When Rock Bands Flocked to Howard Finster’s Remote, Bizarre Artist Compound

Even today you can visit the site where groups such as R.E.M. found a true artistic genius

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/55/53/5553d113-22ba-4a1b-a004-80b7a6ac6ea7/x-welcome-sign.jpg)

Most art critics never took Howard Finster seriously. If they wrote about him at all, they shunted him off into the category of “self-taught folk artist” or “outsider artist,” a quaint curiosity but nothing to take seriously. Even when his paintings were shown at the Library of Congress or the Venice Biennale, they were presented as novelty items.

But rock musicians, including the legendary ’80s band R.E.M., recognized Finster as one of their own: an unschooled genius who shrugged off the establishment's condescension to enjoy the last laugh.

After R.E.M. filmed its first music video at the fellow Georgian’s home studio in 1983, Finster and lead singer Michael Stipe then collaborated on the cover for the group’s 1984 album, Reckoning. The New York band the Talking Heads commissioned Finster to paint the cover for their 1985 album, Little Creatures; it was named “Album Cover of the Year” by Rolling Stone. Another Georgia musician, the Vigilantes of Love's Bill Mallonnee, wrote a song about Finster: “The Glory and the Dream.”

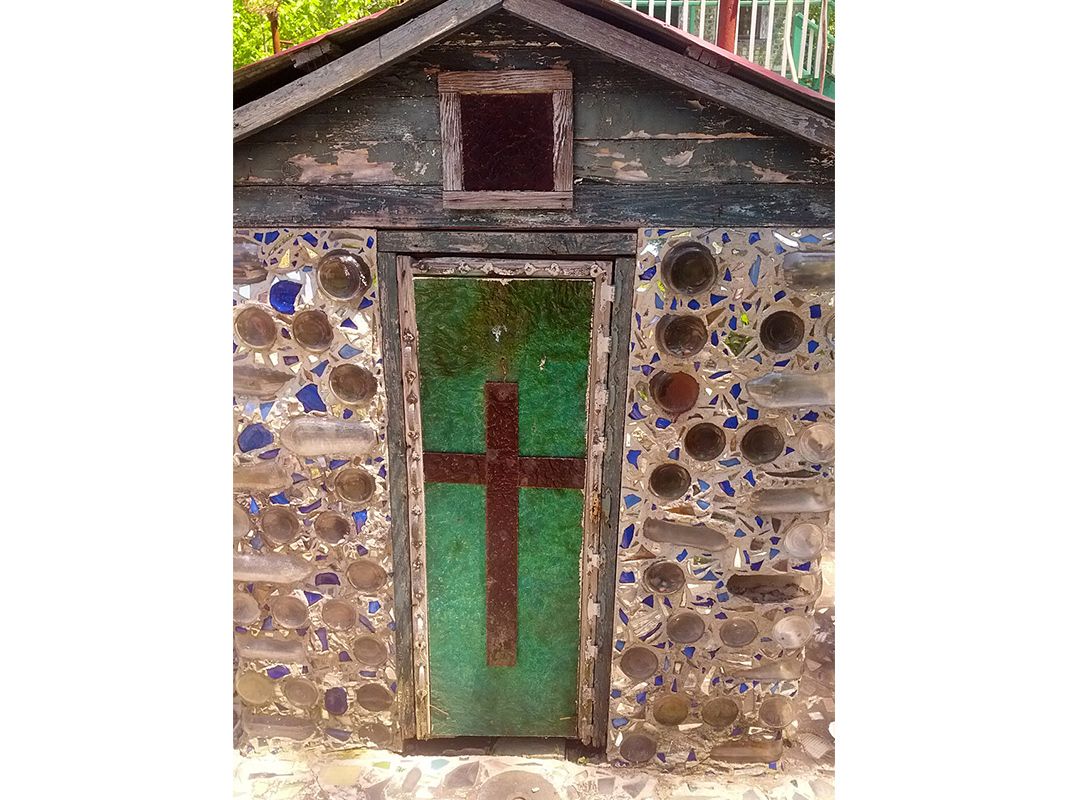

Finster’s studio, known as “Paradise Garden,” is still standing on the land he bought in 1961, located at the end of a narrow street in the unincorporated town of Pennville, Georgia. The bicycle repair shop that provided his main income for years lives on, as do many of the buildings Finster built as parts of his “sacred art” project: the Mirror House, Bottle House, Mosaic Garden, Rolling Chair Gallery, Hubcap Tower and the five-story World's Folk Art Chapel.

