Welcome to the Tundra: Kobuk Valley, One of America’s Least-Visited National Parks

Dramatic weather and impassable terrain shouldn’t stop you from visiting this park

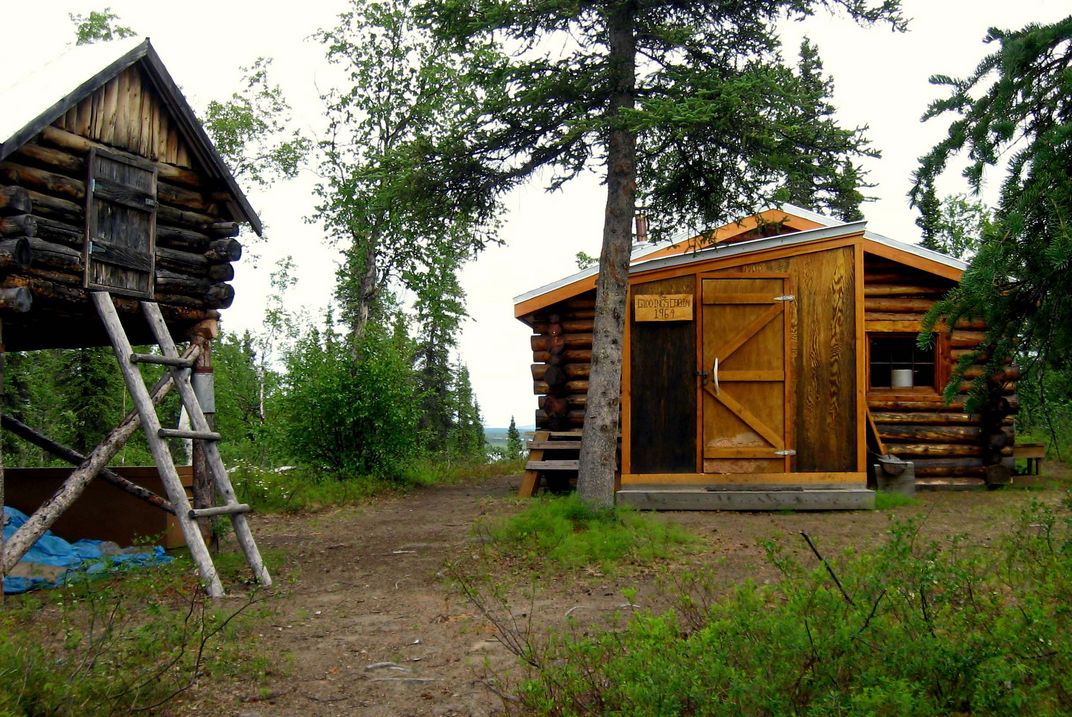

There are no roads, no trails, no facilities, and no rangers at Alaska’s Kobuk Valley National Park, one of the least-visited national parks in America. (It is so difficult to get there, the National Park Service doesn’t officially track visitor numbers). Located about 30 miles north of the Arctic Circle, the terrain is almost impassable, temperatures vary wildly, the landscape is vast and it can seem as if the sun doesn’t set in the winter. It’s also dangerously remote—basically only accessible by plane, and unpredictable storms can make air travel a hazardous affair.

“[Kobuk Valley National Park] is the way the heck out there. It’s in the middle of the wilderness,” says Linda Jeschke, chief of interpretation and a ranger with the Alaskan Region of the National Parks Service. Needless to say, a resort vacation at Disney World this is not. But for adventurers, explorers and tundra enthusiasts, Kobuk Valley is not to be missed.

Spread out over 1.7 million square miles, Kobuk Valley’s natural features include flowering sand dunes, frozen mountains, mushy lowland tundra, a sweeping river and polygon-shaped permafrost patterns. Then there are the Western Arctic caribou—nearly half a million of them traversing the tundra twice a year, moving north in the spring and coming back south in the fall. “If you are flying above the park, you can see their trails in the tundra. At first glance, you may ask yourself ‘are those bicycle tracks?’ but no, it’s the caribou who have been going back and forth for thousands of years,” says Jeschke. Other fauna in the region include wolves, red foxes, raptors, salmon (swimming in the Kobuk River, 60 miles of which run through the park) and bears. Grizzly and black bear tracks are all over the sand dunes, representing their presence in the park.

Kobuk Valley is defined by its remoteness. The closest town with significant services is the 3,000-person community of Kotzebue, 100 miles to the west. The only way to get into the park is by plane (the National Parks Service provides a list of contracted and permitted commercial air taxis on their website). Pilots drop off visitors at a location of their choosing— “Basically, you put your finger on the map ... they'll tell how close they can get you to that spot,” says Jeschke—and return at a prearranged day and time. That is, if the weather cooperates. Fogbanks in Kotzebue can prevent air taxis from taking off and, with little in the way of communication options, visitors can get stranded for days. “You could be hanging out on the sand dunes, wondering if you have been forgotten. You better have enough food, patience, and hope you brought a big book,” says Jeschke.

In fact, one of the biggest dangers of visiting the park is that there’s no prompt way of getting help if something were to happen. Your adventure into Kobuk Valley needs to be mistake-free. As Jeschke puts it, "Nobody is going to help you ... so, if you twist your ankle or a bear tears into your tent, which could all happen, help is a long ways away.”

But while the region is very remote, it is inhabited. In fact, local populations have lived here for thousands of years. The Inupiat are hunters—bears and caribou are their usual targets—who live around the Kobuk River in villages of several hundred people. The tundra is their home, and living in these extreme conditions is a part of their history and identity. For them, criss-crossing this landscape, most often on snowmobiles, is a way of life.

For the rest of us, being an experienced hiker and camper is a prerequisite for visiting Kobuk Valley. But if you’re up to the challenge, the place offers a once-in-a-lifetime adventure. In August and September, the tundra changes to orange and red, the weather is mild and thousands of caribou traverse the dunes. The winter season, meanwhile, offers the opportunity to see the Alaskan sun at its finest. “It doesn't seem logical, but there is not a time here when the sun goes below [the] horizon and stays down all winter long. You know how you stick a pencil in a glass of water and it looks bent? That's what is going on here with the atmosphere,” says Jeschke. (Look at the fourth diagram on this page for a visual representation of this phenomenon.)

Of the 59 national parks in the United States—all celebrating National Parks Week this week—none are as remote and physically demanding as Kobuk Valley. But as the pictures above prove, its spectacular beauty makes it worth the trek.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.