How Guinness Became an African Favorite

The stout’s success stems from a long history of colonial export and locally driven marketing campaigns

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7a/23/7a239d25-94a9-49d9-adee-856cf102edb1/5504735567_cc1958c666_b.jpg)

As revelers from Chicago to Dublin celebrate St. Patrick’s Day, they’re sure to be filling up on Guinness, Ireland's hallmark brew. In the United States and elsewhere, Guinness is synonymous with Irish tradition and St. Patrick's Day celebrations. But, there’s one continent where Guinness has absolutely nothing to do with wearing green or hunting down leprechauns at the end of rainbows: Africa.

Most Africans don’t celebrate St. Patrick’s Day, but they still love their Guinness. The dark brew makes up about 45 percent of beer sold by Diageo, the company that owns Guinness, on the continent, and Diageo is one of four companies that split about 90 percent of the African beer market. Popularity varies from country to country, and Guinness is a particular favorite in Nigeria.

As opposed to the standard Guinness draught that you might order at the local pub or the Guinness Extra Stout you might pick up at the grocery store, the vast majority of Guinness consumed in Africa is called Foreign Extra Stout. It's essentially the same beer that Guinness began exporting to the far reaches of the British Empire in the 18th century.

In his book Guinness: The 250 Year Quest for the Perfect Pint, historian Bill Yenne discussed the popularity of Guinness abroad with brewmaster Fergal Murray, who worked at the Guinness brewery in Nigeria in the 1980s. “I’ve talked to Nigerians who think of Guinness as their national beer,” Murray recalled. “They wonder why Guinness is sold in Ireland. You can talk to Nigerians in Lagos who will tell you as many stories about their perfect pint as an Irishman will. They’ll tell about how they’ve had the perfect bottle of foreign extra stout at a particular bar on their way home from work.”

Africa now rivals the UK in their stout consumption. In 2004, Guinness sales in Africa beat those in the United Kingdom and Ireland, making up about 35% of the global take. In 2007, Africa surpassed Ireland as the second largest market for Guinness worldwide, behind the United Kingdom, and sales have only climbed since then (by about 13 percent each year).

The story of Guinness in Africa begins in Dublin. When Arthur Guinness II took the reins of his father’s brewery in 1803, he gradually expanded their exports – first to England, and then abroad to Barbados, Trinidad, and the British Colony of Sierra Leone. Originally dubbed the West Indies Porter, Guinness Foreign Extra Stout was first brewed in Dublin in 1801 and arrived in West Africa in 1827. Where the British Empire established colonies or stationed soldiers, Guinness shipped their beer. By the 1860s, distribution reached South Africa as well. Like Coke in its globalization of soda, Guinness developed partnerships with local breweries, who bottled the beer.

As many indigenous populations began to overthrow their colonial rulers and the British Empire began to crumble, Guinness remained. In 1960, Nigeria gained its independence from the UK, and two years later, the Nigerian capital of Lagos became home to the first Guinness brewery outside of the United Kingdom. (Technically, a brewery opened by Guinness in New York in 1936 was their first foreign effort, but it closed in 1954.) Success in Nigeria spurred the building of another brewery in nearby Cameroon in 1970. Today, 13 breweries produce Guinness in Africa.

The Guinness Extra Foreign Stout consumed in an African bar is a bit different. Instead of barley, it’s typically brewed with maize or sorghum, which produces a more bitter taste compared to barley. African farmers have a long tradition of brewing the grain, so the product is well suited to the African palate. At 7.5 percent alcohol by volume, it also boasts higher alcohol content compared to the roughly 4-5 percent found in Guinness draught and Guinness Extra Stout. That's a relic of efforts to preserve the beer while it traveled to foreign ports. But, the flavor is essentially the same: since the 1960s, overseas brewers have added a flavor extract, a “concentrated essence” brewed in Ireland, so that no matter where you ordered a Guinness it would stay true to the original Dublin flavor.

