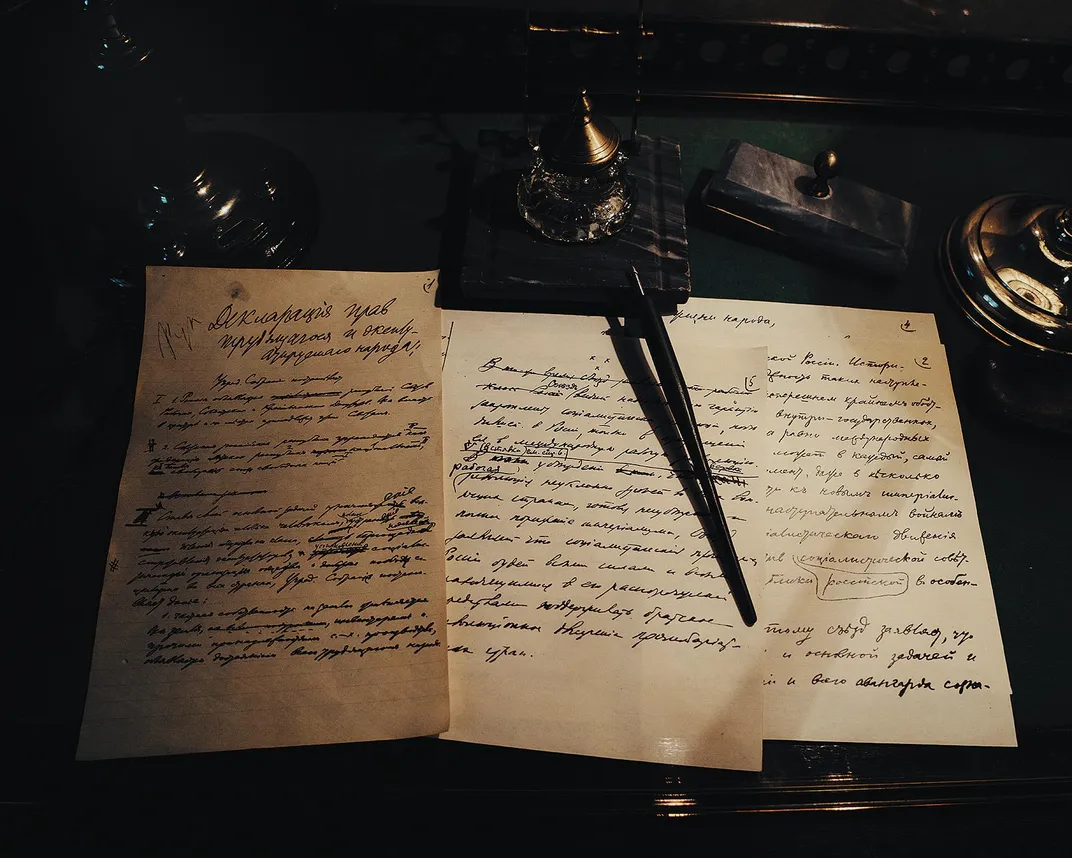

Seated with Krupskaya in an end compartment, Lenin scribbled in an exercise book, expressing views similar to those he had advanced shortly before departure, by telegram to his Bolshevik cohorts in the Petrograd Soviet, urging no compromise: “Our tactics: no support to the new government;...arming of the proletariat the sole guarantee;...no rapprochement with other parties.”

As they rolled toward Berlin, Krupskaya and Lenin took note of the absence of young men in the villages where they stopped—virtually all were at the front or dead.

**********

A Deutsche Bahn regional train second-class compartment bore me across Germany to Rostock, a port city on the Baltic Sea. I boarded the Tom Sawyer, a seven-deck vessel the length of two football fields operated by the German TT Lines. A handful of tourists and dozens of Scandinavian and Russian truck drivers sipped goulash soup and ate bratwurst in the cafeteria as the ferry lurched into motion. Stepping onto the outdoor observation deck on a cold, drizzly night, I felt the sting of sea spray and stared up at a huge orange lifeboat, clamped in its frame high above me. Leaning over the starboard rail, I could make out the red and green lights of a buoy flashing through the mist. Then we passed the last jetty and headed into the open sea, bound for Trelleborg, Sweden, six hours north.

The sea was rougher when Lenin made the crossing aboard a Swedish ferry, Queen Victoria. While most of his comrades suffered the heaving of the ship below decks, Lenin remained outside, joining a few other stalwarts in singing revolutionary anthems. At one point a wave broke across the bow and smacked Lenin in the face. As he dried himself with a handkerchief, someone declared, to laughter, “The first revolutionary wave from the shores of Russia.”

