Vuvuzela: The Buzz of the World Cup

Deafening to fans, broadcasters and players, the ubiquitous plastic horn is closely tied to South Africa’s soccer tradition

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/vuvuzela-South-Arfrica-631.jpg)

Players taking to the pitch for the World Cup games in South Africa may want to pack some extra equipment in addition to shinguards, cleats and jerseys: earplugs.

The earplugs will protect against the aural assault of vuvuzelas. The plastic horns are a South African cultural phenomenon that that when played by hundreds or thousands of fans, sounds like a giant, angry swarm of hornets amplified to a volume that would make Ozzy Osbourne flinch. South African fans play the horns to spur their favorite players into action on the field.

“It’s really loud,” says John Nauright, professor of sports management at George Mason University and the author of “Long Run to Freedom: Sport, Cultures and Identities in South Africa.” “You can walk around with a pretty massive headache if you’re not wearing earplugs.”

A study in the South African Medical Journal released earlier this year said fans subjected to the vuvuzela swarm were exposed to a deafening peak of more than 140 decibels, equivalent to standing near a jet engine. The South African Association of Audiologists has warned they can damage hearing.

Noisemakers at soccer matches have a long history. Drums and chants are favored in countries like Brazil, where one of the popular teams has about two dozen distinct chants or anthems. Wooden rattles began making a racket at British soccer games in the early 1900s, a tradition that continued until the 1960s when fans began to chant and sing instead. Now there are dozens of new songs and chants seemingly every week. Some are adaptations of popular songs or old hymns. Some are profane taunts of their opponents.

Thundersticks emerged in Korea in the 1990s and provided the booming background for the 2002 World Cup in that country. (Thundersticks also made a brief appearance in the United States, most notably during the Anaheim Angels’ playoff run during the 2002 Major League Baseball postseason.)

In South Africa over the past decade, the plastic horns have become an integral part of the choreography at matches and the culture of the sport. When South Africa won its bid to host the World Cup in May 2004, Nelson Mandela and others celebrated with vuvuzelas. More than 20,000 were sold that day. It’s not just loud, but cheap (they cost about $7), and it has become ubiquitous at South African soccer matches. The official marketing company for the horns says it has received orders for more than 600,000 in recent months.

“This is our voice,” Chris Massah Malawai told a South African newspaper earlier this year while watching the national team, Bafana Bafana (The Boys, The Boys), play. “We sing through it. It makes me feel the game.”

After the 2009 Confederations Cup soccer matches in South Africa, FIFA, the governing body for the World Cup, received complaints from multiple European broadcasters and a few coaches and players who wanted the vuvuzela banned. Fans on both sides argued heatedly on soccer blogs and web sites. Facebook pages both to ban the instruments and support them sprang up. One opponent in a South African newspaper suggested opening the World Cup with a vuvuzela bonfire. Others staunchly defended their beloved instruments. “The vuvuzela is in our blood and is proudly South African,” one wrote in a Facebook discussion. “They should leave us alone. It’s like banning the Brazilians from doing the samba.”

During a friendly match between South Africa and Colombia two weeks before the World Cup, officials tested noise levels at the 90,000-seat Soccer City Stadium in Johannesburg and announced there would be no ban.

The horns, FIFA officials said, were too much a part of the South African tradition to silence them. “It’s a local sound, and I don’t know how it is possible to stop it,” Joseph S. Blatter, FIFA’s president, told reporters. “I always said that when we go to South Africa, it is Africa. It’s not Western Europe. It’s noisy, it’s energy, rhythm, music, dance, drums. This is Africa. We have to adapt a little.”

The horn began showing up at matches in Soweto in the 1990s between the Kaizer Chiefs and the Orlando Pirates, rivals and the two most popular South African teams. Kaizer Motaung, a South African who played in the North American Soccer League in the mid-1970s, founded the Chiefs and began promoting the horn. The vuvuzela was introduced at their games in the 1990s with gold horns for Chiefs’ fans and black or white for Pirates’ fans.

“The [two teams] have a huge following all over the country,” Nauright says. “In fact, that game is probably still more watched than the Bafana Bafana, when the national team plays.”

Playing the horns to encourage teams to the attack became part of the culture, a way for fans to express themselves, much the way South American soccer fans drum during games. “There is a grass roots organic culture out of the townships using soccer as a way to be creative in a society that oppressed people on a daily basis,” Nauright says.

In Cape Town, a music educator, Pedro Espi-Sanchis, created a vuvuzela orchestra in 2006 that plays regularly at matches of the Bloemfontein Celtic club. Some of the songs are set to dancing and singing. “For guys who know how to play it really well, you have a technique, almost like a didgeridoo. You use the tongue to make different sounds,” Nauright says.

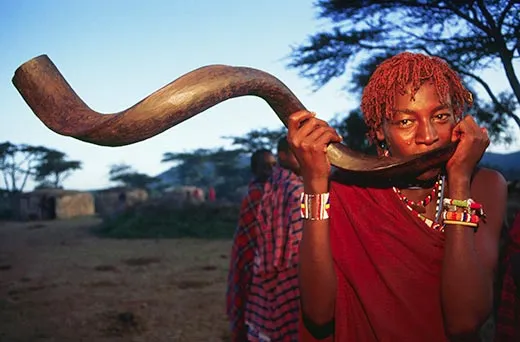

The origin of the vuvuzela is murky. Nauright explains that some people have promoted it as a modern incarnation of the traditional kudu horn used to call villagers to gatherings. But he also says horns were used in Cape Town and Johannesburg to call customers to fish carts. Early versions were made of aluminum or tin. It wasn’t until a manufacturer, Masincedane Sport, received a grant in 2001 to supply soccer stadiums with plastic horns that it exploded in popularity.

Now, they’re inescapable. The only other country where horns are heard so extensively at soccer matches is Mexico. And guess what? South Africa and Mexico meet in the World Cup opener.

“It’s sure to be the loudest match at the World Cup,” Nauright says.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/jim-morrison-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/jim-morrison-240.jpg)