Is There a Future For Instant Coffee?

Ask China, they’re buying the most of it

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/08/1c/081cbe49-1753-4cf6-9f4d-6997ece46cb8/42-27213618edit.jpg)

One would think that the heyday of instant coffee has long-since passed. Commercials for Folgers, Maxwell House or Nescafe are hard to come by and Starbucks’ VIA has yet to capture the market of the morning coffee addicts. But no one there is crying over spilled half-and-half. Also long-gone is the era when Starbucks was just a go-to local spot in downtown Seattle. Last year, though, Starbucks grossed $3.9 billion in global sales, a major force behind the mainstreaming of coffee connoisseurship. Nespresso, the capsule-based home brewing system owned by Nestle, which allows for a quick hit of espresso, has shown impressive growth and is investing more in the sphere. But whither instant coffee? Hardly.

In the past decade, the instant coffee market has actually expanded at rates of seven to 10 per cent a year, according to the Global Coffee Report; the International Coffee Organization projects a four percent global volume growth between 2012 and 2017.

But who is buying this stuff? China.

The country that historically drank about two cups of coffee per year per person is now the fourth-largest global market for ready to drink (RTD) coffee in terms of volume. The reason? Convenience. A 2012 poll found that 70 percent of Chinese workers said they were overworked and more than 40 percent stated they had less leisure time than previous years. Plus, most new buyers are used to boiling water to make tea, often owning just a teapot and not the appliances needed to make a fresh pot of coffee. By 2017, the Chinese RTD coffee market is projected to increase by 129 percent in volume.

Countries like China and non-coffee-producing, emerging markets like Russia are choosing instant as an affordable first step into the world of coffee. The RTD industry has seemingly come full circle, as the convenient caffeinator has its roots in Great Britain.

Like many food innovations, the origin of instant coffee has several claimants. According to Mark Pendergast in Andrew F. Smith’s indispensable The Oxford Companion to American Food and Drink, the first versions of the powdered drink dates back to 1771, about 200 years after coffee was introduced to Europe, when the British granted John Dring a patent for a “coffee compound.” In the late 19th century, a Glasgow firm invented Camp Coffee, a liquid “essence” made of water, sugar, 4 percent caffeine-free coffee essence, and 26 percent chicory. In the United States, the earliest experiments with instant coffee date back to the Civil War when soldiers sought out easy-to-carry energy boosts. But it wouldn’t be until the mid-to-late 1800s that a version of Camp Coffee would hit the retail market in the United Kingdom.

In post-war San Francisco, James Folger and his two sons opened a coffee company. Folger's, then spelled with the possessive ‘s’, sold the first canned, ground beans that Americans didn't have to roast and grind at home—a marketing tactic that was meant to entice miners during the Gold Rush for its convenience. The brand survived bankruptcy and in 1906 Folger's was the only coffee roaster to remain standing through the city’s devastating earthquake. Folger’s became one of the two most popular coffee brands in the country—right up there with Maxwell House which was founded by Kentucky native Joel Cheek in 1920. Neither of the brands would come out with instant coffee varieties until after WWII—they specialized in cheap, ground coffee bean blends—but they added a convenience to coffee-drinking that would pave the way for instant varieties ahead.

Until recently, the invention of the first commercial instant coffee was attributed to Tokyo chemist Sartori Kato who introduced his powdered coffee in Buffalo, New York, at the Pan-American Exposition in 1901. Later it was discovered that New Zealander, David Strang applied for a patent for his "soluble coffee powder" in 1890 under the name Strang's Coffee. Strang also filed patents for a "coffee-roasting apparatus of novel design" and Strang's Eclipse Hot Air Grain Dryer. He is also credited for making mocha—a blend of coffee and cocoa that’s now a standard coffee house offering a flavor that’s become ubiquitous.

By 1906, Cyrus Blanke introduced a new coffee powder to the market. As the story goes, Blanke came up with the idea while at lunch at the popular Tony Faust’s Cafe in St. Louis. When he spilled a drop of coffee onto a hot pie plate, the coffee dried up immediately leaving a dry, brown powder. He then realized that when water was added to the residue, it became coffee again. This moment, as the story goes, led to Faust Coffee, which Blanke named after the cafe.