Plowing through the blackness of the Baltic night, I found it easy to imagine the excitement that Lenin must have felt as his ship moved inexorably toward his homeland. After standing in the drizzle for a half-hour, I headed to my spartan cabin to catch a few hours sleep before the vessel docked in Sweden at 4:30 in the morning.

In Trelleborg, I caught a train north to Stockholm, as Lenin did, riding past lush meadows and forests.

Once in the Swedish capital I followed in Lenin’s footsteps down the crowded Vasagatan, the main commercial street, to PUB, once the city’s most elegant department store, now a hotel. Lenin’s Swedish socialist friends brought him here to be outfitted “like a gentleman” before his arrival in Petrograd. He consented to a new pair of shoes to replace his studded mountain boots, but he drew the line at an overcoat; he was not, he said, opening a tailor shop.

From the former PUB store, I crossed a canal on foot to the Gamla Stan, the Old Town, a hive of medieval alleys on a small island, and walked to a smaller island, Skeppsholmen, the site of another monument to Lenin’s sojourn in Sweden. Created by Swedish artist Bjorn Lovin and situated in the courtyard of the Museum of Modern Art, it consists of a backdrop of black granite and a long strip of cobblestones embedded with a piece of iron tram track. The work pays tribute to an iconic photo of Lenin strolling the Vasagatan, carrying an umbrella and wearing a fedora, joined by Krupskaya and other revolutionaries. The museum catalog asserts that “This is not a monument that pays tribute to a person” but rather is “a memorial, in the true sense of the word.” Yet the work—like other vestiges of Lenin all over Europe—has become an object of controversy. After a visit in January 2016, former Swedish Prime Minister Carl Bildt tweeted that the exhibit was a “shameful monument to Lenin visiting Stockholm. At least it’s dark & discreet.”

**********

Clambering into the horse-drawn sleds on the bank of the frozen Torne in Haparanda on the night of April 15, Lenin and his wife and comrades crossed to Finland, then under Russian control, and fully expected to be turned back at the border or even detained by Russian authorities. Instead they received a hearty welcome. “Everything was already familiar and dear to us,” Krupskaya wrote in Reminiscences, recalling the train they boarded in Russianized Finland, which had been annexed by Czar Alexander I in 1809. “[T]he wretched third-class cars, the Russian soldiers. It was terribly good.”

I spent the night in Kemi, Finland, a bleak town on Bothnian Bay, walking in the freezing rain through the deserted streets to a concrete-block hotel just up from the waterfront. When I awoke at 7:30 the town was still shrouded in darkness. In winter, a receptionist told me, Kemi experiences only a couple of hours of daylight.

From there, I took the train south to Tampere, a riverside city where Lenin briefly stopped on his way to Petrograd. Twelve years earlier, Lenin had held a clandestine meeting in the Tampere Workers Hall with a 25-year-old revolutionary and bank robber, Joseph Stalin, to discuss money-raising schemes for the Bolsheviks. In 1946, pro-Soviet Finns turned that meeting room into a Lenin Museum, filling it with objects such as Lenin’s high-school honors certificate and iconic portraiture, including a copy of the 1947 painting Lenin Proclaims Soviet Power, by the Russian artist Vladimir Serov.

“The museum’s primary role was to convey to the Finns the good things about the Soviet system,” curator Kalle Kallio, a bearded historian and self-described “pacifist,” told me when I met him at the entrance to the last surviving Lenin museum outside Russia. At its peak, the Lenin Museum drew 20,000 tourists a year—mostly Soviet tour groups visiting nonaligned Finland to get a taste of the West. But after the Soviet Union broke apart in 1991, interest waned, Finnish members of parliament denounced it and vandals ripped off the sign on the front door and riddled it with bullets. “It was the most hated museum in Finland,” Kallio said.

Under Kallio’s guidance, the struggling museum got a makeover last year. The curator tossed out most of the hagiographic memorabilia and introduced objects that depicted the less palatable aspects of the Soviet state—an overcoat worn by an officer of Stalin’s secret police, the NKVD; a diorama of a Siberian prison camp. “We want to talk about Soviet society and his effect on history, and not make this a glorification thing,” said Kallio, adding that business has begun to pick up, especially among Finnish schoolchildren.

