Years ago, long before COVID-19 kept us all home, I drove from Los Angeles to New York City with a friend. We took off that first day with every intention of following a route that took us northward, through Chicago. About an hour into the trip we suddenly realized that heading north wasn’t possible. We simply could not live with ourselves if we drove across the country and didn’t stop to visit Graceland, Elvis’ home in Memphis. After all, what’s a road trip without the stops?

The King’s digs turned out to be one of many iconic stops along the way that defined our trip. We discovered roadside gems like the burlesque shrine Exotic World in Helendale, California (now the Burlesque Hall of Fame in Las Vegas), and the Devil’s Rope Museum dedicated to barbed wire in McLean, Texas. Over the last few months as we’ve all been lamenting the fates of once-bustling restaurants or movie theater chains or gyms, I started thinking about the truly little guys—not Graceland, but the ghost town museums or the historic Route 66 diners with rusty signs that survive mainly because of the influx of spring and summer travelers on the roads each year. If we’re not stopping in, what will become, I wondered, of these rough-and-tumble crown jewels of Americana.

Take the National Mustard Museum in Middleton, Wisconsin, opened in 1992 by Barry Levenson, a former Assistant Attorney General for the State of Wisconsin. He got the idea for the museum after his beloved Red Sox lost the 1986 World Series, when he was wandering around a late-night convenience store in a funk. He came upon the mustard aisle and, like a yellow thunderbolt, inspiration struck. The idea percolated for a bit, and he even argued a case before the Supreme Court with a tiny jar of mustard in his pocket, for luck. He won the case, opened the museum, and left law a few years later to pursue his condiment passion full-time.

“It’s not exactly the Louvre or the Guggenheim, but it has been an adventure,” Levenson says of his ever-growing display of over 6,000 jars, bottles and tubes of mustard from all 50 states and 70 countries. It has become a beloved destination for seekers of quirky attractions and, of course, mustard. The museum, which normally sees about 35,000 visitors per year, also has a popular “tasting bar” where, in the past, people could sample diverse flavors (Levenson has tried everything from root beer mustard to chocolate mustard from Sweden). When the pandemic hit and Wisconsin ordered a statewide shut down, the National Mustard Museum closed its doors for two months. They’re open now with limited capacity, staff and hours, but no tasting bar.

“You can’t taste mustard over Zoom,” says Levenson.

All of the summer tour groups canceled their visits, which Levenson calls a “devastating blow,” and the museum turned its annual street festival, which attracts up to 7,000 people, into a virtual event. With few people adding to the museum’s donation box, and sales in the gift shop down, Levenson says he thinks online orders will help keep them going until the roads fill up and the tour buses come back. “I think we’ll survive,” he says. “It’s been difficult, but in some ways, we’re finding ways to reinvent ourselves.” He says the silver lining is that their Mustard Day livestream in early August attracted visitors from all over the world who might not have known about the museum otherwise.

Across the country, in Smithfield, North Carolina, the Ava Gardner Museum, dedicated to the hometown Hollywood icon and Oscar-nominated star of films like The Night of the Iguana and The Killers, has faced similar challenges. Signs along the highway beckon travelers to stop in and spend some time with Gardner memorabilia, including costumes from famous films and a Derringer pistol from The Night of the Iguana, which was given to each cast member. The museum had to close shop on March 16, and they’re still waiting for the governor to give them the go-ahead to open up.

Lynell Seabold, director of the museum, says she was drawn to Ava Gardner because “she was forward-thinking and independent, and back then it wasn’t popular for women to be independent.” Seabold says tour buses full of seniors, younger travelers who love classic Hollywood, and curious drivers passing through the town visited the museum in years past. They would get about 5,000 visitors per year, and saw an uptick in 2019, before the pandemic. Since the closure she’s been working to update the space with plexiglass dividers and intensive sanitizing protocols to get ready for the reopening. She doesn’t anticipate a flood of crowds for some time, but she did decide to “go for broke” and mount an ambitious exhibit for the fall, which includes a heritage tour of historical sites from Ava’s life around town, in the hopes that travelers will return.

