The East Coast May Be On the Brink of a Hop Renaissance

Can a farmer and a brewer come together to bring hops back to the eastern United States?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/cf/0a/cf0a7b78-114d-40b4-9441-84cf5e86b8d1/east_coast_hop_3.jpg)

For years, whenever anyone asked Bryan Butler, a scientist with the University of Maryland’s School of Agriculture and Natural Resources, why the school wasn’t doing work with hops, one of the elemental ingredients for brewing beer, he would give the same short, simple answer: “You can’t grow hops in Maryland.”

It’s not so much that one absolutely can’t grow hops in Maryland, or on the East Coast more generally. In the era before Prohibition, Maryland was home to a thriving brewing industry, with over 100 breweries reportedly located in Baltimore alone. Farmers across the mid-Atlantic grew hops for beer—in Maryland, they grew enough to supply 10 percent of the hops used by brewers in the state. Today, there are still a handful of farmers who continue that tradition. But hops—one-third of the brewer’s trinity, along with grain and yeast—are a temperamental crop, better suited to the drier, more stable climate of the West. Today, more than 75 percent of the hops grown in the United States are grown in a small slice of eastern Washington known as the Yakima Valley, and these are the hops that have grown to dominate the commercial—and craft—beer industry.

Hops—the flower of the herbaceous climbing plant Humulus lupulus—have been cultivated for centuries by farmers looking to add flavor to beer; the first recorded use of hops as a flavorant comes from 8th century Benedictine monks in Germany, who grew the plant in their herb gardens. But, as far as crops go, hops are a fickle sort. They require long days and short nights during the growing season, and require a few months of cold temperatures—40 degrees Fahrenheit or colder—for a few months before forming cones, meaning that they realistically only grow particularly well in a small area of the United States, between 40 degrees and 50 degrees latitude. Hops are also prone to pest and disease pressure, especially Hop Powdery Mildew (HPM), a serious fungal disease.

But Butler is an agricultural scientist—so when Flying Dog, a craft brewery based in Frederick, Maryland, came to him with a chance to find out once and for all whether hops can flourish in the variable climate of the mid-Atlantic, where temperature and precipitation can swing wildly from week to week, he approached the project with a mentality that was both open-minded and deeply logical. For centuries, hops had been grown primarily in Europe. But in recent years, the craft beer boom in the United States has encouraged domestic hop growers to push the boundaries of what is possible when it comes to hop production, and Butler wanted to see once and for all if Maryland could be a part of a new, distinctly American kind of brewing tradition.

“If this fails and doesn’t work, that’s okay,” Butler said. “But we’ll prove it one way or another through research-based information.”

Though the East Coast Hop Project—the formal name of the joint endeavor between the brewers at Flying Dog and the University of Maryland’s scientists—officially launched in the summer of 2017, the provenance of the project goes back to 2012, when the Maryland state legislature passed a bill allowing farms that grew ingredients for beer—either grain, hops or some other component like fruit—to brew and sell that beer to customers. The bill was championed by local lawyer-turned-farmer Tom Barse, who had a large plot of hops growing on his farm and wanted to combine his career of farming with his love of beer. And Barse wasn’t alone in that desire—by 2015, ten separate farms had applied for the designation of farm brewery.

As Barse was pushing for farmers and brewers to come together legally, Ben Clark, a brewmaster with Flying Dog, saw business potential in bringing the two professions under one roof. A lot of people drink beer, but few other than brewers know the exact specifications needed to make hops, yeast, grain and water merge into the perfect drink. It is, in a way, the same with farmers—as farms become bigger and more centralized, fewer and fewer people understand the kind of work that goes into to making something grow from the earth. So Clark found a cohort of interested, local hop farmers, including Barse, and brought them together to swap stories at Flying Dog. The result was a kind of hop market, where local farmers would bring their wares to the brewery for local brewers.

Almost immediately, Clark identified a major problem with the local hops: there was no quality control, and farmers would bring freshly harvested, wet hops to the brewery in garbage bags, only to see the hops go bad a few days later. Moreover, normally when hops are added to the beer—either early on during the brewing process to add bitterness or towards the end to add aroma—they are pelletized, meaning they are ground into a powder and pressed into something more closely resembling rabbit food than a conical hop flower. But the Maryland hop farmers were so new to the crop that they had no idea how to pelletize hops, so they would bring in the whole hops, which decay more quickly and can be more inconsistent for brewers than pelletized hops.

