The World’s Oldest Zoo Is a Modern Attraction With a Storied Past

The Austrian destination has a lot more to offer than exotic animals

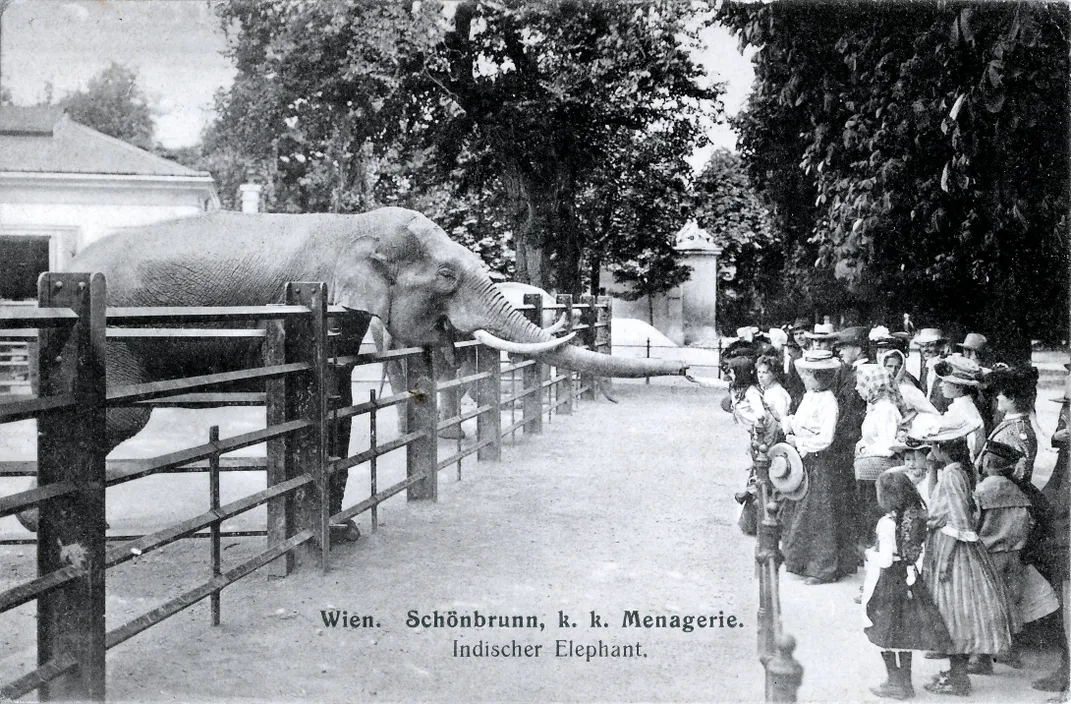

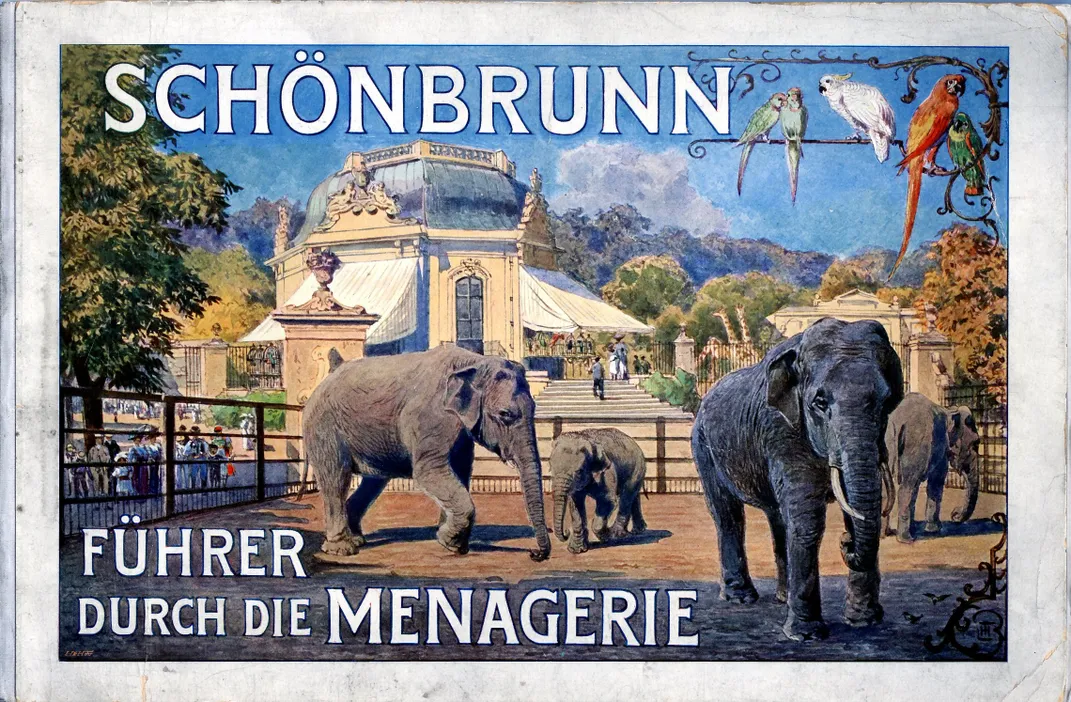

The year: 1752. The place: Schönbrunn Palace, the summer residence of his majesty Franz Stephan I of Lorraine. Stephan was new to Vienna, having married an empress, and he wanted to bring his collection of exotic animals with him. So he built a menagerie using his private funds, filling it with exotic birds, monkeys, and other creatures. An octagonal pavilion sat at the center, surrounded by 13 animal enclosures and lushly painted with scenes from Ovid’s Metamorphoses.

At the time, collections of wild animals were common in royal courts throughout Europe. They were stocked with animals brought back from exploratory missions financed by ruling families and provided an opportunity to show off their acquisitions as the Enlightenment brought the natural sciences into focus.

The Vienna zoo, however, is the one that endured—today, it’s the world’s oldest. According to the zoo’s historian, Gerhard Heindl, the other menageries were temporary. “Most of them were closed after the death of the emperor who founded them,” he tells Smithsonian.com.

