Winter Palace

The first major exhibition devoted to the Incas’ fabled cold-weather retreat highlights Machu Picchu’s secrets

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Machu-Picchu-631.jpg)

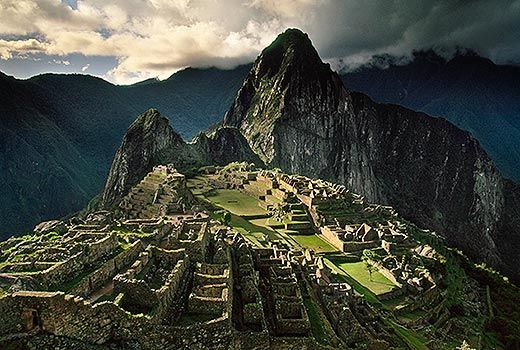

Although I had seen many images of Machu Picchu, nothing prepared me for the real thing. Stretching along the crest of a narrow ridge lay the mesmerizing embodiment of the Inca Empire, a civilization brought to an abrupt and bloody end by the Spanish conquest of the 1500s. On either side of the ruins, sheer mountainsides drop away to the foaming waters of the UrubambaRiver more than a thousand feet below. Surrounding the site, the Andes rise in a stupendous natural amphitheater, cloud-shrouded, jagged and streaked with snow, as if the entire landscape had exploded. It is hard to believe that human beings had built such a place.

It was more difficult still to grasp that Machu Picchu remained unknown to the outside world until the 20th century. It was only in 1911 that a lanky, Hawaii-born professor of Latin American history at Yale named Hiram Bingham—with two friends, several mules and a Peruvian guide—set out through the Andes, hoping to find clues to the fate of the Incas. The defeated remnants of that warrior race had retreated from the conquistadors in the direction of the Amazon basin. Bingham had been warned (with some exaggeration) that he was entering a region inhabited by “savage Indians” armed with poison arrows. Instead, he stumbled across the most extraordinary archaeological find of the century. The name Machu Picchu, or OldMountain, comes from the Quechua Indian term for the 9,060-foot peak looming over the site.

Now many of the items that Bingham collected there nearly a century ago—including richly embellished pottery vessels, copper and bronze jewelry, intricately carved knives unseen except by scholars for more than eight decades—are on view in the first major exhibition devoted to the Inca site ever mounted in the United States. “Machu Picchu: Unveiling the Mystery of the Incas” remains at Yale University’s Peabody Museum of Natural History, in New Haven, Connecticut, through May 4, before traveling the next month to Los Angeles, then on to Pittsburgh, Denver, Houston and Chicago.

“The exhibition will change the way people see Machu Picchu,” says archaeologist Richard Burger who, in collaboration with archaeologist Lucy Salazar, curated the show. “We’re going to break through the myths,” he adds. “The exhibition will remove Machu Picchu from the ‘world’s-mostmysterious- places’ category and show us the humanity of the Incas, the rhythms of daily life for both the elite and the common folks.”

The site’s spectacular setting, the drama of its discovery and Bingham’s melodramatic speculations regarding the Incas’ fate have all contributed to the legend of a mysterious “lost city.” For nearly a century, travelers and dreamers have elaborated exotic theories about its genesis, beginning with Bingham’s assertion that Machu Picchu was home to a cult of vestal virgins, who “found [there] a refuge from the animosity and lust of the conquistadors.

Although Bingham never encountered any poison-arrowtoting natives, his explorations were not without their hairraising moments. In the early summer of 1911, tracing “a trail which not even a dog could follow unassisted,” his small party hacked its way through dense tropical jungle and along slippery cliffs. A single misstep could have pitched them hundreds of feet to their deaths. After weeks of arduous trekking, they encountered a peasant who informed Bingham that some ruins might be found on a nearby mountain. “When asked just where the ruins were, he pointed straight up,” Bingham later wrote. “No one supposed that they could be particularly interesting. And no one cared to go with me.”

On July 24, after crossing the Urubamba on a rickety bridge, crawling on his hands and knees “six inches at a time,” he struggled up a snake-infested mountainside through nearly impenetrable thickets. “Suddenly,” he would recall, “I found myself confronted with the walls of ruined houses built of the finest quality of Inca stone work. . . . It fairly took my breath away. What could this place be?”

