When Tuberculosis Patients Quarantined Inside Kentucky’s Mammoth Cave

In the early 1840s, believing the air was therapeutic, Kentucky doctor John Croghan ran a consumption sanatorium deep underground

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/5f/0c/5f0c422f-a063-410e-a39d-78597f15c0fe/tb_hut_mammoth_cave_2.jpg)

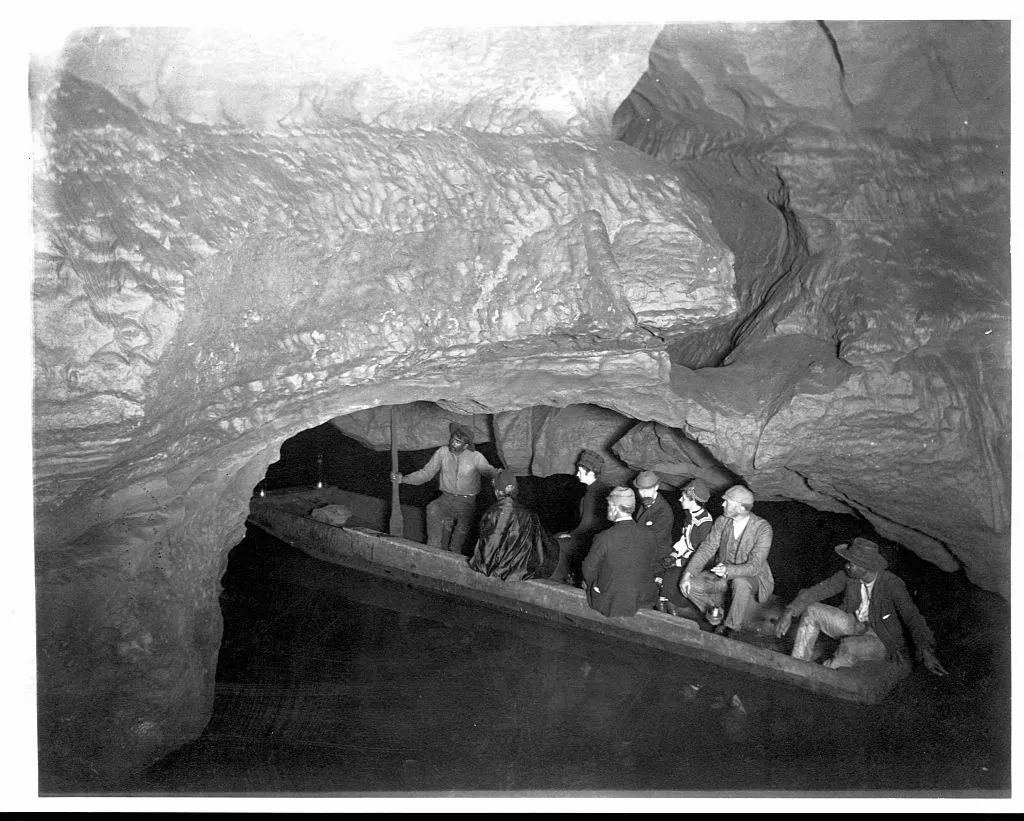

During the latter half of 1842, pale figures walked the shadows of Mammoth Cave, the world’s longest-known cave system, near central Kentucky—hospital gowns clung to their withering frames. The ghastly figures appeared as phantoms, but these were living, breathing people, though barely—their lungs had been ravaged by pulmonary consumption, later known as tuberculosis. Desperate for a cure, the patients had retreated to the underbelly of the Earth, one mile into Mammoth Cave, a place pitch black to the naked eye.

“I used to stand on that rock and blow the horn to call them to dinner,” recalled a slave and Mammoth Cave guide named Alfred. “There were fifteen of them and they looked more like a company of skeletons than anything else.”

