Edward Curtis’ Epic Project to Photograph Native Americans

His 20-volume masterwork was hailed as “the most ambitious enterprise in publishing since the production of the King James Bible”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/2c/6c/2c6cc1e6-5e9d-44b9-98e1-da9706335382/canyon_de_chelly_navajo.jpg)

Year after year, he packed his camera and supplies—everything he’d need for months—and traveled by foot and by horse deep into the Indian territories. At the beginning of the 20th century, Edward S. Curtis worked in the belief that he was in a desperate race against time to document, with film, sound and scholarship, the North American Indian before white expansion and the federal government destroyed what remained of their natives’ way of life. For thirty years, with the backing of men like J. Pierpont Morgan and former president Theodore Roosevelt, but at great expense to his family life and his health, Curtis lived among dozens of native tribes, devoting his life to his calling until he produced a definitive and unparalleled work, The North American Indian. The New York Herald hailed as “the most ambitious enterprise in publishing since the production of the King James Bible.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/40/15/4015afac-66cc-48bf-acc4-4f9f258d7c34/ecurtis.jpg)

Born in Wisconsin in 1868, Edward Sheriff Curtis took to photography at an early age. By age 17, he was an apprentice at a studio in St. Paul, Minnesota, and his life seemed to be taking a familiar course for a young man with a marketable trade, until the Curtis family packed up and moved west, eventually settling in Seattle. There, Curtis married 18-year-old Clara Phillips, purchased his own camera and a share in a local photography studio, and in 1893, the young couple welcomed a son, Harold—the first of their four children.

The young family lived above the thriving Curtis Studio, which attracted society ladies who wanted their portraits taken by the handsome, athletic young man who made them look both glamorous and sophisticated. And it was in Seattle in 1895 where Curtis did his first portrait of a Native American—that of Princess Angeline, the eldest daughter of Chief Sealth of the Duwamish tribe. He paid her a dollar for each pose and noted, “This seemed to please her greatly, and with hands and jargon she indicated that she preferred to spend her time having pictures made than in digging clams.”

Yet it was a chance meeting in 1898 that set Curtis on the path away from his studio and his family. He was photographing Mt. Rainier when he came upon a group of prominent scientists who’d become lost; among the group was the anthropologist George Bird Grinnell, an expert on Native American cultures. Curtis quickly befriended him, and the relationship led to the young photographer’s appointment as official photographer for the Harriman Alaska Expedition of 1899, led by the railroad magnate Edward H. Harriman and including included the naturalist John Muir and the zoologist C. Hart Merriam. For two months, Curtis accompanied two dozen scientists, photographing everything from glaciers to Eskimo settlements. When Grinnell asked him to come on a visit to the Piegan Blackfeet in Montana the following year, Curtis did not hesitate.

It was in Montana, under Grinnell’s tutelage, that Curtis became deeply moved by what he called the “primitive customs and traditions” of the Piegan people, including the “mystifying” Sun Dance he had witnessed. “It was at the start of my concerted effort to learn about the Plains Indians and to photograph their lives,” Curtis wrote, “and I was intensely affected.” When he returned to Seattle, he mounted popular exhibitions of his Native American work, publishing magazine articles and then lecturing across the country. His photographs became known for their sheer beauty. President Theodore Roosevelt commissioned Curtis to photograph his daughter’s wedding and to do some Roosevelt family portraits.

But Curtis was burning to return to the West and seek out more Native Americans to document. He found a photographer to manage his studio in Seattle, but more important, he found a financial backer with the funds for a project of the scale he had in mind. In 1906 he boldly approached J.P. Morgan, who quickly dismissed him with a note that read, “Mr. Curtis, there are many demands on me for financial assistance. I will be unable to help you.” But Curtis persisted, and Morgan was ultimately awed by the photographer’s work. “Mr. Curtis,” Morgan wrote after seeing his images, “I want to see these photographs in books—the most beautiful set of books ever published.”

Morgan agreed to sponsor Curtis, paying out $75,000 over five years in exchange for 25 sets of volumes and 500 original prints. It was enough for Curtis to acquire the necessary equipment and hire interpreters and researchers. With a trail wagon and assistants traveling ahead to arrange visits, Edward Curtis set out on a journey that would see him photograph the most important Native Americans of the time, including Geronimo, Red Cloud, Medicine Crow and Chief Joseph.

The trips were not without peril—impassable roads, disease and mechanical failures; Arctic gales and the stifling heat of the Mohave Desert; encounters with suspicious and “unfriendly warriors.” But Curtis managed to endear himself to the people with whom he stayed. He worked under the premise, he later said, of “We, not you. In other words, I worked with them, not at them.”

