I wish I could tell you that the “blood” in Blood Bros BBQ was literal. That sometime in the mid-1980s, three Asian-American friends in suburban Houston met under the bleachers of their high school football stadium and performed some kind of ritual with a drawn blade in which they swore eternal fealty in smoke and flesh. Sadly, no knife, no blood.

This is a different kind of tale: a great American story about the great American food. The brother part is real, anyway. Terry Wong and his younger-by-18-months sibling, Robin, make up two-thirds of the Blood Bros, whose year-old restaurant has made waves in the world of Texas barbecue. The third, honorary Bro is Quy Hoang, who has the distinction of being the first Vietnamese-American to work as a pit master in Houston, a city with no shortage of either.

Blood Bros BBQ is located in a strip mall in the Houston suburb of Bellaire. The location should come as no surprise: After years of the so-called Great Inversion—in which affluent professionals flocked back to city centers, leaving the suburbs to recently arrived immigrants—we should all be accustomed to finding the most exciting developments in food happening amid pawnshops and nail salons and urgent care centers.

Blood Bros occupies a storefront that was most recently a Smoothie King. The Bros spent $400,000, mostly borrowed from family and friends, and transformed it into a shining example of the modern barbecue aesthetic: No grinning pigs eating each other or themselves. No faux-Southern signage. No groan-inducing puns. Just a cool rectangular space with smooth wooden banquettes (built by the Wongs’ stepfather) and warmly glowing orange walls.

But the visual centerpiece of the space is on the wall behind the bar. It’s a mural, painted by the local artist Daniel Quinones, with graffiti-style letters at its center spelling “Alief.” The Blood Bros grew up in that suburb (pronounced A-leaf) 15 miles southwest of Houston, going to schools where the kids spoke as many as 70 different languages. In spite of all that diversity—or because of it—Alief has a fiercely unifying sense of hometown pride. “You’ll meet somebody you really get along with and then find out they’re from Alief,” says Hoang, “and it’s like, ‘Oh yeah, now it makes sense.’”

One Monday, when the restaurant is closed, we pile into Hoang’s 2006 Dodge Charger, whose color is strikingly similar to the restaurant’s walls. The partners are all wearing Blood Bros baseball caps, in different combinations of colors. Black and white for Hoang, 46, who is wiry, heavily tattooed and wearing dark-rimmed glasses. Black with orange for Robin, 44, the younger and more serious Wong. Sky blue for Terry, also 46, who is big and genial, with a sleepy expression exacerbated by the prosthetic he wears after losing his right eye to a mysterious infection a little over a year ago. The hat complements the design on Terry’s shirt, an oil derrick made up of the letters FYHA, short for “ F--- You, Houston’s Awesome.”

The car sails down the Westpark Tollway, rumbling like a single-engine plane. Soon a water tower painted with the name Alief comes into view. “All this was still fields when we were kids,” says Terry.

The story of Alief is in many ways the story of modern Houston. Founded in 1895, Alief remained a sleepy town of rice farms, gravel roads and largely German immigrants deep into the 20th century. That changed in a hurry starting in the early 1970s, as Houston’s population began to spread beyond the city limits. By the 1980s, the population of Alief had swelled to over 130,000. It had also been transformed from majority white to a kaleidoscope of black, Hispanic and Asian communities.

The physical manifestation of all that growth awaits as we pull off the highway: a sprawling high school campus as large as many community colleges. There are, in fact, two high schools across the street from each other, each large enough to include several different wings. They share a stadium that looks newer and flashier than some professional arenas. “You’re in Texas, man,” says Terry. “We take football serious.”

Hoang and the Wongs attended Elsik High, rather than its cross-street rival, Hastings, but effectively the two schools formed one massive crucible of youthful energy. “You can imagine what it was like at 3:30 p.m. every afternoon when the bell rang and 8,000 kids spilled out onto the street,” Hoang says.

