Where to See Some of the World’s Oldest and Most Interesting Maps

Chart humanity’s course through history with these antique navigational tools

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ec/87/ec878723-2401-46d1-b47e-0fa3e5cdb329/tabula_peutingeriana.jpg)

Back when mapmaking was still a fledgling profession in the U.S., cartographers had a trick up their sleeves: they would insert fake towns into the maps they drew. Not to screw up travelers trying to navigate, but to catch copycats. Forgery was a big problem, and the practice of copying and profiting off maps created by someone else was common. But if a fake town was spotted in a competitor's map, it was easy to prove copyright infringement.

The first fake town to appear was Agloe, New York, which appeared in the 1930s on a map by the General Drafting Co. It then reappeared on maps produced by Rand McNally when mapmakers for the company found someone had started a business at the exact spot of the fictitious Agloe and named it the Agloe General Store—thereby making the town “real.”

Fake towns are a relatively recent invention in the overall history of maps, though. The oldest known maps began to appear in about 2,300 B.C.E., carved into stone tablets. We’re not sure if any fake towns appear on the maps below, but here are six of the world's oldest or first of their kind that you can go see today.

Imago Mundi – British Museum, London, UK

More commonly known as the Babylonian Map of the World, the Imago Mundi is considered the oldest surviving world map. It is currently on display at the British Museum in London. It dates back to between 700 and 500 BC and was found in a town called Sippar in Iraq. The carved map depicts Babylon in the center; nearby are places like Assyria and Elam, all surrounded by a “Salt Sea” forming a ring around the cities. Outside the ring, eight islands or regions are carved into the tablet. The map is accompanied by a cuneiform text describing Babylonian mythology in the regions depicted on the stone.

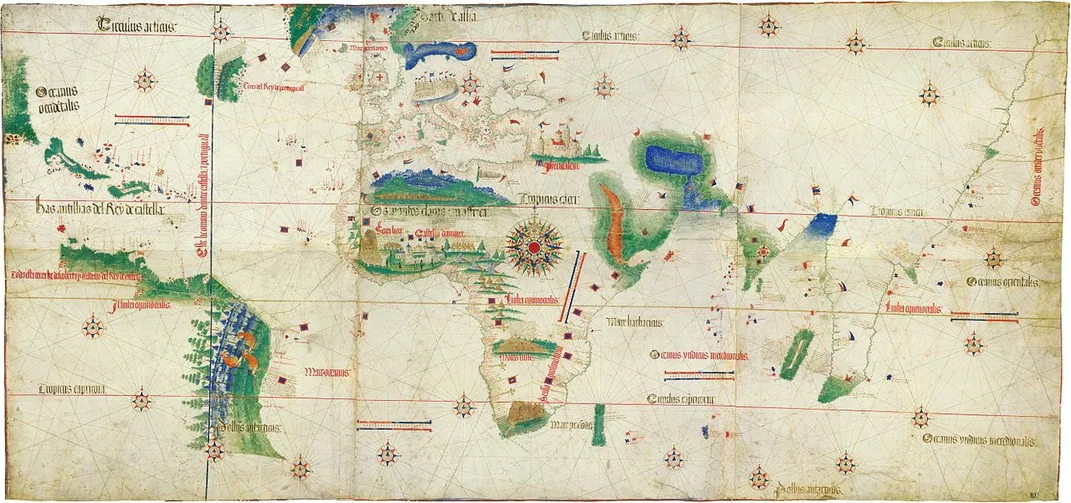

The Cantino Planisphere – Galleria Estense, Italy

This 1502 map, created by an unknown Portuguese mapmaker in Lisbon, was once the subject of international espionage. It’s named after Alberto Cantino, an Italian who was an undercover spy for the Duke of Ferrara. Though no one’s entirely sure exactly how Cantino acquired the map, we do know from historical records that he paid 12 gold ducats for it—a pretty substantial amount back then. But the important thing about this map is not that it was technically stolen goods. Rather, it included several firsts for maps at the time: it was the first in history to include the Arctic Circle, the equator, the tropics, and the border between Portuguese and Spanish territories. It also has the first named depiction of the Antilles and potentially the first image of Florida’s lower coastline. The Planisphere was stolen again in the mid-1800s and later found again; now it’s on display in the Galleria Estense in Italy.

