Who Was Casanova?

The personal memoir of history’s most famous lover reveals a misunderstood intellectual who befriended the likes of Ben Franklin

Purchased in 2010 for $9.6 million, a new record for a manuscript sale, the original version of Casanova’s erotic memoir has achieved the status of a French sacred relic. At least, gaining access to its famously risqué pages is now a solemn process, heavy with Old World pomp. After a lengthy correspondence to prove my credentials, I made my way on a drizzly afternoon to the oldest wing of the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris, a grandiose Baroque edifice on rue de Richelieu near the Louvre. Within those hallowed halls, built around a pair of ancien régime aristocratic mansions, I waited by marble statues of the greats of French literature, Rousseau, Molière and Voltaire, before being led through a domed reading room filled with scholars into the private sanctum of the library offices. After traipsing up and down endless stairwells and half-lit corridors, I was eventually seated in a special reading room overlooking a stone courtyard. Here, Marie-Laure Prévost, the head curator of the manuscript department, ceremoniously presented two black archival boxes on the wooden desk before me.

As I eagerly scanned the elegant, precise script in dark brown ink, however, the air of formality quickly vanished. Madame Prévost, a lively woman in a gray turtleneck and burgundy jacket, could not resist recounting how the head of the library, Bruno Racine, had traveled to a secret meeting in a Zurich airport transit lounge in 2007 to first glimpse the document, which ran to some 3,700 pages and had been hidden away in private hands since Casanova died in 1798. The French government promptly declared its intention to obtain the legendary pages, although it took some two and a half years before an anonymous benefactor stepped forward to purchase them for la patrie. “The manuscript was in wonderful condition when it arrived here,” said Prévost. “The quality of the paper and the ink is excellent. It could have been written yesterday.

“Look!” She held up one of the pages to the window light, revealing a distinctive watermark—two hearts touching. “We don’t know if Casanova deliberately chose this or it was a happy accident.”

This reverential treatment of the manuscript would have gratified Casanova enormously. When he died, he had no idea whether his magnum opus would even be published. When it finally emerged in 1821 even in a heavily censored version, it was denounced from the pulpit and placed on the Vatican’s Index of Prohibited Books. By the late 19th century, within this same bastion of French culture, the National Library, several luridly illustrated editions were kept in a special cupboard for illicit books, called L’Enfer, or the Hell. But today, it seems, Casanova has finally become respectable. In 2011, several of the manuscript’s pages—by turns hilarious, ribald, provocative, boastful, self-mocking, philosophical, tender and occasionally still shocking—were displayed to the public for the first time in Paris, with plans for the exhibition to travel to Venice this year. In another literary first, the library is posting all 3,700 pages online, while a lavish new 12-volume edition is being prepared with Casanova’s corrections included. A French government commission has anointed the memoir a “national treasure,” even though Casanova was born in Venice. “French was the language of intellectuals in the 18th century and he wanted as wide readership as possible,” said curator Corinne Le Bitouzé. “He lived much of his life in Paris, and loved the French spirit and French literature. There are ‘Italianisms’ in his style, yes, but his use of the French language was magnificent and revolutionary. It was not academic but alive.”

It’s quite an accolade for a man who has often been dismissed as a frivolous sexual adventurer, a cad and a wastrel. The flurry of attention surrounding Casanova—and the astonishing price tag for his work—provide an opportunity to reassess one of Europe’s most fascinating and misunderstood figures. Casanova himself would have felt this long overdue. “He would have been surprised to discover that he is remembered first as a great lover,” says Tom Vitelli, a leading American Casanovist, who contributes regularly to the international scholarly journal devoted to the writer, L’Intermédiaire des Casanovistes. “Sex was part of his story, but it was incidental to his real literary aims. He only presented his love life because it gave a window onto human nature.”

