Why Winter Is the Perfect Time to Visit Bavaria

This corner of Germany is the ultimate cold-weather playground, a place where sledding down a mountain, or knocking back beers are equally worthy pursuits

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/45/31/4531d803-2fc8-47e3-b9af-2b0d89c96ccb/image.jpeg)

On Zugspitze, Germany's tallest mountain, there is surprisingly decent schnitzel. There are also life-altering views. As I stood atop a glacier, the ski town of Garmisch-Partenkirchen nearly 9,000 feet below me, I looked down at what resembled an Alpine lake but was in fact the top of a cloud. Tethered to my wrist was a toboggan, the instrument of my shame — and eventual revelation.

The main reason for my trip to this part of Bavaria, the large state that occupies Germany's southeastern corner, was to indulge a curiosity about tobogganing. For years, I'd been eager to recapture the rush I'd experienced as a child, in Moscow, sledding down the man-made crevasse in front of our Cuban Missile Crisis–era tenement. And while most Americans regard sledding as a children's pastime — as quaint as snow angels and hot cocoa — I'd read that in Germany it was a legitimate adult winter sport. According to the German Bob & Sled Federation, the country is home to about a hundred competitive clubs with 6,500 members.

I'd brought along my friend Paul Boyer as insurance against wimping out. A veteran of New York's wine industry, he made for an agreeable travel companion by possessing several crucial qualities I lacked: physical courage, an easy sociability, and a love of driving at unsafe speeds. When I confided to Paul that I was having second thoughts about ascending the Alps to sit astride a wooden rocket and plummet into an icy abyss, he laughed and said it sounded "totally rad."

We'd arrived in Munich, Bavaria's largest city, a week earlier. After emerging from a U-Bahn station, we found ourselves near the iconic domed towers of the Frauenkirche, a 15th-century Gothic cathedral. We were in the midst of a downpour, and three women in yellow rain ponchos were singing on a makeshift stage for an audience of no one. It took me a moment to recognize the words to Johnny Cash's "Ring of Fire." We hustled past this odd entertainment to the Nürnberger Bratwurst Glöckl am Dom, a traditional, wood-paneled tavern, to dry out by the hearth and sample one of the glories of Bavarian culture. The Nürnberger bratwurst is a pork sausage about the size of an American breakfast link that's grilled over a raging beechwood fire. According to some Mitteleuropean sausage mavens, the Glöckl serves the Platonic ideal of the Nürnberger — what Fauchon on Paris's Place de la Madeleine is to the macaron and Yonah Schimmel on New York's East Houston Street is to the potato-and-mushroom knish.

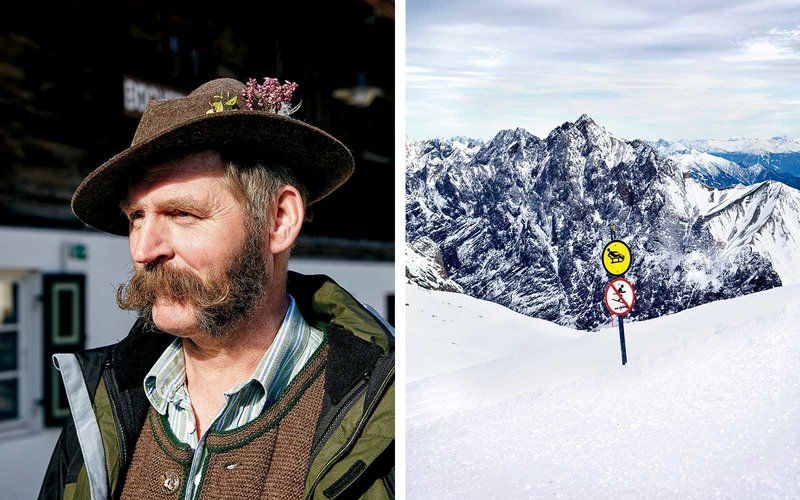

In the first-floor dining room, we sat next to men in lederhosen, knee socks, loden jackets, and felt hats decorated with feathers and pewter pins — a demographic we would encounter at every drinking establishment we visited in Bavaria. "Welcome to our strange land," whispered Willibald Bauer, a friend who hails from Munich and manufactures some of the world's finest record players several neighborhoods away. We were making short work of our glasses of Helles — the light, crisp lager native to Munich — when I asked Bauer, the product of an old local family, what made Bavarians distinct from other Germans. "A distrust of anyone except our neighbors," he answered brightly. "Also, Bavarians drink a lot of beer, and beer makes you sentimental." Just then the group in the lederhosen linked arms and began crooning a ribald folk ballad with a broad, boozy vibrato.

