Where Agatha Christie Dreamed Up Murder

The birthplace of Poirot and Marple welcomes visitors looking for clues to the best-selling novelist of all time

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Agatha-Christie-Greenway-estate-631.jpg)

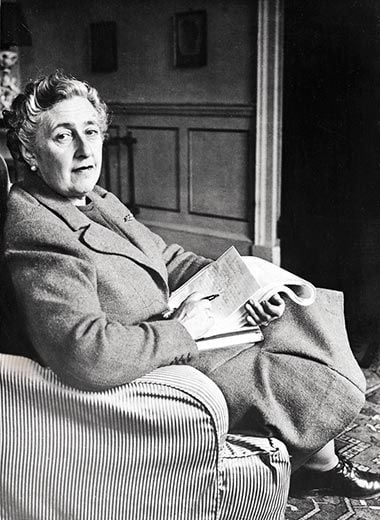

On a crisp winter morning in Devon, England, sunlight streams through the floor-to-ceiling French windows of the manor house called Greenway, the secluded estate where Agatha Christie spent nearly every summer from 1938 until her death in 1976—and which opened to the public in February 2009. Gazing beyond a verdant lawn through bare branches of magnolia and sweet-chestnut trees, I glimpse the River Dart, glinting silver as it courses past forested hills. Robyn Brown, the house’s manager, leads me into the library. Christie’s reading chair sits by the window; a butler’s tray holds bottles of spirits; and a frieze depicting World War II battle scenes—incongruous in this tranquil country retreat—embellishes the cream-colored walls. It was painted in 1944 by Lt. Marshall Lee, a U.S. Coast Guard war artist billeted here with dozens of troops after the British Admiralty requisitioned the house. “The Admiralty came back after the war and said, ‘Sorry about the frieze in the library. We’ll get rid of it,’” Brown tells me. “Agatha said, ‘No, it’s a piece of history. You can keep it, but please get rid of the [14] latrines.’”

Agatha Christie was 48 years old in 1938, gaining fame and fortune from her prolific output of short stories and novels, one series starring the dandified Belgian detective Hercule Poirot, another centered on the underestimated spinster-sleuth Jane Marple. Christie’s life had settled into a comfortable routine: part of the year was spent at her house in Wallingford, near Oxford, and part on excavations in the deserts of Iraq and Syria with her second husband, archaeologist Max Mallowan. But Christie longed for a vacation refuge. That summer, she heard of a handsome Georgian manor house, built around 1792, going up for sale; it was set on 33 acres, 15 miles from her birthplace, the village of Torquay. For Christie, Greenway—reachable only by boat or down a narrow country lane one and a half miles from the nearest village of Galmpton—represented, as she wrote in her autobiography, “the ideal house, a dream house.” The estate’s owner, financially strapped by the Great Depression, offered it for just £6,000—the equivalent of about $200,000 today. Christie snapped it up.

Here, the author and playwright could escape from her growing celebrity and enjoy the company of friends and family: her only child, Rosalind Hicks; son-in-law Anthony Hicks; and grandson Mathew Prichard, whose father, Rosalind’s first husband, Hubert Prichard, had been killed in the 1944 Allied invasion of France. Greenway served as the inspiration for several scenes in Christie’s murder mysteries, including the Poirot novels Five Little Pigs (1942) and Dead Man’s Folly (1956).

After Christie died, at age 85, the estate passed to Hicks and her husband. Shortly before their own deaths in 2004 and 2005, respectively, the couple donated the property to Britain’s National Trust, the foundation that grants protected status to historic houses, gardens and ancient monuments and opens the properties to the public.

Brown recalls several meetings with the frail but alert 85-year-old Rosalind, whose failing health required her to move around the house by mobility scooter. At one of them, Brown broached the subject of Greenway’s future. “The sticking point for Rosalind was that she didn’t want us to create a tacky enterprise—the ‘Agatha Christie Experience,’” Brown told me. Indeed, Hicks first demanded that the house be stripped bare before she would donate it. “If we show the rooms empty, the house will have no soul,” Brown recalled telling Rosalind. “If we bring things in from outside, it will be contrived.” Brown proposed that the house be left “as though you and Anthony just walked out the door.” Eventually, Rosalind agreed.

