Charlie Papazian, “the Johnny Appleseed of good beer,” as an old friend describes him, “or maybe the Chuck Berry and Muddy Waters and Joey Ramone of beer, overthrowing the status quo,” lives about six miles north of downtown Boulder, Colorado, at the end of a rutted dirt road, in a modest two-story home with views of the Rocky Mountains. He’d fallen in love with the place on sight. The isolated location, the light, the chortling brook in the backyard—perfect. Except for one thing. “You have to understand that I was used to brewing in basements,” he said when I visited him a few months ago. “And this house has no basement! So I had this vision. I’d convert the garage into a single-use facility, the ideal beer-brewing space.”

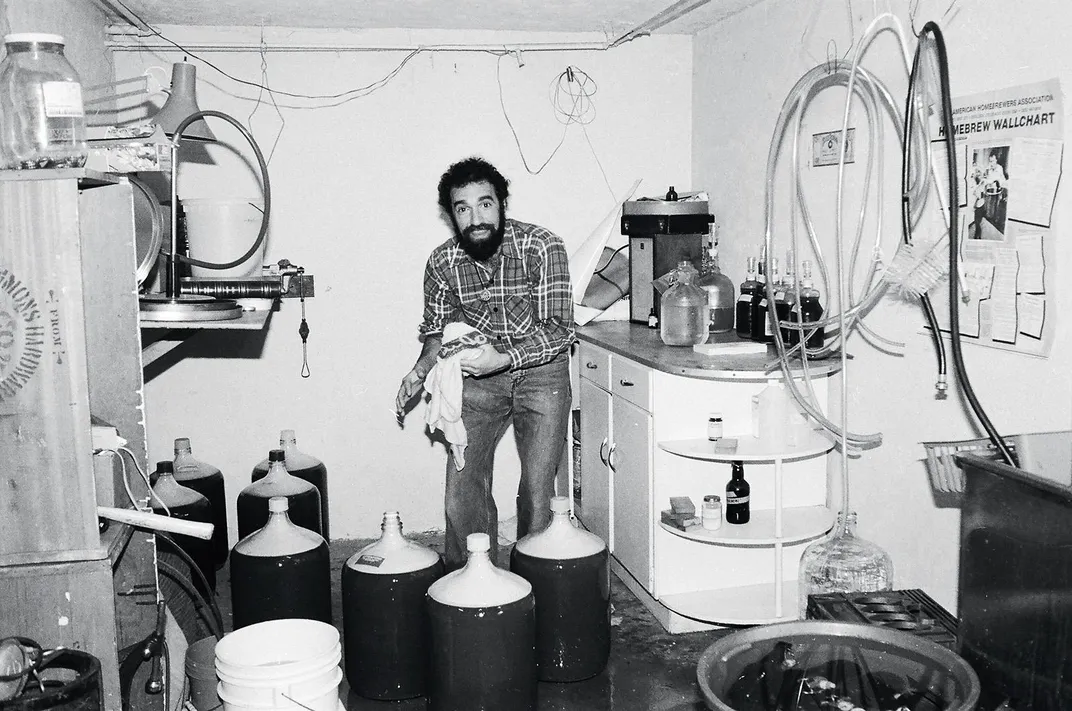

Papazian installed a glass-walled cooler, plus a custom-built, walk-in fridge with six-inch-thick foam-insulated walls he’d reclaimed from a defunct turkey farm. He left the original workbench and a few lockers and added several sets of shelves to stow the essentials: buckets of malted barley, rice, and yeast cultures, glass carboys for fermenting the beer, serpentine coils of tubing and strainers for trapping the errant grain, and a freezer full of hops.