After lunch we headed to the Tegernsee, a lake encircled by snow-rimmed Alps that's a popular getaway for Munich residents. The hour-long southbound drive snaked along mowed fields lined with Lilliputian sheds and distant foothills. The country's longest natural toboggan course winds high above the Tegernsee, on the slopes of a 5,650-foot-tall mountain called the Wallberg. On the autobahn, a minivan carrying a family of six whipped past us so fast that it felt like we were puttering along on a hay baler by comparison.

Bachmair Weissach, a contemporary hotel decorated with the mahogany and deer skulls of a traditional hunting lodge, awaited us on the lake's southern shore. One of the restaurants inside specialized in fondue; stripped of the kitschy 1970s connotation it has in America, fondue made a lot of sense. We spent our first dinner in Germany dipping forkfuls of bread, speck, and sliced figs into a pot of tangy Bergkäse — mountain cheese — and washing it down with glasses of cold Sylvaner.

The following morning we made a trip around the Tegernsee through villages of low houses with flower-garlanded balconies. In the town of Bad Wiessee, we stopped for lunch at Fischerei Bistro, a wooden structure flanked by two bathtubs used for chilling champagne. Christoph von Preysing, the handsome thirtysomething proprietor, pointed to a fishery he operated across the lake. It was the origin of the seriously delicious char he served three ways — in a salad, as roe, and as a whole, delicately smoked fillet. Later, in a village also called Tegernsee, on the opposite shore, we applied ourselves to a softball-size, butter-hued bread dumpling in mushroom gravy and local pilsner at the Herzogliches Bräustüberl Tegernsee, a cavernous beer hall inside a former Benedictine monastery. Hundreds of locals, day-trippers from Munich, and tourists from much farther away ate and drank to the sounds of a live brass band while waitresses laden with plates of wurst and baskets of Laugenbrezeln, traditional pretzels made with lye and salt, shimmied between the tables.

That afternoon, we discovered that we would have to put our tobogganing on hold — because of unexpected warm weather, much of the snow had melted and the toboggan runs were closed. We rode the gondola to the top of the Wallberg anyway. Below us, the lake and the surrounding villages looked like a model-railroad landscape; the storybook peaks behind us receded into Austria.

According to the sweltering five-day forecast, the only place in Germany where we were certain to find tobogganing was atop Zugspitze, where the runs are open year-round. The drive there took us along the Isar River, which glowed such a luminous shade of aquamarine that we wondered whether it was rigged with underwater lights, and past Karwendel, a nature preserve roughly the size of Chicago. The landscape of jagged rock walls streaked with rugged pines and snow brought to mind the mythological operas of Richard Wagner, who spent his happiest years in Bavaria.

With history on our minds and the overture from Das Rheingold blaring in our rented BMW, Paul and I decided to make an unexpected detour to Linderhof Palace, the favorite home of Wagner's patron, King Ludwig II. Handsome and tall, the Swan King, as he was known, enjoyed making unannounced trips to the countryside and presenting the farmers he met with lavish gifts. Some locals still refer to him in the Bavarian dialect as Unser Kini — Our King. As European monarchs go, Ludwig was about as fun as they get.

Linderhof looks like a shrunk-down Versailles transplanted to a remote mountain valley. The unexpectedly dainty palace is filled to the rafters with several types of marble, Meissen china, elephant-tusk ivory, and enough gold leaf to gild a regional airport. Its most remarkable feature is a dining table that was set with food and wine in a subterranean kitchen and raised by a winch to the room above, where Ludwig preferred to eat alone. Afterward, he sometimes adjourned to the Venus Grotto, a man-made stalactite cave with an underground lake, painted to look like a scene from Wagner's Tannhäuser. There, the Bavarian king was rowed about in a gilt seashell boat while one of the first electrical generators in Europe lit the walls in otherworldly colors.

Schloss Elmau, our hotel and home base near the Zugspitze for the next four days, proved equally remarkable. It stands in a mountain valley where Ludwig's horses stopped for water on the way to his hunting lodge on one of the nearby peaks. It is a vast, rambling structure anchored by a Romanesque tower, but our rooms were located in a newer, posher building called the Retreat. As we pulled up, a young woman in a dark suit approached our car and, in an aristocratic London accent, said, "Welcome, Mr. Halberstadt." She led us inside a spacious common area trimmed in dark wood and filled with Chinese tapestries, shelves of hardcover books, and precisely trained spotlights, then onto a deck with a view of a mountain that jutted up into the clouds. When I inquired about checking in, our guide informed me that nothing as mundane as check-in existed at the Schloss Elmau, and that we were welcome to go up to our rooms at any time.