The Blood Bros met in the midst of that scrum. Hoang was born in Vietnam and came with his parents to the States at 18 months old, making stops in Louisiana and Maryland before settling in Texas. The Wongs are third-generation Chinese-Americans whose grandfather immigrated from Guangzhou in 1926, stopping in Birmingham, Alabama, and Knoxville, Tennessee, where he opened a laundry, before making his way to Houston in the early 1960s. As boys, the Bros bonded over skateboards and bikes, hip-hop and a shared love of the camp classic Big Trouble in Little China. (“Pork Chop Express,” the name of Kurt Russell’s truck in that film, was an early contender for the name of their barbecue restaurant; Hoang has the truck’s logo tattooed on his forearm.)

The friends drifted apart after high school. Hoang joined his uncle in a business selling and maintaining high-end aquariums. The Wongs opened Glitter Karaoke, a bar in Chinatown that became a cultural meeting point. “Back then, Cantonese karaoke places would only do Chinese karaoke. Vietnamese places would only do Vietnamese. American would only do American,” says Robin. “We’re ABC”—American Born Chinese—“so we could enjoy all of it.”

In 2010, the brothers decided to move Glitter to Midtown, where it quickly became a favorite after-hours hangout for Houston’s chefs. By then, the Wongs had reconnected with Hoang, who had developed a reputation as a stellar home griller. He began hosting pop-ups outside Glitter and experimenting with barbecue techniques. Eventually one of the Wongs heard about an old barrel smoker for sale for $1,500. They offered to split the cost with Hoang, to see what he came up with. “And that was it,” says Robin. “If we hadn’t bought that smoker, who knows what we’d be doing.”

