In a Small Village High in the Peruvian Andes, Life Stories Are Written in Textiles

Through weaving, the women of Ausangate, Peru, pass down the traditions of their ancestors

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d8/1f/d81f9968-f013-4348-8cf4-877b21b0d215/sqj_1507_inca_weaving_01-for-web.jpg)

In the shadow of the 20,800-foot snow-clad peak of Ausangate in the southern Peruvian Andes, Maria Merma Gonzalo works at her loom, leaning back on a strap around her waist, just as her ancestors have done for centuries. She uses a wichuna, or llama bone pick, to weave the images of lakes, rivers, plants, condors and other symbols of her life into the colorful alpaca fabric she is making. For Maria and the Quechua people, Ausangate encompasses far more than its distinction as the highest peak in southern Peru; it is a mountain spirit, or apu, held sacred since Inca times. “Because of Ausangate,” she says, “we all exist. Thanks to Ausangate, there are plenty of animals and food. We give him offerings, and he gives us everything in return.”

Her weavings capture both the sacred and everyday symbols of life in Pacchanta, a small village 80 miles southeast of Cusco. She and other Quechua women place the stories of their lives into textiles, communicating and preserving important cultural traditions. This is how memories are most vividly remembered.

For many centuries textiles have been an integral part of Quechua daily life, from birth to death. Babies are wrapped with thick belts, covered with cloth and carried on their mother’s backs in handwoven carrying cloths. Three- and four-year-olds learn to spin yarn. By eight, girls start weaving belts and soon move on to more complicated textiles, such as llicllas (women’s shoulder cloths), ponchos and kaypinas (carrying cloths).

Pacchanta is a stable community blessed by its proximity to cold, mountain glaciers, their mineral-rich runoff irrigating fields that yield particularly flavorful potatoes for making chuño, or freeze-dried potatoes. At 14,500 feet, villagers live in stone and sod houses, although they do not consider them homes as Westerners do. Houses provide only shelter and a place to store goods, eat and sleep. Days are spent primarily outside, tending extensive herds of alpacas, llamas and sheep, which supply them with fibers for weaving, dung for fuel and a regular source of food. In Pacchanta, the Quechua still follow the organizing principles established for harsh high altitudes by their Inca ancestors such as ayni (reciprocity), mita (labor tribute), ayllu (extending social networks) and making pagos (offerings to the mountain gods).

The grandfather of Maria’s children, Mariano Turpo, moved here in the 1980s during the reorganization of the Spanish colonial agricultural system, when the Hacienda Lauramarka was dismantled after a national agrarian reform that began in 1969. Villagers knew him as a respected altomisyoq, or the highest level of Andean ritualist, one who could converse directly with the mountain spirits on behalf of the people.

Maria, like Mariano, is well known in the region, as one of Pacchanta’s finest weavers. Knowledge of motifs and the skill to weave fine cloth increases not only a woman’s status but also her ability to provide for her family. Trekkers ending their hikes around Ausangate at Pacchanta’s bubbling hot springs like to buy these beautiful textiles.

**********

While learning to write in rural schools is a valued accomplishment, weaving is the community’s favored form of expression. Speaking in a strong voice with her eyes fixed on the threads that must stay taut, Maria says that writing is “sasa,” which means “difficult” in her native language of Quechua and that of her Inca ancestors. She learned her expert skills and vocabulary of designs from her mother, Manuela, and her aunts, who in turn had learned from their own mothers and aunts.

For Quechua people, the act of weaving is both social and communal. The entire extended family gathers outside as the looms are unrolled, the weavings uncovered and work begins. For many hours during the dry season, the family members weave, joke and talk while also keeping an eye on children and animals. Maria’s granddaughter, Sandy, and the younger nieces started out working on toe looms making belts and later bags without designs. They eventually graduate to more intricate and larger textiles, mastering the difficult task of leaning back with exactly the right tension to create straight rows and even edges.

In Pacchanta, as is traditional throughout the Andes, Maria taught her daughter Silea the designs in a particular sequence, as Manuela had taught her. The designs, or pallay (Quechua for “to pick”), help people remember their ancestral stories, as they are constructed one thread at a time. The younger girls often count aloud the pick-up patterns in Quechua numbers, hoq (1), iskay (2), kinsa (3), tawa (4) and so on, as they memorize the mathematical relationships of the pattern. So Maria and her sister Valentina taught Silea and the other girls how to prepare the warp by precisely counting each yarn so the pallay could be carefully lifted with her wichuna, before passing the weft thread to securely join the loose yarns into a textile. An entire visual nomenclature exists solely for colors, sizes and shapes of glacial lakes, such as Uturungoqocha and Alkaqocha, which serve Pacchanta as natural reservoirs.

