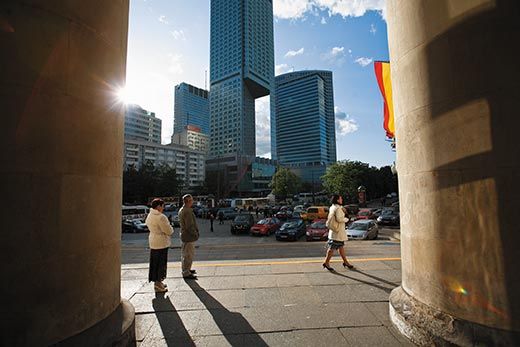

Warsaw on the Rise

A new crop of skyscrapers symbolizes the Polish capital’s effort to rebuild its downtrodden image

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/warsaw-construction-631.jpg)

It was as a student in Paris looking for a cheap travel adventure during Christmas break that I got my first glimpse of Warsaw. I had signed up with a couple of friends for a trip into Poland’s Tatra Mountains, and our second-class compartment on the night train was oppressively overheated until, shortly after midnight, cars holding Red Army officers were added in East Berlin, and the heat ceased entirely for the rest of us.

Shivering and miserable, I disembarked before dawn at a bleak platform swept by fine needles of icy snow, backlit by large military-style floodlights on lofty stanchions. It was 1961. The air smelled of low-octane gasoline, the signature scent of urban Eastern Europe in those days. Warszawa, the big station signs read. The atmosphere was eerily gulag.

Many trips over the years only confirmed my initial impression: gray, patched together and woebegone, Warsaw was an ugly misfit compared with the timeless beauties of Rome, Paris and Stockholm or, closer by, the three fabulous Austro-Hungarian gems of Vienna, Prague and Budapest.

There was good reason for Warsaw’s pitiable state. Before World War II, it had been a parklike city, a picture postcard of old-world Central European architecture on a human scale. But beginning in 1939, in the war’s opening days, the city suffered grievously from Nazi shelling and the terror bombing that targeted residential areas. The Nazis would destroy the Jewish ghetto, and more than 300,000 of its residents would die of starvation or disease or in death camps. As the war ground toward its final act, Hitler—enraged by the Polish Home Army’s general insurrection, during which more than 200,000 Poles were killed—ordered Warsaw to be physically erased. Over three months in 1944, the Nazis expelled the city’s 700,000 remaining residents and leveled nearly all of what still stood: incendiary and dynamite squads moved from building to building, reducing them to rubble or, at best, charred shells.

No other city in Europe—not even Berlin or Stalingrad—was taken down so methodically. Rebuilding in haste with the poor materials and primitive equipment available in the dreary postwar days of Soviet domination, Varsovians reclaimed a bit of their history by painfully recreating, stone by stone, the beautiful Old Town section, the elegant Royal Route leading to it, the Market Square and the Royal Castle. But the rest of the city grew into a generally undistinguished low-rise sprawl, some of it the patched-up remains of the rare buildings that escaped complete destruction, some re-creations of what had existed before, but mostly quick-lick solutions for a returning population in desperate need of shelter, offices and workshops. Little did anyone suspect that half a century later Warsaw’s agony would serve as an unexpected advantage over other major European cities: since it was no longer an open-air museum of stately mansions, cathedrals and untouchable historical monuments, the city could be molded into a dashing showcase of contemporary architecture.

In the meantime, though, postwar Poland was threadbare, excruciatingly poor, trammeled by the economic absurdities of Marxist ideology and totally in thrall to the Soviet Union. Between 1952 and 1955, Moscow dispatched several thousand Russian workers to give Warsaw its “Eiffel Tower”: the Joseph Stalin Palace of Culture and Science, a massive confection of tan stonework 42 stories high. At 757 feet, it is the tallest building in Poland (and is still the eighth highest in the European Union) and resembles an oversize wedding cake. It was billed as a fraternal gift from the Soviet people, but it sent a different message: we are bigger than you will ever be, and we are here forever. Big Brother, indeed.

I can’t count the number of Poles who told me the old saw about the palace’s observation platform being the most popular site in Warsaw because it’s the only spot from which you couldn’t see the palace. Even when Stalin’s name was lifted three years after the murderous despot died, Varsovians detested the palace for the political statement it made and for its gaudy hugeness. After 1989, the year the Berlin Wall came down, signaling Communism’s fall, younger citizens began to view it with the sort of grudging acceptance that one might feel toward a doddering but harmless old relative.

But what to do about it? In the euphoria of the early days of freedom from the Soviets, many assumed the palace would soon meet a wrecker’s ball. But it is in the very heart of downtown Warsaw—in a way it was the heart of downtown Warsaw—and it contains offices, theaters, shops, museums, a swimming pool, a conference center, even a nightclub. It had its uses. The answer was a cold war-style compromise: peaceful coexistence.