As with most modern visitors, I traveled to Machu Picchu by train from Cuzco, the old Inca capital less than 70 miles away, though it took nearly four hours to reach Aguas Calientes (Hot Waters), the village nearest to Machu Picchu, named for the thermal baths located there. My companion, Alfredo Valencia Zegarra, one of Peru’s most eminent archaeologists, had begun digging at Machu Picchu in the 1960s. The train chugged across a landscape of somnolent villages, and narrow, terraced valleys where farmers, in the tradition of their Inca ancestors, tilled the ancient Andean crops, maize and potatoes. As we descended—Machu Picchu, nearly 3,000 feet lower than Cuzco, lies on the eastern edge of the Andes—the vegetation grew denser, the valleys more claustrophobic. Stone cliffs towered hundreds of feet overhead. Alongside the tracks, the Urubamba surged over boulders and beneath treacherous-looking footbridges anchored on stone abutments that date from Inca times.

From Aguas Calientes, an unpaved road twisted up the mountain to Machu Picchu itself, where we at last came upon the vision that left Hiram Bingham speechless 92 years ago. When he first explored here, the jungle had almost entirelyengulfed the ruins. Since then, the overgrowth has been hacked away, making it easy to discern the plan the Incas followed in laying out the community. Two more or less distinct quadrants lie separated by a series of small grassy plazas. “The Inca envisioned all things in duality: male and female, life and death, right and left, the upper world and the lower world,” said Valencia, a stocky, amiable man of 62, as he bounded over ruined walls and craggy trails that would have challenged the equilibrium of a llama. “One can distinguish here an urban sector and an agricultural sector, as well as the upper town and the lower town. The temples are part of the upper town, the warehouses the lower, and so on.”

The Incas were just one of a host of minor tribes until the early 15th century. Then, gripped by a messianic belief that they were destined to rule the world, they began conquering and assimilating their neighbors. The Incas had a genius for strategy and engineering: they pioneered methods of moving large armies via road networks they constructed through the Andes. By the 16th century, their reach extended almost 2,500 miles, from present-day Colombia to central Chile.

According to Richard Burger, Machu Picchu was probably established between 1450 and 1470 by the Inca emperor Pachacuti as a royal preserve, a sort of Inca Camp David. Here, members of the royal family relaxed, hunted, and entertained foreign dignitaries. Other scholars, including Valencia, believe that Machu Picchu may have served also as a district center for administering recently conquered lands on the eastern slope of the Andes. In either case, Valencia says, the site was situated at the nexus of important Inca trails, connecting the highlands and the jungle, in a region rich in gold, silver, coca and fruits.

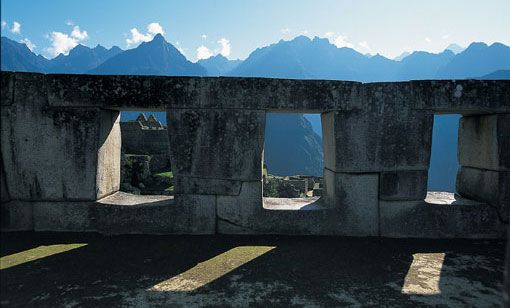

Apart from a few tourists, and llamas roaming at will through the ruins, their soft, melancholy faces peering at us over the ancient walls, Valencia and I wandered alone. We made our way along narrow cobbled lanes, through the roofless shells of temples, workshops, storehouses and houses where the grandees of the Inca world once dwelled. Hundreds of stone terraces descended the slopes. Ruins seemed to bloom out of the blue-granite boulders that littered the landscape. In many cases, laborers had chiseled these huge rocks in place to form temple walls, stairs, altars and other architectural elements.

At the height of Pachacuti’s reign, most of these buildings’ interior walls would probably have been covered in yellow or red plaster. The temples may well have been lavishly painted with the cryptic figures that survive today in the patterns of this region’s exquisite woven fabrics. And of course, five centuries ago, crowds, garbed in distinctive regional dress, including elaborate garments made of alpaca and vicuña and dyed in brilliant colors, would have thronged the streets. (According to Yale’s Lucy Salazar, the Inca Empire was multiethnic. The inhabitants of Machu Picchu constituted a microcosm of that world. “We have found the remains of individuals from as far away as Ecuador, Lake Titicaca and the Pacific coast, as well as the Andean highlands.”)