**********

Weaving of fine textiles remains the province of women. Many aspects of life in Pacchanta are defined by gender, especially during planting season, which begins on the day after the September full moon. All the villagers understand about coordinating planting with the phase of the moon in the late dry season, just as their Inca ancestors did, as described in the Spanish chronicles by Garcilaso de la Vega in 1609. Maria’s sons, Eloy and Eusavio, and their uncles till the earth with traditional chakitajllas, Andean foot plows, while Maria and the other women follow, inserting seeds and a fertilizer of llama dung. For Quechua, during planting time the fertility of pachamama (Mother Earth) is strengthened by the balance of men and women working together to encourage good crops.

Still, men are involved with some aspects of textiles. Eloy, for instance, knits chullos, or Andean ear-flapped hats. It is a man’s duty to make his son’s first chullo so if a man cannot knit one, he must barter with another man. Men also make ropes and weave the coarser bayeta sheep’s wool cloth for pants and polleras skirts. While Eloy and Eusavio understand many Quechua names for Pacchanta weaving designs, they defer to the older women, as other men do, if disagreements arise about designs. Women are considered the final authority on their community’s design repertoire, as they relate to Quechua mythology and are responsible for instructing the next generation.

Quechua hands rarely stop moving. Whenever Silea walked to the nearby village of Upis, bearing loads inside the woven carrying cloths called kaypinas, her hands constantly spun yarn from fleece on a drop spindle wooden staff about a foot long with a weighted whorl. Manuela, even in her late 80s, was the finest spinner of all, but every family member spins alpaca and sheep fibers into yarn using a puska, or pushka, a name derived from the spinning motion of the spindle.

At Maria’s house, three generations of women stay busy cooking, feeding the guinea pigs, embroidering details on cloth, throwing pebbles at the herd, or whirling a sling to make a noise to move the animals. Guinea pigs are Quechua garbage disposals, not pets, and an Andean culinary delicacy. When Maria sponsors a wedding, festival, or baptism, the fattest ones are roasted and seasoned with huatanay, (Peruvian Black Mint), a cross between basil, tarragon, mint and lime. Rituals mark passages in Quechua lives, such as the first haircut: in highland communities, a rite as important as baptism.

In the late afternoon, family members eat a hearty evening meal of chayro (a nutritious soup supplemented by vegetables from markets down the valley), boiled potatoes and a steamy maté of coca or another local mint known as munay. The evening fires are ignited against the cold by blowing into a long tube or piece of bamboo on the embers of the smoldering dung coals. Quechua value a strong work ethic, a virtue that stretches back to the Inca. They rise with the sun and go to sleep when night falls.

Depending on remaining sunlight and warmth, Maria and Manuela sometimes go back outside to weave or embroider until the light disappears, often accompanied by Silea. On one such occasion a few years back, Manuela looked over a poncho that her granddaughter had woven and said, “Allin warmi,” which means “You are a good Quechua woman because you have become an accomplished weaver.”

When Manuela died of old age several years ago, Maria became the family matriarch. Since then, tragedy has hit the family. A lightning bolt struck 25-year-old Silea as she walked to Upis, as she had done for years. When death comes, Quechua people wrap their loved ones for burial in their finest cloth, the culmination of a life of connection with textiles. From an infant’s first breath to her last, beautiful textiles provide not only warmth, love and consolation but also a tangible sacred knowledge that they connect to a strong tradition of proud people stretching back centuries.

Today, outside the village of Pacchanta, when Maria unrolls her loom and begins weaving, she conveys to her daughters-in-law, granddaughters and nieces a sense of Quechua identity through the intricate designs of their ancestors. The majestic sacred mountain looks on just as it has for centuries past.

Related Reads

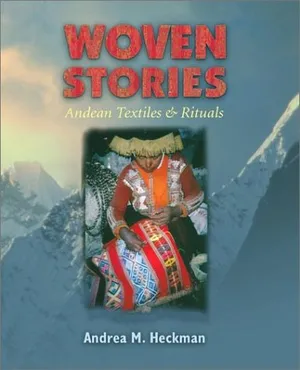

Woven Stories: Andean Textiles and Rituals

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.