But things were different in Vienna: After Franz Stephan’s death, his son and his wife’s successor, Joseph II, increased the variety of animals found at the park. Joseph added carnivores, which his father reportedly avoided because of their odor. He also ensured that visitors would always be welcome at the park, enshrining this promise in a motto that can still be seen above the park’s gate: “A place of recreation dedicated to all the people by their Esteemer.”

Today, modern operations coexist with their historic setting. Scientific research and conservation efforts now animate the zoo as much as a desire to preserve the rich history of the environs. “It’s been developing for more than 250 years,” says Heindl. “The task of the modern zoo is completely different from the task of the menagerie at its founding.” And it shows: The zoo was both the birthplace of the first elephant sired in a European zoo (in 1906) and the first elephant sired using frozen sperm and artificial insemination (in 2013). From 18th-century murals in the central pavilion to endangered species in the animal enclosures, the Schönbrunn Zoo forms a bridge between an imperial past and a technologically connected present.

The zoo’s fortunes have, unsurprisingly, risen and fallen over such a long history. In 1828, a giraffe appeared in Vienna for the first time, sparking a huge interest in all things giraffe-related. The giraffe inspired everything from hairstyles to fashions to a special pastry, the Giraffeln. However, when the unfortunate giraffe died less than a year after it arrived, the craze abruptly ended.