Finns aren’t alone in wanting to wipe out or otherwise grapple with the many tributes to Lenin that dot the former Soviet bloc. Protesters in the former East German city of Schwerin have battled for more than two years against municipal authorities to remove one of the last Lenin statues standing in Germany: a 13-foot-tall memorial erected in 1985 in front of a Soviet-style apartment block. In Nowa Huta, a suburb of Krakow, Poland, once known as “the ideal socialist town,” locals at a 2014 art festival raised a fluorescent green Lenin poised in the act of urination—near where a Lenin statue was torn down in 1989. In Ukraine, about 100 Lenin monuments have been removed in the last couple of years, commencing with a Lenin statue in Kiev toppled during demonstrations that brought down President Viktor Yanukovych in 2014. Even a Lenin sculpture in a central Moscow courtyard was a recent victim of decapitation.

In the morning I boarded the Allegro high-speed train at Helsinki Central Station for the three-and-a-half-hour, 300-mile trip to St. Petersburg. As I settled into my seat in the first-class car, we sped past birch and pine forests and soon approached the Russian border. A female immigration official scrupulously leafed through my U.S. passport, asked the purpose of my visit (tourism, I replied), frowned, wordlessly stamped it and handed it back to me. Shortly afterward, we pulled into the Finlyandsky Vokzal—the Finland Station.

Lenin arrived here on the night of April 16, eight days after leaving Zurich. Hundreds of workers, soldiers and an honor guard of sailors were waiting. Lenin stepped out of the small, red brick depot and climbed onto the roof of an armored car. He promised to pull Russia out of the war and do away with private property. “The people need peace, the people need bread, the people need land. And [the Provisional Government] gives you war, hunger, no bread,” he declared. “We must fight for the social revolution...till the complete victory of the proletariat. Long live the worldwide Socialist revolution!”

“Thus,” said Leon Trotsky, the Marxist theoretician and Lenin’s compatriot, “the February revolution, garrulous and flabby and still rather stupid, greeted the man who had arrived with a determination to set it straight both in thought and in will.” The Russian socialist Nikolai Valentinov, in his 1953 memoir, Encounters With Lenin, recalls a fellow revolutionary who described Lenin as “that rare phenomenon—a man of iron will and indomitable energy, capable of instilling fanatical faith in the movement and the cause, and possessed of equal faith in himself.”

I caught a tram outside the Finland Station, rebuilt as a concrete colossus in the 1960s, and followed Lenin’s route to his next stop in Petrograd: the Kshesinskaya Mansion, an Art Nouveau villa given by Czar Nicholas II to his ballet-star mistress and seized by Bolsheviks in March 1917. I’d arranged ahead of time for a private tour of the elegant block-long villa, a series of interconnected structures built of stone and brick and featuring decorative metalwork and colored tiles.

Lenin rode on top of an armored vehicle to the mansion and climbed the stairs to a balcony, where he addressed a cheering crowd. “The utter falsity of all the [Provisional Government’s] promises should be made clear.” The villa was declared a state museum by the Soviets during the 1950s, though it, too, has played down the revolutionary propaganda in the last 25 years. “Lenin was a great historical personality,” museum director Evgeny Artemov said as he led me into the office where Lenin worked daily until July 1917. “As for passing judgment, that’s up to our visitors.”

During the spring of 1917, Lenin and his wife resided with his elder sister, Anna, and brother-in-law, Mark Yelizarov, the director of a Petrograd marine insurance company, in an apartment building at Shirokaya Street 52, now Lenina Street. I entered the rundown lobby and climbed a stairwell that reeked of boiled cabbage to a carefully maintained five-room apartment crammed with Lenin memorabilia. Nelli Privalenko, the curator, led me into the salon where Lenin once plotted with Stalin and other revolutionaries. Privalenko pointed out Lenin’s samovar, a piano and a chess table with a secret compartment to hide materials from the police. That artifact spoke to events after the Provisional Government turned against the Bolsheviks in July 1917 and Lenin was on the run, moving among safe houses. “The secret police came here searching for him three times,” Privalenko said.

The Smolny Institute, a former school for aristocratic girls built in 1808, became the staging ground of the October Revolution. In October 1917 Trotsky, the chairman of the Petrograd Soviet, based here, mobilized Red Guards, rebellious troops and sailors and prepared them to seize power from the now deeply unpopular Provisional Government. On October 25, Lenin sneaked inside Smolny, and took charge of a coup d’état. “Lenin was coordinating the military attack, sending messages and telegrams from here,” said Olga Romanova, a guide at Smolny, which now houses both a museum and St. Petersburg administrative offices. She led me down a gloomy hallway to the conference room, a former dance hall where the Bolsheviks (“majority”) swept aside their socialist rivals and declared themselves in charge. “By 3 a.m. they heard that the Winter Palace had fallen, and that the government had been arrested.” Barely six months after his return to Russia, Lenin was the absolute ruler of his country.