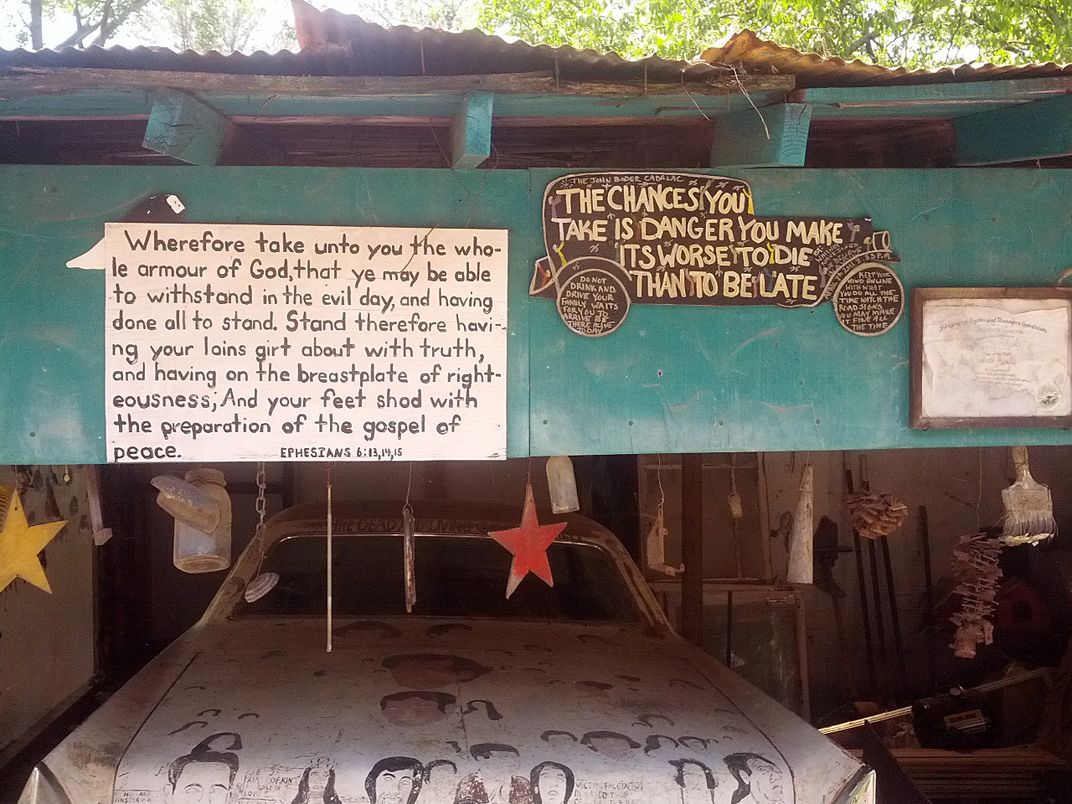

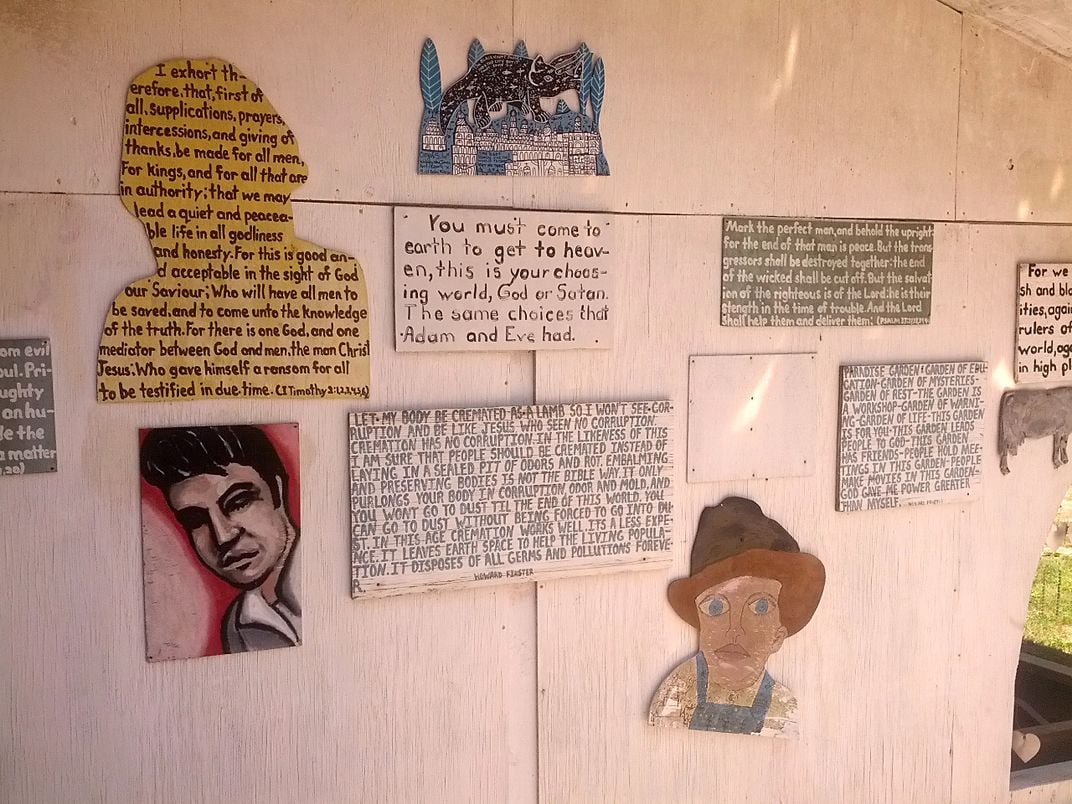

During the 1980s and ‘90s, it was not unusual to a big tour bus to pull up at Paradise Garden and for a rock band to climb out and marvel at Finster’s exuberant, unruly visions. The exteriors and interiors of his buildings were covered with Biblical verses, floating angels, Satanic flames and celestial clouds, all part of the painter's mission to spread God's word

But as the painter aged, he moved away in 1994 and finally died in 2001. In his absence, the compound declined dramatically: the detachable art works were removed by family members and looters; the buildings leaked, tilted and sank into accumulating mud. It wasn’t until 2012 when Chattooga County bought the property and turned it over to the non-profit Paradise Garden Foundation that the property began to turn around. Heading up the foundation is 32-year-old Jordan Poole, who grew up in the area before earning a master's degree in historic preservation from Savannah College.

“My grandparents had a grocery store two blocks away,” Poole remembers. “My mother went to grade school at the top of the hill, and my family's buried a block away. I first visited here when I was five years old, and to me it was magical, enchanting. But my dad would say, ‘There’s that crazy Finster place.’ That was the common attitude. He was that crazy Baptist preacher who did what you shouldn’t do.”

When I visited in May, Poole provided a personal tour. He pulled out a mini-album of snapshots to show how bad the property had become by 2010. Water is always the biggest enemy of abandoned buildings, and rain had streaked the walls and ceilings, rotted the beams and carried the mud into every low-lying area. When I glanced from the photos to the landscape in front of me, the transformation was remarkable.

Finster’s former studio, a clapboard bungalow painted with images of George Washington, an orange panther and willowy saints, now serves as a gift shop and visitors’ center, where you can buy a ticket for the low price of $5 (even cheaper if you’re a senior, student or child). As you walk out the back door, you’re confronted by the World's Folk Art Chapel, which resembles nothing so much as a five-layer wedding cake, featuring a 12-sided white-wood balcony, a cylindrical tower and an inverted-funnel spire.

