The Science of Champagne, the Bubbling Wine Created By Accident

There’s a lot more than meets the eye when it comes to the spirit’s trademark fizziness

![]()

Photo by Flickr user _FXL

A glass of champagne is often synonymous with toasting some of life’s biggest moments—a big promotion at work, weddings, the New Year. So too, is the tickle that revelers feel against their skin when they drink from long-stemmed flutes filled with bubbly.

There’s more to that fizz than just a pleasant sensation, though. Inside a freshly poured glass of champagne, or really any sparking wine, hundreds of bubbles are bursting every second. Tiny drops are ejected up to an inch above the surface with a powerful velocity of nearly 10 feet per second. They carry aromatic molecules up to our noses, foreshadowing the flavor to come.

In Uncorked: The Science of Champagne, recently revised and translated into English, physicist Gerard Liger-Belair explains the history, science and art of the wine. His book also features high-speed photography of champagne bubbles in action and stop-motion photography of the exact moment a cork pops (potentially at a speed of 31 miles per hour (!). Such technology allows Liger-Belair to pair the sommelier with the scientist. “Champagne making is indeed a three-century-old art, but it can obviously benefit from the latest advances in science,” he says.

Liger-Belair became interested in the science of bubbles while sipping a beer after his finals at Paris University about 20 years ago. The bubbles in champagne, he explains, are actually vehicles for the flavor and smell of champagne, elements that contribute to our overall sipping experience. They are also integral to the winemaking process, which produces carbon dioxide not once but twice. Stored away in a cool cellar, the champagne, which could be a blend of up to 40 different varietals, ferments slowly in the bottle. When the cork is popped, the carbon dioxide escapes in the form of Liger’s beloved bubbles. Once poured, bubbles form on several spots on the glass, detach and then rise toward the surface, where they burst, emitting a crackling sound and sending a stream of tiny droplets upward.

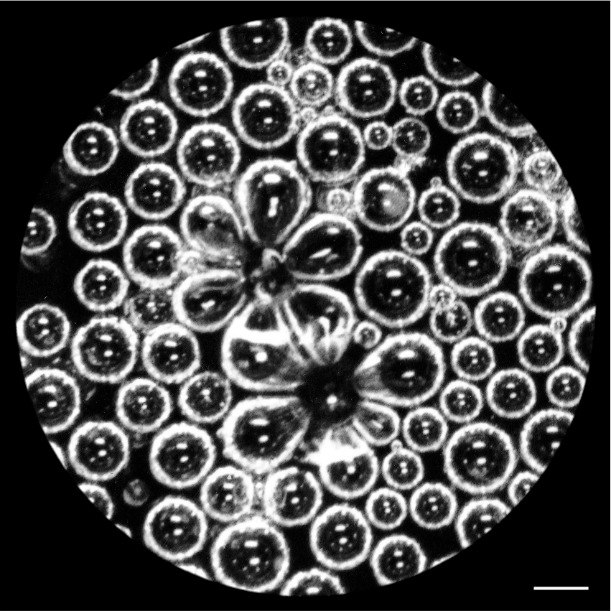

Bubbles that collapse next to each other create a flower-like pattern before disappearing. Photograph by Gérard Liger-Belair.

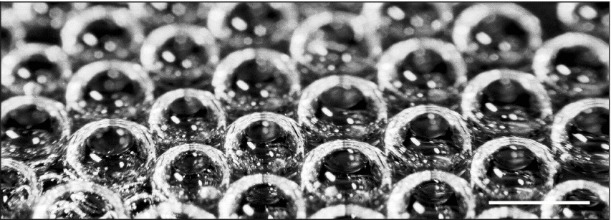

These bubble-forming hot spots launch about 30 bubbles per second. In beer, that rate is just 10 bubbles a second. But without this phenomenon, known as effervescence, champagne, beer and soda would all be flat.

Once the bubbles reach the top of the flute, the tension of the liquid below becomes too great as it pulls on them. The bubbles pop in a matter of microseconds. When they burst, they release enough energy to create tiny auditory shock waves; the fizzing sound is a chorus of individual bubbles bursting. By the time champagne goes flat, nearly 2 million bubbles have escaped from the glass.

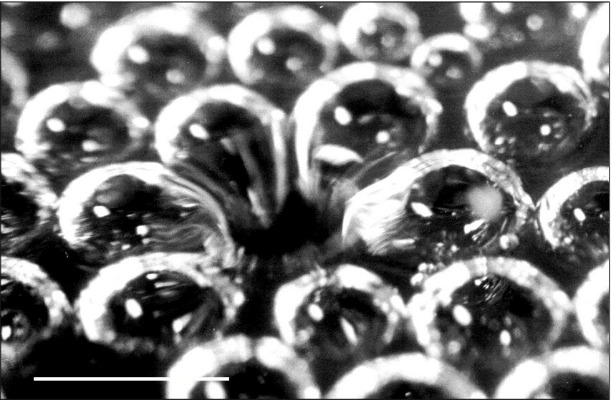

The collapse of bubbles at the surface is Liger-Belair’s favorite thing about champagne. “Bubbles collapsing close to each other produce unexpected lovely flower-shaped structures unfortunately completely invisible by the naked eye,” he says. “This is a fantastic example of the beauty hidden right under our nose.”

—–

Europeans, though, once considered the bubbling beverage a product of poor winemaking. In the late 1400s, temperatures plunged suddenly on the continent, freezing many of the continent’s lakes and rivers, including the Thames River and the canals of Venice. The monks of the Abbey of Hautvillers in Champagne, where high-altitude made it possible to grow top quality grapes, were already hard at work creating reds and whites. The cold temporarily halted fermentation, the process by which wine is made. When spring arrived with warmer temperatures, the budding spirits began to ferment again. This produced an excess of carbon dioxide inside wine bottles, giving the liquid inside a fizzy quality.

A closer look at a cluster of bubbles at the surface of a glass of champagne. Photograph by Gérard Liger-Belair.

In 1668, the Catholic Church called upon a monk by the name of Dom Pierre Pérignon to finally control the situation. The rebellious wine was so fizzy that bottles kept exploding in the cellar, and Dom Pérignon was tasked with staving off a second round of fermentation.

In time, however, tastes changed, starting with the Royal Court at Versailles. By the end of the 17th century, Dom Pérignon was asked to reverse everything he was doing and focus on making champagne even bubblier. Although historical records show that a British doctor developed a recipe for champagne six years before Pérignon began his work, Pérignon would come to be known as the father of champagne thanks to his blending techniques. The process he developed, known as the French Method, incorporated the weather-induced “oops” moment that first created champagne—and it’s how champagne is made today.

Bubbles at the surface of a freshly poured flute of champagne. Photograph by Gérard Liger-Belair.

So the next time you raise a glass of bubbly, take a second to appreciate its trademark tickle on another level—a molecular one.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/marina-koren-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/marina-koren-240.jpg)