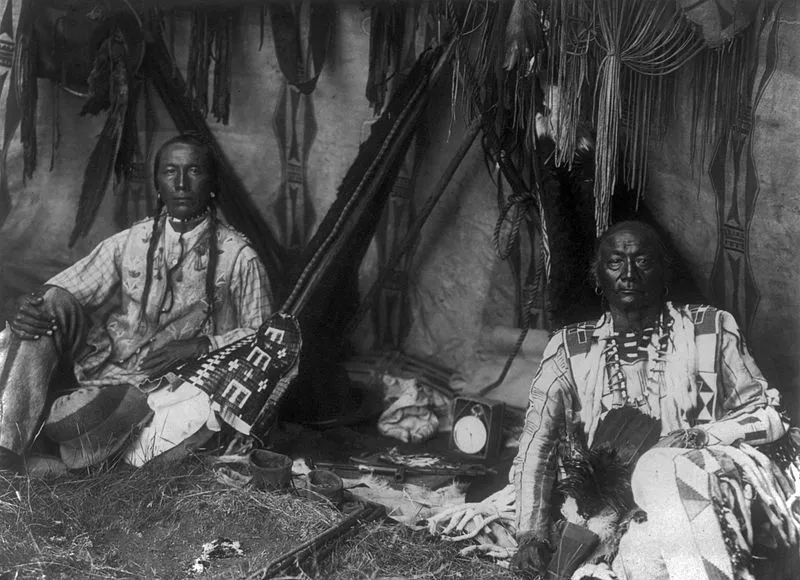

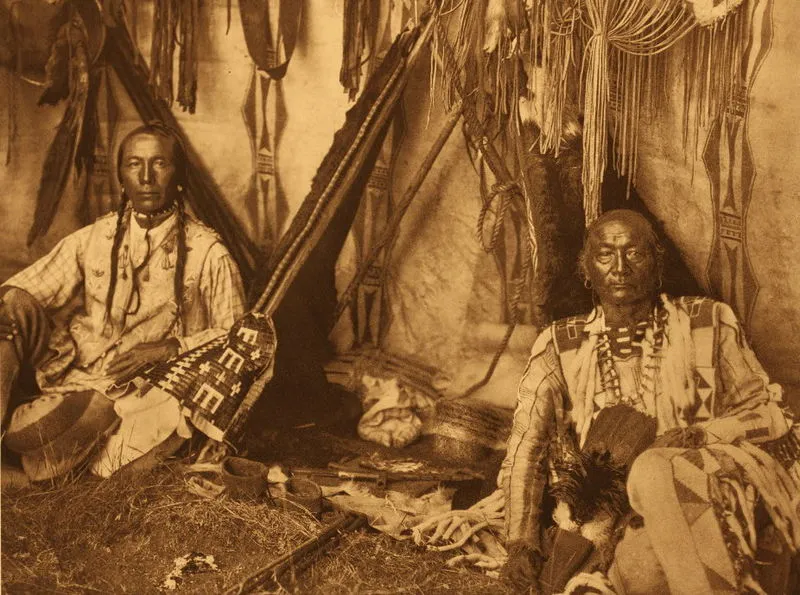

On wax cylinders, his crew collected more than 10,000 recordings of songs, music and speech in more than 80 tribes, most with their own language. To the amusement of tribal elders, and sometimes for a fee, Curtis was given permission to organize reenactments of battles and traditional ceremonies among the Indians, and he documented them with his hulking 14-inch-by-17-inch view camera, which produced glass-plate negatives that yielded the crisp, detailed and gorgeous gold-tone prints he was noted for. The Native Americans came to trust him and ultimately named him “Shadow Catcher,” but Curtis would later note that, given his grueling travel and work, he should have been known as “The Man Who Never Took Time to Play.”

Just as Curtis began to produce volume after volume of The North American Indian, to high acclaim, J.P. Morgan died unexpectedly in Egypt in 1913. J.P. Morgan Jr. contributed to Curtis’s work, but in much smaller sums, and the photographer was forced to abandon his field work for lack of funding. His family life began to suffer—something Curtis tried to rectify on occasion by bringing Clara and their children along on his travels. But when his son, Harold nearly died of typhoid in Montana, his wife vowed never to travel with him again. In 1916, she filed for divorce, and in a bitter settlement was awarded the Curtis family home and the studio. Rather than allow his ex-wife to profit from his Native American work, Edward and his daughter Beth made copies of certain glass plate negatives, then destroyed the originals.

While the onset of World War I coincided with a diminishing interest in Native American culture, Curtis scraped together enough funding in an attempt to strike it big with a motion picture, In the Land of the Head-Hunters, for which he paid Kwakiutl men on Vancouver Island to replicate the appearance of their forefathers by shaving off facial hair and donning wigs and fake nose rings. The film had some critical success but flopped financially, and Curtis lost his $75,000 investment.