In 2009, after a two-year, $8.6 million renovation—“the house was in terrible shape,” says Brown—Greenway opened to the public. During the first eight-month season, it attracted 99,000 visitors, an average of 500 a day, nearly double expectations. Today, Greenway offers an opportunity to view the intimate world of a reclusive literary master, who rarely gave interviews and shunned public appearances. “She was hugely shy, and this was her place of solitude, comfort and quiet,” Brown says. Greenway “represents the informal, private side of Agatha Christie, and we have striven to retain that atmosphere.”

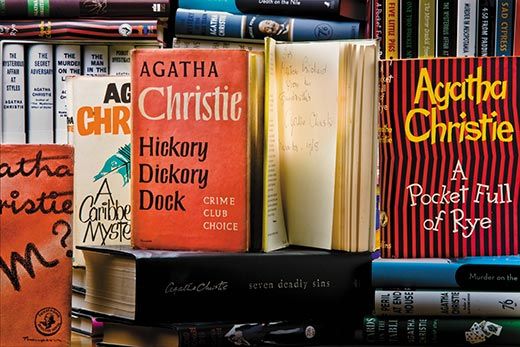

Greenway’s success is the latest, most visible sign of the extraordinary hold that Agatha Christie continues to exert nearly 35 years after her death. Her 80 detective novels and 18 short-story collections, plus the romances written under the pseudonym Mary Westmacott, have sold two billion copies in more than 50 languages—making her by far the most popular novelist of all time. Her books sell four million copies annually and earn millions of dollars a year for Agatha Christie Limited, a private company of which 36 percent is owned by Mathew Prichard and his three children, and for Chorion Limited, the media company that bought a majority stake in 1998. A stream of dramatized Poirot and Miss Marple whodunits continue to appear as televised series. A new version of Murder on the Orient Express, starring David Suchet, who plays Poirot on public television in the United States, aired in this country last year. Meanwhile, Christie’s Mousetrap—a thriller centered on guests snowed in at a country hotel—is still in production at the St. Martins Theatre in London’s West End; the evening I saw it marked performance number 23,774 for the longest-running play in history.

Every year, tens of thousands of Christie’s admirers descend on Torquay, the Devon resort where the author spent her early years. They walk the seafront “Agatha Christie Mile” (“A Writer’s Formative Venue,”) that delineates landmarks of her life, from the Victorian pier, where the teenage Agatha roller-skated on summer weekends, to the Grand Hotel, where she spent her wedding night with her first husband, Royal Flying Corps aviator Archie Christie, on Christmas Eve 1914. The annual Christie Festival at Torquay draws thousands of devotees, who attend murder-mystery dinners, crime-writing workshops and movie screenings and have been known to dress as Hercule Poirot look-alikes.

And Christie’s own story is still unfolding: in 2009, HarperCollins published Agatha Christie’s Secret Notebooks, an annotated selection of her jottings, unearthed at Greenway in 2005 before renovations began there. The cache provided new insight into her creative process. “There are notes for a single novel scattered over a dozen notebooks,” says John Curran, a Christie scholar at Trinity College Dublin, who discovered the 73 notebooks after he had been invited to Greenway by grandson Mathew Prichard. “At her peak, her brain just teemed with ideas for books, and she scribbled them down any way she could.” The book also includes a never-before-seen version of a short story written in late 1938, “The Capture of Cerberus,” featuring a Hitler-like archvillain. Earlier in 2009, a research team from the University of Toronto caused an international tempest with its report suggesting that she had suffered from Alzheimer’s disease during her final years.

The restoration of Greenway has also catalyzed a reappraisal of Christie’s work. Journalists and critics visited Devon in droves when the estate opened, pondering the novelist’s enduring popularity. Some critics complain that, in contrast to such masters of the form as Arthur Conan Doyle, creator of Sherlock Holmes, or Georges Simenon, the Belgian-born author of the Inspector Maigret series, Christie was neither a prose stylist nor a creator of fully realized characters. “Her use of language is rudimentary and her characterizations thin,” Barry Forshaw, editor of British Crime Writing: An Encyclopedia, recently opined in the Independent newspaper. Christie set her novels in “a never-never-land Britain, massively elitist,” he declared; her detectives amounted to “collections of tics or eccentric physical characteristics, with nothing to match the rich portrayal of the denizen of 221B Baker Street.” To be sure, Poirot lacks the dark complexity of Sherlock Holmes. And alongside her own masterpieces, such as the novel And Then There Were None, published in 1939, Christie produced nearly unreadable clunkers, including 1927’s The Big Four. But Christie’s admirers point to her ability to individualize a dozen characters with a few economical descriptions and crisp lines of dialogue; her sense of humor, pacing and finely woven plots; and her productivity. “She told a rattling good story,” says Curran. What’s more, Christie’s flair for drama and mystery extended to her own life, which was filled with subplots—and twists—worthy of her novels.