Mine turned out to be a rambling suite with Balinese and Indian accents, discreet motion-sensor lights, and a 270-degree vista of the valley. (Later, I discovered that when the Schloss hosted the G7 summit in 2015, my suite was occupied by Shinzo Abe, the prime minister of Japan.) Despite the sumptuous rooms and numerous restaurants, saunas, and heated pools, the Schloss manages the trick of appearing neither forbidding nor gaudy. Studied yet casual touches — a shelf of board games, piles of art books with worn spines — defuse one's awareness of the impeccable, laborious service happening just out of sight.

As it turned out, the books I saw everywhere were more than an affectation. The Schloss contains three private libraries and a large bookstore. The latter is staffed by Ingeborg Prager, a tiny septuagenarian fond of red wine and cigarettes, whose main function at the Schloss Elmau, as far as I could tell, was to engage guests in conversations about books. Elsewhere, several halls host more than 220 performances a year by classical and jazz musicians, some world-renowned. The cultural program also includes intellectual symposia, readings, and mystifying events like Bill Murray reciting the poems of Emily Dickinson and Walt Whitman while accompanied by a string trio.

I learned about the unlikely history of the place from its owner, Dietmar Müller-Elmau. The Schloss was a lark of his grandfather, Johannes Müller, a Protestant theologian and best-selling author of philosophical and spiritual treatises. Financed in 1914 by a countess who admired Müller's teachings, it was intended as a retreat for visitors to transcend their egos by walking in nature and dancing vigorously to classical music. Eventually, Müller's philosophical legacy was muddied by his vocal admiration for Hitler, and after the war the Schloss became an American military hospital and later a sanatorium for the Jewish victims of the Nazi regime. When Müller-Elmau took over the property, which was being run by his family as a barely profitable hotel, he saw it as an albatross. "But eventually I became interested in hotels," he told me. Today, the Schloss is a reflection of his many odd and exacting thoughts about hospitality, décor, and culture.

Other sights awaited us. Located a 20-minute drive away, Garmisch-Partenkirchen is a quaint town best known for hosting the 1936 Winter Olympics. It is dominated by a sinister-looking stadium surrounded by monumental sculptures of athletes. Luckily, not all of it is grim. One night, we headed there for dinner at Husar, where Paul and I made short work of the impossibly light veal schnitzel and confit of quail with beet carpaccio prepared by chef Verena Merget. Her husband, Christian, uncorked a single-vineyard dry Riesling from Schlossgut Diel in Nahe that tasted like a cocktail of limes and quartz dust. Then he opened another.

The morning we went to Zugspitze, we found our car waiting for us outside the Retreat. In Garmisch, we parked by the unnervingly fast gondola, which shot us to the top of Zugspitze at an almost vertical incline; a smaller lift brought us to the glacier. A surly man at the equipment-rental counter shot me a funny look when I asked for a wooden sled. "Only pregnant mothers rent those," he grumbled in accented English, then snickered when I asked for a helmet. Paul and I walked into the thin air dragging small plastic toboggans. A diagram on the wall had explained that you steered them by leaning back and lowering a foot into the snow. This looked dangerously unscientific.

I made the first run haltingly down a gentle slope, lurching from side to side and finally coming to an ungraceful stop at the bottom. I wiped the snow from my face and trudged back up. After several descents I began to get the hang of steering around corners and felt the joyous tingling in the solar plexus I'd recalled from my childhood.

"You know this is the kiddie slope, right?" Paul said. He was waiting for me at the top, grinning evilly. A sign beside him contained a line drawing of a woman and a small child on a sled.

A short walk away, the grown-up slope plunged nearly straight down and then twisted out of sight. While I squinted at it apprehensively, a man in glasses and a green parka hopped on a toboggan and sped away. At the bottom of the first descent, the toboggan went out from under him and skittered onto the adjacent slope, nearly taking out a group of skiers. The man came to a halt on his back with his limbs splayed, looking like a beached starfish. I looked at Paul.

"Come on," he said, "this will be awesome!" I searched inside myself but received only a mournful, definitive no. "Your loss, dude," Paul said, and shot down the slope. I watched his jacket grow smaller as he whizzed out of sight. Just then I regretted inviting him. I bit my lip and trudged away shamefully. A short while later I saw Paul walking toward me, his arms raised in triumph. "I scored weed on the ski lift," he shouted.

