Where Travelers Go to Pay Their Respects

The Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum is not a fun place to go, yet tourists flock here, and toother somber sites around the world

Arbeit macht frei: At the iron gates of the Auschwitz prison camp, a sign translated into English reads “labor makes you free.” Today, the site is a memorial and museum, where 30 million tourists have come to see the grounds where so many people met their deaths. Photo courtesy of Flickr user adotmanda.

People have traveled for many, many reasons. They have traveled to explore, to discover and to rediscover. They have traveled to eat and to drink, to attend college and to skip college; to protest war, to wage war and to dodge war; to make music and to hear music; to pray and to do yoga; to climb mountains, go fishing, go shopping, find love, find work, go to school, party, gamble and, sometimes, just to get away from it all. Some travel for the thrill of coming home again. Some people have traveled to die.

There is also a strange yet commanding allure in traveling abroad to visit the grim preserved sites of disasters and atrocities. In 2010, for instance, almost one-and-a-half million people visited the Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum, where there is often hardly a dry eye in the house. The scene of at least 1.1 million murders is funded and maintained to preserve some of the hardest evidence that remains of the Holocaust, and to offer visitors a vague understanding of what it might have felt like to be a prisoner here in 1944. We may all have read about the Holocaust, Auschwitz and the gas chambers in schoolbooks, but nothing makes it all become so real like approaching Auschwitz’s iron gates, where one may shiver at the sight of an overhead sign reading, “Arbeit macht frei.” So plainly a lie from our illuminated vantage point of the future, the words translate into, “Labor makes you free.” Inside, tour guides lead groups past waist-deep piles of eyeglasses, shoes and artificial limbs and crutches, all worn and dirty as the day they were stripped from their owners. There even remain tangled heaps of human hair, which the Germans had planned to use for making clothing. Farther through the camp, tourists see the ominous train tracks that terminate at Auschwitz, the captives’ living quarters, and the gas chambers and ovens where they met their ends. Just how many died at Auschwitz may be uncertain. Figures cited in online discussions range from just over a million people to more than four million. No, the Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum is not a fun place to go. And tourists flock here. As of 2010, 29 million people had visited.

Where else do people go to pay tribute to tragedies?

Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Perhaps never have so many people died in one place, in one instant, as in Hiroshima on August 6, 1945. That day, at 8:15 in the morning, 70,000 human lives ended. By 1950, 200,000 people may have died as a result of the bombing and its radioactive legacy. Today, the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum preserves a vivid image of that day’s horror. The numbers above do not account for the city of Nagasaki, where the bombing on August 9 caused the deaths of between 60,000 and 80,000 people. The bomb dropped on this city (it was nicknamed “Fat Man”) was said to be stronger than the Hiroshima bomb (nicknamed “Little Boy”), but the hilly terrain of Nagasaki prevented the complete destruction of the city and surely saved many lives. For those lost, a memorial museum in Nagasaki preserves the tragedy–and neither of the two terrible bombings of Japan is an event that posterity is willing to forget.

A cannon and a monument on the Gettysburg Battlefield remind us of the deadliest days of fighting in the Civil War. Photo courtesy of Flickr user Mecki Mac.

Gettysburg. One of the very bloodiest battles of the Civil War, the three days of combat at Gettysburg cost about 7,000 American soldiers their lives. Total casualties–including soldiers taken prisoner and those reported missing–amounted to 51,000. After General Lee retreated, his victorious momentum of months prior fizzled, and historians consider the Battle of Gettysburg the event that drove the outcome of the Civil War, and shaped the future of America. The battlefield has been preserved much as the soldiers in blue and gray saw it on July 1, 2 and 3 of 1863, though today it goes by the institutional moniker Gettysburg National Military Park Museum and Visitors Center. Cannons remain poised for battle, their barrels still aimed over the fields where swarms of men once moved. Statues depict soldiers in action. And row after row of headstones represent the lives lost. Other preserved Civil War battlefields include Fort Sanders, Fort Davidson, Helena, Manassas, Fredericksburg and Antietam, where more than 3,600 soldiers died on a single day.

A one-acre depression in the ground marks the spot where one of the Trade Center towers stood before it fell on September 11, 2001. Photo courtesy of Flickr user wallyg.