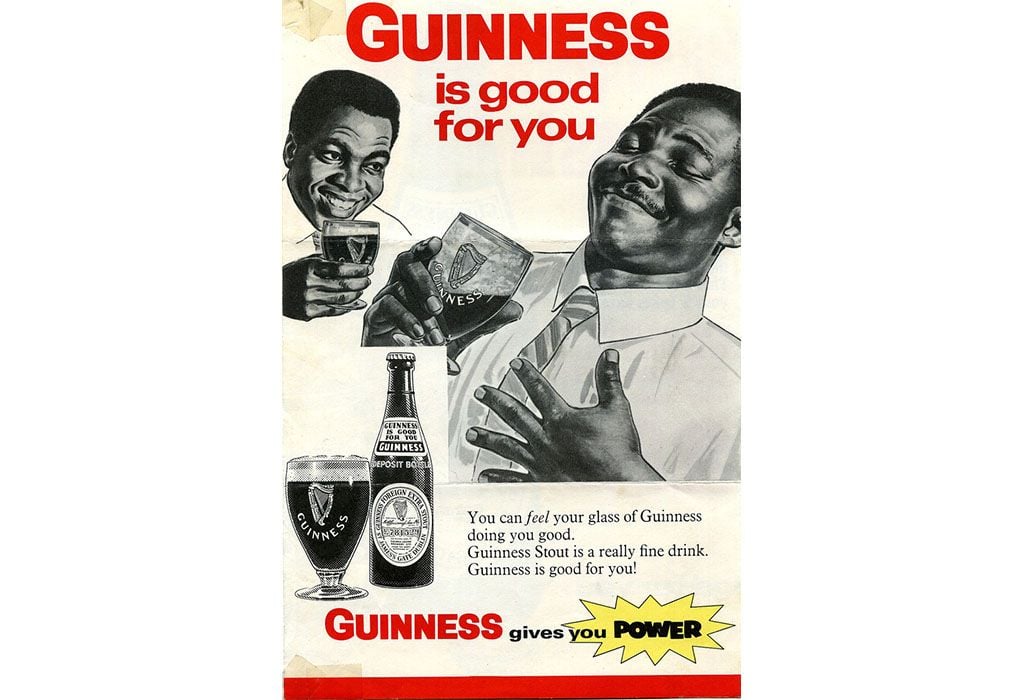

Advertising campaigns in the 1960s introduced one of the beer’s ad slogans: "Guinness gives you power"— a variation on a contemporary European ad slogan, "Guinness for Strength," evoking the idea that tough, masculine men drink the stout after a hard day's work. In the last decade Guinness revisited the old slogan with a hugely successful marketing campaign across Africa that cast a young, strong journalist character named Michael Power as a sort of African "James Bond." At the end of a television or radio adventure, Power saved the day and uttered the same catchphrase: “Guinness brings out the power in you!” In 2003, Guinness took things a step further, launching a feature film called Critical Assignment with Power as the hero and plotline of political corruptiona and clean water issues (here's the film's trailer). It was filmed in six different African countries and released in theaters across Africa and in the U.K.

Two things made the Michael Power campaign hugely successful. First, it played into cultural ideals of a strong African male—not unlike hypermasculine ads employed in Ireland, the U.K., and elsewhere by Guinness and other beer brewers. Promoting the idea that tough guys drink whatever beer you're selling is hardly revolutionary. However, Power lacked ethnic affiliation, so he could appeal to everybody regardless of ethnic or tribal group. This African “James Bond” was both universally appealing and the guy one could aspire to be. Michael Power was phased out in 2006. Guinness has continued to play on similar themes, associating their stout with the concepts of "greatness" in all men and being "more than" on billboards across the continent, with steady success.

This year the beer made headlines with a new ad that taps into its African roots and highlights sapeurs, a group of well-dressed men in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Formally known as the Société des Ambianceurs et des Personnes Élégantes, sapeurs come from all walks of life and evoke the elegant fashions of Paris.

The ad has drawn praise for its positive portrayal of Africans and criticism for its failure to clearly connect the brand with the culture, but interestingly it’s not aimed at an African audience. At least for now, it’s used in European marketing. But, as MIT media scholar Ethan Zuckerman notes on his blog, the ad “could easily run on the continent, and features a form of actual African superheroes, not an imaginary one.”

Whether audiences across Africa would embrace them, remains to be seen. But, either way, Guinness seems to be embracing its African connections.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2014-01-27_at_12.05.16_PM.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2014-01-27_at_12.05.16_PM.png)