Today, Casanova is so surrounded by myth that many people almost believe he was a fictional character. (Perhaps it’s hard to take seriously a man who has been portrayed by Tony Curtis, Donald Sutherland, Heath Ledger and even Vincent Price, in a Bob Hope comedy, Casanova’s Big Night.) In fact, Giacomo Girolamo Casanova lived from 1725 to 1798, and was a far more intellectual figure than the gadabout playboy portrayed on film. He was a true Enlightenment polymath, whose many achievements would put the likes of Hugh Hefner to shame. He hobnobbed with Voltaire, Catherine the Great, Benjamin Franklin and probably Mozart; survived as a gambler, an astrologer and spy; translated The Iliad into his Venetian dialect; and wrote a science fiction novel, a proto-feminist pamphlet and a range of mathematical treatises. He was also one of history’s great travelers, crisscrossing Europe from Madrid to Moscow. And yet he wrote his legendary memoir, the innocuously named Story of My Life, in his penniless old age, while working as a librarian (of all things!) at the obscure Castle Dux, in the mountains of Bohemia in the modern-day Czech Republic.

No less improbable than the man’s life is the miraculous survival of the manuscript itself. Casanova bequeathed it on his deathbed to his nephew, whose descendants sold it 22 years later to a German publisher, Friedrich Arnold Brockhaus of Leipzig. For nearly 140 years, the Brockhaus family kept the original under lock and key, while publishing only bowdlerized editions of the memoir, which were then pirated, mangled and mistranslated. The Brockhaus firm limited scholars’ access to the original document, granting some requests but turning down others, including one from the respected Austrian novelist Stefan Zweig.

The manuscript escaped destruction in World War II in a saga worthy of John le Carré. In 1943, a direct hit by an Allied bomb on the Brockhaus offices left it unscathed, so a family member pedaled it on a bicycle across Leipzig to a bank security vault. When the U.S. Army occupied the city in 1945, even Winston Churchill inquired after its fate. Unearthed intact, the manuscript was transferred by American truck to Wiesbaden to be reunited with the German owners. Only in 1960 was the first uncensored edition published, in French. The English edition arrived in 1966, just in time for the sexual revolution—and interest in Casanova has only grown since.

“It’s such an engaging text on so many levels!” says Vitelli. “It’s a wonderful point of entry into the study of the 18th century. Here we have a Venetian, writing in Italian and French, whose family lives in Dresden and who ends up in Dux, in German-speaking Bohemia. He offers access to a sense of a broad European culture.” The memoir teems with fantastic characters and incidents, most of which historians have been able to verify. Apart from the more than 120 notorious love affairs with countesses, milkmaids and nuns, which take up about a third of the book, the memoir includes escapes, duels, swindles, stagecoach journeys, arrests and meetings with royals, gamblers and mountebanks. “It’s the West’s Thousand and One Nights,” declared Madame Prévost.

Even today, some episodes still have the power to raise eyebrows, especially the pursuit of very young girls and an interlude of incest. But Casanova has been forgiven, particularly among the French, who point out that attitudes condemned today were tolerated in the 18th century. “The moral judgment never came up,” Racine told a press conference last year. “We neither approve nor condemn his behavior.” Curator Le Bitouzé feels his scurrilous reputation is undeserved, or at least one-dimensional. “Yes, he quite often behaved badly with women, but at other times he showed real consideration,” she said. “He tried to find husbands for his former lovers, to provide them with income and protection. He was an inveterate seducer, and his interest was never purely sexual. He didn’t enjoy being with English prostitutes, for example, because with no common language, he couldn’t talk to them!” Scholars, meanwhile, now accept him as a man of his time. “The modern view of The Story of My Life is to regard it as a work of literature,” says Vitelli. “It’s probably the greatest autobiography ever written. In its scope, its size, the quality of its prose, it’s as fresh today as when it first appeared.”

Tracing Casanova’s real-life story is not a straightforward quest. He obsessively avoided entanglements, never married, kept no permanent home and had no legally acknowledged children. But there remain fascinating vestiges of his physical presence in the two locations that mark the bookends of his life— Venice, where he was born, and the Castle Dux, now called Duchcov, in the remote Czech countryside where he died.