These days, Papazian brews a five-gallon batch of beer about once a month—typically a lager or an ale. More in summer, less in winter. He does not sell it, preferring to dole out samples to friends. “I go to visit a buddy, or I give a talk, and I bring some beer,” he explained. “As a hello, or as a thank-you.” He offered me a pour of a recent concoction: a dark lager made with hops he’d grown in the field behind the garage. It tasted soft; each sip melted on the tongue, like chocolate. “It’s got a porter-like quality to it, doesn’t it?” he asked. “Very drinkable. Smooth and not overly assertive.”

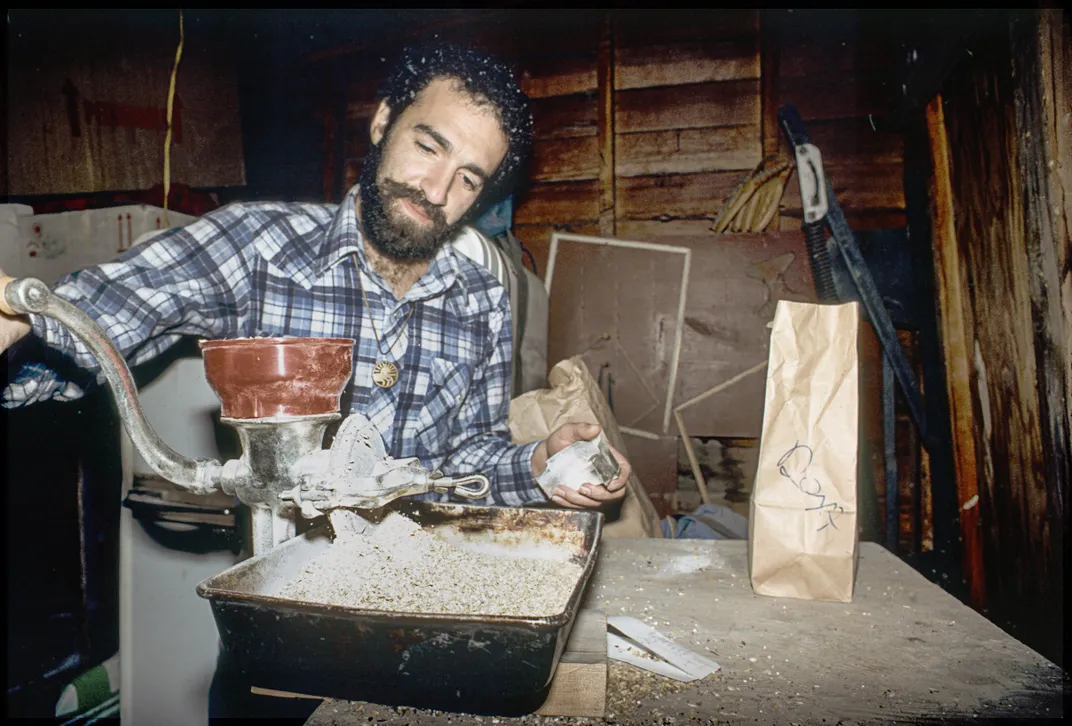

Crossing the garage, he found the barley he’d used for a different batch. He encouraged me to taste a small handful of the grain. “You’ll notice that the longer you chew, the sweeter the barley gets,” he said. “That’s because the enzymes in your mouth are breaking down the starches.” He went on, “Now look, I don’t want to get too Zen-like, but what I’ve always loved about brewing is that you’re dealing with organisms. With biology, with chemistry! With life itself! Take yeast, for example: Depending on temperature, pressure, motion, it gives off different compounds. The beer changes with it.”

I followed him into the walk-in fridge. “These are the collectibles,” he said, dragging his finger over the bottles that lined the shelves. “The cooler out there—that has the beers for drinking. These are the beers for remembering.” He pulled down a few keepsakes. Canned editions from the beginning of his career, when he was still a grade school teacher, homebrewing in his spare time. Some early beers from San Francisco’s Anchor Brewing Company, one of the first microbreweries in the United States. Collectible beers from trips to Denmark, South America, England. A beer he brewed on the occasion of the birth of his daughter, Carla, now 10 years old. He’s saving that one for the day she turns 21 and can enjoy it with him.

