Port Uncorked

The sweet wine rejuvenates its image

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/port_631.jpg)

Port, Portugal's famous fortified wine, is undergoing a personality change, shedding its snobbish image and defending its turf.

The sweet wine from the rugged, steep terrain around the Douro River in northern Portugal, widely regarded as the world's first protected wine region, is renown not only for its full body (it's about 20 percent alcohol) but also for being the darling of the British establishment, the drink of "old boys" and aristocrats. Admiral Lord Nelson is said to have dipped a finger in his glass of port to draw a map of his battle tactics for the Battle of Trafalgar. "Port is not for the very young, the vain and the active," wrote British author Evelyn Waugh. "It is the comfort of age and the companion of the scholar and the philosopher."

This image of being old fashioned in addition to increased competition from newer wine industries in California and Australia have been a double whammy for port's producers, several of them British, and for Portugal—where port accounts for 80 percent of all wine export revenue.

But recently the venerable, centuries-old wine has been fighting back to protect its famous appellation. In 2005, port makers helped found the Center for Wine Origins, a Washington. D.C.-based organization charged with educating the public about "the importance of location to winemaking." Thirteen wine regions, including Champagne, Napa and Chablis now belong to the group. These ownership efforts received a real boost last December when the European Union and the United States signed an agreement specifying that no new American fortified wine can be labeled "port," although those already on the market can continue to use the name.

While guarding its territory, port has been courting a trendier crowd—young professionals, male and female, who might try a glass or two at a restaurant, enjoy it with dark-chocolate mousse, even sip it on the rocks.

"Many younger wine drinkers don't have port on their radar screen," says George T. D. Sandeman, president of the Association of Port Wine Companies, the seventh generation in his family involved in the business. "We have to stop telling consumers that they have to age vintage port for 24 years and then drink it in 24 hours."

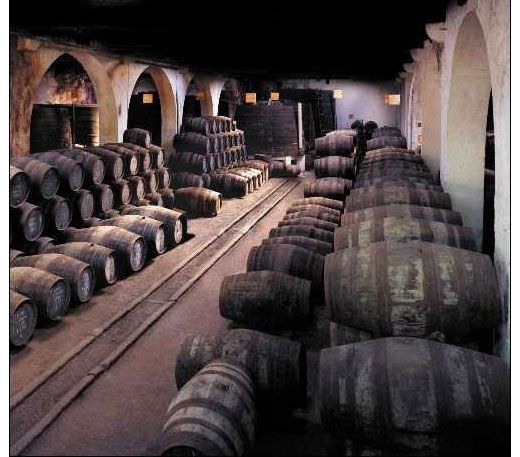

For centuries, that has been the mantra for enjoying the finest port, called "vintage." Forty-eight grape varieties can go into port. White ports blend white grapes and are often sweet; ruby ports, always sweet, blend red grapes; tawny ports, which are aged in wood barrels and come either blended or unblended, get their name from their amber color; and harvest ports, which are from a single harvest and aged at least seven years.

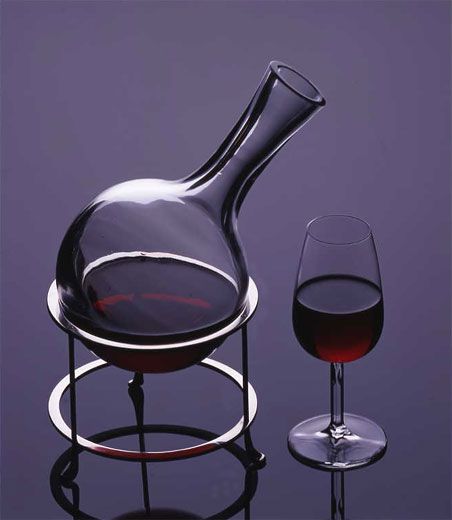

Vintage port, the jewel in the crown, is made up of a single harvest declared by a producer as the very best under the rigorous standards set by Portugal's Port Wine Institute. Aged in the bottle between 10 and 20 years after being kept in barrels for no more than two and a half years, vintage port becomes better with age and is drinkable for decades. However, it is expensive, is difficult to uncork, requires long decanting and does not keep after it's opened.

To meet the demands of the marketplace and modern lifestyles, producers are offering more consumer- and restaurant-friendly ports, which can be drunk younger, don't necessarily require decanting and can be re-corked for later consumption.

Signaling the new breed is Warre's Otima, a ten-year-old tawny, introduced by Symington Estates in 2000, that comes in a white bottle with a contemporary label. It is, says Paul Symington, Joint Managing Director of the long-time family-owned company, "a classic example of how a traditional wine such as port can rejuvenate its image." Otima follows another quality port that has successfully broken into the restaurant market—"late bottled vintage," a port left in barrels for four-to six years before bottling.

The port industry asserts that its wine has never been better. Private and European Union money has gone into modernizing the vineyards with new technology and machinery, including automated treading machines, although some human treading is still done.

These efforts might be paying off. Symington reports that revenues have increased 19 percent since 1992, and that premium ports (reserve ports, late bottled vintage ports, 10- and 20-year-old tawny ports and vintage ports) sold even more successfully, accounting for nearly 20 percent of all port sales.

Last year, however, world sales declined 2.2 percent. The United States is now the number two consumer of premium varieties and sixth of all ports. The biggest port drinkers are the French, who prefer white port as aperitifs, while the British are still first in vintage port consumption but rank fourth overall.

The irony in these figures is that port owes its existence to the historical conflicts between Britain and France. In the late 17th century, after yet another war cut the British off from their French claret, they turned to Portugal, and in 1703 were given preferential trade status. Brandy was added to red wine to stabilize it during shipment. Thus, port was born, and with it singularly British customs like the passing of port.

The host first serves the gentleman to his right, then himself and then passes the bottle to the man to his left, who does likewise until it returns to the host. Anyone failing to pass the bottle is asked by the host, "Do you know the Bishop of Norwich?" If the guest is clueless, the host says, "He's an awfully nice fellow, but he never remembers to pass the port."

But to port devotees, it isn't the tradition that matters, it's the wine.

"The sheer variety of flavors in, say, a 1927 vintage port, are only revealed after years of aging," says Tom Cave of the venerable London wine merchants Berry Bros & Rudd. "This is when the sum of all the components combine and the wine becomes more like a gas than a liquid, an ethereal experience, but one worth waiting for."

Dina Modianot-Fox is a regular Smithsonian.com contributor.