We agreed to meet later and I meandered back to the kiddie slope, pulling the toboggan behind me. The sun warmed my face and ahead of me the snow seemed to merge with the sky, making it look like I was walking on the roof of the world. Soon my mood lifted, too. I realized that I wanted sledding to remain in childhood, where it could keep singing its nostalgic song. Like hot cocoa and tonsillitis, it was something better left in the past. At the top of the kiddie slope I sat on the toboggan and pushed myself down the hill. By the time I got to the bottom, my face plastered with snow, I'd found what I'd come looking for.

**********

How to Explore Bavaria

Getting There

This corner of Germany is renowned for its medieval villages, fairy-tale castles, hearty food, and outdoor pursuits — especially tobogganing in the winter. To get there, fly to Munich, the state capital, where you can rent a car and explore the region's scenic rural roads at your own pace.

Hotels

Hotel Bachmair Weissach: Located an hour south of Munich, this rambling, comfortable resort has a Zen-meets-hunting-lodge vibe, several good restaurants, and stunning mountain views. The property provides easy access to skiing and tobogganing on the Wallberg. Doubles from $302.

Schloss Elmau: This grand hotel, hidden in an Alpine mountain valley about an hour west of Bachmair Weissach, is an utterly singular Bavarian experience. Daily concerts, numerous spas, nine restaurants, and a bookstore on the premises are just part of the story. Doubles from $522.

Restaurants

Fischerei Bistro: Impeccable local seafood served on the shores of the Tegernsee.Entrées $11–$39.

Herzogliches Bräustüberl Tegernsee: A rollicking beer hall in a former monastery, this spot can't be beat for its Laugenbrezeln — traditional pretzels made with lye and salt — and people-watching. Entrées $8–$15.

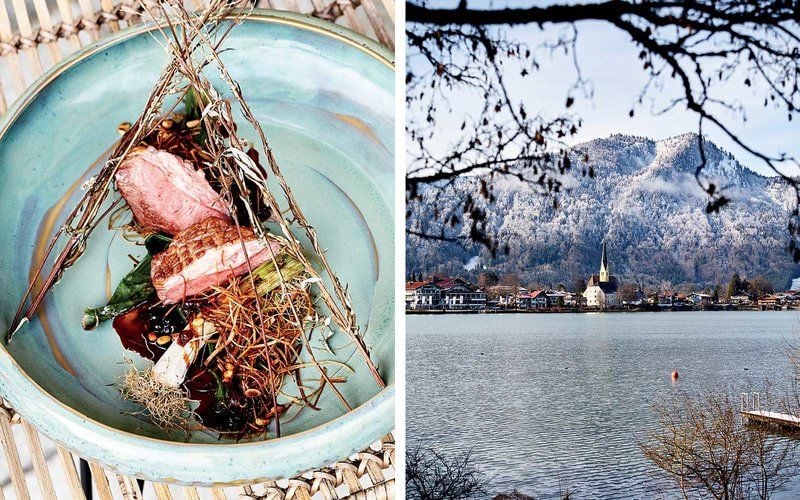

Luce d'Oro: Schloss Elmau's Michelin-starred restaurant serves refined yet approachable food alongside a colossal wine list. Entrées $26–$57.

Nürnberger Bratwurst Glöckl am Dom: A beloved institution famous for its wood-grilled Nürnberger sausages and fresh Helles beer — with décor seemingly unchanged since the time of King Ludwig II. Entrées $8–$32.

Restaurant: In this sky-blue house covered in 200-year-old murals, chef Verena Merget's flavorful Bavarian cooking pairs perfectly with a beverage program deep in German wines. Entrées $23–$46.

Restaurant Überfahrt: At the only Michelin three-starred restaurant in Bavaria, you can enjoy regionally influenced food in a modern dining room. Tasting menus from $266.

Activities

Linderhof Palace: Though the popular Venus Grotto is closed for restoration, the extensive formal gardens surrounding this Rococo 19th-century schloss in the Bavarian Alps are as compelling as the rooms inside. Tickets from $10.

Wallberg: In addition to Germany's longest toboggan run, this mountain claims unparalleled views of town and lake below. Take the gondola up at any time of year for breathtaking Alpine panoramas. Lift tickets from $12.

Zugspitze: Nearly 10,000 feet above sea level, the country's tallest peak offers year-round tobogganing on natural snow — plus equipment rental, rustic restaurants, and a wealth of facilities. Lift tickets from $52.

This story originally appeared on Travel + Leisure.

Other articles from Travel + Leisure:

- This German Town Is Covered in 72,000 Tons of Diamonds

- These Brewery Hotels Offer in-room Taps and Malted Barley Massages

- Why Telluride Just Might Be America's Coolest Ski Town

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.