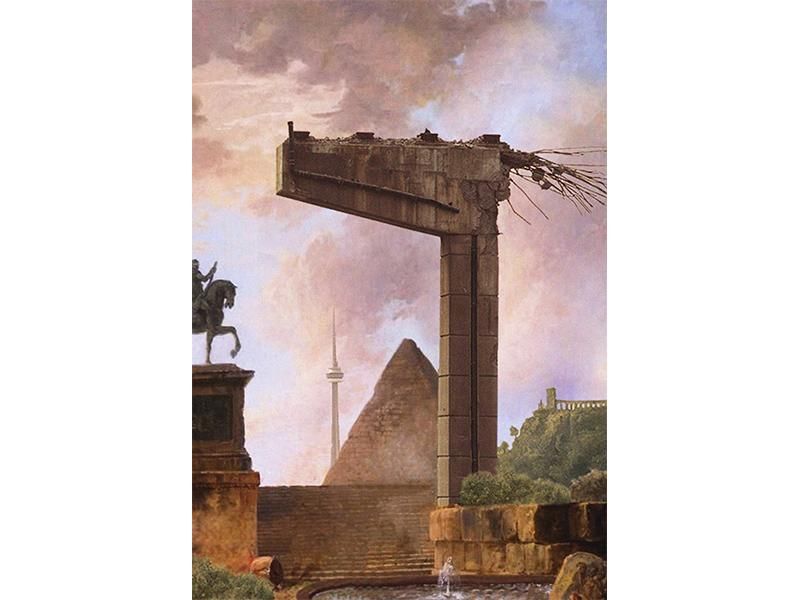

What Should a Contemporary Monument Look Like?

A new multi-city art exhibition called “New Monuments for New Cities” tackles this question head on

What makes someone or something worthy of having a monument in their honor? That question has been the subject of much debate in recent years, and has resulted in the razing of dozens of Confederate monuments scattered across the United States in response to a public outcry for their removal. Now, looking ahead, communities are faced with a new question: What monuments, if any, should replace them?

Inspired by this ongoing dialogue, the nonprofit organization Friends of the High Line launched a collaborative public art exhibition this week at Buffalo Bayou, a waterway flowing through Houston. Called “New Monuments for New Cities,” the yearlong initiative will travel to five different urban reuse projects throughout North America, with stops at Waller Creek in Austin, The 606 in Chicago and The Bentway in Toronto before ending at the High Line in New York City. The initiative’s purpose is to challenge local artists to “transform underutilized infrastructure into new urban landscapes” while also advancing the discussion of what a monument should be in the 21st century.

“We want to keep the conversation going about monuments and about what we want to see celebrated in our squares and parks,” says Cecilia Alemani, director and chief curator of High Line Art. “Sometimes conversations can die, but I think it’s important to keep [this one] up. We’re also thinking about what is the importance of monuments in today’s contemporary art field. Can a monument take on a completely different shape or form? Can it be more text based? I think, especially now, sometimes when you walk into public spaces these monuments don't make sense to younger generations because they don’t know who these people are. So can [these monuments] be swapped with something that is more [recognizable] with today’s digital culture and pop culture?”

These questions are exactly what the Friends of the High Line posed to 25 artists—five artists in each of the five cities—who were chosen by a curatorial committee. The artists were challenged to create original pieces of artwork that could fill the void of empty pedestals and plinths dotting these cities’ public spaces.