Like the Ava Gardner Museum, Baltimore’s American Visionary Art Museum (AVAM) has been closed since March. The 67,000-square-foot museum’s extensive collection of artworks spanning painting, drawing, sculpture, embroidery, and more (plus two sculpture gardens and an outdoor summer movie theater) doesn’t exactly constitute a tiny roadside attraction, but it is, at its core, a tribute to American folklore, full of works by self-taught artists who pursue their passions outside the mainstream. One of the museum’s most talked about sculptures is a 15-foot replica of the Lusitania ship by artist Wayne Kusky that’s made out of more than 200,000 toothpicks.

Rebecca Hoffberger, founder and curator of the museum, says of their eventual reopening, “It’s a transitional time for the world, so we’re just going to try our best.”

Like the smaller roadside attractions that bring a sense of history or whimsy or creativity to the country’s roads, AVAM has become a destination for travelers who want to experience unexpected American artworks created by people outside the establishment, whose talents were only recognized and given serious attention with the help of AVAM. Hoffberger got the idea for the museum in 1984 while working in the psychiatry department at Sinai Hospital in Baltimore. She was inspired by the creativity and imagination of some of the patients she worked with, and the museum became a labor of love that’s turned into her life’s passion.

“Everything we do is about what it is to be a human being, and it’s about the influential powers that either uplift or debase humanity. You have to be fiercely creative to make positive evolutionary change,” she says, which is what the collection is all about. “People say it’s the most healing place they’ve ever been.”

Like many places, the museum has had to cancel large events and groups, but they’re looking ahead and hoping for the best. A new “Science and Mystery of Sleep” exhibit opens this fall, anchored by fantastical, handmade bedroom installations created by three visionary artists, plus work that illuminates the latest scientific and artistic research about sleep and its impact on the imagination. AVAM is counting on the fact that once they’re able to open their doors to the public, people will drive to see it.

On the other end of the spectrum, a roadside spot like the famed Madonna Inn, built in 1958 and located in San Luis Obispo, California, has been able to open up and even bounce back since their initial shutdown in March. The popular destination, known for its colorful, eccentric aesthetic (think waterfall showers, rock walls in the rooms, pink-carpeted spiral staircases) relies heavily on road trippers, and the hotel’s marketing manager, Amanda Rich, says occupancy is up to about 70 percent during the week, and nearly full capacity on weekends. But in April, she says, “We had numerous weeks with occupancy below 15 percent. I don’t think it has ever been that low.”

Over the course of the summer they’ve been able to get back to a full staff instead of working with a smaller crew, and both of their restaurants are open for outdoor dining and takeout. The spa, fitness center and Jacuzzis are still closed, but they’re monitoring the situation daily and adjusting with the times.