Still, Clark was committed to the idea that Maryland brewers have an available supply of local hops, should they want them. The issue, it seemed, was that the crop was too new and any institutional knowledge from the Prohibition-era had long since vanished. What the Maryland farmers needed, Clark realized, was someone to help them identify the best practices for growing, and harvesting, hops in Maryland.

Luckily for Clark, Barse, who graduated from the University of Maryland in 1977, knew someone who might be able to help: his fellow Terrapin, Bryan Butler, who, largely at Barse’s own prodding, had been toying around with the idea of growing hops on the university’s 500-acre facility in Keedysville, just outside of Antietam Battlefield.

So Barse, a little bit hop farmer and a little bit brewer, introduced his friend at Flying Dog to his friend at the University of Maryland. To them, it felt like a meeting of the minds—a partnership that could explore both how to grow hops in Maryland, and how to brew them.

“We need a quality product at a favorable price, from a market standpoint, that is like what we’re seeing on the West Coast,” Clark said. “And [Butler] is working from the other side of it, trying to see if that is even possible on the East Coast.”

Hops’ sensitivity to climate—particularly heat and humidity—explains why it thrives mainly in the arid heat of the eastern Pacific Northwest, and why the majority of the most popular hops were bred for the West Coast at the two primary land-grant universities in the Pacific Northwest, Oregon State University in Corvallis, Oregon and Washington State University in Pullman, 200 miles east from the Yakima Valley. Many of the varieties of hops most heavily associated with craft beer in general and IPAs take their name from that place of origin, like Cascade, the hop used in the original craft IPA brewed by San Francisco-based Anchor Steam in the 1970s.

But just because a crop or variety of crop is particularly well suited to a specific region doesn’t mean that it can’t grow elsewhere—it just requires a kind of local, agricultural knowledge. To help rebuild that knowledge, Butler dedicated a plot of land at the university’s Western Maryland Research & Education Center to hops, planting 12 varieties in 2016 and another dozen in 2017. The hops were a mix of popular West Coast and New Zealand varieties, as well as a handful of varieties that were already being grown by local farmers. Butler and his team of researchers collected data on fertility, irrigation, disease, pest management, harvest timing, and unique levels of acids and oils in each hop.

Then, with the help of brewers from Flying Dog, they pelletized those hops and sent them—along with the data Butler’s team had collected—to the brewery. From there, it was up to the brewers at Flying Dog to experiment with how the various varieties reacted when added to beer. It wouldn’t suffice to simply find a variety that grew well in the Maryland soil—it also had to taste good. The most famous West Coast hops are often associated with flavors of pine or citrus, and add bitter elements to brews like IPAs. But hops can also add flavors of grass, flowers or spice.

“We had a hop—Canadian Red Vine—that produced the equivalent of 900 dry pounds per acre, on a one year old plant. Fantastic yield, easy to grow, easy to harvest, did great,” Butler explained. But when the brewers sensory tested those hops, creating what’s known as a “hop tea” by steeping the hops in a small batch of light lager (think Miller Light or some equivalent), the brewers noted with some disappointment that the taste was akin to freezer-burned strawberries.

“So here’s this great producer, and it really wasn’t any good,” Butler said. “From a horticultural perspective, I would say ‘grow this.’ But when they really get down to brewing beer, maybe not so much.”

Not all varieties yielded similar disappointing results. Flying Dog’s Clark recalls one variety—a little-used hop known as Vojvodina that typically imparts woodsy notes of cedar and tobacco—that, when added to a hop tea, presented flavors of mint and melon. Another hop, typically grown in the Southern Hemisphere and used largely as a bittering agent, presented big, fruit flavors more like traditional West Coast hops.

Those subtle deviations in taste from what brewers expected led Clark to speculate, as others have more broadly, that the hops acted like wine grapes, where the terroir, the unique climate and soil of its geographic location, affects the flavor profile.

But there are reasons beyond taste that a variety of hop could prove uniquely suited to the East Coast, like finding a variety that might be more pest-resistant or produce better yields in the Maryland climate than out West. For now, Butler plans to find those varieties the old-fashioned way, either by testing an already-known strain at the University’s test farm or by manually crossing different strains of hops to see if he can find a winner—though improvements in gene editing could someday help speed the process along.