In the empire’s heyday, Machu Picchu teemed with life. On any given day, stonecutters chiseled walls for new buildings, and metalworkers hammered jewelry for the imperial treasury. Caravans of llamas arrived, laden with supplies from distant regions, while local farmers, bent beneath loads of maize and potatoes, carried their harvest into the city. Byways bustled with royal couriers and soldiers. Envoys of the emperor, borne on litters, were preceded by royal retainers, who swept paths before their masters.

Spanish-colonial chronicles describe day-to-day existence for the imperial entourage. The emperor and his nobles often banqueted in ritual plazas—with mummies of their ancestors beside them, in accordance with tradition, which held that the dead remained among the living. Dozens of acllas, or chosen women, prepared and served platters of roast alpaca, venison and guinea pig, to be washed down by chicha, or fermented maize. It was these young maidens who gave rise to the legend, promoted by Bingham, that Machu Picchu was home to a cult of “Virgins of the Sun.”

At the luminous heart of this activity, of course, was the emperor himself, whom the Incas believed to be the physical offspring of their most powerful deity, the sun. Pachacuti (He Who Shakes the Earth), who reigned from 1438 to 1471, is regarded as the greatest Inca ruler, credited with creating an administrative system essential to maintaining an empire. Pachacuti’s residence is only a shell today, but it nevertheless manages to suggest the luxury that royalty enjoyed in an age when ordinary citizens lived in windowless, one-room huts. Spacious even by modern standards, the royal quarters housed interior courtyards, rooms of state, private bathrooms and a separate kitchen. (So sacred was the emperor’s person, reported the Spanish, that attendant acllas burned garments after he wore them, lest anything that touched his body be contaminated by contact with lesser mortals.)

And yet Machu Picchu was not, in any modern sense, a city. There were no factories, shops or markets. Indeed, there was likely no commerce at all: the emperor, who laid claim to everything produced within his realm, redistributed food and clothing among his subjects as he deemed fit. While defense may have played a role in the selection of Machu Picchu’s site—the region had only recently been subdued, and enemies, the wild tribes of the Amazon basin, lived only a few days’ march away—the ritual-obsessed Incas must also have designed it with the sacred in mind.

To the Incas, the mountains were alive with gods that had to be placated with ongoing offerings of maize, chicha or meat. Occasionally, in times of famine or disaster, human beings were sacrificed. The most sacred site within Machu Picchu was the Intihuatana (Hitching Post of the Sun), a massive stone platform located at the highest point of the city. At the center of this great terrace lay a revered sculpture, a stylized mountain peak chiseled from a block of granite that may have served as a kind of calendar. “The Intihuatana was a device to control time, a sort of spiritual machine,” Valencia says, standing on the lofty platform. “If I were an Inca priest, I would be carefully watching how the sun moved month by month, studying its relation to the mountains. In effect, I would be reading the calendar, determining when crops should be planted, harvested and so on.”

Archaeologists place the population of Machu Picchu at somewhere between 500 and 750, more in winter when the imperial entourage came to the lower altitude retreat to escape the chill of Cuzco. (Farmers who raised food for the settlement probably lived nearby. Cuzco’s population was between 80,000 and 100,000; the total population of Peru was perhaps eight million.) Though Bingham speculated that Machu Picchu took centuries to build, current thinking has it completed in 20 to 50 years—lightning speed by preindustrial standards. The explanation, says Valencia, lies with the “limitless labor available to an Inca ruler.”

The Incas apparently continued to occupy Machu Picchu, at least for a short time, after the Spanish conquest. Archaeologists have found the remains of horses, which were introduced into Peru by the conquistadors, as well as a few Spanish-made trinkets, probably brought to Machu Picchu by travelers from the capital. New construction seems to have been under way when the settlement was abandoned. But why did everyone disappear? And where did they go?

Machu Picchu was made possible only by the fabulous wealth of the imperial elite. When the Spaniards decimated the ruling class, in the 1530s, survivors would likely have fled into hiding. Some may have moved to new lowland towns that the Spanish founded. Others probably returned to homes in other parts of Peru. Once Machu Picchu was abandoned, it virtually disappeared. The only evidence that the Spanish even knew about it are brief references in two colonial documents. Wrote one Spanish official: “This night I slept at the foot of a snowcapped mountain . . . where there had been a bridge from ancient times that crossed the River Vitcos to go to . . . Pichu.”