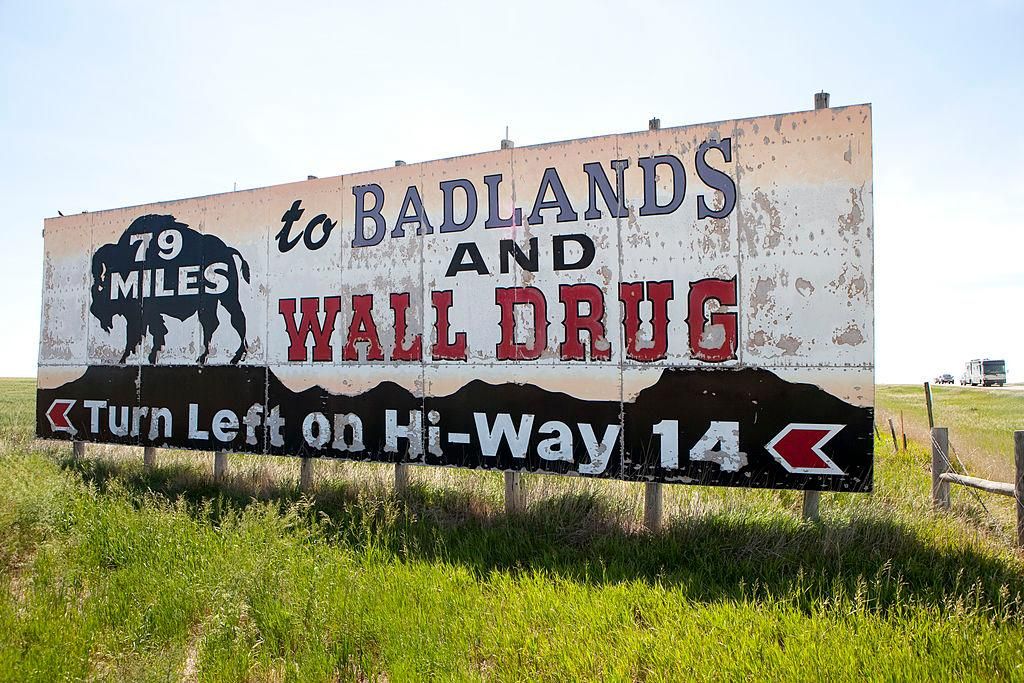

Over 1,500 miles from the Madonna Inn, at the edge of the South Dakota Badlands, sits Wall Drug, one of the country’s oldest and most historic roadside stops. Started in 1931 during the Great Depression by a local pharmacist named Ted Hustead, the store has grown from a tiny, struggling pharmacy (back then the Husteads lived in the back of the store with their son Billy) to a 76,000-square-foot wonder complete with a “Roaring T-Rex” statue, a “mining and panning experience,” a giant jackalope, and, of course, the working pharmacy.

Wall Drug is a true mom-and-pop, with Rick Hustead and his daughter now running the store that his grandparents built from scratch. People used to stop in for the free ice water as they drove through the Badlands along the hot, dusty highway. Now there are over 350 signs along more than 400 miles of road from Minnesota and Wyoming, beckoning tourists to check out Wall Drug (and get some ice water). Their coffee still costs a nickel, and their donuts, according to Hustead, are legendary.

“The pandemic has been a huge challenge for us,” says Hustead. Wall Drug closed its doors in March, but stayed open for curbside service, reducing staff by 40 percent and implementing safety protocols like plastic shields and sanitizing stations. As of July, the store is fully open again, but they’re still operating with a 40 percent reduction in staff. In 89 years of business, they never had to shut down for such a length of time. Slowly but surely, though, the roads are getting busier and travelers are stopping. “Our donuts are famous in South Dakota,” Hustead says. “When we closed people were asking us to hand them out on the street.”

Doug Kirby, one of the co-founders of RoadsideAmerica.com, which tracks over 15,000 roadside attractions across the country, says that people have been declaring the end of the golden age of tourism for years, but he doesn’t see it declining, even after this pandemic (and even after Yelp reports that 55 percent of businesses that have closed since March 1 have shuttered for good.)

“They might be having a rough time,” Kirby says of the motels and diners and offbeat museums dotting America’s roads. “Attractions are pretty nimble, though. They’re probably having economic issues they never dreamed of having, but they’re seasonal so they’re used to ebbs and flows.” He says that he and his colleagues have been getting messages from travelers out on the roads this summer. Instead of flying somewhere for their summer vacation, people are piling into the car. “People need to get out,” he says.

Whether it’s this summer or next, road trips might sound safer to some than braving an airport and sitting on a plane with strangers. Eventually, we’ll feel comfortable stopping into places like Wall Drug or the Ava Gardner Museum, just maybe with more hand sanitizer, safer protocols and a vaccine. As for that Devil’s Rope Museum of barbed wire in the Texas Panhandle that I visited years ago on my own cross-country trip, they’ve stayed completely shut down since March, waiting for the day they feel it’s safe to open up.

“I’m taking things about 15 days at a time,” says Delbert Trew, a retired rancher and owner of the Devil’s Rope Museum. “It’s been tough on everybody, but we just have to hunker down. The world is going to keep on turning.”

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/59/ca/59ca449e-1bb1-4dac-91da-35783d053a39/wall_drug_dinosaur-mobile.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/50/59/5059bbce-32aa-4d81-a2b7-1c6155a76118/wall_drug_dinosaur-social.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Dina-Gachman-bio-photo.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Dina-Gachman-bio-photo.jpg)