Agatha Mary Clarissa Miller was born on September 15, 1890, at Ashfield, her parents’ villa on Barton Hill Road in a hillside neighborhood of Torquay. Her father, Frederick Miller, was the charmingly indolent scion of a wealthy New York family; because his stepmother was British, he grew up on both sides of the Atlantic. Miller spent his days playing whist at Torquay’s Gentlemen’s Club and taking part in amateur theatricals; her mother, Clara Boehmer, instilled in Agatha, the youngest of three children, a love of reading and an active imagination. “I had a very happy childhood,” she wrote in her autobiography, which she began in 1950 and completed 15 years later. “I had a home and garden that I loved; a wise and patient Nanny; as father and mother two people who loved each other dearly and made a success of their marriage and of parenthood.” Christie’s idyll disintegrated in the late 1890s, however, when her father squandered his inheritance through a series of bad business deals. He died of pneumonia at age 55 when Agatha was 11. From that point, the family scraped by with a puny income that Clara received from the law firm of her late father-in-law.

Agatha grew into an attractive, self-confident young woman, the belle of Torquay’s social scene. She fended off a dozen suitors, including a young airman, Amyas Boston, who would return to Torquay 40 years later, as a top commander in the Royal Air Force. “He sent a note to Christie at Greenway requesting a meeting for old times’ sake,” says John Risdon, a Torquay historian and Christie expert. “And he got a reply back saying no thanks, she would rather have him ‘cherish the memory of me as a lovely girl at a moonlight picnic...on the last night of your leave.’” She had, says Risdon, “a thread of romanticism that went right through her life.” In 1912 she met Archie Christie, an officer in the Royal Flying Corps, at a Torquay dance. They married two years later, and Archie went off to France to fight in the Great War. During his absence, Agatha cared for injured soldiers at Torquay’s hospital, then—in a move that would prove fateful—she distributed medicinal compounds at a local dispensary. That work alerted her to the “fascination for poison,” wrote Laura Thompson in her recent biography, Agatha Christie: An English Mystery. “The beautiful look of the bottles, the exquisite precision of the calculations, the potential for mayhem contained within order” captivated the future crime writer.

By the time Christie tried her hand at a detective novel, in 1916, “I was well steeped in the Sherlock Holmes tradition,” she would recall in her autobiography. The story she devised, a whodunit set in motion by a strychnine poisoning, introduced some of her classic motifs: multiple suspects and murder among the British upper classes—as well as a Belgian refugee who helps Scotland Yard solve the case. Poirot “was hardly more than five feet four inches, but carried himself with great dignity,” Christie wrote in her promising debut, The Mysterious Affair at Styles. “His head was exactly the shape of an egg, and he always perched it a little on one side. His moustache was very stiff and military. The neatness of his attire was almost incredible; I believe a speck of dust would have caused him more pain than a bullet wound.” Four years later, by which time Christie was living in London with Archie and their infant daughter, Rosalind, the publishing firm Bodley Head accepted the manuscript. They offered a small royalty after the first 2,000 books were sold, and locked Christie in for an additional five novels under the same terms. “Bodley Head really ripped her off,” says Curran.

Then, in 1926, Christie experienced a series of life-changing turns. In June of that year, The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, her sixth novel, was published by William Collins to critical acclaim and far more generous remuneration. The book, notable for its surprising denouement—Poirot exonerates the original suspects and identifies his own assistant, the story’s narrator, as the murderer—“established Christie as a writer,” says Curran. That summer, Archie announced that he had fallen in love with his secretary and wanted a divorce. And on December 4, Agatha Christie’s Morris car was found abandoned at the edge of a lake near the village of Albury in Surrey, outside London, with no sign of its owner. Her disappearance set off a nationwide manhunt that riveted all of England. Police drained ponds, scoured underbrush and searched London buses. The tabloids floated rumors that Christie had committed suicide or that Archie had poisoned her. Eleven days after her disappearance, two members of a band performing at the Swan Hydropathic Hotel in Harrogate, Yorkshire, reported to police that a guest registered as “Mrs. Teresa Neele” from Cape Town, South Africa, resembled newspaper photographs of the missing writer. Tracked down by police and reunited briefly with Archie, Christie never explained why she had vanished. The never-solved mystery has, over the decades, prompted speculation that she was seeking to punish her husband for his desertion or had suffered a nervous breakdown. The episode also inspired a 1979 film, Agatha, starring Dustin Hoffman and Vanessa Redgrave, which imagined Christie heading to Harrogate to hatch a diabolical revenge plot.