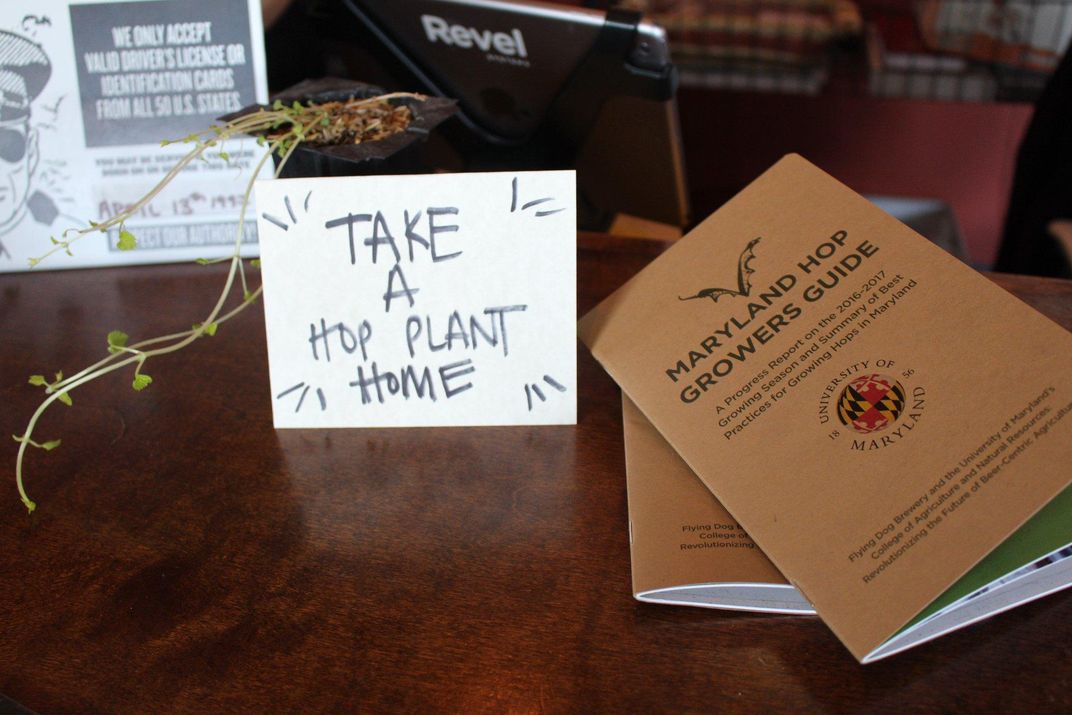

Using the hops delivered by Butler, the brewers at Flying Dog pared the group of 24 down to their four favorites, and debuted a beer called “Field Notes” in March at the brewery’s tasting room. It’s the first commercially available beer brewed with hops grown at the University of Maryland farm. The project also released three beers—each brewed with locally grown hops from either Maryland or New York—in mid-April. Clark explained that by using hops from a farm in New York, and not just Maryland, the newly released beers offer a fuller picture of what hop production can mean for the mid-Atlantic as a region.

Ultimately, the project, which has funding from both Flying Dog and the university to continue for at least the next three years, isn’t about answering the question of if hops can grow along the East Coast, but whether they can grow well enough—or brew well enough—to compete with hop farms out West. For now, Butler and Clark agree that it will ultimately boil down to whether consumers are willing to pay a premium for beer grown with local hops. East Coast hop farmers, they explain, don’t have the economy of scale as out West, and will likely have to pay more for pest control and disease management—something that’s likely to continue unless the project can identify a variety of hop that thrives in the volatile East coast climate.

“When you add all those things together, it really makes it feel like a not very economically viable project,” Butler said. But for all the data he can collect on hop fertility and irrigation needs, there’s one factor for which he can’t account: taste. If Butler and Clark can figure out how to provide customers with a consistent product, they say, it’s possible that buyers will place a premium on locally-grown hops with a strong connection to the region—as has happened in many places across the country with local produce.

“If the market says this is something it wants and if people are willing to pay and we can replicate the process, it might be able to work,” he said. “It’s really going to be price, quality, quantity, and consistency. That’s what we need to achieve, so that we can be like the West Coast.”