And so I began by prowling the Rialto, trying to locate one of Casanova’s few known addresses buried somewhere in Venice’s bewildering maze of Baroque laneways. Few other cities in Europe are so physically intact from the 18th century, when Venice was the decadent crossroads of East and West. The lack of motorized vehicles allows the imagination to run freely, especially in the evening, when the crush of tourists eases and the only sound is the lapping of water along the ghostly canals. But that doesn’t mean you can always track down the past. In fact, one of the paradoxes of this romantic city is that its residents barely celebrate its most noted son, as if they were ashamed of his wicked ways. (“Italians have an ambiguous attitude toward Casanova,” Le Bitouzé had told me. “He left Venice, and he wrote in French.” Kathleen Gonzalez, who is writing a walking guide to Casanova sites in Venice, says, “Even most Italians mostly only know the caricature of Casanova, which is not a subject of pride.”)

The only memorial is a stone plaque on the wall of the minuscule laneway Calle Malipiero in the San Samuele district, declaring that Casanova was born here in 1725 to two impoverished actors—although in which house nobody knows, and it may even have been around the corner. It was also in this neighborhood that Casanova, while studying for a career in the church at the age of 17, lost his virginity to two well-born teenage sisters, Nanetta and Marta Savorgnan. He found himself alone with the adventurous pair one night sharing two bottles of wine and a feast of smoked meat, bread and Parmesan cheese, and innocent adolescent games escalated into a long night of “ever varied skirmishes.” The romantic triangle continued for years, beginning a lifelong devotion to women. “I was born for the sex opposite to mine,” he wrote in the preface of his memoir. “I have always loved it and done all that I could to make myself loved by it.” His romantic tales are spiced with marvelous descriptions of food, perfumes, art and fashion: “Cultivating whatever gave pleasure to my senses was always the chief business of my life,” he wrote.

For a more evocative glimpse of Casanova’s Venice, one can visit the last of the old bàcaros, or bars, Cantina do Spade, which Casanova wrote about visiting in his youth, when he had dropped out of both the clergy and the military and was eking out a living as a violin player with a gang of loutish friends. Today, Do Spade is one of the most atmospheric bars in Venice, hidden in an alley that is barely two shoulders wide. Within the dark wooden interior, elderly men sip light wine from tiny glasses at 11 on a Sunday morning and nibble cicchetti, traditional delicacies such as dried cod on crackers, stuffed calamari and plump fried olives. On one wall, a page copied from a history book discreetly recounts Casanova’s visit here during the carnival celebrations of 1746. (He and his friends tricked a pretty young woman into thinking that her husband was in danger, and that he could be saved only if she shared her favors with them. The document details how the group “conducted the young lady to Do Spade where they dined and indulged their desires with her all night, then accompanied her back home.” Of this shameful conduct, Casanova remarked casually, “We had to laugh after she thanked us as frankly and sincerely as possible”—an example of his willingness to show himself, at times, in the worst possible light.)

It was not far from here that Casanova’s life was transformed, at age 21, when he saved a wealthy Venetian senator after an apoplectic fit. The grateful noble, Don Matteo Bragadin, virtually adopted the charismatic young man and showered him with funds, thus allowing him to live like a playboy aristocrat, wear fine clothes, gamble and conduct high society affairs. The few descriptions and surviving portraits of Casanova confirm that in his prime, he was an imposing presence, over six feet tall, with a swarthy “North African” complexion and a prominent nose. “My currency was an unbridled self-esteem,” Casanova notes in his memoir of his youthful self, “which inexperience forbade me to doubt.” Few women could resist. One of his most famous seductions was of a ravishing, noble-born nun he identifies only as “M.M.” (Historians have identified her as, most likely, Marina Morosini.) Spirited by gondola from her convent on Murano Island to a secret luxury apartment, the young lady “was astonished to find herself receptive to so much pleasure,” Casanova recalls, “for I showed her many things she had considered fictions...and I taught her that the slightest constraint spoils the greatest pleasures.” The long-running romance blossomed into a ménage à trois when M.M.’s older lover, the French ambassador, joined their encounters, then to à quatre when they were joined by another young nun, C.C. (most likely Caterina Capretta).