In September 1930, Christie married Max Mallowan, an archaeologist she had met six months earlier on a visit to the ancient Babylonian city of Ur in today’s Iraq. The couple settled near Oxford, where she increased her literary output. In 1934, Christie produced two detective novels—Murder on the Orient Express and Why Didn’t They Ask Evans?—two short story collections, and a romance novel written under the Westmacott pseudonym. From 1935 on, British editions of her whodunits sold an average of 10,000 hardcovers—a remarkable figure for the time and place. Her popularity soared during World War II, when Blitz-weary Britons found her tidy tales of crime and punishment a balm for their fears and anxieties. “When people got up in the morning, they didn’t know whether they’d go to bed at night, or even have a bed to go to,” says Curran. “Christie’s detective novels were very reassuring. By the end the villain was caught and order restored.” Grandson Prichard told me that Christie’s tales of crime and punishment demonstrate “her belief in the power of evil, and her belief in justice.”

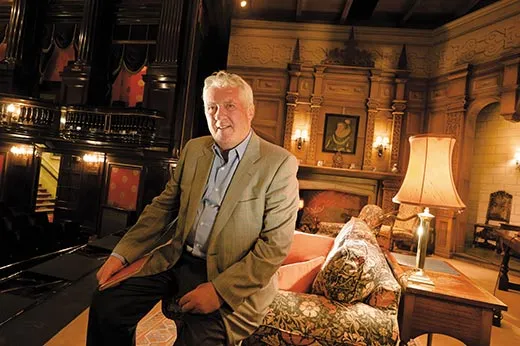

One frigid December morning, I visited Prichard in his office at Agatha Christie Limited, in central London. He greeted me in a bright room filled with framed original covers and facsimile first editions of Christie’s novels, now published by HarperCollins. Since his mother’s death, Prichard, 67, has been principal guardian of his grandmother’s legacy, screening requests to adapt Christie’s work for media from film and computer games to graphic novels, overseeing merchandising agreements, and, on occasion, taking trespassers to court. In 1977, Agatha Christie Limited filed a lawsuit against the creators of Agatha, claiming that the film, then in production, took liberties with the story of her disappearance. The company lost its case, although Prichard believes that the lawsuit probably made the film “marginally less fictional than it might have been.” More recently, Prichard approved a revival of A Daughter’s a Daughter, a loosely autobiographical drama Christie wrote as Mary Westmacott. Prichard, who attended the December 2009 opening of the play, admitted its depiction of a troubled mother-daughter relationship mirrored that of Christie and her daughter, Rosalind. Writing in the Daily Telegraph, critic Charles Spencer characterized the work as “a fascinating, neglected curiosity.”

Prichard describes his childhood at Greenway during the 1950s as “the anchor of my growing up...I used to toddle down the stairs, and my grandmother would tell me early morning stories, and she followed my career when I was at [Eton], my cricket.” He settled back in his desk chair. “I was fortunate. I was the only grandchild, so all of her attention was concentrated on me.” After dinner, Prichard went on, Christie would retire to the drawing room and read aloud from corrected proofs of her latest novel to an intimate group of friends and family. (Intensely disciplined, she began writing a novel each January and finished by spring, sometimes working from a tent in the desert when she accompanied Mallowan on digs in the Middle East.) “My grandfather’s brother Cecil, archaeologists from Iraq, the chairman of Collins and [Mousetrap producer] Peter Saunders might be there,” Prichard recalled. “Eight or ten of us would be scattered round, and her reading the book took a week or ten days. We were a lot more relaxed back then.”

Prichard says he was taken aback by the 2009 research paper that suggested his grandmother suffered from dementia during the last years of her life. According to the New York Times, the researchers digitized 14 Christie novels and searched for “linguistic indicators of the cognitive deficits typical of Alzheimer’s Disease.” They found that Christie’s next-to-last novel, published in 1972, when she was 82, exhibited a “staggering drop in vocabulary” when compared with a novel she had written 18 years earlier—evidence, they postulated, of dementia. “I said to my wife, ‘If my grandmother had Alzheimer’s when she wrote those books, there were an awful lot of people who would have loved to have Alzheimer’s.’” (For his part, scholar John Curran believes that the quality of Christie’s novels did decline at the end. “Mathew and I have a disagreement about this,” he says.)