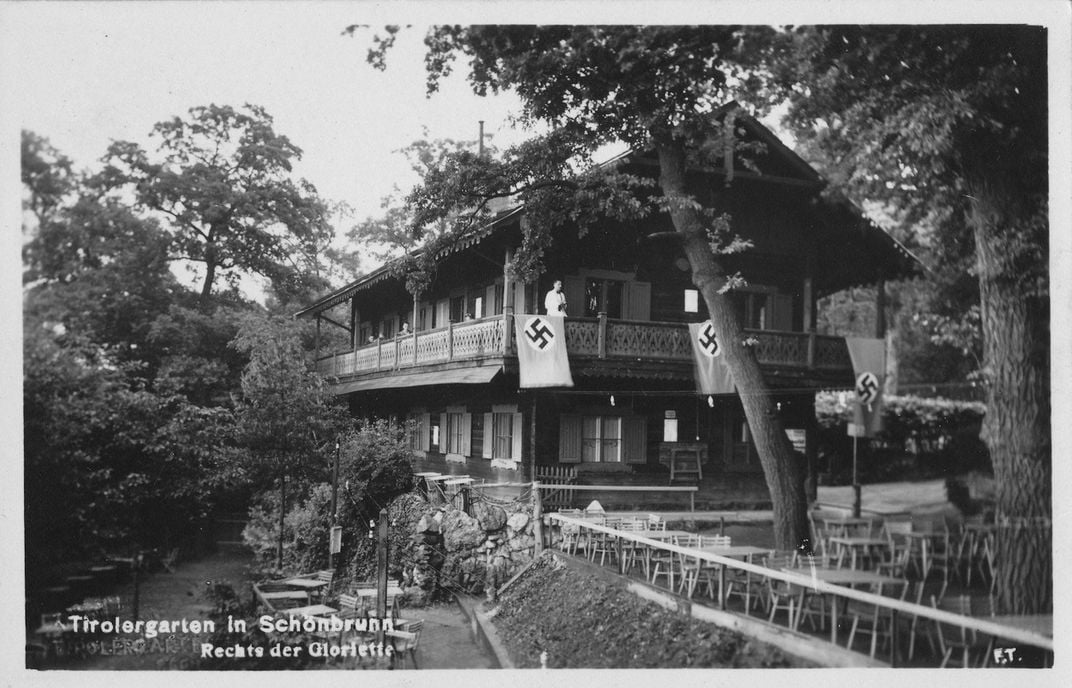

And the zoo was not immune to the nation’s larger historical narrative. The outbreak of World War I ended a period of great growth and modernization, and as many experienced animal keepers were drafted into military service, the zoo suffered. According to Heindl, shortages of food supplies—especially meat for the carnivores—also took a grave toll, forcing the remaining zookeepers to make tough decisions. “Some of the animals were slaughtered and fed to the others,” he says.

The animals weren’t the only ones who endured hardship: Food shortages were rife throughout Central Europe. In 1918, a soldier shot one of the zoo's polar bears to death. According to historian Oliver Lehmann, on his arrest he stated that he shot the bear because “he gets 10 kilograms of meat every day while I have to go hungry.” (Actually, the unlucky bear was subsisting mostly on fish heads.)

In the 1920s, however, the zoo rebounded under the aegis of the impressively named Otto Antonius, a biologist who became the zoo’s managing director. Antonius modernized the zoo’s approach to animal care, focusing on scientific understandings of animal care and emphasizing species protection.

During World War II, the zoo suffered extensive damage from Allied bombing, which resulted in the deaths of many animals, including an elephant and a hippopotamus. By 1945, only 300 animals remained. On the day that Soviet troops arrived, both Antonius and his wife took their own lives. Lehmann writes that Antonius’ suicide note read in part,” I cannot deny overnight something that I honestly believed in … To err is human, and this is something which is now especially apparent.”

Despite the ravages of the war, the zoo lived on. “Schönbrunn Zoo was in a much better position than many German zoos, which were completely destroyed by Allied bombing,” says Heindl. After years of criticism for its languishing facilities, the zoo and the rest of Schönbrunn Palace were designated as a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1996. Over the last 20 years, the zoo has modernized facilities and scaled up its scientific research. Today, roughly 2.2 million visitors journey to the zoo each year, and it is frequently listed as the best zoo in Europe.

Franz Stephan’s cheery yellow pavilion still stands at the center of the park, surrounded by animal enclosures, just as court architect Jean Nicolas Jadot de Ville-Issay intended it in 1759. However, not far away sits the Tiergarten ORANG.erie, a window-lined building holding everything from an orangutan enclosure to a café where visitors can eat apfelstrudel while they watch the apes at play. The zoo that endured will live to see another century.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.