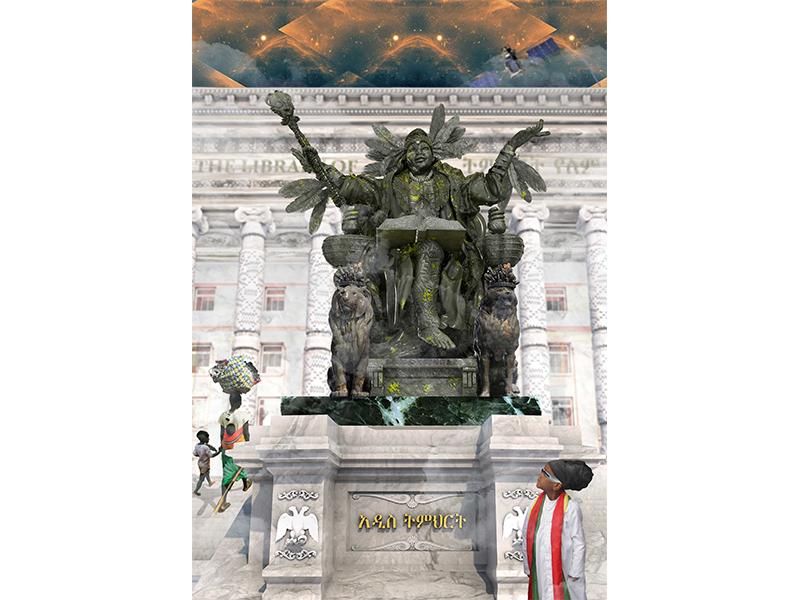

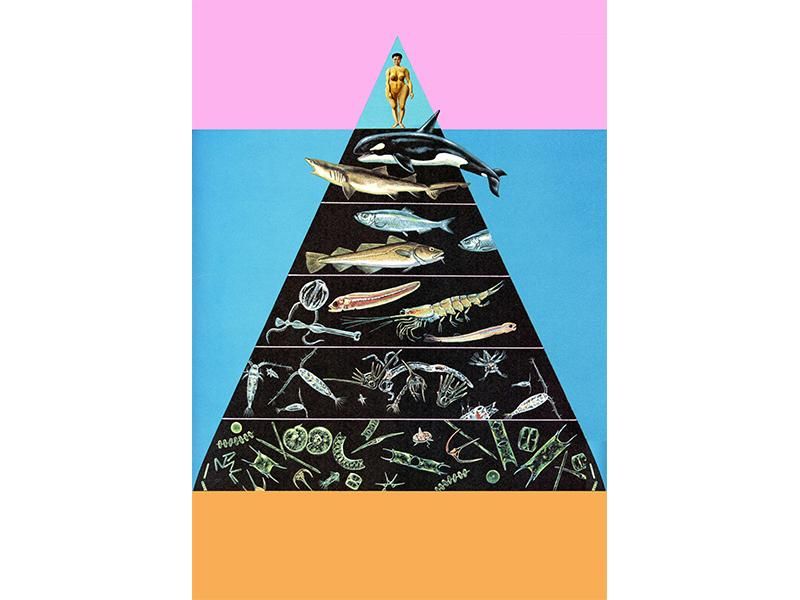

“We asked the artists who they wanted to see commemorated, which gave them the opportunity to answer this question in very different ways,” Alemani says. “Some of the artists created new monuments, while others reimagined existing ones.”