I noticed an old poster, a little yellowed with age, hanging above one of the workbenches. “Relax,” it read. “Don’t worry. Have a homebrew.” It was Papazian’s motto. The words had come to him and his fellow homebrewer Charlie Matzen back in the 1970s. The words have since appeared on T-shirts, on bumper stickers and beer caps, and most famously, in Papazian’s beer-making bible, The Complete Joy of Homebrewing, now in its fourth printing. Global sales of the book reportedly exceed 1.3 million copies, but that number, however impressive, doesn’t come close to conveying the book’s vast readership, for dog-eared copies are passed from one generation of beer-makers to the next, an initiation, a rite of passage. Many a successful brewmaster learned the trade from The Complete Joy of Homebrewing. “People still approach me and say, ‘That mantra, it’s changed the way I look at the world,’” Papazian said. “What a gift to be able to hear something like that.”

If he sounded wistful, it was not for nothing. Although he continues to brew beer and to speak at beer events around the globe, Papazian, who is 71, is in the process of slowly withdrawing from the grassroots industry he helped create and sustain over the past four decades. He recently stepped down as head of the Brewers Association, the influential American trade group, and he has officially retired as maestro of the Great American Beer Festival, which he inaugurated in 1982. In an unmistakably valedictory gesture, he donated a battle-scarred old brew spoon, an original homebrewing recipe annotated by hand and a first edition copy of his book to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, where the items are now on display indefinitely. “I think the curators were in awe that I would be willing to give them something so personally valuable,” Papazian joked to me. “I’m just in awe that they wanted it.”

(Try your hand at Papazian's beer recipe inspired by hops grown at the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History)

Jim Koch, the founder of the Boston Beer Company, which makes Samuel Adams, credits Papazian with popularizing craft beer in the United States. Papazian’s retirement represents “the end of an era,” Koch wrote in an email. “It’s hard to imagine a Brewers Association, a Great American Beer Festival or a craft beer industry without Charlie steering the ship. There’s an adage in business that no one is irreplaceable. His departure is going to put that maxim to the test.”

* * *

Today, when many states in the nation are home to 100 breweries and some states count six or eight times that number, it seems almost impossible to imagine that beer was a relatively uniform and even uninspired commodity for most of recent American history. Lagers pale in color and low in alcohol were popular as refreshment but did not engender much connoisseurship or olfactory debate. It was the stuff you slugged back after mowing the lawn on a hot day.

In 1949, the year Papazian was born, the market was almost entirely dominated by big corporations that specialized in largely interchangeable German-style beers: Miller, Pabst, Budweiser, Coors. “I grew up in a mid-century culture, where with food, it was cool to be homogeneous,” Papazian recalled. “You turned on the TV, and it was Velveeta cheese, it was frozen dinners, it was white bread. Wonder Bread! Flavor diversity wasn’t really a thing.”

Papazian was raised in a quiet community called Warren Township, in northern New Jersey. He remembers his upbringing as idyllic. His mother stayed at home with him and his two brothers, and his father, a chemical engineer, managed a manufacturing plant. Occasionally, his parents would buy a six-pack of beer for guests; they kept a liquor cabinet in the living room, but it collected dust. “They weren’t really drinkers,” Papazian told me.

In 1967, Charlie, who was adept with numbers, left for the University of Virginia to study nuclear engineering. He had few longer-term plans. He mulled the possibility of a career in the Navy, but the counterculture appealed to him, too. He grew his wiry brown hair long, played some music, made the pilgrimage to Woodstock. (The ticket stubs and muddy sneakers he wore to the festival are displayed in a vitrine in his home.)