By the 1570s, the Spanish conquest of Peru was more or less complete. The old Inca world gradually slipped away. Sacred shrines were razed or converted to churches, ritual plazas turned into market squares. Harsh punishment was meted out to those who persisted in the old beliefs and practices. Still, the Inca legends survived, molded into the shapes of ceramics, woven into the patterns of textiles.

And nostalgia for Inca times still infuses Peruvian culture. Discouraged by their nation’s crumbling economy and chaotic politics (President Alberto Fujimori, accused of corruption, fled to Japan in November 2000), many Peruvians idealize Inca rule as a kind of Camelot. To this day, amid Machu Picchu’s ruins, villagers make offerings of coca leaves, cigarettes, liquor and cookies, gifts of prayer to the gods of the mountains. Or perhaps to the invisible Incas themselves, who Peruvians believe will someday return in all their glory.

And what of Hiram Bingham? He returned to Machu Picchu twice during the 1910s to conduct field research, eventually shipping hundreds of artifacts home to the PeabodyMuseum at Yale. He reluctantly ended his work in the region in 1915, only when he was accused by Peruvians— unjustly, as it turns out—of stealing tons of gold. (In fact, what gold there might once have been at Machu Picchu had probably been removed to buy the freedom of the last real Inca emperor, Atahuallpa. He was taken prisoner by the Spaniards, only to be executed in spite of the fabulous ransom the Incas had collected by stripping sites across Peru.) Bingham became lieutenant governor of Connecticut in 1922 and a U.S. senator in 1924. To his last days he remained convinced, wrongly, that he had discovered both the legendary birthplace of the Incas and their secret capital, Vilcabamba, where legends say they hid from the Spanish for years after the conquest.

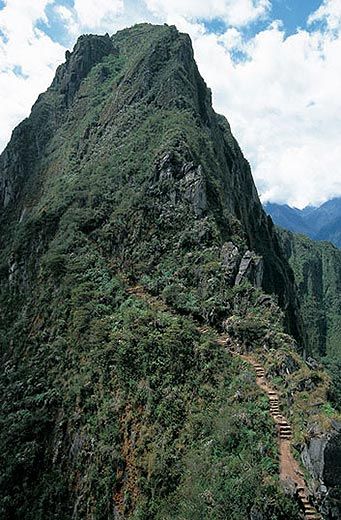

One morning, Valencia and I climbed Huayna Picchu (YoungMountain), the peak that towers 600 feet over Machu Picchu. From our starting point, it was impossible to discern the switchback path that levered itself up a narrow cleft in the cliff face, through clumps of orchids, yellow-flowering yucca and spiny shrubs. At times, the trail, cut from stone, seemed more like a ladder than ascending stairs, each rung no broader than the width of my foot. At the summit lay the ruins of several Inca structures, at least one a temple. From the peak’s wind-whipped crest, the traces of old Inca trails were visible, disappearing down into the jungle. Valencia said more ruins lay hidden below, among the trees, unexplored, unmapped. “There are still mysteries here,” he said. “There is more to discover, much more.”

GETTING THERE

American Airlines flies from Miami to Lima, where connecting flights to Cuzco leave daily. Start with the official Peruvian tourism office. A good read is Hugh Thomson’s The White Rock: An Exploration of the Inca Heartland.

INSIDE TIP: Stay at Cuzco’s 5-star Hotel Monasterio, a lovingly restored 17th-century colonial seminary located in the heart of the old city. Prices range from $290 to $335 per night.

CHOICE COLLECTIBLE: Extraordinarily beautiful textiles with centuries-old Inca designs are abundant in Cuzco. Prices are reasonable, and bargaining is expected.

FOR THE GOURMET: The Incas were connoisseurs of cuy, or roast guinea pig. It is available at restaurants in Cuzco and Aguas Calientes.

YOU SHOULD KNOW: You can’t ride a llama to Machu Picchu on the 26-mile Inca Trail; the animals can carry only about 100 pounds. (You can also reach the ruins by train or helicopter.) Still, if you choose to trek with one of these surefooted “Ships of the Andes,” the beast will happily carry your duffel.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.