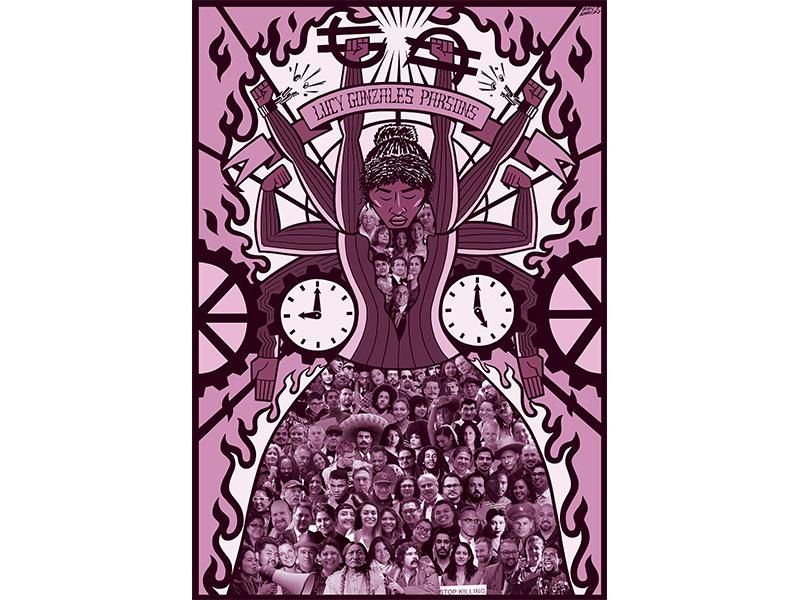

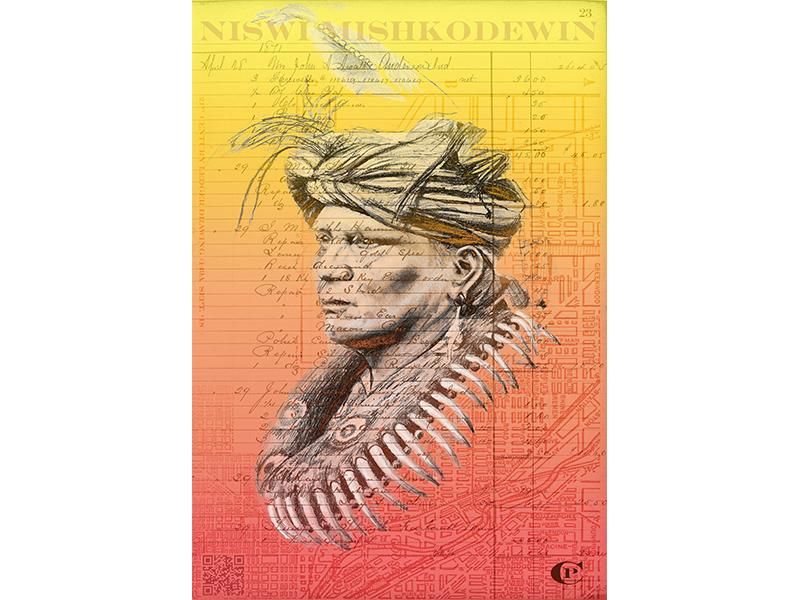

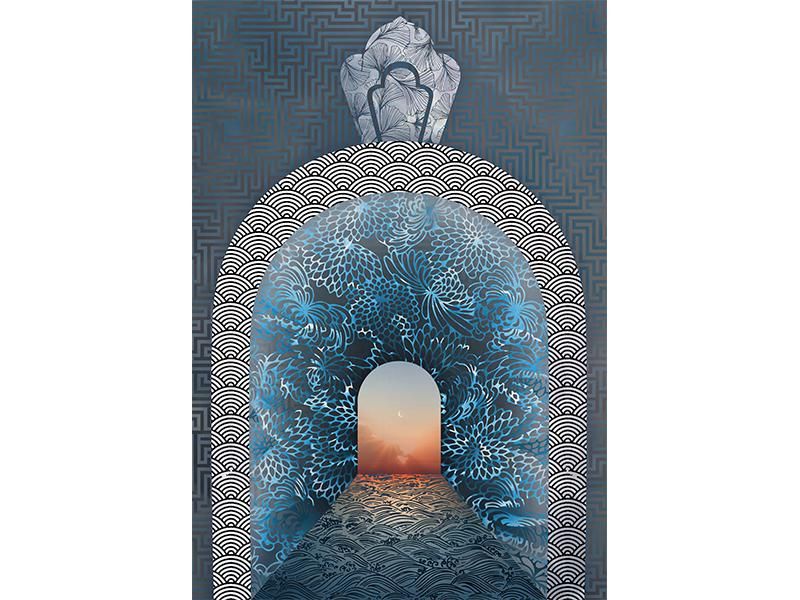

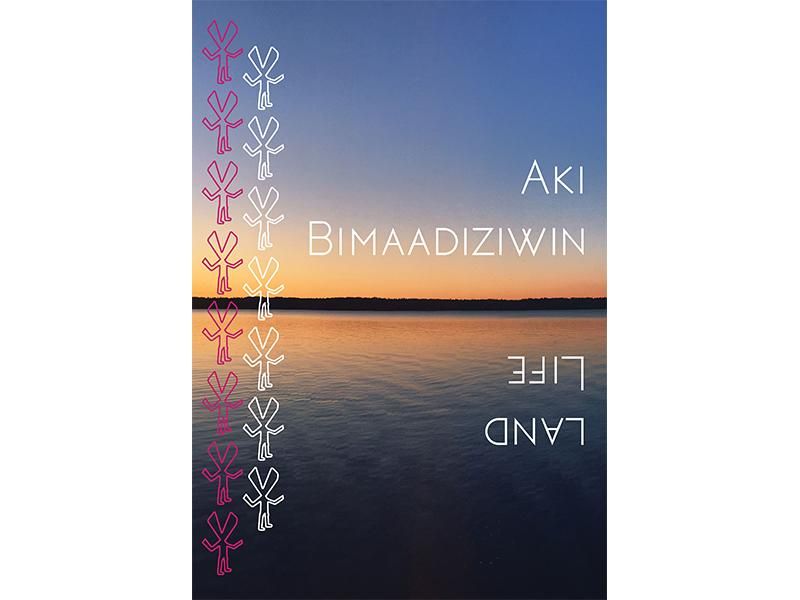

Artists didn’t have to look far for inspiration, with many of them taking a page from their own experiences or that of their communities. Susan Blight, an Anishinaabe interdisciplinary artist from Ontario's Couchiching First Nation, created a work employing a traditional Anishinaabe pictograph technique to honor her people’s connection to the land. Nicole Awai’s piece questions Christopher Columbus’ “discovery” of America while addressing the hot-button issue of whether or not a statue in his honor should be removed in New York City. (Earlier this year Mayor Bill de Blasio ultimately decided the monument would stay put).