One afternoon in 1970, Papazian was lazing around his Charlottesville apartment, drinking Pabst Blue Ribbon, when a friend mentioned that he’d run into a neighbor, an “old-timer” in his early 70s, who’d learned to brew beer during Prohibition, and was apparently still making it, right there in his basement. “I remember going, ‘Wait, what the heck is homebrew?’ I had no idea such a thing was possible,” Papazian recalled.

A few days later, he paid a visit to the neighbor, who offered Papazian a bottle of a Prohibition-style ale: an unboiled, fermented mixture of malt extract, sugar, bread yeast and water. “It was crystal clear, pale, beautiful-looking, effervescent beer,” Papazian said. “And the taste was cidery, almost. I wouldn’t say it was better or worse than store-bought beer, but it was very different, and that was enough. I was completely fascinated.”

Papazian was working part time as a janitor at a Charlottesville day care facility, which had a kitchen and a capacious basement. “After the kids had gone home, my friends and I, we’d formulate the recipe upstairs,” he said. “You’d open up the malt, put it in a pail, add sugar, add the water, add the yeast, and bring it downstairs and let it ferment. It was pretty basic.”

Several early batches were poured directly down the drain, but Papazian’s skills gradually improved. He learned that dextrose made for better flavor than sugar, and that bread yeast he’d been buying from the supermarket was no replacement for the more refined yeasts on sale at the wine-making supply store. “The beer got good enough that we bottled it up and started handing it out at parties,” Papazian recalled. “People loved it. They were constantly asking, ‘How did you make this?’” In response, he wrote up a two-page instructional manual. “It never occurred to me to keep it to myself,” he went on. “I was all about sharing it as widely as I could.”

After college, while traveling with a friend to Wyoming, Papazian passed through Boulder, then as now a college town with a healthy population of hippies and a growing tech sector. Papazian decided to stay. “I spent about a month crashing on a friend’s floor, applying for jobs,” he told me. He landed one as a janitor, and another at a shoe manufacturing plant; he quit them both. Then a friend told him that the private elementary school where she worked was looking for a new teacher. “My degree was in engineering. I had no teaching certification. But I went in, and the boss said, ‘Hang out for a day and see if you like it.’” He stayed for ten years.

Papazian had left his brewing equipment back in Charlottesville, assuming his beer-making days were behind him, but his friends knew about his talent, and they wanted lessons. “I remember going, ‘All right, fine, give me the money, and I’ll go get the trash pail at Kmart, and I’ll get the yeast at the supermarket,’” Papazian recalled.

He offered classes, once a week, in his kitchen. There were always more students than spots. “You had attorneys, airline pilots, other teachers, but also people who were just hanging out. Musicians, outdoors-types,” he told me. “A real mix.” Among his earliest students was Jeff Lebesch, who would go on to co-found New Belgium Brewing, in Fort Collins, Colorado, purveyors of Fat Tire Amber Ale, as well as Russell Scherer, who became the original brewmaster at Wynkoop, a Denver brewery co-founded by John Hickenlooper, the former governor of Colorado.

Together with his students, Papazian began experimenting with flavors and ingredients. “The spice cabinet in that kitchen was right above the stove, and every once in a while, we’d open it, and say, ‘Let’s put some cinnamon in there, some allspice,’” Papazian told me. “We messed around with tea, honey, fruit.” In retrospect, he was pushing the limits of an age-old art and science—redefining beer itself.

* * *

One afternoon, Papazian and I arranged to share a couple of pints in the taproom of his local brewpub, Avery Brewing Company, which occupies a series of low industrial buildings in Boulder, nor far from his home. As we walked through Avery’s front doors, a roar went up—“Charlie!”—and the staff assembled themselves in a reception line, proffering hands and clapping Papazian’s shoulders. We found a seat. Papazian studied the menu. There was nary a pilsner to be found. Instead, there was an assortment of India Pale Ales, promising varying levels of alcohol and varieties of hops; a persimmon-and-wheat ale; a hazelnut, toffee and mocha-flavored ale called “Old Jubilation”; a “PB&J stout,” brewed with raspberries and peanuts and aged in bourbon barrels. Papazian looked amused. “To see the way the palate of the American beer drinker has evolved,” he said, “well, it’s really something, isn’t it?”