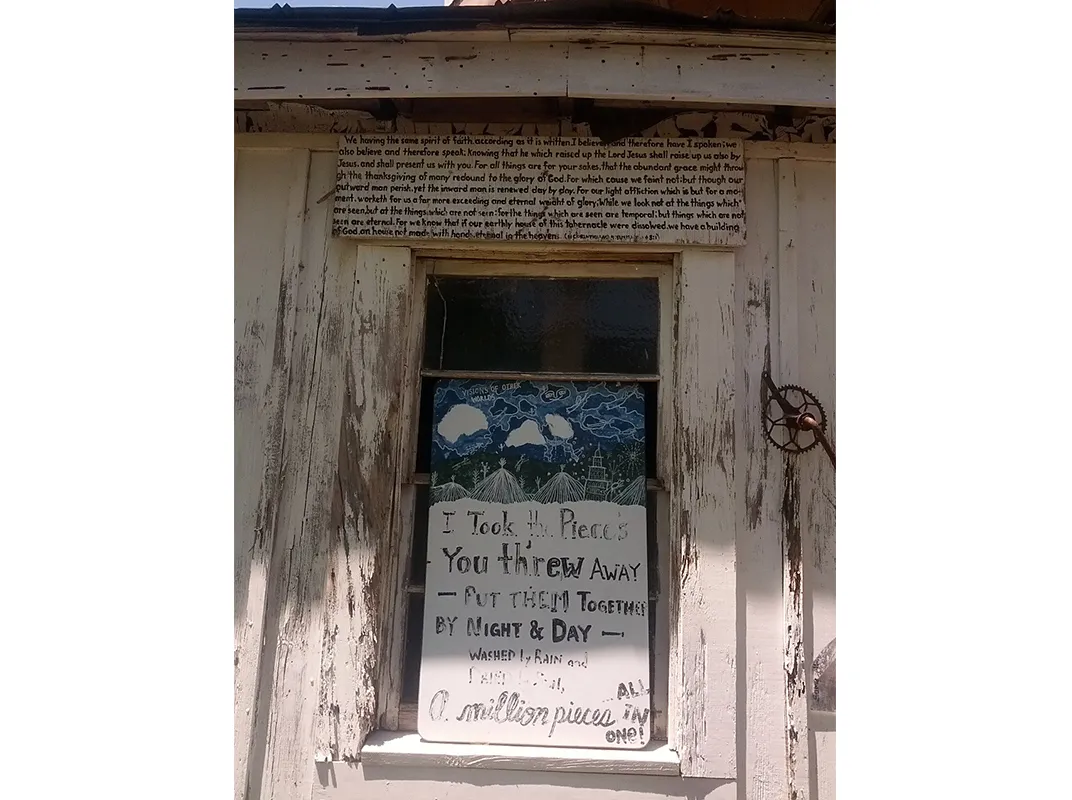

Covering one of the chapel's windows is a painting that serves as the most succinct summary of Finster’s artistic purpose: “Visions of Other Worlds,” it reads across a landscape of exploding volcanoes and swirling stars. “I took the pieces you threw away—put them together by night & day—washed by rain and dried by sun—a million pieces all in one.”

Indeed recycled materials are to be seen everywhere: rusted farm implements, teapots, broken dishes, light fixtures, empty pop bottles, plastic toys, sea shells, shattered mirrors, bicycle rims and much more, all juxtaposed with wire and cement into new arrangements—always startling and often beautiful. A workshop is still filled with such bits and pieces waiting to be assembled into new art works.

Finster dug serpentine paths for the creek that crossed his property so the water snaked between his structures large and small. It was his own, personal “Garden of Eden,” as he put it. The creek had been silted up, but it was one of the first things restored by the new foundation.

One shed is raised on stilts and covered inside and out with mirrors. When you walk into this “Mirror House,” you find your reflection fractured and multiplied many times over. A 20-foot-tall tower of hubcaps is entangled in vines. His hand-painted Cadillac is parked in another shed. Three adjacent trees that he braided into one are still standing. The Rolling Chair Ramp Gallery, designed for wheelchairs, is a long, L-shaped building lined with news reports and testimonials as well as art works by Finster and his colleagues, all annotated by Finster’s black Sharpie.

Outsider folk artists have a reputation for being isolated loners, but Paradise Garden deflates that stereotype. Even as a septuagenarian Baptist minister, Finster loved to have scruffy rock'n'rollers and camera-clicking tourists visit, and their greetings are hung in the gallery. He especially like to meet his fellow outsider artists, and such famous names as Purvis Young, Keith Haring and R.A. Miller all left art works behind in gratitude for Finster’s trail-blazing example.

Finster’s legacy is complicated by the fact that he was more interested in getting his message out to as many people as possible than in creating the best possible art. Later in his career, he started churning out what he called “souvenir art,” multiple variations on a few simple themes to feed the demand. These were inevitably lacking in inspiration and diminished his reputation, but his best work stands up as great American art. He had a strong sense of line and color and a genius for combining text and imagery. But the greatest of his works may be Paradise Garden itself.

The Paradise Garden Foundation has accomplished much in a few years, but there is still much to do. The buildings were originally covered with paintings on plywood, and the foundation wants to restore those—not with originals that will be damaged by the elements but by weatherproof replicas. The most expensive challenge is stabilizing and weatherproofing the World's Folk Art Chapel. Paradise Garden deserved its notoriety in the ‘00s as a dilapidated ruin of its former self, but it deserves that reputation no longer.

The site is worth an out-of-the-way trip not only for art lovers but also for music fans—not just because Finster painted a few album covers but more so because he seemed to embody the unschooled, non-corporate, non-academic spirit of the earliest, strangest and best rock 'n' roll.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/geoff-vancouver-bio-lightened.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/geoff-vancouver-bio-lightened.jpg)