Which palazzo Casanova occupied in his prime is the subject of spirited debate. Back in Paris, I paid a visit to one of Casanova’s most ardent fans, who claims to have purchased Casanova’s Venetian home—the fashion designer Pierre Cardin. Now age 89, Cardin has even produced a musical comedy based on Casanova’s life, which has been performed in Paris, Venice and Moscow, and he has created an annual literary prize for European writers—the Casanova Award. “Casanova was a great writer, a great traveler, a great rebel, a great provocateur,” Cardin told me in his office. “I have always admired his subversive spirit.” (Cardin is quite a collector of real estate related to literary underdogs, having also purchased the Marquis de Sade’s chateau in Provence.)

I finally found Cardin’s Ca’Bragadin on the narrow Calle della Regina. It certainly provides an intimate glimpse of the sumptuous lifestyle of Venice’s 18th-century nobility, which lived in grandeur as the Republic’s power gradually waned. The elderly caretaker, Piergiorgio Rizzo, led me into a garden courtyard, where Cardin had placed a modern touch, a plexiglass gondola that glowed a rainbow of colors. Stairs led up to the piano nobile, or noble level, a grand reception hall with marble floors and chandeliers. In a darkened alcove, Signor Rizzo produced a rusted key and opened the door to a musty mezzanino—a half-floor that, Cardin had told me, Casanova often used for trysts. (Cardin says that this was confirmed by Venetian historians when he purchased the palazzo in 1980, though some scholars have recently argued that the mansion was owned by another branch of the illustrious Bragadin family, and that its use by Casanova was “somewhat unlikely.”)

Casanova’s charmed life went awry one hot July night in 1755, just after his 30th birthday, when police burst into his bedroom. In a society whose excesses were alternately indulged and controlled, he had been singled out by the Venetian Inquisition’s spies for prosecution as a cardsharp, a con man, a Freemason, an astrologer, a cabbalist and a blasphemer (possibly in retaliation for his attentions to one of the Inquisitor’s mistresses). He was condemned for an undisclosed term in the prison cells known as the Leads, in the attic of the Doge’s Palace. There, Casanova languished for 15 months, until he made a daring break through the roof with a disgraced monk, the only inmates ever to escape. Today, the palace’s dismal interior chambers can be visited on the so-called Itinerari Segreti, or Secret Tour, on which small groups are led through a hidden wall panel, passing through the Inquisition’s trial and torture rooms before reaching the cells that Casanova once shared with “rats big as rabbits.” Standing in one of these cells is the most concrete connection to the writer’s life in the shadowy world of Venice.

His escape made Casanova a minor celebrity in the courts of Europe, but it also heralded his first exile from Venice, which lasted 18 years. Now his career as a traveling adventurer began in earnest. One dedicated Casanovist has tracked his movements and discerned that he covered nearly 40,000 miles in his lifetime, mostly by stagecoach along grueling 18th-century roads. Styling himself the “Chevalier de Seingalt” (Casanova was the ultimate self-invented man), he made his fortune by devising a national lottery system in Paris, then squandered it frequenting the gambling houses of London, the literary salons of Geneva and the bordellos of Rome. He conducted a duel in Poland (both men were wounded) and met Frederick the Great in Prussia, Voltaire in Switzerland and Catherine the Great in St. Petersburg, all the while romancing an array of independently minded women, such as the philosophy-loving niece of a Swiss Protestant pastor, “Hedwig,” and her cousin “Helena.” (Of his fleeting passions, he observes in his memoir, “There is a happiness which is perfect and real as long as it lasts; it is transient, but its end does not negate its past existence and prevent he who has experienced it from remembering it.”)

The approach of middle age, however, would take its toll on Casanova’s dark good looks and sexual prowess, and the younger beauties he admired began to disdain his advances. His confidence was first shattered at age 38 when a lovely, 17-year-old London courtesan named Marie Anne Genevieve Augspurgher, called La Charpillon, tormented him for weeks and then scorned him. (“It was on that fatal day...that I began to die.”) The romantic humiliations continued across Europe. “The power to please at first sight, which I had so long possessed in such measure, was beginning to fail me,” he wrote.