Today, Prichard enjoys occasional visits to Greenway, posing as a tourist. He was both pleased—and somewhat disconcerted—he says, by the first-year crush of visitors to his childhood summer home. Fortunately, more than half chose to arrive not by car, but by bicycle, on foot or by ferry down the River Dart; the effort to minimize vehicular traffic kept relations largely amicable between the National Trust and local residents. But there have been a few complaints. “Hopefully the fuss will die down a little, the numbers will go down rather than up, but one never knows. It’s difficult [for the local community],” he told me.

Back at Greenway, Robyn Brown and I wander through the sun-splashed breakfast room and cozy salon where Christie’s readings took place, and eye the bathtub where, Brown says, “Agatha liked to get in with a book and an apple.” In their last years, Rosalind and Anthony Hicks had been too ill to maintain the house properly; Brown points out evidence of renovations that shored up sagging walls, replaced rotting beams, repaired dangerous cracks—and revealed intriguing glimpses of the house’s history. Standing outside the winter dining room, she gestures to the floor. “We did some digging, and found a Victorian underfloor heating system here,” she tells me. “Underneath the flue we found cobbled pavement that was in front of the Tudor court. So in fact we are standing in front of the original Tudor house.” (That house, built around 1528, was demolished by Greenway’s late 18th-century owner, Roope Harris Roope, who constructed the Georgian mansion on the site.)

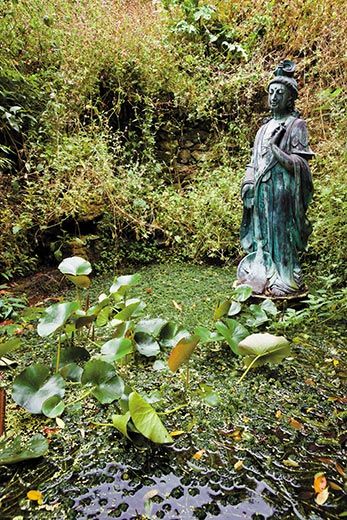

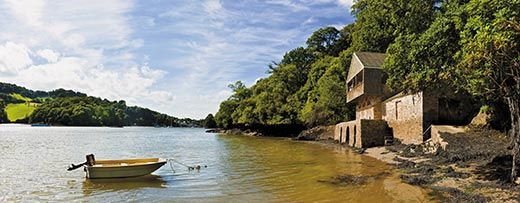

Stepping outside, we admire the house’s graceful, butterscotch-yellow facade, with its two-columned central portico and single-story wings added in 1823. Beyond a curving gravel driveway, a steep drop-off descends to the Dart. I follow a forest path for several hundred yards to a slate-roofed, stone boathouse, one of Christie’s favorite places, which sits above a sandy strip of river beach covered with clumps of black-green seaweed. In Christie’s 1956 novel, Dead Man’s Folly, Poirot joins a mystery writer, Ariadne Oliver, for a party at a Devon estate called Nasse House—a stand-in for Greenway—and there discovers the corpse of a young girl lying beside the secluded boathouse. The Battery is nearby—a stone plaza flanked by a pair of 18th-century cannons; it made a cameo appearance in Five Little Pigs.

Although the estate inspired scenes in several of her novels, Christie seldom, if ever, wrote at Greenway. It was, Brown emphasizes, an escape from the pressures of work and fame, a restorative retreat where she slipped easily into the roles of grandmother, wife and neighbor. “It’s the place where she could be Mrs. Mallowan,” Brown says. “She went to the village shop to get her hair cut, went to a fishmonger in Brixham, hired a bus and took local school kids to see Mousetrap. She was very much a part of the local community.” The opening of Greenway has shed some light on the author’s private world. But, three and a half decades after her death, the source of Agatha Christie’s genius—and many aspects of her life—remain a mystery worthy of Jane Marple or Hercule Poirot.

Writer Joshua Hammer lives in Berlin. Photographer Michael freeman is based in London.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2021-09-15_at_12.44.05_PM.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2021-09-15_at_12.44.05_PM.png)