Watching Water Run

Uncomfortable in a world of privilege, a novelist headed for the hills

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/mytown-nov06-388.jpg)

It is the hot, dark heart of summer in this small town that I love. Fireworks have been going off sporadically for several nights, and the teenagers next door are playing water polo in the afternoons in the swimming pool their professor parents built for them this year.

Down the street a 4-year-old girl is riding her tricycle madly around the circular driveway of her parents' home. It seems only yesterday that I walked by the house one morning and saw a pink ribbon on the mailbox. Now she is a tricycle racer, her long curly hair hanging rakishly down over her eyes, her concentration and speed all you need to know about the power of our species.

Last week the painting contractor who painted the exterior of my house gave me a discount for my patience while he had a stent put in an artery leading to his heart. (The attending nurse in the surgery is my weekend workout partner. She also attended the emergency surgery that saved the life of the Game and Fish genius who traps squirrels for me when they eat the trim on my house.) During the prolonged painting job, I took to spending the part of the afternoons when I would normally be taking a nap down at a nearby coffee shop reading newspapers and drinking herbal tea. I ran into the president of a local bank who has recently retired to devote himself to building a natural science museum and planetarium in Fayetteville. We already have plenty of dinosaurs. Some farseeing biologists at the University of Arkansas collected them years ago. They have been saved in a small, musty museum on the campus that was recently closed, to the ire of many of the professors. (There is always plenty of ire in a college town, accompanied by a plethora of long-winded letters to the editors of local newspapers and magazines. Nuclear power, pollution, cruelty to animals, war and cutting down trees are contenders for space, but the closing or shutting down of anything at the university is a top contender.)

Fayetteville now has 62,000 people, but it still seems like the much smaller place I found when I was 40 years old and adopted as my home. I had driven up into the northwest Arkansas hills to spend a semester in the writing program at the University of Arkansas, where I now teach. The moment I left the flatlands and began to climb into the Ozark Mountains, I fell in love with the place. There is a welcoming naturalness to the land, and it is reflected in the people. I immediately felt at home in Fayetteville and I still feel that way. Even when I didn't know everyone in town, I felt like I knew them. I lived in small towns in southern Indiana and southern Illinois when I was young, and Fayetteville has always reminded me of those places. There are many people here from the Deep South, but the heart of the place belongs to the Midwest. It is hill country, surrounded by farmland. There are never aristocracies in such places. There aren't enough people to be divided into groups. In the schools of small Midwestern towns, the only aristocracies are of beauty, intelligence and athletic prowess. I had been living in New Orleans, in a world of privilege, and I was never comfortable there. I have lived most of my life in small towns, and I'm in the habit of knowing and talking to everyone.

But I think it is the beauty of the hill country that really speaks to my heart. My ancestors are highland Scots, and my father's home in north Alabama is so much like northwest Arkansas I have the same allergies in both places. Besides, I like to watch water run downhill. After years in the flatlands, I am still delighted at the sight of rain running down my hilly street after a storm. I also like to watch it run down steep steps, before you even get to the thrill of camping north of here and watching it run over real waterfalls near the Buffalo River.

Most of all, this is where I write. Ever since the first night I spent in this town, I have been inspired to write by being here. When people in my family ask me why I live so far away from all of them, I always answer, because it's where I write. The place closes around me and makes me safe and makes me want to sing.

After 30 years of living here, I think I know everyone in town. I cannot walk down a street without seeing people I know or passing places where things occurred that mattered to me. Some of the people I loved have died, but it seems they have never left the place. Their children and grandchildren are here and their legacies: in buildings and businesses or in the town's collective memory. Some are remembered in statues and plaques, and some for things they said or wrote, and others for the places where they walked and lived. People love each other here. It's a habit and a solace in times of trouble.

I live in a glass-and-stone-and-redwood house built by an architect who won the Gold Medal of the American Institute of Architects. I bought the house for a pittance several years before he won the award, and I spend my spare time keeping it in working order. It is on two acres of land. I have deer on the lot behind the house and enough squirrels and turtles and rabbits and foxes and coons and possums to supply several petting zoos. Not to mention crows and redbirds and mockingbirds and woodpeckers and bluebirds and robins and an occasional itinerant roadrunner.

The first novel I wrote was set in Fayetteville, using many of the real people and places as background for the adventures of a poorly disguised autobiographical heroine named Amanda McCamey. (I disguised her by making her thinner, kinder and braver than I was at the time.) The novel was really about Fayetteville:

Fayetteville, Arkansas. Fateville, as the poets call it. Home of the Razorbacks. During certain seasons of the year the whole town seems to be festooned with demonic red hogs charging across bumper stickers, billboards, T-shirts, tie-clasps, bank envelopes, quilts, spiral notebooks, sweaters. Hogs. Hog country. Not a likely place for poets to gather, but more of them keep coming every year. Most of them never bother to leave. Even the ones that leave come back all the time to visit.

Fateville. Home of the Hogs. Also, poets, potters, painters, musicians, woodcarvers, college professors, unwashed doctors, makers of musical instruments....

Amanda had fallen in love with the world where the postman makes stained glass windows, the Orkin man makes dueling swords, the bartender writes murder mysteries, the waitress at the Smokehouse reads Nietzsche on her lunch break.

"Where in the name of God are you going?" everyone in New Orleans kept asking Amanda.

"To Fayetteville, Arkansas," she replied. "My Paris and my Rome."

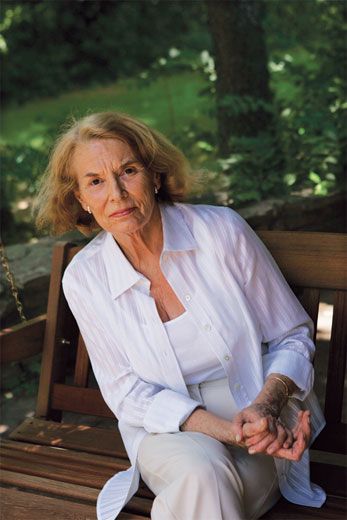

Ellen Gilchrist's 20 books include, most recently, The Writing Life, and the short story collection Nora Jane.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.