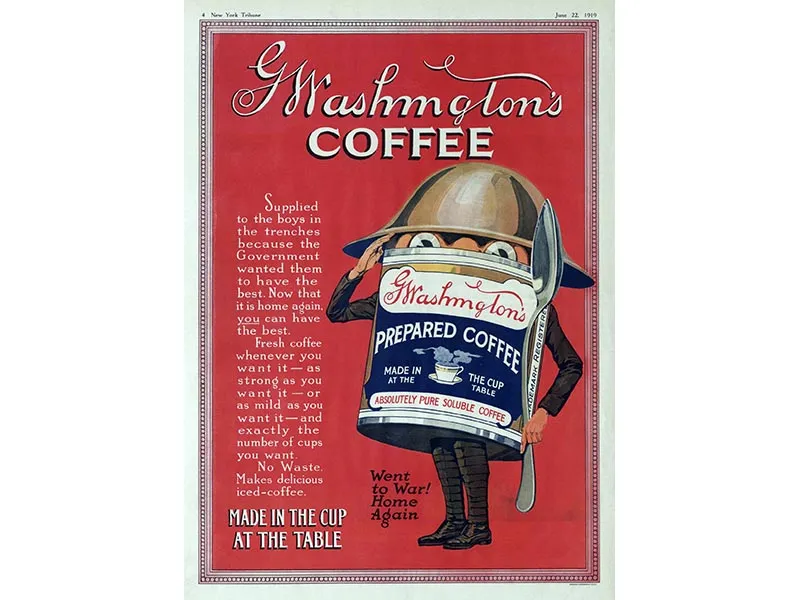

Four years later, European immigrant George Washington refined coffee crystals from brewed coffee to create the first commercially viable instant coffee in the United States, becoming popular during World War I for its convenience.

It wasn’t until 1938 that instant coffee technology changed or improved at all. That year, Nestle launched Nescafé by spraying coffee liquid into heated towers. What was left when rehydrated became coffee again. Nescafé is still one of the most popular instant coffee brands. In 2012, Nescafé accounted for 50 percent of the global Ready to Drink market (a mixture of coffee, milk and sugar) and 74 percent of the instant market.

In The Book of Coffee and Tea, author Joel Schapira cites "Instants: Quality vs. Cost," originally published in World Coffee and Tea, regarding the changes in instant coffee technology in the early ’40s. Instant coffee at the time was "typically a fine light-colored powder, usually containing as much as 50 percent of added carbohydrates to bulk the product in the jar and in the teaspoon,” the article states. It wasn’t until the ’50s that a more sophisticated dehydration technique was developed where larger particles of instant coffee could be produced, meaning the final product could stretch a long way without the added carbohydrates. There was still something missing though: the wonderful aroma of freshly ground coffee beans.

In the ’60s producers added oils from coffee beans as an afterthought to include the aroma of fresh coffee. When customers opened the jar, the smell of coffee escaped, but as soon as the substance was mixed with water or milk, the aroma disappeared. Not only that, the added oils introduced the threat of rancidity to the product which wasn’t remedied until the mid sixties.

Perhaps the biggest innovation in instant coffee technology came in 1964 with freeze-dried coffee—it maintained the flavor and smell of fresh coffee without the added oils.

The late ’60s introduced the technique of aglomeration in which particles of instant coffee were steamed and made sticky so they would lump together, Schapira says. The lumps were then redried via reheating so they looked more like ground coffee. The only catch was that reheating the particles compromised some of the richness in flavor. This was solely for improved aesthetics of the product and remained a marketing strategy until the process of freeze-drying was developed during WWII.

Freeze-drying changed the mass production of instant coffee because the finished product looked more like ground coffee and tasted better. Though the process was more expensive than spray drying—a type of aglomeration—it didn’t expose the granules to a stream a hot air.

By 1989, instant coffee saw the beginning of a major decline in sales. As fresh-brewed coffees and cafes grew in popularity, it seemed there was no room for the tasteless (though more convenient) option. Big companies like Maxwell House, one of the first brands to offer instant coffee in the U.S., made huge cutbacks as sales plummeted. In 1990's Nestle’s Taster's Choice hit shelves offering “gourmet” instant coffee, but it couldn’t compensate for Americans’ increasing preference for a freshly-brewed cup of joe.

That didn’t stop Starbucks from launching its VIA product in September 2009, marketed for its “microground” technology. President-CEO Howard Schultz predicted the product would “change the way people drink coffee,” but it hasn’t taken over the market for gourmet, fresh-brewed coffee—Americans still prefer fresh coffee to instant. The packets of “coffee in an instant” that now come in many flavors and mixtures, sold $180 million globally in the first two years, Reuters reports. It has since trickled down in popularity—currently taking fifth place in instant coffee sales by brand volume in the U.S., according to Euromonitor International.

But overseas, instant coffee is tapping into a new market: tea drinkers. As of 2013 in Great Britain, tea bag sales dropped 17.3 percent while sales of Nescafé instant coffee went up in supermarkets by more than 6.3 percent. The country known for it’s tea and crumpets may be making a similar transition to China’s tea-drinking population.

Like in Britain, sales of the internationally successful Nescafé increased in Morocco last year according to Euromonitor International. The majority of buyers included mid-and high-income teens and young adults in urban areas. American teens by contrast, really love a Starbucks Frappuccino.

Last year, India's largest coffee producer, Tata Coffee, opened a premium coffee extraction plant in Tamil Nadu to better focus on it's freeze-dried and agglomerated instant coffee sales. In India and countries including Portugal and Spain, instant coffee is often whipped with milk and sugar.

But it will take a lot more than a fancy Starbucks product to convince Americans to drink products like this one sold in China—instant coffee with jelly.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/561436_10152738164035607_251004960_n.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/561436_10152738164035607_251004960_n.jpg)