When Heineken Bottles Were Square

In 1963, Alfred Heineken created a beer bottle that could also function as a brick to build houses in impoverished countries.

There are plenty of examples of structures built from recycled materials—even Buddhist temples have been made from them. In Sima Valley, California, an entire village known as Grandma Prisbey’s Bottle Village was constructed from reused glass. But this is no new concept—back in 1960, executives at the Heineken brewery drew up a plan for a “brick that holds beer,” a rectangular beer bottle that could also be used to build homes.

Gerard Adriaan Heineken acquired the “Haystack” brewery in 1864 in Amsterdam, marking the formal beginning of the eponymous brand that is now one of the most successful international breweries. Since the first beer consignment was delivered to the United States upon the repeal of Prohibition in 1933, it has been a top seller in the United States. The distinctive, bright green of a Heineken beer bottle can be found in more than 70 countries today. The founder’s grandson, Alfred Heineken, began his career with the company in 1942 and was later elected Chairman of the Executive Board at Heineken International. Alfred, better known as “Freddy,”oversaw the design of the classic red-starred label released in 1964. He had a good eye for marketing and design.”Had I not been a beer brewer I would have become an advertising man,” he once said. When Freddy’s beer took off in the international market, he made it a point to visit the plants the company had opened as a part of its globalization strategy.

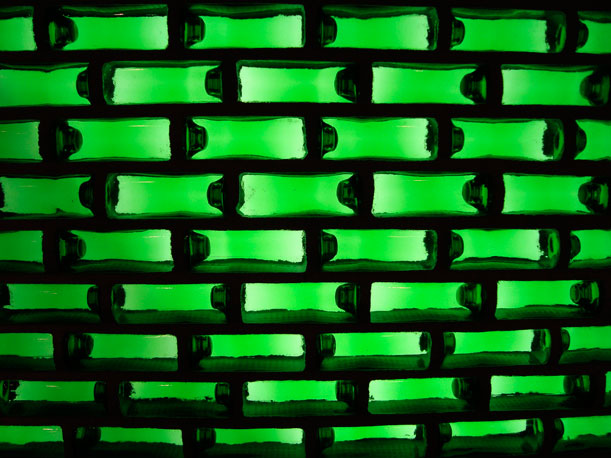

A display of WOBO “bricks” from the Heineken Experience, in Amsterdam. Image courtesy of Flickr user seaotter22.

In 1960, Freddy took a trip to the island of Curacao in the Caribbean Sea and discovered that he could barely walk 15 feet on the beach without stepping on a littered Heineken bottle. He was alarmed by two things: First, the incredible amount of waste that his product was creating due to the region’s lack of infrastructure to collect the bottles for reuse. (Back then, bottles were commonly returned for refilling, lasting about 30 trips back and forth to the breweries). Second, the dearth of proper building materials available to those living in the impoverished communities he visited. So he thought up an idea that might solve both of these problems: A brick that holds beer.

The rectangular, Heineken World Bottle or WOBO, designed with the help of architect John Habraken, would serve as a drinking vessel as well as a brick once the contents were consumed. The long side of the bottle would have interlocking grooved surfaces so that the glass bricks, once laid on their side, could be stacked easily with mortar or cement. A 10-foot-by-10-foot shack would take approximately 1,000 bottles (and a lot of beer consumption) to build. Yu Ren Guang explains in Packaging Prototypes 3: Thinking Green:

“On returning to Holland , Alfred set about conceiving the first ever bottle designed specifically for secondary use as a building component, thereby turning the function of packaging on its head. By this philosophy, Alfred Heineken saw his beer as a useful product to fill a brick with while being shipped overseas. It became more a case of redesigning the brick than the bottle.”

A handful of designers have accepted Alfred’s WOBO as one of the first eco-conscious consumer designs out there. Martin Pawley, for example, writes in Garbage Housing, that the bottle was “the first mass production container ever designed from the outset for secondary use as a building component.”

A WOBO wall. Image courtesy of Flickr user greezer.ch.

There were many variations of the original prototype—all of which were ultimately rejected as many components were considered unworkable. For example, a usable beer bottle needs a neck from which to pour the beer and a protruding neck makes it harder to stack the product once the beer’s run out—problematic for brick laying. The finalized design came in two sizes—350 and 500 milimeters (35 and 50 centimeters)—the smaller of which acted as half-bricks to even out rows during construction. In 1963, the company made 50,000 WOBOs for commercial use.

Both designs (one of the wooden prototypes is pictured in Nigel Whiteley’s Design for Society), were ultimately rejected by the Heineken company. The first prototype for example, was described by the Heineken marketing team as too “effeminate” as the bottle lacked ‘approprate’ connotations of masculinity. A puzzling description, Cabinet writes, “considering that the bottle consisted of two bulbous compartments surmounted by a long shaft.”

For the second model, Habraken and Heineken had to thicken the glass because it was meant to be laid horizontally—a costly decision for an already progressive concept. The established cylindrical designs were more cost effective and could be produced faster than the proposed brick design. But what most likely worked against Habraken’s design was that customers simply liked the easy-to-hold, cylindrical bottle.

Though the brick bottles never saw the market, in 1965 a prototype glass house was built near Alfred Heineken’s villa in Noordwijk, outside Amsterdam. Even the plastic shipping pallets intended for the product were reused as sheet roofing. The two buildings still stand at the company’s former brewery-turned-museum, The Heineken Experience.

A Heineken label circa 1931. Image courtesy of Heineken International.

Where Heineken failed in creating a reusable brick bottle, the company EM1UM succeeded. The bottles, which were easier to manufacture for most automatic bottling machines than Heineken’s design, were made to attach lengthways or sideways by pushing the knobs of one into the depressions of another. EM1UM was mostly successful in Argentina and collected awards for bottle designs including prisms, cubes and cylinders.

In 2008, French design company, Petit Romain, made plans to make its own take on Alfred Heineken’s WOBO design, the Heineken Cube. It’s similar to the original concept in that it’s stackable, packable and altogether better for travel than the usual, clinky, cylindrical bottles. The major difference is that the cube is meant to save space, not to build homes. Like Freddy’s WOBO, the Cube is still in the prototype stage.

Though Freddy’s brick design never took off, it didn’t stop Heineken International from maintaining the lead in the global brew market. By ’68, Heineken merged with its biggest competitor, Amstel. By ’75 Freddy was one of the richest men in Europe.

A fun, slightly-related fact: Alfred Heineken and his chauffeur were kidnapped in 1983 and held at a 10 million dollar ransom in a warehouse for three weeks. Lucky for Freddy, one of the kidnappers gave away their location mistakenly while calling for some Chinese takeout. According to the Guardian, after the incident, Heineken required at least two bodyguards to travel with him at all times.

Alfred played a large role in the company’s expansion, championing a series of successful acquisitions, right up until his death in 2002. While his plans for translucent, green bottle homes never came to fruition commercially, the Wat Pa Maha Chedi Kaew temple, constructed from a mix of one million bottles from Heineken and the local Chang beer remains proof of the design’s artfulness. For some designers, it seems, there is no such thing as garbage.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/561436_10152738164035607_251004960_n.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/561436_10152738164035607_251004960_n.jpg)