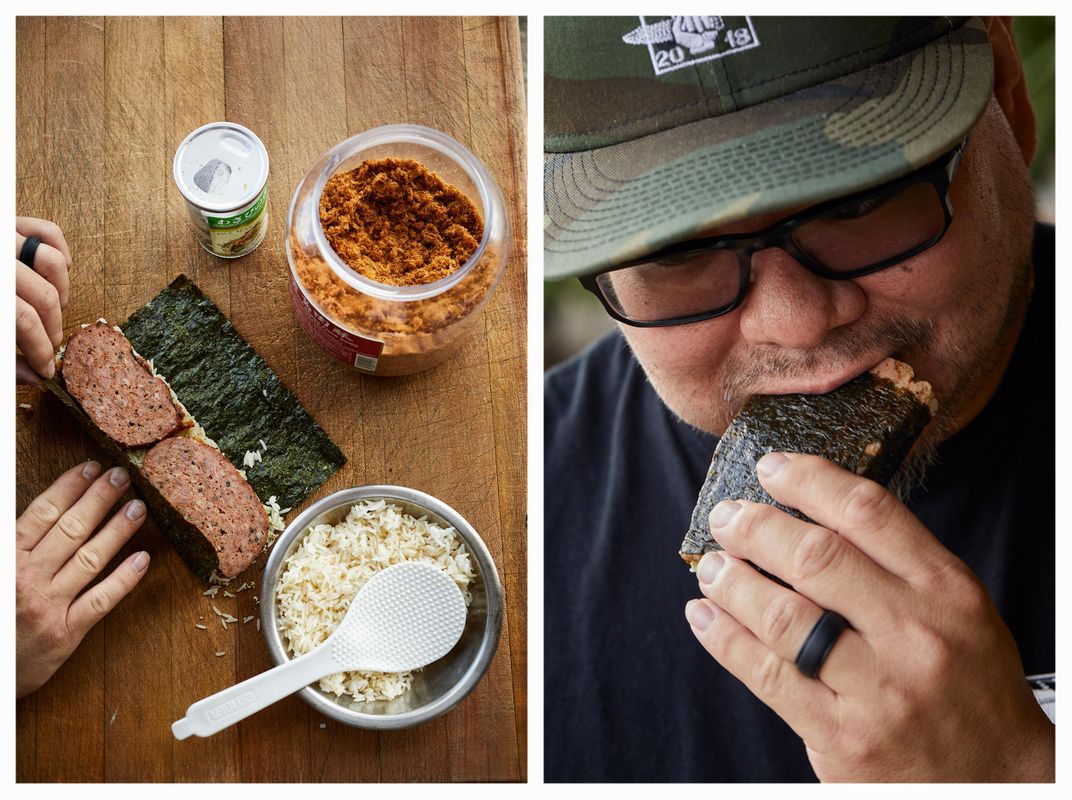

Hoang proved a quick study with the classic items known as the Texas Trinity. That’s brisket, sausage and ribs, though the term implies an equality that doesn’t exist: Brisket is forever king. He also started experimenting with creations like beef belly burnt ends glazed with Korean gochujang chili paste and ricey links of boudin sausage laced with Thai curry. In Houstonia magazine, J.C. Reid, who would go on to be the Houston Chronicle’s barbecue columnist (a real job), praised “Hoang’s creativity, which isn’t hampered by preconceived notions of what barbecue should be.” After several years, the men thought about turning their hobby into a real business.

It’s a common narrative in barbecue, this passage from amateurism to entrepreneurship. Barbecue is a deep craft, but a narrow one. The barriers to entry are low; the equipment and ingredients relatively inexpensive. Given sufficient obsession and effort, excellence is within reach.

Also, the Blood Bros quickly learned, nearly everybody likes to eat it.

* * *

Blood Bros opened its brick-and-mortar doors last December, on a morning when the temperature may have read in the high 50s, but the damp Gulf wind whipping across the Bellaire parking lot made it feel much colder. By 10 a.m., an hour before opening, there was already a small band of hungry barbecue hounds taking shelter in the recessed entryway. Those who arrived after that had no such

recourse, as the line stretched out along the sidewalk.

Lining up in inclement weather is part of barbecue culture, though more often the inclemency is of the blazingly hot variety—which forges a kind of bond with the pit masters, holding their lonely vigil over the flames. The line at Franklin Barbeque in Austin, ground zero of the modern barbecue boom, is legendary, a veritable tailgate party that has become as much a part of the experience as the transcendent brisket that is its ostensible goal.

You line up because scarcity is built into the barbecue equation: A pit master can only produce so much each day without compromising quality. A closing time at a barbecue joint is a bad sign. The magic words instead are “Until Sold Out.” That December day, Blood Bros was out of food by 1:30 p.m., and its daily close has hovered at 2:30 p.m., at the latest, ever since. Daniel Vaughn, the barbecue editor of Texas Monthly (also a real job), recently named Blood Bros to his quadrennial list of Top 25 New Barbeque Joints in Texas, which, along with his overall Top 50, has become a kind of Way of the Pilgrim for serious barbecue fans.

“For three bozos who know nothing about running a restaurant, we’re doing pretty well,” says Hoang.

The question of what makes great barbecue is controversial and territorial, with styles of sauce and preparation differing wildly from, say, eastern North Carolina to western North Carolina, let alone from state to state. What we think of as Texas barbecue is a product of Central Texas. When Franklin Barbeque opened in 2009, it ushered in an era of “urban barbecue,” bringing chef-driven creativity and nerdy science to what had generally been a rough-hewn folk tradition. In the decade since, Texas barbecue has become the dominant style from Minneapolis to Minsk.

Houston may be only a few hours down the road from Austin, but it too received the modern Central Texas style as an outside influence. Indeed, J.C. Reid says, the city was slow to adopt it, largely because Houstonians are passionate about their own, porkier, saucier and largely African-American barbecue tradition. A year or so ago, Reid took me on a tour of Space City’s smoky evolution. We began at Ray’s Real Pit BBQ Shack, in the historically black Third Ward—meaty pork ribs; links of boudin stuffed with pepper-laden rice; sticky, gelatinous smoked oxtails. From there, it was on to the Pit Room, where brisket tacos came with smoked meat piled high atop soft, irregular-shaped flour tortillas made with rendered beef fat. Then, 90 minutes north to the rural-feeling suburb of Tomball to visit Tejas Chocolate+Barbecue, where we shared a massive beef rib encrusted in a sheath of pastrami peppercorns and spice. Tejas was co-founded by Scott Moore, a fifth-generation Texan who once sold parts for freight trains and taught himself barbecue because it seemed, quite reasonably, like a better way to spend one’s days.