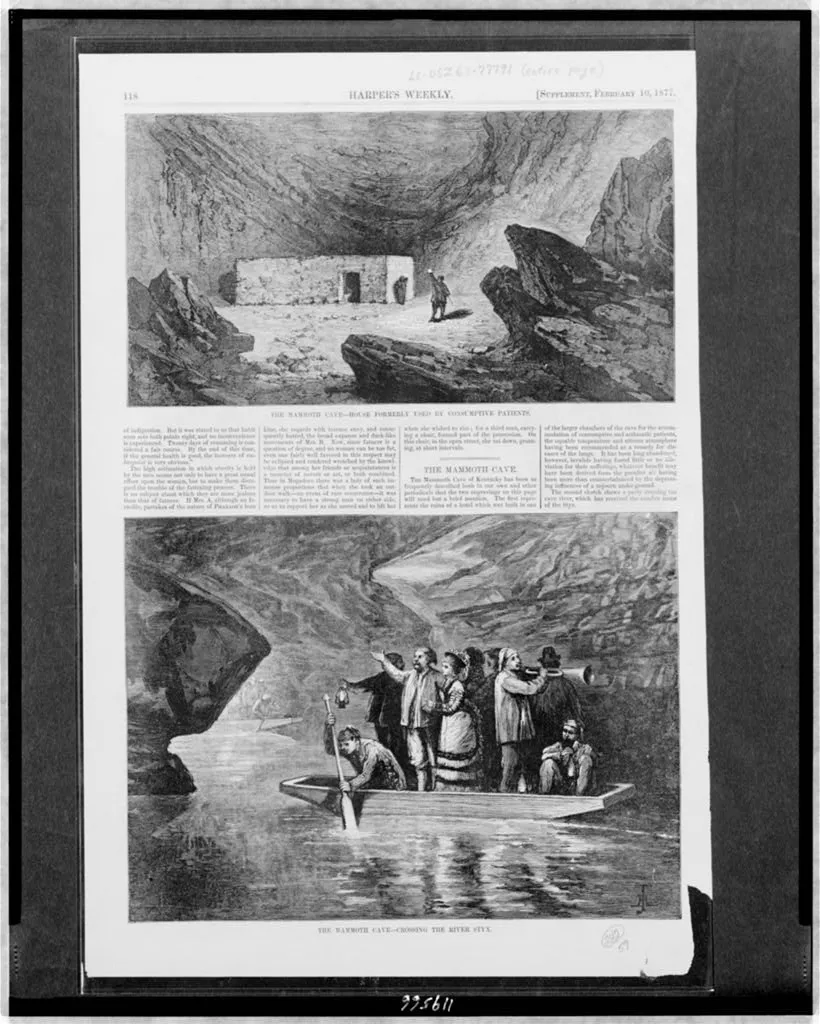

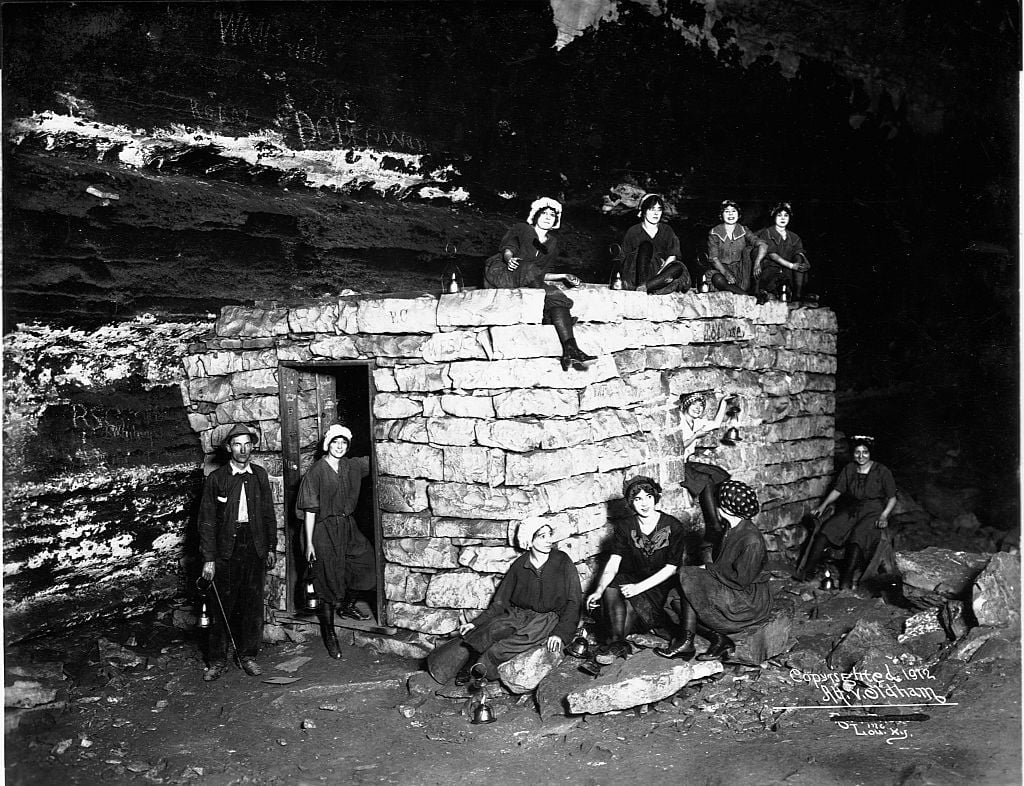

Three years earlier, in 1839, John Croghan, a Louisville, Kentucky, doctor, slave owner and nephew of George Rogers Clark, had purchased Mammoth Cave, a popular tourist attraction first discovered by Europeans around 1790, for $10,000 (roughly $290,000 in 2021). Believing the cave’s air possessed curative qualities, Croghan ordered his slaves to construct a consumption sanatorium consisting of two stone cabins and eight wooden huts—each measuring 12-by-18 feet, built upon a tongue-and-groove floor and capped by a canvas roof. Patients, many of them wealthy, some who had traveled long distances, synced their watches to the outside world to maintain a semblance of time; they lined the sanatorium with fresh foliage to bring life to the barren landscape, and prayed for relief.

“Croghan had studied in Pennsylvania as an apprentice to Dr. Benjamin Rush, one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence,” says Jackie Wheet, a Mammoth Cave National Park Ranger. “He heard that people working in Mammoth Cave were known for their good health, so he experimented. He let some of his patients live in the cave, breathing the cool, pure cave air to see if it helped them feel better—they actually paid the doctor quite a bit of money for the treatment.”

Between the end of 1842 and beginning of 1843, somewhere between 16 and 20 consumption patients filed into the dark recesses of Mammoth Cave—where humidity fluctuates, but timber doesn’t rot and dead animals never decay. Perhaps the cave’s air might not only preserve, but restore, thought Croghan.

“We think there might have been a few other patients that went unaccounted for,” says Wheet.