Under the Communist regime, construction had begun on the first rival to the palace: a 40-story, glass-fronted hotel and office building completed in 1989. By then, Eastern Europe was changing with dizzying speed. In Warsaw, five decades of repressed entrepreneurial energies had been released like an explosion, and soon shiny new buildings were mushrooming from one end of the city to the other. Seizing the freedom to speculate, developers threw up office and apartment blocks of dubious quality, inevitably heavy on the basic glass box cliché. Before, people had worried about what to do with the palace; now they worried about what was happening around it.

Poland, the biggest and most populous of the USSR’s former European satellites, was taking to capitalism like a Labrador pup to a muddy puddle, and the largely underdeveloped country was a good bet for future profits. Eager to secure a foothold and capitalize on low wages and high levels of skill, foreign firms rushed in. Company headquarters of a quality that would not be out of place in New York or Frankfurt began going up.

By 2004, when Polish membership in the European Union was sealed (the nation had joined NATO in 1999), the flow of foreign capital had turned into a flood. Warsaw boomed. Lech Kaczynski, mayor from 2002 to 2005, parlayed his headline-grabbing ways into the nation’s presidency. (Kaczynski died in a plane crash last April.) The current mayor, an economist and former academic named Hanna Gronkiewicz-Waltz, set out to reshape the mutilated city’s downtown area, promising not simply to modernize the city but turn it into Central and Eastern Europe’s principal financial address.

“We will change the downtown,” she declared after taking over in 2006. “In the Parade Square area, skyscrapers will be built, which will become our city’s new pride.” Everyone knew what that meant: the square is home to the palace. The time had come to bring on the “starchitects.”

Gronkiewicz-Waltz knew that she could not turn Warsaw into a futuristic never-never land like Dubai or Abu Dhabi—there was too much urban history to cherish and too little oil underfoot to pay for vastly ambitious projects—but international architects and promoters could make the city’s heart glitter. “Warsaw must grow up if it wants to compete with other big European cities,” the mayor said. She meant “up” literally.

One illustrious architect had already made his mark on the city. Norman Foster’s sober Metropolitan Building, inaugurated in 2003, was a mere seven stories high but something to behold: three cornerless, interconnected wedges, each with its own entryway, their facades punctuated by protruding granite fins that seemed to change color according to the brightness of the sky and the position of the sun. It proved to be a surprise hit with ordinary Varsovians—even parents with bored children. With a crowd-pleasing circular courtyard filled with shops, restaurants, shade trees and a fountain, the building boasts amusement park flair. A ring of 18 water jets set into the granite pavement and activated by high-pressure pumps sends spurts to varying heights, leading to a socko 32-foot burst.

But the Metropolitan was only the beginning. “We intend to build skyscrapers, yes,” says Tomasz Zemla, deputy director of Warsaw’s Department of Architecture and City Planning. “To be honest, we want to show off.”

An architect himself, Zemla presides over the city’s future in a spacious, high-ceilinged office in the central tower of the Palace of Culture and Science. “We need to get the chance to compete with Prague, Budapest and maybe even Berlin,” he says, “because it is our ambition to become an important financial center in this part of Europe. Capital in Poland is very dynamic, very strong.” As for the palace, he continues, “We can’t let it be the most important building anymore. You know, it’s still the only really famous building in Poland. Children see it as the country’s image. We need to compete with that. We have to show our ideas. We have to do bigger and better.”

To anyone who roamed the barren city in the ‘60s, ‘70s and ‘80s searching vainly for a decent café or restaurant—endlessly importuned by hustlers on the sidewalks, prostitutes in hotel lobbies and pettifogging officials at the airport—today’s Warsaw is an astonishing contrast. The city teems with shops, cafés, bars, restaurants and consumer services. A passion for trade has bred an orgy of commercial graphics—taxis and buses virtually disappear under advertisements, entire building fronts are hidden by roll-down canvas billboards. Young men and women on the crowded sidewalks chatter in the chewy syllables of their Slavic tongue, inevitably larded with Americanisms and computerese like the beguiling zupgradowac (to improve), derived from “upgrade.” Just across the street from the palace, the Zlote Tarasy (Golden Terraces) mall, opened in 2007, provides shelter from the elements under an enormous, impudently weird, silvery blanket of undulating triangular glass panes (like some ectoplasmic creature from the deep heaving up and down to catch its breath). In a vast central space escalators zoom the iPod generation to every chain store and fast-food joint that the world’s marketing geniuses could dream of. Dour, drab old Warsaw is turning into a polychrome butterfly.

Among the first starchitects to seriously challenge the dominance of the Palace of Culture was Helmut Jahn of Chicago, creator of One Liberty Place in Philadelphia and the spectacular Sony Center in Berlin. His elegantly classical Residential Tower Warsaw, 42 floors of apartments and commercial space, is now under construction just a block behind the old Soviet rock pile.

Closer still will be Zlota 44 at its completion. This blue-tinted, 54-story luxury residential complex is the brainchild of the Polish-born American Daniel Libeskind, designer of the Jewish Museum in Berlin and the original master plan for rebuilding the Ground Zero site in New York City. It features a dramatic arc of steel and glass swooping away as if seeking escape from the conventional, square-cornered structure to which it is attached (some calculated symbolism there). It was interrupted in mid-construction by a lawsuit filed by local residents who objected to their loss of sunlight and views. Final permission to complete the building was not delivered until October of last year.