Ground Zero at the former New York World Trade Center. For many people living who are old enough to remember 9/11, the chronology of our world can be divided into two eras–the time before the September 11, 2001 attack on the World Trade Center, and the years that have followed. Exactly a decade after the attack, the National September 11 Memorial & Museum opened to commemorate the time and place that more than 3,000 people abruptly died in the downtown heart of one of America’s greatest cities. The site commemorating the tragedy features two depressions in the city floor where each of the Twin Towers previously stood, and visitors who have seen the buildings fall on TV scores of times may nonetheless marvel that it’s true: The two skyscrapers really are gone. Each memorial is walled with polished stone and rimmed by an unbroken waterfall that sprinkles into a pool below. The names of every victim who died in the attack are engraved in bronze plating along each pool’s perimeter. Visiting the memorial is free but requires reservations.

Wounded Knee Creek. On December 29, 1890, American soldiers marched onto the Lakota Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, in South Dakota, and strategically surrounded a camp of 350 Lakota Sioux people–most of whom were women and children. After setting up four wheel-mounted Hotchkiss guns to provide cover, a group of the soldiers advanced. Suspecting the presence of armed warriors under the leadership of Big Foot, whom the Army had been pursuing in the weeks prior, the soldiers intended to strip the Lakota of their weapons. A scuffle ensued between one soldier and a Lakota man. A shot was reportedly fired, and then panic ensued. Lakota Sioux and Americans alike began firing from all directions indiscriminately. Warriors, women and children fell dead–including the leaders Spotted Elk and Big Foot–along with 25 American soldiers (many possibly hit by “friendly” fire). Among the Lakota Sioux, 150 were dead, and the massacre–two weeks to the day after Sitting Bull was attacked and killed–marked the last major conflict between white Americans and the Sioux. An entire continent of indigenous cultures had been mostly eradicated. Today, the site of the Wounded Knee massacre is a national historic landmark.

Gallipoli Peninsula. Between April 25, 1915, and January 9, 1916, more than 100,000 soldiers died along the beaches of the Gallipoli Peninsula, in northwest Turkey. Turkish, French, English, New Zealand, Australian, German and Canadian troops all died here. Many casualties occurred during poorly arranged landings in which Turkish gunmen situated on cliffs dispatched entire boatloads of Allied soldiers before their boots had even touched the sand. Today, cemetery after cemetery line the waters of the Aegean Sea, with almost countless tombstones honoring one young soldier after another who was commanded to his death. Signs remind visitors that these public grounds are not to serve as picnic sites, which may be tempting. Sloped lawns of green-trimmed grass spread among the stones and run down to the water’s edge, where these soldiers came trampling ashore, while a plaque at Anzac Cove bears the words of the former Turkish ruler Mustafa Kemal: “Those heroes that shed their blood and lost their lives… You are now lying in the soil of a friendly country. Therefore rest in peace. There is no difference between the Johnnies and the Mehmets to us where they lie side by side now here in this country of ours… you, the mothers, who sent their sons from faraway countries wipe away your tears; your sons are now lying in our bosom and are in peace. After having lost their lives on this land. They have become our sons as well.” The Turks suffered the greatest losses during the siege–perhaps 80,000 or more soldiers killed–while the official New Zealand soldier death rate of nearly 32 percent may be an inflated statistic, according to some historians. Now, ANZAC Day (Australian and New Zealand Army Corps Day) occurs every 25th day of April, an event that draws thousands to participate in services in the nearest cities, like Eceabat, Gelibolu and Çanakkale. The 100th anniversary of the first day of the siege will take place April 25, 2015.

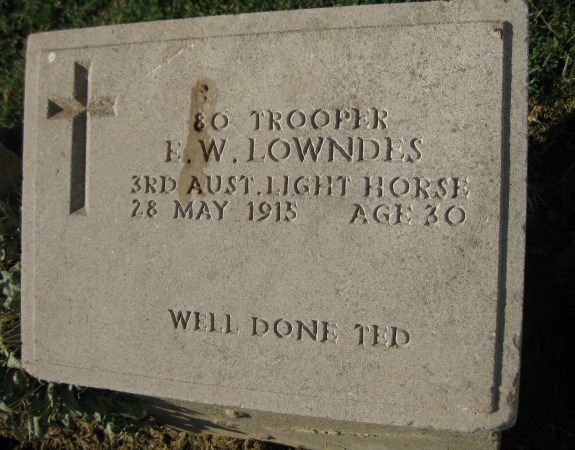

An engraved headstone honors one of almost 9,000 Australian soldiers who died on Turkish shores during the 1915 Allied assault campaign at the Gallipoli Peninsula. Photo by Alastair Bland.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Off-Road-alastair-bland-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Off-Road-alastair-bland-240.jpg)