***

In the mid-19th century, before a vaccine was developed in 1921, toxic substances like hemlock and turpentine were offered as remedies for consumption. So were bleedings, purgings, cod liver oil and vinegar massages—making Croghan’s proposition of an underground sanitorium one in a long line of attempted remedies. In fact, Croghan’s first consumption patient, William Mitchell, a local Kentucky physician himself, endorsed the medical experiment, entering the cave in the late spring of 1842.

“About the 1st of December last, I was taken with a slight cough,” wrote Mitchell in the November 10, 1842, edition of Louisville, Kentucky’s Courier-Journal. “I expectorated a great quantity of pus … had difficulty breathing, and was very weak and feeble. After trying a number of popular remedies for my disease, without receiving any benefit, I concluded to try the effects of a residence in the Mammoth cave. I went in the cave on the 20th of May, and took up my residence about three-fourths of a mile from the entrance. For some few days I felt worse in every particular, though in the course of a week I became much better. I could breath [sic] with the greatest of ease.”

Christian McMillen is a historian and associate dean at the University of Virginia and the author of Discovering Tuberculosis. “It was a relatively common notion that air—whether it's altitude, winter air, desert air, or what have you—was a good solution for tuberculosis,” he says. “Sometimes it did help. But there was a kind of mistake in correlation with causation. TB is contagious, so in this case, my guess is that you take five people with TB, and five people without TB, and put them together in a cave, and you’re going to wind up with 10 people who have TB.”

