The Winding History of the Maze

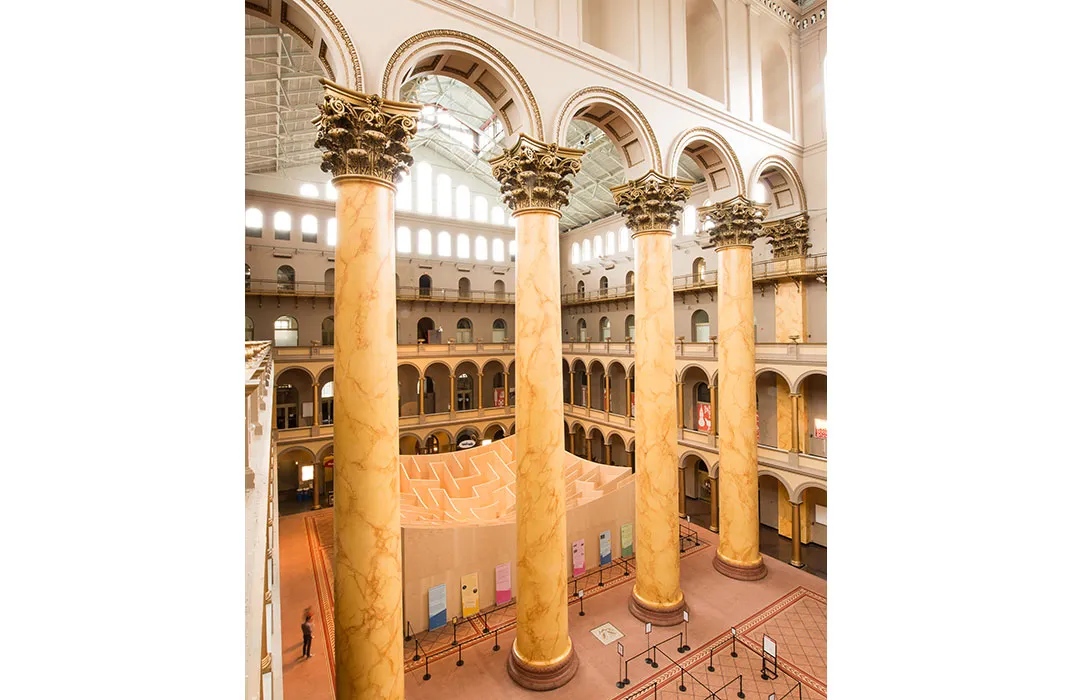

Love the idea of getting lost in crooked pathways? Check out the National Building Museum’s summer installation

They can be made of hedges, corn, wood or mirrors. They can be spiritually calming or visually stimulating, and they can incite feelings of panic, excitement or serenity. Mazes have been a part of human culture for thousands of years—but what compels us to wander through winding pathways in order to find a single, hidden exit?

Mazes have an ancient history spanning thousands of years—though the first mazes weren't mazes at all, but labyrinths, with a single winding path not meant to confuse or puzzle the way we think of traditional mazes. Labyrinths were first designed as spiritual journeys to guide the visitor along a single path, twisting yet serene. The first recorded labyrinth comes from Egypt in the 5th century B.C.; the Greek historian, Herodotus, wrote that "all the works and buildings of the Greeks put together would certainly be inferior to this labyrinth as regards labor and expense." One of the most famous labyrinths of antiquity is the Cretan Labyrinth, which housed the terrifying Minotaur at its center. The Roman Empire often employed labyrinthine motifs on their streets or above their doors, almost always accompanied by images of a Minotaur at the center—the labyrinths were thought to represent the protection of fortification.

Other labyrinths have been found in ruins of northern European cultures—it is believed that Nordic fisherman, for instance, might have walked labyrinths before heading out to sea as a way of ensuring a plentiful haul and safe return. In Germany, young men would walk through labyrinths as they approached adulthood.

After the fall of the Roman Empire, most labyrinths took on a decidedly religious nature. No longer were they three-dimensional walled structures; instead, they could be found painted on the floors and walls of religious enclaves. The meaning of these labyrinths remains mysterious, though several theories exist. Some believe that the winding path was meant to symbolize the difficult life of an early Christian. Others feel that the labyrinths were meant to depict the entangling nature of sin. Still others believe that the labyrinths were used to create a sort of "mini-pilgrimage" that a parishioner would take if they committed a small sin.

During the Middle Ages, labyrinths evolved from spiritual journeys to amusing pastimes. As kings and queens built up elaborate gardens, they would often include some sort of hedge maze as a diversion for themselves and guests. Mazes have retained their close relationship with gardens ever since—today, most public mazes exist in the form of hedge mazes or corn mazes, the latter being a distinctly American invention. England, with its long tradition of gardening, has 125 mazes open to the public.

In the United States, the most famous mazes—and the largest—are made from corn. But when the National Building Museum in Washington, D.C. wanted to do something special for their summer programming, they weren't afraid to shake-up expectations about public mazes.

"Traditionally mazes are disorienting," says Cathy Crane Frankel, vice president for exhibitions and collections at the museum. "We wanted to turn the idea of a traditional maze on its head a little bit. Our maze has elements of the normal, but it’s a little bit unexpected."

Unexpected, in no small part, thanks to the maze's architect, the Danish-born Bjarke Ingels, partner of Bjarke Ingels Group, the Copenhagen and New York-based firm that designed the maze. Crane Frankel asked Ingels to become involved with the maze project while working with the architect on another project for the museum (an exhibit about the architectural process). It didn't take much convincing—Ingels agreed to the project hours after being asked.

The maze went through a few design stages, with working designs ranging from a maze made of PVC pipes to one made of mirrors. In the end, Ingels settled on a traditional square maze, 60 feet by 60 feet and 18 feet high all on the corners—with one interesting addition. The maze dips in from its high corners, sloping to a mere three and a half feet at its center. It's a unique design for a maze, which is often meant to confuse visitors all the way through. Instead, the Building Museum's maze reveals itself at the center, allowing visitors to gain a sense of place and space before embarking back toward the tall edges and the exit.

"We’re always about peeling the layers away of any structure, and this does that on a basic level," says Frankel. Visitors can also gain an interesting perspective of the maze by ascending to the museum's second and third floors, which offer an entertaining aerial view of the maze.

The maze, which will be open every day through September 1, is part of a larger plan created by the Building Museum to utilize their interior space in public ways—to effectively serve as a town-square for D.C.'s downtown district. On its opening weekend—over the 4th of July holiday—the maze attracted over 3,000 visitors.

"The draw has been great. You get a ticket and you can go through as many times as you like in the day. It's been a really nice flow of people. It's been nice to watch people in their playing hide and seek or getting purposefully lost, or trying to master the route," says Frankel. "We're really excited to welcome new visitors, and people that don't necessarily know us or know what we do."

----

The BIG Maze is open every day until September 1. Tickets are available in person on a first-come first-served basis. For non-members of the museum, tickets are $16 for adults and $13 for youths aged 3-17, students with ID and seniors (60+). The National Building Museum is located at 401 F St NW, Washington, D.C. For inquiries, call (202) 272-2448.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/natasha-geiling-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/natasha-geiling-240.jpg)