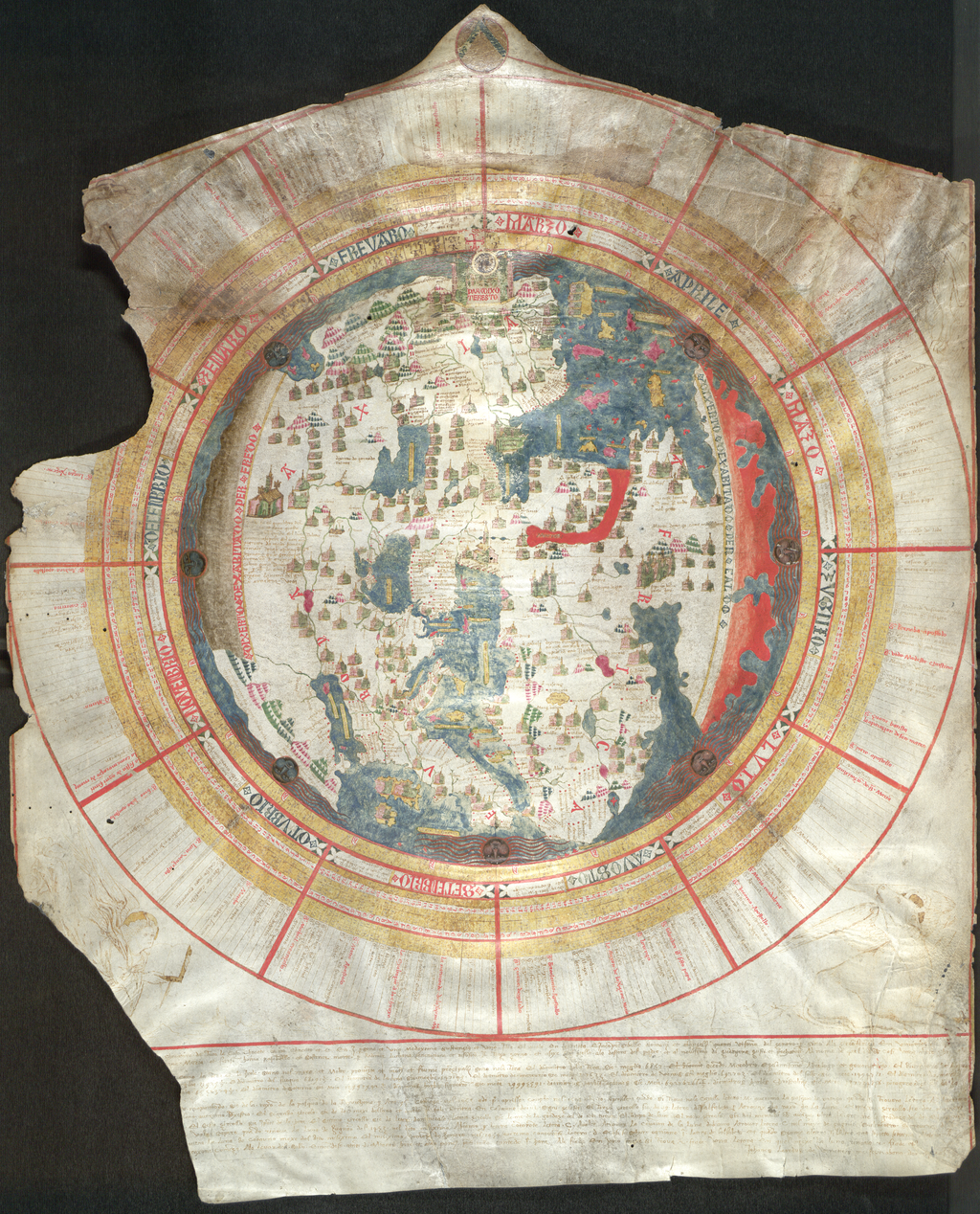

Mappamundi – American Geographical Society Library, Milwaukee, Wisconsin

This is the oldest world map in the collection at the American Geographical Society Library, a facility that has more than 1.3 million pieces in the archive. It was drawn in 1452 as one of only three world maps Venetian cartographer Giovanni Leardo drew and signed. Jerusalem is at the center of the map, which depicts the European view of the world during the Middle Ages. It was the first map of its time to show clearly defined shorelines of the Mediterranean and western Europe. The Mappamundi could also be used as a sort of calendar. Ten circles showing the dates of Easter for a 95-year period, from April 1, 1453, to April 10, 1547, surround the map itself. The rings also show moon phases, the months, zodiac signs, festivals, certain Sundays throughout the time period, and day length. The map is available upon request, if it's not part of a traveling exhibition at the time.