With patients like Mitchell reporting improved conditions, Croghan drew up plans for an even larger hotel sanatorium inside Mammoth Cave.

“Tuberculosis is a chronic lung infection caused by mycobacterium tuberculosis, a bacteria that spreads in the air from person to person,” says Bradley Wertheim, a pulmonologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and instructor at Harvard Medical School. “The only thing that's going to make these patients better definitively, is to kill the mycobacterium with the proper chemotherapeutic agent. However, from a psychosocial point of view, if you just take a bunch of sick patients and provide for them, if they have fellow patients they can commiserate with, you could see how some might initially feel a little better. But from a medical standpoint, will that treat that tuberculosis? No.”

Mitchell’s positive report was wired across the country, though not everyone believed his account, including fellow doctors. “I was also informed by various persons who reside there, that no person, to their knowledge, had received any permanent benefit from the Cave,” wrote Omri Willey, an Ohio doctor, in the December 29, 1842, edition of the Boston Post. “The benefit which Dr. Mitchell is supposed to have received from it, and which probably induced him to publish his communication, was only temporary—that he was then fast declining, and could not be induced to return to the Cave, notwithstanding it possessed such powerful sanative properties.”

***

During the winter of 1842 and 1843, as fires and lard oil lanterns constantly burned, illuminating the pitch dark, meals were prepared or brought in from outside. But smoke and ash from the fires and lanterns, combined with the cave’s cold, dank air and lack of sunlight, slowly transformed Croghan’s sanatorium into a living hell.

“I left the cave yesterday under an impression that I would be better out than in as my lungs were constantly irritated with smoke and my nose offended by a disagreeable effluvia, the necessary consequence of its being so tenated [sic] without ventilation,” wrote Oliver Hazard Perry Anderson, one of Croghan’s patients, in a January 12, 1843, diary entry. “The thermometer stood at 40 degrees in the shade when I came out, and I cannot tell you how delightful the upper world was to all my senses. The air was sweet, pure and agreeable and the light to my surprise did not hurt my eyes.”

While Croghan was housing his consumption patients, he continued to operate Mammoth Cave as a tourist destination. When visitors happened upon the ghostly, skeleton-like patients, when they heard them hacking up blood in the distance, they were terrified.

“The idea of a company of lank, cadaverous invalids wandering about in the awful gloom and silence, broken only by their hollow coughs—doubly hollow and sepulchral there—is terrible,” wrote Bayard Taylor, a mid-19th-century visitor to Mammoth Cave, in At Home and Abroad: A Sketch-book of Life, Scenery and Men.

Croghan’s experiment was terrible. “The sixteen or so patients started trickling in over the course of five to six months—from 1842 until the beginning of 1843,” says Wheet. “Many of them started complaining about how cold they were. The longest anyone stayed was about four and a half months, and nearly every one of them died within days or weeks of exiting the cave.”

Twenty-five years later, in its December 1867 edition, The Atlantic Monthly wrote, “Like plants shut out from the generous, fostering sun, they paled and died. The appearance of those who came out after two or three months’ residence in the cave is described as frightful. ‘Their faces,’ says one who saw them, ‘were entirely bloodless, eyes sunken, and pupils dilated to such a degree that the iris ceased to be visible; so that, no matter what the original color of the eye might have been, it appeared entirely black.’”

***

By the time Croghan ended his medical experiment in early 1843, multiple people were dead, including Charles Marshall, a New York reverend whose wife stayed by his side until the end. At least five patients never exited Mammoth Cave alive—the withering foliage alongside the limestone sanatorium offered a fitting symbol for Croghan’s failed exercise. Oliver Hazard Perry Anderson was one of the few who survived.