Zlota’s stop-and-start progress is typical of the obstacles facing any ambitious administration in a hurry, but Warsaw had the further bad luck to be in full stride when the world banking crisis hit and credit dried up. Suddenly the grandest project of all—Zaha Hadid’s Lilium Tower—was menaced.

Hadid, an Iraqi-born British architect, planned a structure that would dominate the skyline once and for all—the first building in Warsaw to be higher than the palace. Her proposed tower of some 850 feet is destined for a site opposite the main railroad station. Gracefully curved, bowed outward in the middle and tapering at the top and bottom, Lilium’s four wings inescapably evoke horticultural images. There’s not a square line visible, and the building makes a stunning contrast to the palace’s plodding right angles and heavy decorations.

“I love that shape,” says Zemla, before extolling all three of his pet projects: “They’re beautiful.” Unfortunately, though, he and the rest of Warsaw will have to wait to see the Lilium grow. For the moment, the developers have put the project on hold until the economy improves.

Inevitably, some people would dispute Gronkiewicz-Waltz’s belief that skyscrapers are the ticket. Disdaining the race for postmodern glamour, an articulate minority calls for the city to seek instead to recapture the homey atmosphere of Middle Europe before World War II, sometimes idealized as a place of comfortable, easy living, of cobbled streets with friendly little shops, open-air markets and tree-shaded sidewalk cafés.

“When we got our freedom in 1989, I thought we would finally have real quality architecture for human society’s needs,” says Boleslaw Stelmach, an architect specializing in building in historic areas. “Instead, I found myself working in a huge office, not doing architecture but producing buildings like a factory. Well, I would rather see wiser than taller.”

Certainly Warsaw of the late ‘30s was a place of sharp intellectual activity, avant-garde theater, poetry readings, Chopin recitals and the like, but some critics of the skyscraper movement go further than Stelmach and overly romanticize the city’s past. The old Warsaw was not necessarily a civic paragon. There were also poverty, discord and social injustice—the same dark underside as any urban center.

Still, Warsaw’s long history of oppression by Russians and Germans, the terrible efficiency of its destruction and its dogged persistence in reclaiming the past make it a place apart: a city that has been obliged to reinvent itself. Even as the aesthetes and the philistines argue about what it should become, that reinvention continues. Remarkably enough, a sensible compromise seems to be falling into place.

“Yes, the center of Warsaw is going to be skyscraper city,” says Dariusz Bartoszewicz, a journalist specializing in urban matters at the Gazeta Wyborcza. “That’s its destiny. Twenty or 30 of them will be built for sure. Not in the next five years, but over time. It will happen.”

At the city’s fringes, a second wave of innovative design is beginning to reshape the Vistula River’s largely undeveloped banks. The Warsaw University Library is not only low, a mere four stories high, but meant to disappear. Topped by a 108,000-square-foot roof garden and draped with climbing plants whose greenery melds into the green of oxidized copper panels on the building’s facade, this ultramodern repository for two million books is what happens when architects are willing to share glory with a gardener.

The lead architect, Marek Budzynski, is a renowned university professor, but the landscape architect, Irena Bajerska, was virtually unknown until she was brought onto the design team. Her garden has become so popular it is now part of the regular Warsaw tourist routes. Bajerska beams and points out the young couples suited up in their tuxedos, white dresses and veils posing within her foliage for formal wedding photographs, while kids romp on the winding paths and retirees take their ease, reading newspapers and enjoying views of the city and the river.

Across the street, low-rise, riverfront apartment buildings are going up, and a series of planned projects, beginning with the Copernicus Science Center, next to the library, will perpetuate the human-scale development along the riverbank: bicycle, pedestrian and bridle paths, pleasure boat wharves and reconstruction of the Royal Gardens below historic Old Town.

“Warsaw is now in the middle of great, great things going on,” Wojciech Matusik assures me as he sips a drink in the posh bar of the Bristol Hotel, a five-minute walk from Norman Foster’s Metropolitan Building. Formerly the city’s director of planning, Matusik was once in charge of development, a position that allowed him to anticipate much of what is happening today.

I had frequented the Bristol in the ‘70s when it was a shabby, down-at-the-heels palace way past its prime (and I had known Matusik when he was a modestly paid functionary). Now renovated, the Bristol is one of Warsaw’s finest hotels, and Matusik, elegantly tailored, today a real estate consultant, is right at home. The man and the hotel have both prospered, and illustrate the distance Warsaw has come since I first passed through here 50 years ago.

“The past is very heavy here,” said Bogna Swiatkowska, a young woman who founded an organization to bring art and artists to public places. “So much happened here—World War II, the ghetto, the uprising and everything after. We live with ghosts in Warsaw, but it’s a very special place with wonderful, talented, creative people. Now it’s time to get rid of the ghosts, make our peace with the past, and think about the future.”

Rudolph Chelminski is author of The Perfectionist: Life and Death in Haute Cuisine. Tomas van Houtryve, a photographer on his first assignment for Smithsonian, lives in Paris.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.