“I am a Google graduate,” he said proudly, an explanation echoed almost word for word when I later asked Kaiser Lashkari, the Pakistani-born chef and owner of the legendary restaurant Himalaya, in Houston’s Mahatma Gandhi District, how he learned to make his brisket, which arrived under a blanket of thick, rust-hued and fragrant tikka masala.

All of this is to say that the Blood Bros’ journey, and their expansion of the classic barbecue menu, is entirely in keeping with the cuisine’s recent trajectory. In some instances—as with the Mexican-inspired rise of smoked meat tacos—the outside influences have already grown so commonplace as to be nearly invisible.

* * *

On our tour of Alief, we stopped in a Vietnamese restaurant that had once been a high school hangout for the Blood Bros. Hoang ordered in Vietnamese, and the table soon filled with steaming dishes. One was banh bot chien, a plate-sized omelet topped with crispy rice cakes and fried scallions and a thin, pungent soy sauce.

“We should do a special like this,” said Terry.

“We could smoke the egg. Make it like a quiche,” said Hoang.

“Or like a pizza,” added Robin.

“Something to experiment with,” said Hoang, almost to himself. “Always an experiment...”

Still, it’s notable that on Blood Bros’ opening day last December, its menu was all but indistinguishable from that of any other modern Texas barbecue joint. The Bros say that was a deliberate decision. “We didn’t want to get niched,” Hoang explains. “We don’t want it to be ‘Oh, those are the Asian guys.’ We wanted to do the Trinity so well that nobody could say anything about it.”

It’s a debate among the three: Just how “Asian” do they want their barbecue to be? The Bros’ breakthroughs have been a source of great pride in the Vietnamese and Chinese communities. They have been asked to cater an annual gathering for the Asian Pacific American Advocates, an influential national organization. Customers routinely ask for selfies and autographs.

On a practical level, too, one thing about the barbecue boom is that it has produced an awful lot of barbecue—three other restaurants within two blocks of Blood Bros, just for starters. Pit masters of every ethnicity and background must always be on the lookout for variations that will make them stand out in a crowded field.

Still, Robin says, “We don’t want to be a novelty.” They have added their distinctively Asian items slowly. A sensational Vietnamese banh mi—stuffed with pickled vegetables, chicken liver pâté and Hoang’s smoked turkey breast. That loamy, tingling Thai green curry boudin, which is a profound tribute to both Southeast Asia and Cajun Country. A frequent special of fried rice made with leftover nuggets of smoky brisket. “It’s not really Chinese. It’s not Vietnamese. It’s just fried rice,” says Robin.

Customers often approach the Blood Bros, boasting that they can detect lemongrass or Sichuan peppercorn or Chinese five-spice powder in Hoang’s barbecue rub. (It consists simply of salt, pepper and cayenne.) Or they’ll swear up and down that there is sriracha in the house barbecue sauce. (There isn’t.) “I’m like, ‘I don’t know what’s going on with your palate, but there’s none of that in there,’” says Robin. “What you’re tasting is your preconceived notions.”

And what could be more American, after all, than all of these negotiations—between what makes you the same and what sets you apart, between what your community expects and what your heart desires, between the self of your birth and the self of the world you grew up in. Barbecue, to say it again, is great American food. It is also great immigrant food. But of course, that is exactly the same thing.

:focal(1488x923:1489x924)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/75/09/7509bb4d-3cac-4809-a3f6-1aa8399a6d77/1_nov2019_b04_asianbbq.jpg)