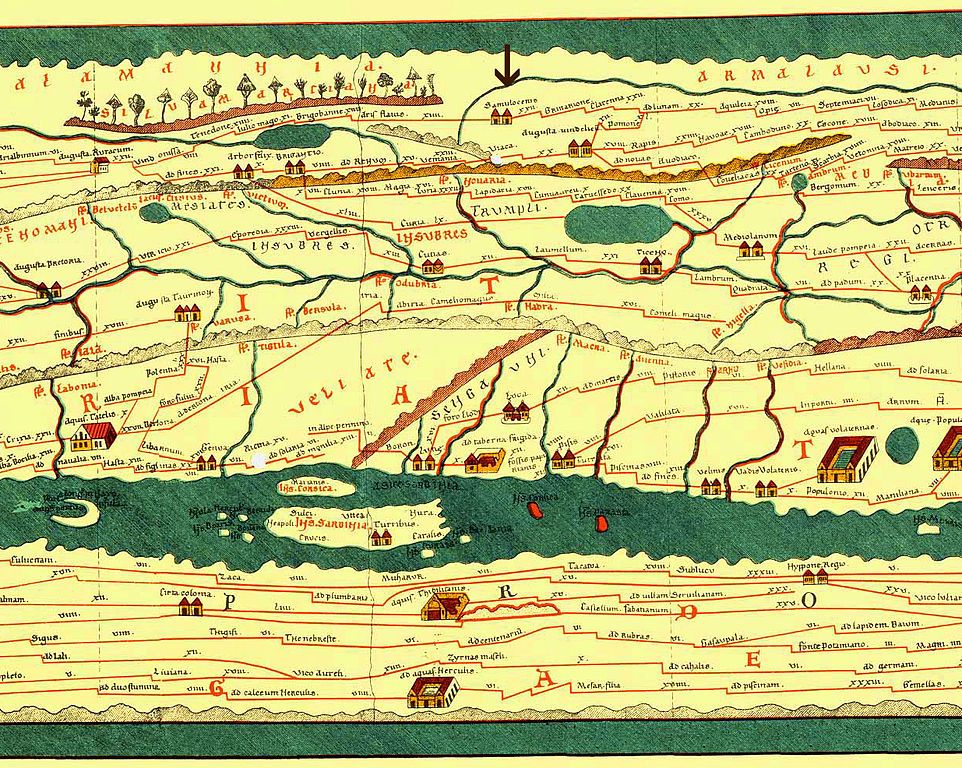

Tabula Peutingeriana – Austrian National Library, Vienna, Austria

The version of this map on display at the Austrian National Library is not actually the original, which was created in the 4th or 5th century—but it’s a close second, a replica created in the 13th century by a monk. Essentially, this is a roadmap (the earliest example of what would evolve into the modern roadmap) of the ancient Roman Empire, stretching out 22 feet wide and tracking all the public roads from the Atlantic Ocean to modern-day Sri Lanka. Each road is marked at intervals that represent a day’s travel, which can vary from 30 to 67 miles, depending on the road. The paths lead through more than 550 cities and 3,500 named places and geographical landmarks. For travel distances, this map is great; but if someone is looking for a real geographical representation of ancient Rome, look elsewhere, because the top and bottom are smushed down to fit onto the lengthy chart.