I asked if back in the 1970s he could have imagined walking into a brewery and ordering a peanut-butter-and-jelly-flavored stout. He shook his head. “It’s difficult to stress how different things were—at every level,” he said.

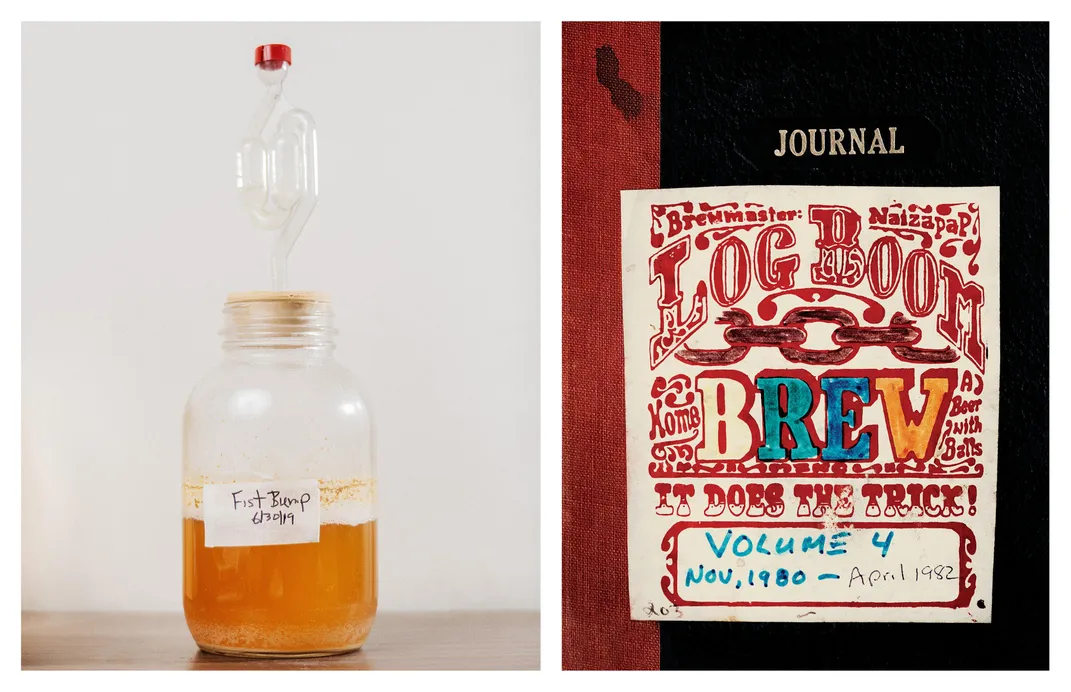

Back then, brewing beer at home wasn’t even legal, and selling or distributing homebrew was an offense punishable by hefty fines. But in October 1978, President Jimmy Carter legalized homebrewing nationwide. In December of that year, Papazian and Charlie Matzen, a friend and former student, published the debut issue of Zymurgy, a beer-making magazine named for the science of fermenting yeast for beer or wine. Inside were recipes, comics, columns and reported pieces; one dispatch in the first issue covered the beer-making scene in Hawaii.

“What we did was go down to the Boulder Public Library,” Papazian said, “and go through the Yellow Pages for different major cities, looking for beer-making supply stores, and we’d mail out sample copies.” As part of the $4 subscription price, Zymurgy promised membership in a brand-new organization, the American Homebrewers Association. “We knew there were all these homebrewers out there, and we knew how passionate they were. The AHA was our attempt at connecting everyone, at bringing them together as a community.”