**********

The man who dreamed of creating an egalitarian society, in fact dealt ruthlessly with anyone who dared oppose him. In his “attitude to his fellow-men,” the Russian economist and one-time Marxist Pyotr Struve wrote in the 1930s, “Lenin breathed coldness, contempt and cruelty.” Crankshaw wrote in a 1954 essay that Lenin “wanted to save the people from the dreadful tyranny of the czars—but in his way and no other. His way held the seeds of another tyranny.”

Memorial, the prominent Russian human rights group, which has exposed abuses under Putin, continues to unearth damning evidence of crimes by Lenin that the Bolsheviks suppressed for decades. “If they had arrested Lenin at the Finland Station, it would have saved everyone a lot of trouble,” historian Alexander Margolis said when I met him at the group’s cramped, book-lined offices. Communiqués uncovered by Russian historians support the idea that Lenin gave the direct order for the execution of the czar and his immediate family.

When the civil war began in 1918, Lenin called for what he termed “mass terror” to “crush” resistance, and tens of thousands of deserters, peasant rebels and ordinary criminals were executed over the next three years. Margolis says that the Soviet leadership white-washed Lenin’s murderous rampage to the end of its 74-year rule. “At Khrushchev’s Party Congress in 1956, the line was that under Lenin all was fine and Stalin was a pervert who spoiled it all for us,” he says. “But the scale of bloodshed, repression and violence was not any different.”

In spite of such revelations, many Russians today view Lenin nostalgically as the founder of a powerful empire, and his statue still rises over countless public squares and private courtyards. There are Lenin prospekts, or boulevards, from St. Petersburg to Irkutsk, and his embalmed corpse—Lenin died of a brain hemorrhage in 1924 at age 53—still lies in its marble mausoleum beside the Kremlin. It’s one of the many ironies of his legacy that even as elite Russian troops guard his tomb, which hundreds of thousands of people visit annually, the government doesn’t quite know how to evaluate or even recognize what the man did.

In his 1971 appraisal of To the Finland Station, Edmund Wilson acknowledged the horrors unleashed by the Bolshevik revolutionary—a darkness that has endured. “The remoteness of Russia from the West evidently made it even easier to imagine that the [aim of] the Russian Revolution was to get rid of an oppressive past,” he wrote. “We did not foresee that the new Russia must contain a good deal of the old Russia: censorship, secret police...and an all-powerful and brutal autocracy.”

As I had crossed Sweden and Finland, watching the frozen ground flash by hour after hour, and crossed into Russia, I envisioned Lenin, reading, dispatching messages to his comrades, looking out at the same vast skies and infinite horizon.

Whether he hurtled toward doom or triumph, he couldn’t know. In the last hours before I arrived at the Finland Station, the experience grew increasingly ominous: I was following, I realized, the trajectory of a figure for whom the lust for power and ruthless determination to raze the existing order overtook all else, devouring Lenin, and sealing Russia’s fate.

**********

After the fall of the Soviet Union, St. Petersburg’s mayor, Anatoly Sobchak, set up his headquarters in the Smolny Institute. In this same building, just down the hall from Lenin’s old office, another politician with a ruthless style and a taste for authoritarianism was, from 1991 to 1996, paving his way to power: Deputy Mayor Vladimir Putin.

Now, on the eve of the centenary of the October Revolution that propelled Lenin to power, Putin is being called upon to pass definitive judgment on a figure that, in some ways, prefigured his own rise.

“Lenin was an idealist, but when he found himself in the real situation, he became a very evil and sinister person,” said Romanova, leading me into Lenin’s corner study, with views of the Neva River and mementos of the five months he lived and worked here, including his trademark worker’s cap. She had “heard nothing” from her superiors about how they should commemorate the event, and expects only silence. “It’s a very difficult subject for discussion,” she said. “Nobody but the Communists knows what to do. I have an impression that everybody is lost.”

Related Reads

Essential Works of Lenin: "What Is To Be Done?" and Other Writings

To the Finland Station: A Study in the Acting and Writing of History (FSG Classics)

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2021-09-15_at_12.44.05_PM.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/41/d3/41d3b8a0-2d9a-405d-9150-93457cf602be/mar2017_g02_leninsodyssey.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2021-09-15_at_12.44.05_PM.png)