“I would not have left the cave had I calculated on anything but better weather,” wrote Anderson in January 1843, “but 'tis over now and I shall try to be as careful of consequences as I can be, I am sure I am better out than in if I take no heavy cold to settle on my lungs and I feel some considerable hope from the pleasant effect thus far that I will. No sense of chills annoy me and my strength is good. I don't look as well as when I entered the cave. Others will leave the cave soon, I think; two recently died. I am the 5th person who has left.”

Anderson died on May 17, 1845, of unknown causes. Croghan himself would succumb to consumption on January 11, 1849. Whether the doctor contracted the disease inside his sanatorium is unknown, but upon his death, his family tended to unresolved bills and lawsuits from his medical practice. Throughout 1849, the same Courier-Journal ad appeared at least eight times:

“NOTICE—All persons indebted to the estate of the late Dr. John Croghan are requested to make payment. Those having claims against said estate will present them to GEO. C. GWATHMEY, Executor”

In his will, Croghan left Mammoth Cave to his brother George and his nephews and nieces; his family owned the property until the 1920s. Two decades later, on September 18, 1946, Mammoth Cave National Park was dedicated, and in 1981, the natural wonder was designated a Unesco World Heritage Site.

Deep inside Mammoth Cave, past the quarter-acre-size Rotunda, where soldiers manufactured saltpeter gunpowder during the War of 1812; past The Church, where the local Methodist congregation gathered on sweltering summer days, their singing voices echoing like cherubim off cold cave walls; past Gothic Avenue, where weddings were once held beneath the Gothic-esque dripstone rock formations; past Giant’s Coffin, a colossal rock that appears like an oversized casket; and on about 100 yards, remain the vestiges of the two limestone huts that housed Croghan’s tuberculosis patients.

“When people see them, they usually ask, ‘Who lived here?’ ‘What were these for?,” says Wheet. “That’s when we tell them a doctor owned the cave in the early 1800s, and sick people lived here in hopes that breathing the cool cave air might help them feel better.”

Directly behind one of the huts stands Corpse Rock, a thick slab of rock where dead patients were purportedly laid out before being carried out by loved ones. Croghan’s consumption experiment had a weak foundation, but more than 175 years later, the doctor’s stone sanatorium still stands upon the firm floor of Mammoth Cave.

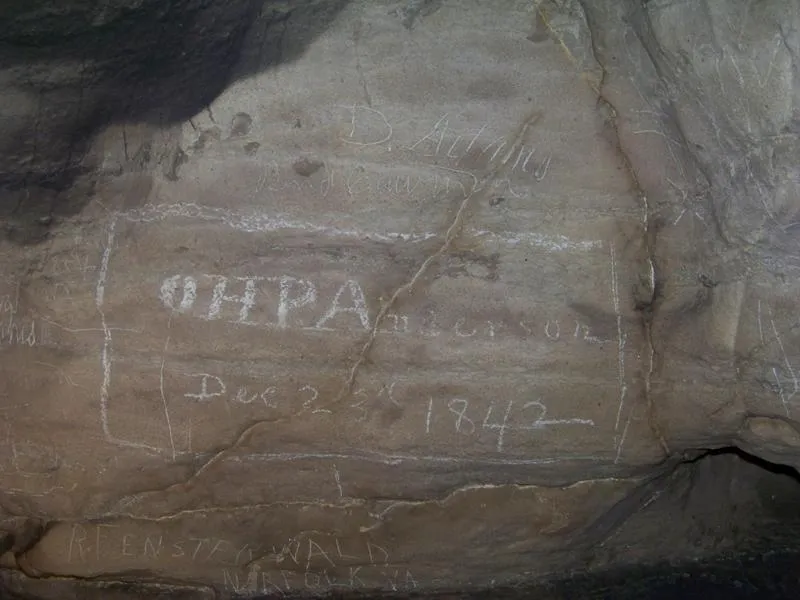

Just before Christmas Eve 1842, Oliver Hazard Perry Anderson took a rock and, with his ailing hands, etched his name upon a nearby wall, stone upon stone: “OHPAnderson Dec 23rd 1842.” Anderson remains immortalized deep inside Mammoth Cave, one of the only patients to escape John Croghan’s care alive.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.