Membership requests rolled in. Some were sent by individuals, others by informal clubs, including the Homebrew Computer Club, a group founded by Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak, and the Maltose Falcons, an organization generally considered the first of its kind in the United States. In 1981, Papazian traveled to England to serve as a judge at the Great British Beer Festival. “I thought, ‘This idea of celebrating national beer culture—I love it.’” Surely, the concept was exportable.

For the first Great American Beer Festival, held in 1982 in a conference room at Boulder’s Harvest House Hotel, Papazian secured the participation of a handful of small breweries, including Anchor Brewing from San Francisco and Sierra Nevada, from Chico, California, which had just begun selling its now-famous Pale Ale, widely credited with bringing piney, citrus-flavored hops to the forefront of American beer-making in the decades to come. Behemoths such as Coors were invited to participate, but only if they brought beers that “were special enough, and reflected some kind of culture,” as Papazian put it.

Less than two years later, Papazian published The Complete Joy of Homebrewing. “So now you’ve decided to brew your own beer,” he wrote in the introduction. “In essence, you’ve given yourself the opportunity to make the kind of beer that you like. Reading this book and learning the fundamentals will give you a foundation to express yourself unendingly in what you brew. Remember, the best beer in the world is the one you brewed.”

The book rocketed off shelves. Craft beer supply stores couldn’t keep it in stock. Papazian quickly became a cult figure, the leader of a movement. “You know when you were a kid, and you were on this journey to find great music, and then someone slipped you an eight-track, or a cassette, and it changed your world?” Marty Jones, a longtime Colorado beer world promoter and enthusiast, asked me. “For people who loved beer, it was like that with Charlie and The Complete Joy of Homebrewing.”

Papazian hired a marketing director, an accountant, some office staff. Just a few years earlier, there were five or so microbreweries in the United States; within a dozen years, there were close to 200. “We now have more than 8,000 breweries in the United States,” Theresa McCulla, curator of the American Brewing History Initiative at the National Museum of American History, told me. “But these small professional breweries are almost entirely founded by people who began as homebrewers. To think about craft beer, you really have to understand how homebrewing became so popular, and continues to stay so popular as a social phenomenon and a hobby that so many Americans enjoy.”

By 2002, the Great American Beer Festival—a multi-day extravaganza and proving ground for upstart breweries—had moved to the Colorado Convention Center, in downtown Denver, and attendees could sample more than 1,800 beers. In 2019, the year of Papazian’s retirement, attendance exceeded 60,000. Four thousand beers from 2,300 breweries were on tap; every state in the country and the District of Columbia were represented. The awards were split into more than 100 categories—from mainstays like Pilsner and Brown Porter and Cream Stout to contemporary powerhouses like Juicy or Hazy Imperial India Pale Ale and American-Style Sour Ale to kookier offerings like Chili Beer (brewed with hot peppers) and Mixed-Culture Brett Beer (Brett, short for Brettanomyces, or British fungus, is a type of wild yeast).

To peruse the list of winners over the decades is to observe American beer, which originated with recipes borrowed from Germany and the British Isles, come fully into its own. “It used to be Europe that drove what was in style,” a veteran of Colorado’s beer industry told me. “Now it’s American brewers who have the creativity, who start trends that pop up elsewhere. The festival, and Charlie, are the biggest parts of that transformation.”

* * *

On a bright December day Papazian and I made a trip to downtown Denver, to visit Wynkoop Brewing Company, Colorado’s first brewpub, which was founded in the late ’80s. The operation spills over several floors, with big windows that allow guests to watch the beer being made; a picture of Papazian, an early supporter and a close friend of Hickenlooper’s, hangs on the wall.

Papazian had not called ahead, and at the hostess stand he ducked shyly to avoid detection, but he was spotted anyway, and soon the brewmaster was looming over our table. He looked at me and cocked a thumb toward Papazian. “This is the legend right here,” he said. “The real OG.”

Papazian opened the menu and selected a pint of Rail Yard, a mild amber ale brewed with Tettnanger and Fuggle hops.