In 1774, at the age of 49, Casanova finally obtained a pardon from the Inquisition and returned to his beloved Venice—but increasingly querulous, he wrote a satire that offended powerful figures and was forced to flee the city again nine years later. This second and final exile from Venice is a poignant tale of decline. Aging, weary and short of cash, Casanova drifted from one of his former European haunts to the next, with rare high points such as a meeting with Benjamin Franklin in Paris in 1783. (They discussed hot-air balloons.) His prospects improved when he became secretary to the Venetian ambassador in Vienna, which took him on regular journeys to Prague, one of the most sophisticated and cosmopolitan cities in Europe. But when his patron died in 1785, Casanova was left dangerously adrift. (“Fortune scorns old age,” he wrote.) Almost penniless at age 60, he was obliged to accept a position as librarian to Count Joseph Waldstein, a young nobleman (and fellow Freemason) who lived in Bohemia, in Castle Dux, about 60 miles north of Prague. It was, to say the least, a comedown.

Today, if anywhere in Europe qualifies as the end of the world, it may be Duchcov (pronounced dook-soff), as the town of Dux in the Czech Republic is now known. A two-hour train journey took me into the coal mining mountains along the German border before depositing me in what appeared to be wilderness. I was the only passenger on the decrepit platform. The air was heavy with the scent of burnt coal. It seemed less a suitable residence for Casanova than Kafka.

There was no transportation into town, so I trudged for half an hour through desolate housing projects to the only lodgings, the Hotel Casanova, and had coffee at the only eatery I could find, the Café Casanova. The historic center turned out to be a few grim streets lined with abandoned mansions, their heraldic crests crumbling over splintered doors. Drunks passed me by, muttering to themselves. Old women hurried fearfully out of a butcher’s shop.

Castle Dux, set behind iron gates next to the town square, was a welcome sight. The Baroque chateau, home to the Waldstein family for centuries, is still magnificent despite decades of Communist-era neglect. A wooden door was answered by the director, Marian Hochel, who resides in the castle year-round. Sporting a ginger goatee and wearing a duck-egg-blue shirt and green scarf, he looked more like an Off Broadway producer than a museum chief.

“Casanova’s life here in Duchcov was very lonely,” Hochel told me as we shuffled through the castle’s unheated rooms, wrapped in our overcoats. “He was an eccentric, an Italian, he didn’t speak German, so he couldn’t communicate with people. He was also a man of the world, so Duchcov was very small for him.” Casanova escaped when he could to the nearby spa town of Teplice and made excursions to Prague, where he could attend the opera and meet luminaries such as Mozart’s librettist, Lorenzo Da Ponte, and almost certainly Mozart himself. But Casanova made many enemies in Duchcov, and they made his life miserable. Count Waldstein traveled constantly, and the ill-tempered old librarian fought with the other staff—even over how to cook pasta. Villagers taunted him. Once he was struck while walking in town.

It was a dismal last act for the aging bon vivant, and he became depressed to the point of contemplating suicide. In 1789, his doctor suggested that he write his memoirs to stave off melancholy. Casanova threw himself into the task, and the therapy worked. He told his friend Johann Ferdinand Opiz, in a 1791 letter, that he wrote for 13 hours a day, laughing the whole time: “What pleasure in remembering one’s pleasures! It amuses me because I am inventing nothing.”

In this enforced solitude, the old roué mined his rich seam of experience to produce the vast Story of My Life while maintaining a voluminous correspondence to friends all over Europe—an enviable output for any writer. His joie de vivre is contagious on the page, as are his darker observations. “His goal was to create an honest portrait of the human condition,” says Vitelli. “His honesty is unsparing, especially about his loss of powers as he ages, which is still rare in books today. He is unstinting about his disappointments, and how sad his life became.” As Casanova put it: “Worthy or not, my life is my subject, and my subject is my life.”

The manuscript ends in mid-adventure—in fact, mid-sentence—when Casanova is 49 and visiting Trieste. Nobody knows exactly why. It appears that he planned to end his narrative before he turned 50, when, he felt, he ceased enjoying life, but was interrupted when recopying the final draft. Casanova had also received news in Duchcov in 1797 that his beloved Venice had been captured by Napoleon, which seemed to rekindle his wanderlust. He was planning a journey home when he fell ill from a kidney infection.