He took work in Hollywood, where his friend Cecil B. DeMille hired him for camerawork on films such as The Ten Commandments. Curtis sold the rights to his movie to the American Museum of Natural History for a mere $1,500 and worked out a deal that allowed him to return to his field work—by relinquishing his copyright on the images for The North American Indian to the Morgan Company.

The tribes Curtis visited in the late 1920s, he was alarmed to find, had been decimated by relocation and assimilation. He found it more difficult than ever to create the kinds of photographs he had in the past, and the public had long ceased caring about Native American culture. When he returned to Seattle, his ex-wife had him arrested for failing to pay alimony and child support, and the stock market crash of 1929 made it nearly impossible for him to sell any of his work.

By 1930, Edward Curtis had published, to barely any fanfare, the last of his planned 20-volume set of The North American Indian, after taking more than 40,000 pictures over 30 years. Yet he was ruined, and he suffered a complete mental and physical breakdown, requiring hospitalization in Colorado. The Morgan Company sold 19 complete sets of The North American Indian, along with thousands of prints and copper plates, to Charles Lauriat Books of Boston, Massachusetts for just $1,000 and a percentage of future royalties.

Once Curtis sufficiently recovered his mental health, he tried to write his memoirs, but never saw them published. He died of a heart attack in California in 1952 at the age of 84. A small obituary in the New York Times noted his research “compiling Indian history” under the patronage of J.P. Morgan and closed with the sentence, “Mr. Curtis was also widely known as a photographer.”

The photographs of Edward Curtis represent ideals and imagery designed to create a timeless vision of Native American culture at a time when modern amenities and American expansion had already irrevocably altered the Indian way of life. By the time Curtis had arrived in various tribal territories, the U.S. government had forced Indian children into boarding schools, banned them from speaking in their native tongues, and made them cut their hair. This was not what Curtis chose to document, and he went to great pains to create images of Native Americans posing in traditional clothing they had long since put away, in scenes that were sometimes later retouched by Curtis and his assistants to eliminate any modern artifacts, such as the presence of a clock in his image, In a Piegan Lodge.

Some critics have accused him of photographic fakery—of advancing his career by ignoring the plight and torment of his subjects. Others laud him, noting that he was, according to the Bruce Kapson Gallery, which represents Curtis’s work, “able to convey a dignity, universal humanity and majesty that transcend literally all other work ever done on the subject.” It is estimated that producing The North American Indian today would cost more than $35 million.

“When judged by the standards of his time,” Laurie Lawlor wrote in her book, Shadow Catcher: The Life and Work of Edward S. Curtis, “Curtis was far ahead of his contemporaries in sensitivity, tolerance and openness to Native American cultures and ways of thinking. He sought to observe and understand by going directly into the field.”

Sources

Books: Laurie Lawlor, Shadow Catcher: The Life and Work of Edward S. Curtis, Bison Books, 2005. Mick Gidley, Edward S. Curtis and the North American Indian, Incorporated, Cambridge University Press, 2000.

Articles: “Edward Curtis: Pictorialist and Ethnographic Adventurist,” by Gerald Vizener, Essay based on author’s presentation at an Edward Curtis seminar at the Claremont Graduate University, October 6-7, 2000. http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/award98/ienhtml/essay3.html “Edward Curtis: Shadow Catcher,” by George Horse Capture, American Masters, April 23, 2001. http://www.pbs.org/wnet/americanmasters/episodes/edward-curtis/shadow-catcher/568/ “The Impoerfect Eye of Edward Curtis,” by Pedro Ponce, Humanities, May/June 2000, Volume 21/Number 3. http://www.neh.gov/news/humanities/2000-05/curtis.html “Frontier Photographer Edward S. Curtis,” A Smithsonian Institution Libraries Exhibition. http://www.sil.si.edu/Exhibitions/Curtis/index.htm “Selling the North American Indian: The Work of Edward Curtis,” Created by Valerie Daniels, June 2002, http://xroads.virginia.edu/~ma02/daniels/curtis/promoting.html “Edward S. Curtis and The North American Indian: A detailed chronological biography,” Eric J. Keller/Soulcatcher Studio, http://www.soulcatcherstudio.com/artists/curtis_cron.html “Edward S. Curtis (1868-1952) and The North American Indian,” by Mick Gidley, Essay from The North American Indian, The Vanishing Race: Selections from Edward S. Curtis’ The North American Indian,” (Newton Abbot: David and Charles, 1976 New York: Taplinger, 1977.) http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/award98/ienhtml/essay1.html

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/gilbert-king-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/gilbert-king-240.jpg)