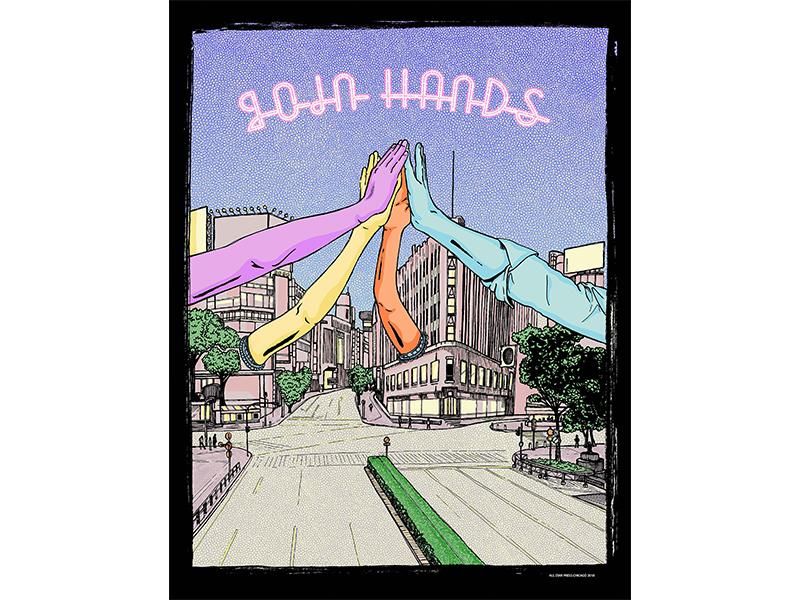

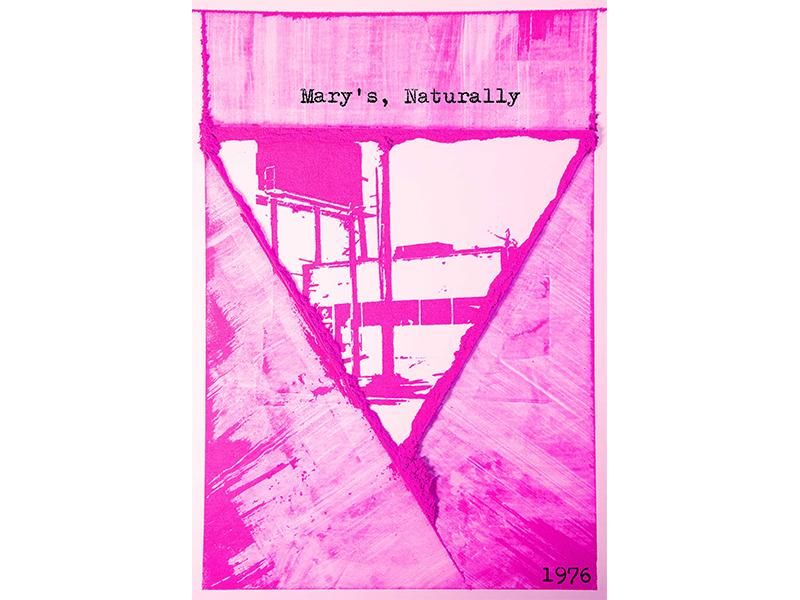

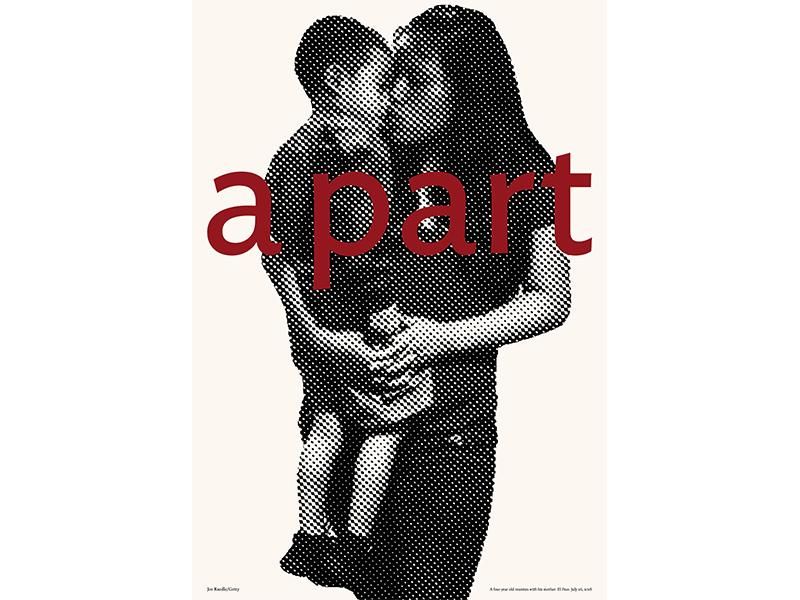

Other important topics addressed by artists include immigration, the LBGTQ community, capitalism, sexism and race.

“The entire exhibition taps into issues and concerns that validate figures who haven’t been highlighted in the past,” says Ana Traverso-Krejcarek, manager of the High Line Network, a group of infrastructure reuse projects across North America. “It’s a very diverse exhibition as a whole.”

The techniques employed by artists are also diverse, and include billboards, projections, flags, banners, hand-painted murals and vinyl wraps. Because it’s a traveling exhibit, each piece must easily be translated onto large-scale, wheat-pasted posters, which will go from site to site throughout the remainder of the year. In addition to the artworks on display, each site will host a variety of events, including artist talks, discussions with curators and more.

“We wanted to create something that is fun and engaging for communities,” Traverso-Krejcarek says. “But the exhibition is also important to monumentality and how different cities are grappling with the idea of who is immortalized and monumentalized and who isn’t.”

“New Monuments for New Cities” will be on display through October 2019.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.