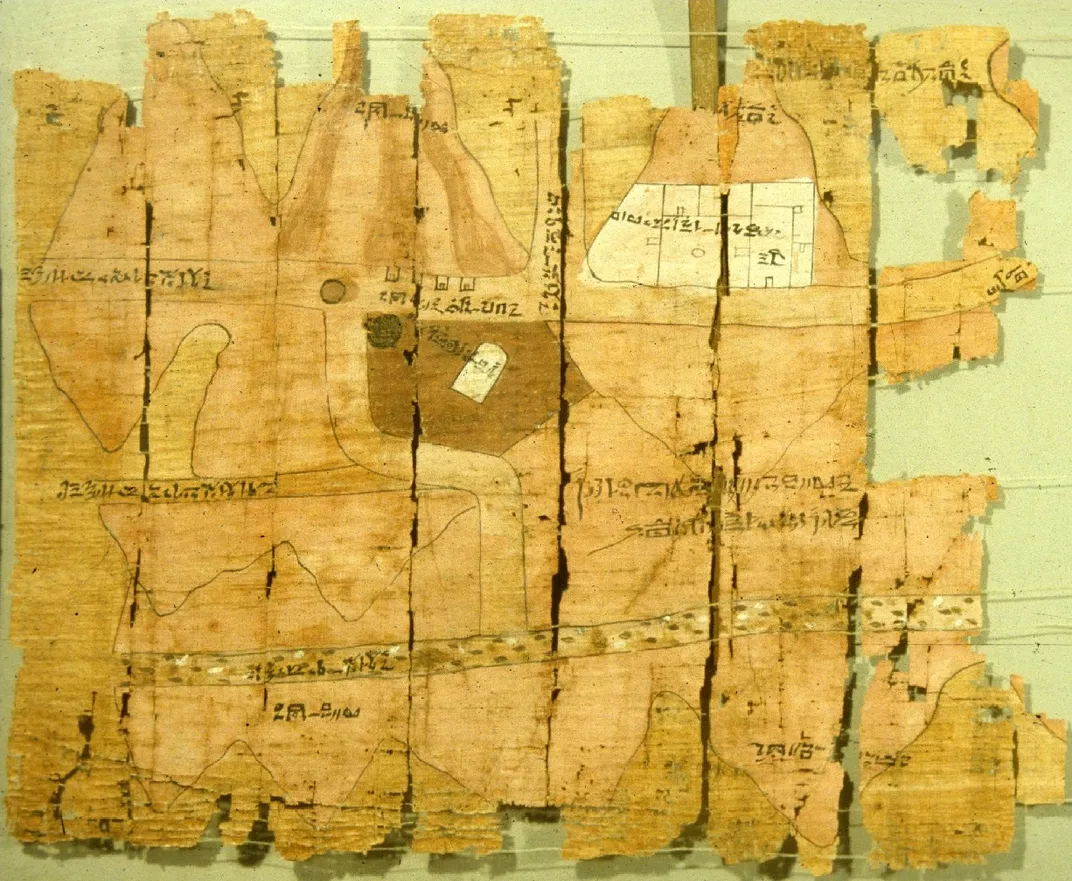

Turin Papyrus Map – Museo Egizio, Turin, Italy

This may be one of the earliest geographical maps in the world, designed to lead an expedition through part of ancient Egypt. Amennakhte (also spelled Amennakht), a well-known scribe at the time, drew the map around 1150 BC for a quarry expedition to Wadi Hammamat ordered by King Ramses IV. The men on the trip were expected to bring back blocks of stone for statue carvings of the gods and famous Egyptians at the time. The Turin papyrus has been studied since it was discovered in the early 1800s in a private tomb near modern-day Luxor. When found, the map was broken into three separate pieces of papyrus; now it survives in fragments pieced together and displayed as one sheaf in the Museo Egizio.

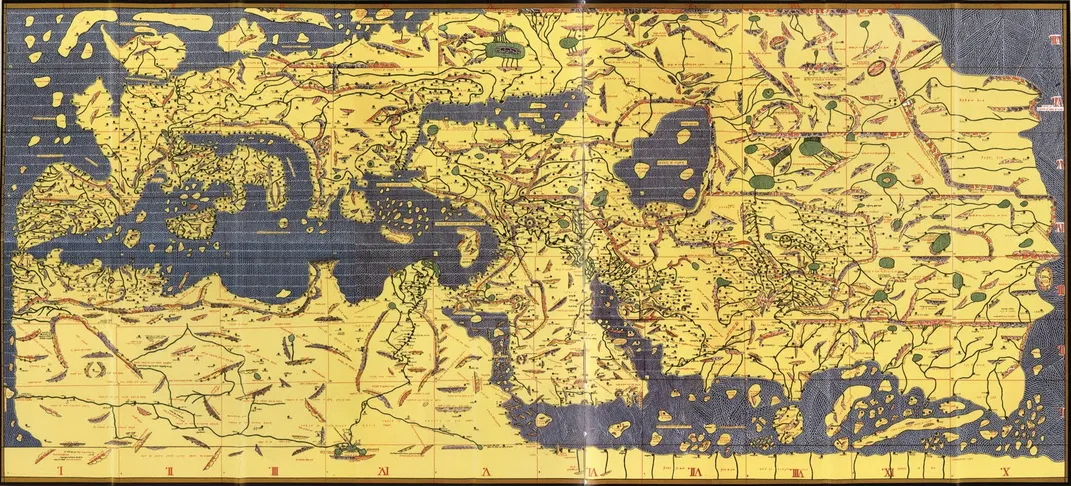

Tabula Rogeriana – University of Oxford, Oxford, UK

When cartographer Muhammad al-Idrisi created this map in 1154 for King Roger II of Sicily, he was the first to break the known world down to a more granular level with 70 smaller regional maps dictated by Ptolemy’s seven climate zones, and 10 different geographical sections. Every section has not only the map, but also a description of the land and the indigenous people there. And it was done well—so well, in fact, that it was the map of record for about 300 years for anyone looking to see a span from Africa to Scandinavia and China to Spain. The map is currently in the University of Oxford’s collection, and though it’s a copy of the original, it’s not that much newer; this one was made around 1300.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JenniferBillock.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JenniferBillock.png)