We left Wynkoop and drove a mile and a half to the History Colorado Center, a Denver museum, which last spring opened an exhibition entitled “Beer Here! Brewing the New West.” The organizers, Jason Hanson and Sam Bock, are beer lovers and occasional homebrewers.

We climbed the stairs to the second floor and wended through the start of the exhibition, with its old saloon furniture and antique bottles and paintings of Colorado’s first industrial breweries. Next came the Prohibition years, when rogue beermakers and distillers were chased by pistol-wielding cops. Then came the rise of mass-market beer, the proliferation of the aluminum can, and old television advertisements for Coors, with their gauzy footage of snow-painted peaks. “Here’s a crazy fact,” Hanson said. “In 1975 Coors was the only brewery in Colorado.” (The state is now home to more than 400.)

We turned the corner and stepped into the kitchen of Papazian’s first Boulder home—the room where he taught his first classes, and where Zymurgy and the AHA were born. Hanson said, “We wanted the flow of the exhibition to go from Coors to Charlie’s kitchen, because the craft scene really grew out of a reaction to mass-produced beer, right?”

“The moment,” Bock added, “Americans decided not to just accept beer they didn’t like.”

The museum staff had based the reproduction on old photographs Papazian had provided them. Everything was period-accurate, from the vintage stovetop to the Kit-Cat Klocks with their beady eyes and swinging tails.

“They got it exactly right,” Papazian said. He ran his hand lovingly over the replica brew pails, the glass carboy, the long-handled wooden spoon.

“Don’t forget about that,” Hanson said, tapping a sticker on the front of the fridge.

Smiling, Papazian read the words aloud: “Relax. Don’t worry. Have a homebrew.”

Beer Is Not Just a Drink

It's a cultural boom. And a Smithsonian scholar is on the case

— by Arik Gabbai

When she was hired three years ago to serve as curator of the Smithsonian’s American Brewing History Initiative, Washingtonian magazine called her position the “Best Job Ever.” For the first six months, though, Theresa McCulla spat out every beer she tasted—she was pregnant.

Since then she has made 30-odd research trips, sipping, documenting, collecting and interviewing. Among the brewers, maltsters and product designers she has tapped for oral histories are pioneers such as Charlie Papazian (“one of the more substantial and rewarding relationships I’ve established during my time at the museum,” she says) and Annie Johnson, the first African-American awarded Homebrewer of the Year (2013), who has worked with a Seattle company that manufactures semi-automated homebrewing equipment aimed in part at people with disabilities.

Traveling to Random Lake, Wisconsin, McCulla met with woodworkers who design and produce 80 percent of America’s barroom tap handles. “Tap handles are often the first line of communication between a beer drinker and a brewer,” says McCulla, who has a doctorate in American studies from Harvard and a knack for finding cultural history in seemingly unremarkable objects. She has collected early annotated homebrewing recipes, beer labels from former upstarts like Sierra Nevada, even the vibrating tabletop football game that Sam Calagione, founder of Dogfish Head, bought at a thrift store and retrofitted to shake hops into his boil kettle, thus inventing “continual hopping” and becoming a demigod to hop-heads nationwide.

“America has the most creative and dynamic small brewing industry in the world,” McCulla says. Curiously, many of the most important American innovators weren’t initially focused on business. “Microbrewing and craft brewing grew out of grass-roots movements like do-it-yourself culture and the counterculture. These brewers defined themselves as united in a struggle to make beers that were individualistic, and they created a new wave of small businesses, often with quirky personalities, that emphasized causes like environmental sustainability and community engagement.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4a/95/4a95233e-3326-4104-a34e-53b2d0e5e5ef/mobileopenerjun2020_g10_homebrewing_copy.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/63/b0/63b034ff-8d30-4399-9b62-bcb087439005/openerjun2020_g10_homebrewing.jpg)