Hochel views his remote chateau as a literary shrine with a mission. “Everyone in the world knows the name of Casanova, but it is a very clichéd view,” he said. “It’s our project to construct a new image of him as an intellectual.” Using old plans of the castle, his staff has been returning paintings and antique furniture to their original positions and has expanded a small Casanova museum that was created in the 1990s. To reach it, we followed echoing stone corridors into the “guest wing,” our breath visible in the icy air. Casanova’s bedroom, his home for 13 years, was as cold as a meat locker. Portraits of his many famous acquaintances adorned the walls above a replica of his bed. But the prize exhibit is the frayed armchair in which, Waldstein family tradition holds, Casanova expired in 1798, muttering (improbably), “I lived as a philosopher and die as a Christian.” A single red rose is laid upon it—sadly artificial. The elegiac atmosphere was somewhat diluted in the next room, where a book-lined wall electronically opened to reveal a dummy of Casanova dressed in 18th-century garb hunched over a desk with a quill.

“Of course, this is not where Casanova actually wrote,” Hochel confided. “But the old library is off-limits to the public.” As darkness fell, we climbed over construction poles and paint cans on the circular stairs of the South Tower. In the 18th century, the library had been a single large chamber, but it was broken up into smaller rooms in the Communist era and is now used mainly for storage. As the wind howled through cracks in the walls, I carefully picked my way through a collection of dusty antique chandeliers to reach the window and glimpse Casanova’s view.

“The castle is a mystical place for a sensitive person,” Hochel said. “I have heard noises. One night, I saw the light turned on—in Casanova’s bedroom.”

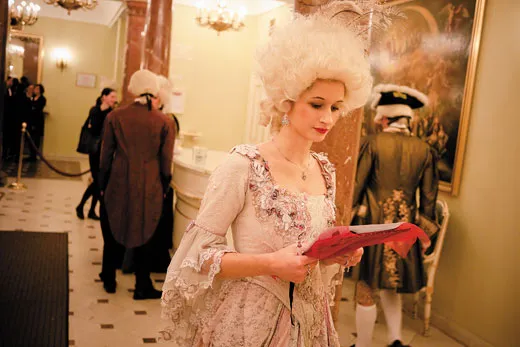

Before leaving, we went back to a humble souvenir store, where I purchased a coffee mug with a photograph of two actors in 18th-century garb and a logo in Czech: “Virgins or widows, come breakfast with Casanova!” Well, you can’t break a 200-year-old cliché overnight.

My last stop was the chapel of St. Barbara, where a tablet embedded in the wall bears Casanova’s name. In 1798, he was buried in its cemetery beneath a wooden marker, but the location was lost in the early 19th century when it was turned into a park. The tablet was carved in 1912 to give admirers something to look at. It was a symbolic vantage point to reflect on Casanova’s posthumous fame, which reads like a parable on the vagaries of life and art. “Casanova was a minor character while he was alive,” Vitelli says. “He was the failure of his family. His two younger brothers [who were painters] were more famous, which galled him. If he had not written his marvelous memoir, he almost certainly would have been forgotten very quickly.”

The few Czechs who know about Casanova’s productive years in Bohemia are bemused that his manuscript has been proclaimed a French national treasure. “I believe it is very well placed in the National Library in Paris for security and conservation,” said Marie Tarantová, archivist at the State Regional Archive in Prague, where Casanova’s reams of letters and papers, which were saved by the Waldstein family, are now kept. “But Casanova wasn’t French, he wasn’t Venetian, he wasn’t Bohemian—he was a man of all Europe. He lived in Poland. He lived in Russia. He lived in Spain. Which country the manuscript ended up in is in reality unimportant.”

Perhaps the memoir’s online presence, accessible from Mumbai to Melbourne, is his best memorial. Casanova has become more cosmopolitan than ever.

Tony Perrottet is the author of The Sinner's Grand Tour: A Journey Through the Historical Underbelly of Europe.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tony.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tony.png)